Air Cargo and Bangladesh’s Export Trade

By

After a two-year suspension of direct Dhaka–London air cargo flights, the UK government has lifted the ban on airfreight, following strenuous efforts made by the Bangladesh authorities to improve standards of aviation security at Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport (HSIA).

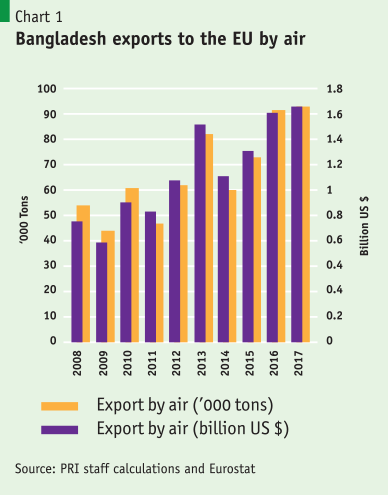

The cargo industry makes a significant contribution to the export–import community of the country, but over the years it has seen its ups and downs. The year 2016 in particular proved a turbulent period for the airfreight industry of Bangladesh. Following Australia and the UK, Germany became the third country to restrict direct cargo flights from Bangladesh, finding safety and security measures to be insufficient. A somewhat common security requirement while sending air cargo is screening the goods using bomb detection equipment before they are loaded onto the aircraft. Regrettably, none of this equipment was available at HSIA, one of the three international airports in Bangladesh and a hub for air cargo. Soon after the ban was imposed, German carrier Lufthansa was forced to leave up to 60 tons of garments in Dhaka, which gives a hint of the damage done to the industry. Exacerbating the situation, in early June 2017 the EU declared HSIA a ‘red zone’. This came as a major setback to textile exporters as the EU was responsible for over $15 billion worth of textile exports in the given year alone. With over 92,000 tons of cargo carried by air every year to the euro region, this news was extremely concerning (Chart 1).

Despite prior warnings, Bangladesh was slow to respond to address the concerns raised. Following the consecutive bans, a British company, Redline Aviation Security Ltd, was given the responsibility of improving the system and training local staff. However, progress on advancing security at HSIA remained sub-par, which consequently started compromising the country’s export competitiveness.

The economics of air cargo

In the face of significantly higher costs, the real question is, why are traders constantly resorting to airfreight services for their international shipping needs?

Choosing the right mode of shipment can indeed be tricky. Today, air cargo accounts for less than 1% of world trade tonnage, and yet 35% of the world’s trade value is carried by air (Boeing World Air Cargo Forecast 2016–2017). While weight limitations, higher carbon emissions and a significantly hefty price tag place air cargo below sea transport, air cargo is critical to serve markets that demand speed and reliability for the transport of goods. High-value commodities such as electronic consumer goods, machinery, computing equipment, documents, pharmaceuticals and textiles account for the highest share of airborne trade tonnage versus its waterway counterparts. Seasonal shipments and products with shorter shelf lives – namely, cut flowers, fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, etc. – also make regular use of airfreight services. It is therefore safe to say that the use of airborne trade tonnage certainly has its own competitive advantages over containership tonnage.

Another major motivating factor for many traders is the issue of safety and security. Certain sensitive goods, such as medicines, drugs and documents that cannot travel any other way, must resort to airfreight facilities. Airfreight also allows exporters to track the status of their shipment at all times while it is in the air, thus making it more convenient for them if they have to deal with unexpected situations. In addition, the layover time for a cargo aircraft is very little. It can be as little as a few hours, unlike the layover time needed for shipping by sea: loading, unloading and inspection may take several days. The quicker transit time also means there is less need for local warehousing and stockpiling.

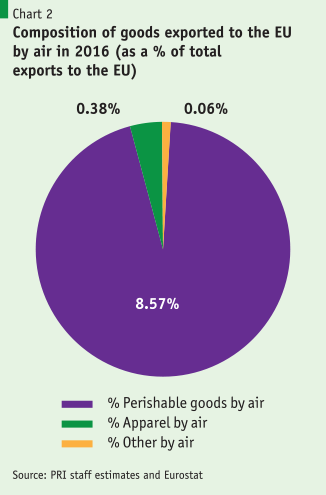

Accessibility is another major factor in demand for air cargo. Many countries are landlocked and do not have access to direct shipping. Although Bangladesh does not fall into this category, the use of airfreight has nevertheless been a priority. As surprising as it might seem, garment items form the bulk of the total quantity shipped by air in a year by Bangladesh to the EU. Nearly 85,000 tons of apparel items were shipped by air to the EU 28 in 2016, which made up approximately 95% of the total airfreight sent from Bangladesh to the EU and 8.6% of the country’s total exports to the EU (Chart 2). This highlights the severity of the problem incurred by the ban described above.

Many renowned companies identify meeting strict deadlines as the primary reason for using airfreight services. While under normal circumstances a significant proportion of all cargo is transferred by sea, production delays, climate factors and inefficient handling at ports may all result in the bulk movement of goods through airfreight. Recently, many factories in Dhaka faced production delays as a result of a disrupted gas supply. As sea shipments take approximately 30–40 days to reach their destination, many textile companies had to resort to airfreight services as a faster alternative to ensure a timely delivery. In October 2017, Bangladesh sent a shipment of more than 70,000 tons of apparel by air to the EU. This clearly highlights the importance of air cargo to the country’s apparel exporters in the face of emergencies and production delays.

The cost impact of the ban

Despite their significantly higher cost, Bangladesh has been a leader in the region in terms of its use of airfreight services to the EU. While water shipment of goods to any European country generally costs around $800 or more for a 20 foot container, airfreight tends to cost more than $30,000 to the same destination (for a payload of 17,000 kg or above). However, the difference in cost depends heavily on the cargo shipped. As airplane capacity is typically limited by weight, the difference in price for sea freight and airfreight is less for light cargo than it is for heavy cargo.

According to local sources and data published by Freightos, a 27 cbm crate travelling by air (the cubic capacity of a 20 foot container) is typically priced 11 to more than 20 times that of a crate using sea transport, making it an immensely expensive mode of carriage. This is not to mention the fact that the payload capacity of sea shipment will be much higher than that of the air counterpart, allowing it to carry more kilograms of goods for the same cubic capacity at a lower rate.

Following the latest EU decision, the cost difference further increased, adding to the already inflated cost of export by air. Re-screening cargo, sent from HSIA, at a third country airport resulted in an approximate increase in the air cargo cost of up to $2 per kg. FedEx also announced an additional re-screening charge of $0.15 per kg on shipments heading from Bangladesh to any European country. With an increase in the air shipment of apparel to the EU from over 66 million kg in 2016 to over 85 million kg in 2017, the additional cost of using airfreight to export to the EU would be approximately $19 million or above. Thus, on top of the already hiked cost incurred on the air shipment of 88 million kg in 2017, exporters also had to pay an additional surcharge of millions of dollars for third country screening. In 2017, however, the supplementary cost of third country screening was comparatively lower than that of 2016. This was primarily the result of the significantly smaller flow of air shipment of apparel recorded in that year (approximately 3 million kg in 2017 compared with 19 million recorded in 2016). Despite the smaller flow, the year witnessed at least $3 million of surcharge, considering that the increase in cost was a minimum of $1 per kg. The ban therefore adds significantly to the airfreight cost, thus compromising the country’s export competitiveness.

With an increase in the air shipment of apparel to the EU from over 66 million kg in 2016 to over 85 million kg in 2017, the additional cost of using airfreight to export to the EU would be approximately $19 million or above.

The cargo business of Bangladesh Biman has been a victim of the situation. In fiscal year 2016/17, the state-run carrier earned Tk 2.44 billion from its cargo business, in contrast with Tk 3.15 billion a year earlier. This points to the damage created by the ban. The situation could easily have been avoided had there been no security concerns regarding direct cargo flights from HSIA. In addition to the increased cost of third-party inspection, the cargo transit time also lengthened by a number of days, as a result of the added security checks and the re-routing of the cargo.

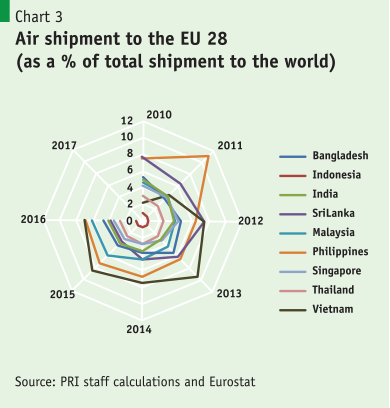

Irrespective of the increasing cost, Bangladesh’s exports to the EU by air were relatively higher than those of India, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Thailand in 2016. What is surprising is that the use of airfreight has in fact been increasing in the past few years for the country, with apparel dominating the bulk. In 2016, almost 4.7% (Chart 3) of Bangladesh’s total exports were composed of air shipments to the EU. Despite the ban and consequently the rising cost, there was an 0.5% increase in the use of airfreight in contrast with the previous year. This clearly highlights the increasing demand for airfreight services by the apparel exporters of the country.

However, Vietnam has been a leader in Asia in total airfreight exports to the EU since 2012, although this is not mainly for apparels. The country has been highly dependent on airfreight use for the export of computers, electronic products and components to the EU. In 2016, approximately 70% of Vietnam’s air shipments to the EU comprised electronic machinery and equipment. Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines were the only countries using airfreight services to the EU more than Bangladesh among the nations in Figure 3.

Policy issues

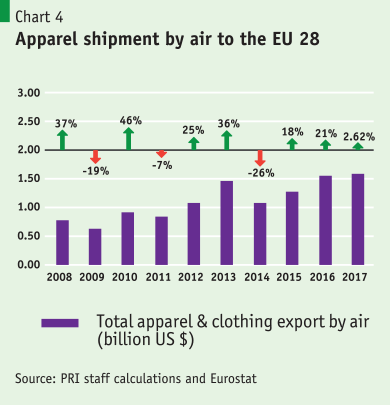

It is therefore quite evident that apparel and clothing accessories exports by air is on the rise for Bangladesh. Growth of 21% was recorded in 2016, compared with 18% in 2015 (Chart 4). This in a way also shows desperate attempts by exporters to meet delivery deadlines even in the face of higher transport costs that consequently affect their competitiveness. As long as security concerns at HSIA persist, costs will further pile up. Any issue in the domestic market – namely, gas or electricity supply issues, etc. – that increases the dependence of exporters on airfreight must therefore be identified and addressed. Given a situation where the dependence on airfreight cannot be curtailed, the concerned authorities should at least take the necessary steps to minimise the cost. While the neighbouring countries of India and Sri Lanka have already installed Morpho Explosives Detection Systems and Smiths Detection screening technology, respectively, it is astounding that a trade-focused country like Bangladesh lacked explosive tracking devices and other security measures before the issues were raised.

The good news is that, after years of dysfunctional security systems at HSIA, the alarms have finally had an effect. Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport has recently been equipped and upgraded with Explosives Detection System (EDS) and Explosive Trace Detector (ETD) machines to comply with the security standards of the EU and the UK. In addition, 37 dual-view X-ray machines have been installed at the airport and officials have received European standard training in cargo handling and operating the machines. Once the machines come into operation, it is believed that this will strengthen security features at the airport and ensure safe passage of passengers and goods throughout the world.

Although the UK has lifted the temporary suspension following significant progress made in meeting a number of important security conditions, the ban is still active on Bangladesh Biman, which needs to acquire the EU’s third-country regulated agent certification before it is allowed to offer cargo services to the UK again. Bangladesh will now have to undergo three joint safety assessments in a year for uninterrupted flights between Dhaka and London. The concerned authorities expect that, with time, Australia and the EU will restore trust in the security features at the airport and resume direct cargo transportation through HSIA. This will be a strong short-term measure in terms of addressing the increasing cost of air cargo. However, the task of strengthening export competitiveness by entirely mitigating the issues that would make unnecessary use of air cargo avoidable in the first place will remain a challenge.