Insights from the Latest Round of Poverty Data

By

We usually have to wait about five years at a time in assessing progress on poverty reduction in Bangladesh. Information for use in poverty evaluation is contained in the Household Income Expenditure Survey (HIES). Preliminarily results of the HIES 2016 were published in October 2017 – more than six years after the previous HIES, which was conducted in 2010. And yet, although there is general consensus on the need to shorten the intervals between the HIES rounds, this interval actually widened by more than a year in the latest case. This may have been a result of improvements in the methodology and wider coverage in 2016 compared with in 2010. For the first time, in 2016, quarterly data was collected in place of annual information, with the aim of releasing quarterly poverty estimates to highlight seasonal factors. Moreover, coverage in 2016 was almost four times that in 2010 (i.e. 46,076 households compared with 12,240 households).

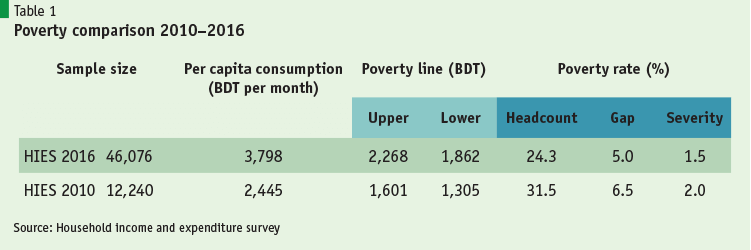

Two poverty lines based on basic needs (the upper poverty line, to identify the moderate poor, and the lower poverty line, to identify the extreme poor) are used to estimate Bangladesh’s poverty profile. Following standard practice, three measures are employed in the assessment of poverty: the headcount ratio, the poverty gap and poverty severity. The headcount ratio is the proportion of population living below the poverty line. The poverty gap measures the extent to which individuals fall below the poverty line as a proportion of the poverty line. Thus, the sum of the poverty gap gives the minimum cost of eliminating poverty, if transfers were perfectly targeted. Meanwhile, the squared poverty gap measures the severity of the poverty.

All three measures of poverty suggest impressive progress on poverty reduction in 2016 (Table 1). The poverty headcount fell from 31.5% in 2016 to 24.3% in 2016, implying an annual reduction rate of 1.2%. The poverty gap has also fallen, from 6.5% in 2010 to 5% in 2016, showing that the distance between average income/consumption among the poor and the poverty line reduced by 1.5 percentage points between the two survey points. Poverty severity, which is a weighted measure of the poverty gap, with weight being 2, also showed an improvement in 2016 from 2010. Progress has also been observed when using the lower poverty line to measure trends in extreme poverty.

The overall outcomes are encouraging in terms of the fight against poverty as well as attaining the target of zero extreme poverty by 2030. However, a deeper dissection of the data points to some concerns that require the attention of policy-makers and the adoption of appropriate strategies.

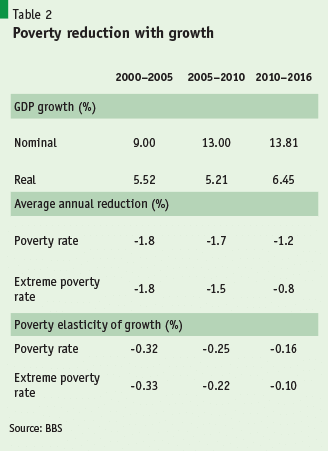

First, the rate of poverty reduction has been falling. Average annual reduction rates have been falling for moderate and extreme poverty. The reduction rate for moderate poverty, which was 1.8% in the 2000–2005 period, declined to 1.7% in the 2005–2010 period, and further to 1.2% in 2010–2016 – indicating a 0.6-percentage point reduction in the rate between 2000 and 2016 (Table 2).

The pace of reduction for extreme poverty has been even slower. This fell from 1.8% in 2000 to 0.8% in 2016, implying a 1-percentage point decline in the pace of poverty reduction between these two survey points.

However, this period (i.e. 2000–2016) experienced a rise in real gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 0.93 percentage points. The nominal GDP increase was 4.8 percentage points. Falling reduction rates in periods of rising GDP translate into falling poverty elasticity of growth. The poverty elasticity of growth for moderate poverty halved from 0.32% in 2000 to 0.16% in 2016. The drop is more pronounced for extreme poverty, which went down to 0.10% in 2016 from 0.33% in 2010. The fall in the rate as well as in elasticity is not surprising – and in fact is rather to be expected – as we are dealing with people who are either ultra-poor or incapable of integrating themselves into the current growth process.

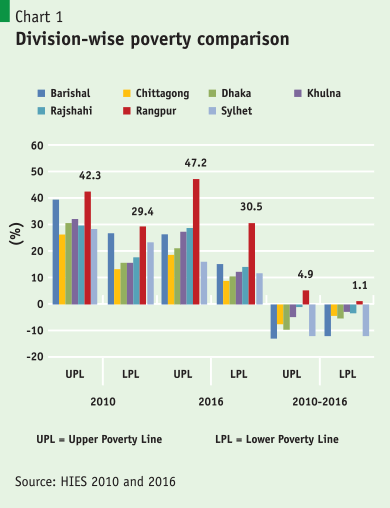

Second, what is happening to Rangpur? Poverty analysis by administrative divisions of Bangladesh reveals a surprising finding. Except for Rangpur division, poverty in all other divisions fell between 2010 and 2016 (Chart 1). Unlike all other divisions, Rangpur experienced a rise in poverty by almost 4 percentage points between 2016 and 2010. Kurigram and Dinajpur districts within Rangpur division reported exorbitant poverty rates of 71% and 64%, respectively – the same rates observed almost 40 years ago. At that time, considering Rangpur a poverty-stricken region, development partners, international and national non-governmental organisations and government put in place massive efforts to combat poverty. The outcomes seen tend to lead to the conclusion that these efforts were futile or not effective. Furthermore, they force us to conclude that poverty experts, policy-makers and development partners may have failed to identify the real reason for poverty in Rangpur.

Unlike all other divisions, Rangpur experienced a rise in poverty by almost 4 percentage points between 2016 and 2010. Kurigram and Dinajpur districts within Rangpur division reported exorbitant poverty rates of 71% and 64%, respectively – the same rates observed almost 40 years ago.

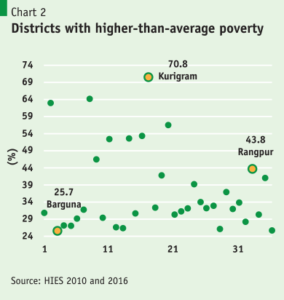

Third, poverty outcomes are uneven. More than half of the districts (i.e. 36) have higher moderate poverty rates than the national average rate of 24.3% (Chart 2). Another revelation is that almost 75% of these districts (i.e. 27) belong to the northern and southern parts of Bangladesh – the so-called lagging regions. Lack of district-level GDP data prevents us from arriving at a firm conclusion, but these outcomes tend to suggest that current growth is disproportionally benefiting relatively better-performing regions as opposed to the lagging regions.

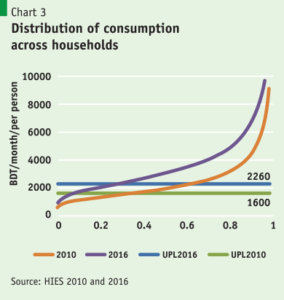

Fourth, rising inequality has dented the growth effect on poverty. Inequality has risen in Bangladesh (Chart 3). The cumulative consumption curves (CCCs) of 2016 and 2010 are shown here along with the upper poverty lines for 2016 (i.e. Tk 2,260 per person/month) and 2010 (i.e. Tk 1,600 per person/month). Given the rise in nominal income in 2016, the CCC of 2016 lies above the CCC of 2010 for all 10 income percentiles. However, the distance between the two CCCs widened for income percentiles 7–9, indicating worsening consumption between 2010 and 2016.

Contrasting cumulative consumption against the respective poverty lines clearly shows a headcount poverty rate of 31.5% in 2010 and one of 24.3% in 2016.

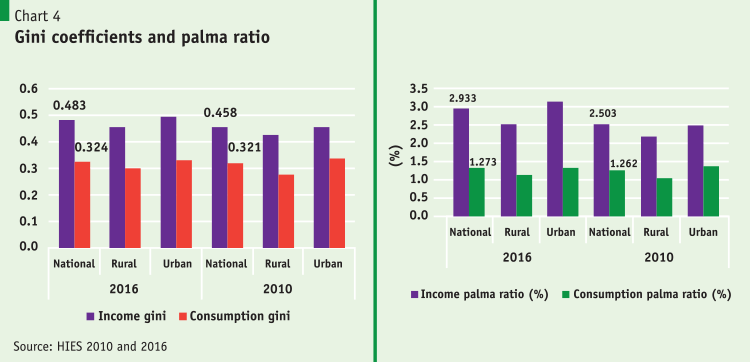

Two summary measures of inequality – the Gini coefficient and the Palma ratio, which is the ratio of the richest 10% of the population’s share of gross national income divided by the poorest 40%’s share –vindicate the above findings (Chart 4). Both the income and the consumption Gini worsened in 2016 compared with in 2010. The income Palma ratio for Bangladesh was 2.503% in 2010 and had increased to 2.933% by 2016.

Three observations can be drawn in conclusion. First, both the rates and the elasticity of poverty reduction are falling. Strategies based only on growth may not attain the desired reduction in poverty in future. Growth-based strategies must be supplemented by effective social security schemes with better targeting and enhanced transfer amounts.

Second, the story in Rangpur is a major concern. Bangladesh as a nation may have failed to identify the root cause of poverty in the division. An in-depth study should be conducted to enable a better understanding of the reasons behind this situation. This should help policy-makers design more effective poverty reduction strategies for Rangpur.

Finally, given that poverty rates in certain districts are much higher than the national average, government should establish a lagging region fund as prescribed in the 7th Five Year Plan. An adequately financed fund may go a long way towards increasing incomes and hence reducing poverty in lagging regions.