Jobless growth?

By

The job creation challenge

Job creation is one of the main concerns of politicians and policy-makers around the world. If anything, the concern is more pronounced in South Asia, where very large numbers of young people are reaching working age every year. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of South Asians aged 15 and above grew by 1.8 million per month, a trend that will moderate only gradually over time. Many of the entrants in this group are staying in school longer than their predecessors, and many may never seek a job. But still, many of them will, and it is not clear that South Asian economies offer enough good options for them.

Between 2005 and 2015, the number of South Asians aged 15 and above grew by 1.8 million per month, a trend that will moderate only gradually over time.

In Bangladesh, the debate about the job creation challenge is lively. Mohammad A. Razzaque and Nuzat Dristy convincingly make the case in the first article of the Policy Insight’s first edition, providing examples to show that ‘the challenge of job creation… is even more profound than it may seem at first sight.’ In a recent op-ed in the Daily Star, Selim Raihan analyses the anatomy of ‘jobless growth’ in Bangladesh and argues that, in addition to declining employment creation of growth, the quality of the new jobs created is a major concern.

In the latest edition of South Asia Economic Focus (the bi-annual World Bank macroeconomic update for South Asia), we contribute to the debate and analyse the relationship between growth and employment across South Asia. This article summarises our key findings; we encourage the reader interested in methodological issues to look at the full report.

Assessing what it would take to the keep the employment rate constant presents a useful benchmark. The employment rate is the share of the people aged 15 and above who work. Between now and 2025, the total population will increase in all South Asian countries, although it will do so at different paces. The increase is expected to range between 3% in Sri Lanka and 26% in Afghanistan. The growth of the working-age population will be faster, across all countries. The number of people aged 15 and above is expected to expand by between 8% and 41% by 2025, depending on the country.

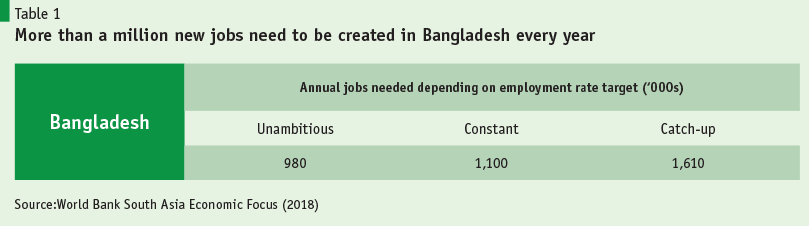

In Bangladesh, the working-age population is estimated to increase by 170,000 every month. In order to keep the current employment rate constant, 1.1 million additional jobs would be needed on average every year in Bangladesh from now until 2025.

A key question is whether rapid economic growth alone can generate the massive number of additional jobs needed. Concerns that the answer could be negative lie behind discussions on ‘jobless growth’. But, before reaching a conclusion, it is important to distinguish between short- and long-term effects of economic growth.

In the short term, growth can boost employment rates as greater labour demand pulls people out of unemployment and inactivity. Growth can also lead to better jobs, for example when farm employment is replaced by work in factories and offices. In the long term, on the other hand, growth could reduce employment rates. As countries become richer and living standards improve, families can afford to keep their children longer in school, the ill and the disabled can stay home and women may withdraw from the labour force. In assessing whether growth is jobless or not, it is therefore important to distinguish between these two effects.

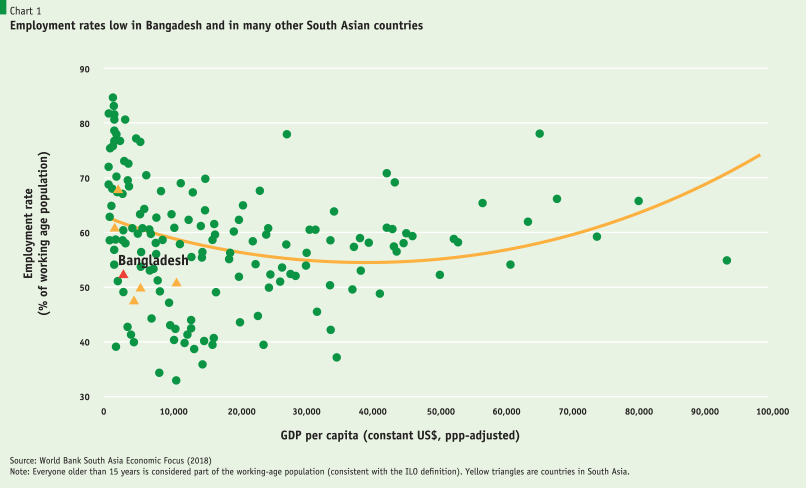

When comparing employment rates across countries with different levels of income per capita, a U-shaped curve emerges (see Chart 1). Many of the poorest countries in the world have very high employment rates. In these countries, people start working young and do not have the means to be unemployed or retired. Not only adult men but also women, the young and the elderly are part of the labour force. As countries become richer, school enrolment increases, old-age pension programmes are put in place and not every adult in a household needs to be at work. But this downward trend reverses at higher levels of income per capita. In richer countries, a growing number of youth reach tertiary education, and they are keen to work in the field of their study. Higher wages, safer transportation and workplaces and more easily available childcare also bring large numbers of women back into the labour force.

Low employment rates in Bangladesh are entirely the result of women working less than in other countries.

In Bangladesh, the employment rate is much below what is predicted, given income per capita and that the gap between the actual employment rate and the estimated U-shaped curve is 8.8 percentage points. Low employment rates in Bangladesh are entirely the result of women working less than in other countries. Employment rates among men are above the estimated U-shaped curve. But employment rates among women are consistently below, and the gap between the actual and predicted employment rate of women in Bangladesh is disturbing at 24.3 percentage points. A little over half of the women are predicted to be employed, but only a little more than a quarter actually find themselves employed.

So far, a foregone dividend

South Asia’s rapid demographic transition results in declining dependency ratios, offering an opportunity for faster economic growth. The dependency ratio compares the number of dependants, aged 0–14 and over the age of 64, to the working-age population, aged 15–64. In South Asia the dependency ratio decreased from 63% in 2005 to 55% in 2015, and it is expected to decrease further to 50% by 2025.

This change of the population’s age structure creates an opportunity for fast economic growth and rising living standards. Potentially, there could be more people earning an income for every child and elderly person needing support. Even if the productivity of those at work were to remain unchanged, income per capita would increase, because there would be more working people per capita. However, to reap the benefits of this ‘demographic dividend’, sufficient new jobs need to be created.

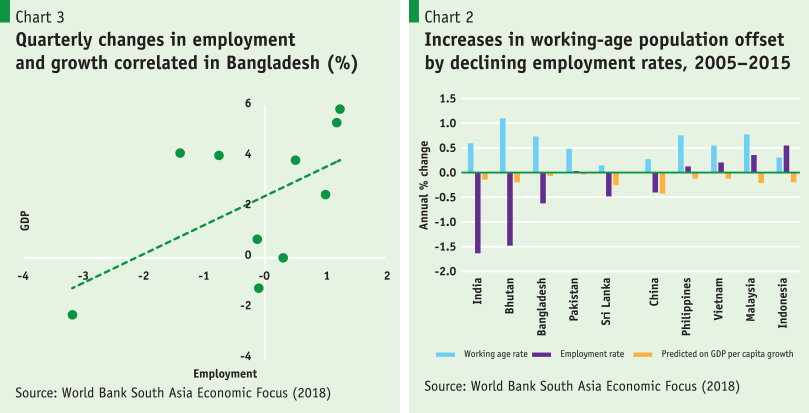

Not all countries have transformed their demographic transition into a demographic dividend to the same extent, however. The comparison between South Asia and East Asia is revealing in this respect (see Chart 2). In both cases, the U-shaped curve suggests employment rates were bound to decline with economic growth. But in East Asian countries employment rates declined less than the U-shaped curve would have implied, whereas in South Asian countries they declined more than could be anticipated.

Because of the decline in employment rates, the number of people at work in South Asia has not increased in line with the working-age population. For example, between 2005 and 2015, the share of the working-age group in the total population increased by around 0.5% in Bangladesh. But the employment rate decreased by on average more than 0.5% per year during that same period. Rapidly declining female employment rates in some South Asian countries are the main explanation for the difference with East Asia.

However, there is a silver lining in Bangladesh’s case. While male employment has declined by close to 1% per year, female employment has remained roughly constant. This establishes a sharp contrast between Bangladesh and other fast-growing South Asian economies. Understanding why Bangladesh has done better than its neighbours in this respect is important for research. The answer may well lie in the country’s success at developing labour-intensive manufacturing sectors that are intensive in their use of female labour, as is the case with the ready-made garment industry.

The employment response to economic growth

Estimating the short-term relationship between economic growth and employment rates has been the subject of a vast literature in advanced economies. There, the consensus is that rapid economic growth does indeed reduce unemployment rates in the short term, while slowdowns are associated with increases in unemployment. The literature is much scanter in developing countries, partly because of data limitations. Indeed, the unemployment rate is not very informative about the labour market situation in countries where few people can afford to remain idle.

An alternative, relative to the literature for advanced countries, is to study the relationship between economic growth and employment rates, rather than unemployment rates. But even then data gaps and inconsistencies muddle the analysis. Employment charts are seldom available with high frequency, and labour indicators differ in subtle but important ways across statistical instruments. Population censuses, economic censuses, household surveys and labour force surveys often define employment in different ways.

The implications of the gaps between definitions are amplified in economies where self-employment and casual work are the norm. A nine-to-five job, with a written contract and benefits attached to it, is easy to recognise. But relatively few jobs match this description in South Asia. In many cases, it is hence difficult to tell whether people are working, unemployed or out of the labour force, and the answers vary depending on the statistical instrument considered. The difficulty in measuring employment is exacerbated for women, as they tend to engage even more than men in activities falling in the grey area between work, unemployment and inactivity.

Comparing employment charts across sources without ‘standardising’ them first can be misleading. For example, in Bangladesh, the employment rate for 2016 is 53% according to the Labour Force Survey, but only 44% based on the Household Income and Expenditure Survey. Removing ‘extended work’ (e.g. fetching water, collection firewood, etc.) brings the two rates closer together. To address these concerns, in our report we extracted employment data from over 60 surveys from 2001 onwards in a fully transparent and replicable way.

Quarterly employment and gross domestic product (GDP) data are needed to rigorously assess the short-term response of employment to economic growth. In Bangladesh, annual employment data from the Labour Force Survey can be disaggregated by quarters based on the month of the survey. And annual GDP data can be interpolated with quarterly industrial production. Even though both resulting series are ‘noisy’, a positive correlation between them emerges (see Chart 3) – in other words, if growth accelerates so does employment generation.

More distant points in time need to be considered to assess how much employment is created overall per percentage point of growth. We follow a four-step procedure in this respect. First, employment rates are computed from every ‘standardised’ population census, household survey or labour force survey. Second, the estimated employment rates are applied to consistent demographic estimates of the working-age population. The advantage of using demographic series is that they are comparable over time. Estimates of the working-age population generated out of household surveys and labour force surveys show more erratic movements by comparison. Third, annual changes in employment are computed for all pairs of employment points available for each country. And fourth, all the annual changes in employment are divided by the annual percentage change in GDP over the corresponding period.

This four-step procedure is bound to lump together the short- and the long-term impacts of growth on employment. Given the many pairs of employment points, the procedure generates an array of estimates of the number of jobs created per percentage point of GDP growth, rather than a single number.

In Bangladesh, six of these estimates can be computed. They imply that 90,000 to 120,000 jobs have been created on average for each percentage point of GDP growth. But again, from a longer-term perspective, the focus should be on the more distant pair of employment points available for each country. By this metric, Bangladesh generates 110,000 jobs per percentage point of GDP growth.

Rapid growth alone is not enough

Having established that growth is not jobless, the question is how fast growth would need to be to address the job creation challenge. The answer depends on what the target for the employment rate is. One rather unambitious target would be to accept a gradual decline of the employment rate, as long as the decline is not faster than the U-shaped curve between employment rates and living standards would predict. In this case, the gap between the national employment rate and that of other countries at a similar level of development would remain constant. A slightly more ambitious target would be to keep the employment rate constant at its current level. And a truly ambitious target could be to catch up with the employment rate of other countries with similar income levels over a certain period – say, over 20 years.

These three targets for the employment rate – unambitious, status quo and catch-up – result in three different numbers of jobs ‘needed’ every year. Once a target employment rate is set, it can be multiplied by the forecast of the working-age population in the following year to obtain the target level of employment. The difference between that target level and the current employment level is the net job creation ‘needed’.

Setting the target for the employment rate is easy in the constant case, because it simply involves maintaining the current employment rate unchanged. Calculations are slightly more demanding in the unambitious and the catch-up cases, as it becomes necessary to use the estimated U-shaped curve described above. For the unambitious target, the target employment rate is allowed to decline according to the slope of the U-shaped curve; for the catch-up case, the target employment rate is set higher to fill some of the gap with other countries.

Proceeding this way, the net number of jobs to be created every year in the unambitious and the constant case in Bangladesh is not too far off the recent experience (see Table 1). But in the ambitious case the number is much higher than the region’s historic record.

Based on the estimated employment response to growth, very high but not totally unrealistic growth rates would allow for addressing the jobs challenge in the unambitious and constant scenarios. If the employment rate were allowed to decrease further, Bangladesh would need to grow by 9.3% per year. The growth rate needed to keep employment rates constant would be higher, at 10.3%. Again, this growth rate is high and above current performance, but could conceivably be attained if there was a concerted effort to boost economic performance.

However, growth alone will not be sufficient for employment rates to catch up with those of comparable countries. Even allowing for a 20-year transition period for the catch-up, the number of new jobs needed every year would be gigantic. Bangladesh would have to create over 1.6 million jobs every year. Assuming the same job creation per percentage point of growth as before, a growth rate of around 15% per year would be needed in Bangladesh. This growth rate is of course implausibly high, implying that rapid growth alone will not be enough. If Bangladesh is serious about increasing its employment rate, more jobs will need to be created for every percentage point of growth.

The nature of the jobs created is not fully encouraging

As economies develop, it is expected that individuals will move out of agriculture into more productive, non-agricultural employment. The transformation is notable in Bangladesh, where the agricultural employment rate decreased by 8 percentage points between 2005 and 2015 while manufacturing employment increased by 3 percentage points. From a sectoral point of view, it appears that structural transformation has been slower in the other South Asian countries, with the exception of Bhutan, where there was a clear shift in employment from agriculture to services.

If Bangladesh is serious about increasing its employment rate, more jobs will need to be created for every percentage point of growth.

Another important employment breakdown is by type of employment. Regular wage jobs are generally seen as better jobs, compared with farming, self-employment or casual work. But the news on this front is not particularly encouraging in South Asia. No doubt shares of casual work and unpaid employment declined across the board, but regular wage employment did not increase in a commensurate way. Again, Bangladesh does better than its regional peers in this respect. But still, the share of regular wage jobs in the working-age population increased by only 4.5 percentage points between 2005 and 2015.

If anything, recent developments in Bangladesh are worrying. In his op-ed, Selim Raihan shows that, despite strong output growth of 10.4%, manufacturing jobs declined by 0.8 million between 2013 and 2016/17. This is a disturbing annual average decline of 1.6%. What is worse, male manufacturing employment increased – so the decline is entirely the result of less female manufacturing. The number of women working in manufacturing in Bangladesh has declined by 0.9 million from 3.8 million to 2.9 million. This suggests that Bangladesh’s relative good performance during the past century has reversed most recently and many achievements may be at stake.

Based on the estimated employment response to growth, very high but not totally unrealistic growth rates would allow for addressing the jobs challenge in the unambitious and constant scenarios. If the employment rate were allowed to decrease further, Bangladesh would need to grow by 9.3% per year. The growth rate needed to keep employment rates constant would be higher, at 10.3%. Again, this growth rate is high and above current performance, but could conceivably be attained if there was a concerted effort to boost economic performance.

However, growth alone will not be sufficient for employment rates to catch up with those of comparable countries. Even allowing for a 20-year transition period for the catch-up, the number of new jobs needed every year would be gigantic. Bangladesh would have to create over 1.6 million jobs every year. Assuming the same job creation per percentage point of growth as before, a growth rate of around 15% per year would be needed in Bangladesh. This growth rate is of course implausibly high, implying that rapid growth alone will not be enough. If Bangladesh is serious about increasing its employment rate, more jobs will need to be created for every percentage point of growth.

The nature of the jobs created is not fully encouraging

As economies develop, it is expected that individuals will move out of agriculture into more productive, non-agricultural employment. The transformation is notable in Bangladesh, where the agricultural employment rate decreased by 8 percentage points between 2005 and 2015 while manufacturing employment increased by 3 percentage points. From a sectoral point of view, it appears that structural transformation has been slower in the other South Asian countries, with the exception of Bhutan, where there was a clear shift in employment from agriculture to services.

Another important employment breakdown is by type of employment. Regular wage jobs are generally seen as better jobs, compared with farming, self-employment or casual work. But the news on this front is not particularly encouraging in South Asia. No doubt shares of casual work and unpaid employment declined across the board, but regular wage employment did not increase in a commensurate way. Again, Bangladesh does better than its regional peers in this respect. But still, the share of regular wage jobs in the working-age population increased by only 4.5 percentage points between 2005 and 2015.

If anything, recent developments in Bangladesh are worrying. In his op-ed, Selim Raihan shows that, despite strong output growth of 10.4%, manufacturing jobs declined by 0.8 million between 2013 and 2016/17. This is a disturbing annual average decline of 1.6%. What is worse, male manufacturing employment increased – so the decline is entirely the result of less female manufacturing. The number of women working in manufacturing in Bangladesh has declined by 0.9 million from 3.8 million to 2.9 million. This suggests that Bangladesh’s relative good performance during the past century has reversed most recently and many achievements may be at stake.