Green RMG factories in Bangladesh

By

The ready-made garment (RMG) sector has become a key driver of the Bangladeshi economy: earning US$28.1 billion in 2016-17, employing around 4 million workers, and accounting for over 81% of the country’s total export earnings—essentially acting as the backbone of the economy. In order to stay ahead in a tremendously competitive market, the country’s garment industries are increasingly investing in avenues to boost their competitiveness and productivity. This has entailed taking giant leaps in investing in state-of-the-art factories that couple increased productivity and efficiency, with environmental sustainability and worker’s safety.

Bangladesh currently stands as the largest exporter of denim products to Europe – with more than a quarter of the market share (27%) , and the third largest exporter of denim products to the US (with 14% market share), trailing behind Mexico and China (as of March 2018). This comes on the back of recent estimates by McKinsey and Company, projecting the country’s RMG industry to grow to as much as $42 billion by 2020, while the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) set the bar even higher at a rather ambitious target of reaching $50 billion in exports by 2021. However, realistically, both of these projections are very unlikely to be achieved by the given time-frame.

Bangladesh currently stands as the largest exporter of denim products to Europe – with more than a quarter of the market share (27%) , and the third largest exporter of denim products to the US (with 14% market share), trailing behind Mexico and China (as of March 2018).

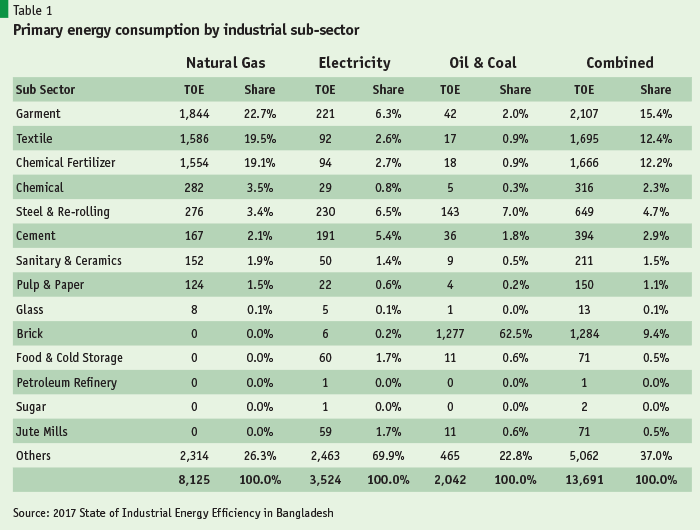

Nevertheless, the Bangladeshi textiles industry is acutely resource intensive, and requires extensive power, energy, and water resources to operate. For instance, the average factory in Bangladesh uses around 250 to 300 litres of water per kilogram of fabric produced—equivalent to the average daily water use for two people in Dhaka. This includes water used to weave, rinse and dye the cloth, as well as steam used in the printing and pressing process. In comparison, the global benchmark for fabric production is 100 litres of water per kilogram.

It is estimated that around 70% of the 1,700 WDF textile processing units which are responsible for considerable portion of the water demand and water pollution are located in the Greater Dhaka area. And the anticipated growth in this sector will only tighten the strain on not only the water supply (it is projected that to meet the anticipated growth, water demand could increase by 250% by 2030.), but also other resources such as power and gas—that already struggle to meet the existing demands of the industry.

Correspondingly, there is a need to ensure that the growth in the RMG sector does not come at the cost of environmental degradation and the misallocation of resources. Issues relating not just to water use, but other areas such as energy efficiency, recycling, waste water treatment, and green renewable technologies are all vital to the long-term success and sustainability of the Bangladeshi economy. As experience shows, investing in green technology can be good for business in terms of reducing costs and attracting more international customers. As such, an increasing number of manufacturers have been adopting results-based, return on investment (ROI) focus, helping them to identify and implement green projects that add value from an economic, environmental, and societal perspective.

Bangladesh leads the way

Bangladesh’s fast-growing RMG industry has been imperative in providing jobs and revenue for the country. Yet besides environmental concerns that naturally offshoot from a growing industry, it has also been plagued by a dismal worker safety record.

Why has this been such a prevalent issue? As producers will be quick to point out, in an increasingly competitive local and global market, consumers exert pressure on retailers to lower prices, which retailers in turn relay on to their supply chains. This often plays a key role as to why many factories resort to cutting corners, and have shown reluctance to invest in making improvements in past.

Nevertheless, having faced repeated calls to strengthen factory safety, security, and work-environment over the last few years, coupled with the growing awareness of industrial impact on the environment, Bangladesh currently leads the way in building structurally safe and environmentally friendly RMG factories, on a global level. At present, Bangladesh is home to some of the highest rated LEED certified green factories in the world.

The birth of the movement

Environmental concerns

Amidst the growing landscape of environmentally conscious consumers, it became apparent from a business point of view, that the convention of resource (and pollution) intensive business models, and negligence to safety issues could no longer be sustainable. And to maintain a competitive edge—and at the risk of losing business— many factories began turning-to and adopting green principles.

In 2013, IFC, in partnership with the NGO Solidaridad and the Dutch embassy launched the Bangladesh Water Partnership for Cleaner Textile (PaCT), which sought to provide a program through which buyers, factories, financial institutions, and the government could work together to reduce the environmental footprint of the textile and apparel industry. PaCT has partnered with 162 textile factories to date, in supporting them to implement sustainable, resource efficiency projects which have led to huge savings in resources and cumulative cost savings of around USD 10 million per year for the factories.

The investment entailed simple yet effective upgrades to equipment such as boilers, dyeing and rinsing machines, as well as simple fixes like insulating steam pipes and fixing leaks. Prior to the changes, the more efficient factories typically used around 120 to 170 liters of water to produce a kilogram of cloth. Following the changes, this had now dropped by almost 50%. These efficiencies also extend to the use of electricity and gas. And in the course of one year, the factories in the program together saved 1.2 million cubic meters of water, 16 million cubic meters of gas and 10 million kilowatt hours of electricity, while reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 32,000 tons.

Clearly in addition to the social, environmental, and marketing advantages of going green – vitally, it made financial sense, as well. This can be adequate incentive for any business to adopt green technologies and principles, and Bangladeshi factories have been no exception. Nevertheless, there has been an additional key dimension prompting the move towards greener, safer, and more sustainable factories in the country.

Nonetheless, as per PaCT reports, 29 out of 162 factories taking part in PaCT have reduced the use of resources— which is less than 20% of total participants— implying that 80% are either making slow progress or might have abandoned thhe idea altogether.

Safety concerns

The Rana Plaza disaster

RMG factories in Bangladesh have historically been plagued by a variety of issues, and dangerous working conditions, poor construction and a lack of oversight have long been concerns for Bangladesh’s garment industry. Yet, the pivotal moment came following the Rana Plaza disaster in April 2013, where more than a thousand people lost their lives; coming just months after the fatal fire at Tazreen Fashions in which more than a hundred lives were claimed. Dangerous working conditions, poor construction and a lack of oversight have long been concerns for Bangladesh’s garment industry, and following these disasters, it became explicit that fundamental changes relating to safety, inspection and compliance had to be made.

Bangladeshi factories subsequently faced much tougher scrutiny from international watchdogs such as ILO and the EC that pushed for more stringent labor rights and safety measures, amidst a growing shift in consumer awareness. To address these issues, in addition to improving measures to strengthen worker’s safety, ‘greening’ also acted as a key factor for the RMG sector to appease this mounting pressure and avoid losing market share in its most important destination – the EU and the US, that constituted around 64 and 18% of its export market in 2017, respectively.

In the wake of the tragedy, retailers formed two groups to address safety issues in Bangladesh. The first, Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, led by H&M and backed by Adidas, Benetton, Marks & Spencer, Tesco and others, and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety led by Walmart, whose members include Gap; Target; Hudson’s Bay Company, among others. Latest inspection reports from both organizations found less than 2% of factories in the country posing any safety risks. This is a commendable achievement given that the global safety risk rate stands at about 4%.

Granted that the Accord and Alliance monitored and inspected issues related worker and factory safety and not factory ‘greening’ per say, it nevertheless gave impetus to manufacturers to place greater emphasis on emphasizing on environmentally and structurally safe factories, while created pressure for the industry to improve rapidly. In this regard, it certainly led to a paradigm shift.

Coming to fruition

Bangladesh’s RMG sector – currently a $28 billion industry – leads the way in manufacturing, having established 67 Leadership in Energy and Environmental (LEED) certified green buildings in the country— the highest number in the world. Meanwhile, 222 additional factories have already been registered with the U.S Green Building Council (USGBC) for the LEED certification. Yet compared to the 4482 garment factories currently in operation in the country, as reported by BGMEA, these numbers remain meager.

Bangladesh’s RMG sector – currently a $28 billion industry – leads the way in manufacturing, having established 67 Leadership in Energy and Environmental (LEED) certified green buildings in the country— the highest number in the world.

Nevertheless, at present, Bangladesh is home not only to the highest number of green garment factories, but also boasts the highest number of top scoring green garment factories in operation in the world. Among the LEED certified RMG factories, 13 are rated platinum; the highest category according to LEED standards. Bangladesh runs ahead of Indonesia, that stands as the second largest with 40 green factories; followed by India with 30, and Sri Lanka with 10.

What is LEED and how does it work?

LEED is an internationally recognized green building certification system created in 1998 by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) that provides voluntary guidelines for the development of sustainable buildings around the world. It is a voluntary, points-based system where a rating level is achieved once a project meets all the prerequisites and a minimum number of points. Projects earn points based on specific criteria that they fulfill; the higher the number of points, the higher the level of certification granted (the minimum level is simply called “certification” and requires applicants to earn 26 of the 69 possible points. Projects that receive 33 points receive silver certification, those with 39 points earn gold, and those with more than 52 points earn platinum). Project managers have full discretion over which criteria they choose to meet in order to accumulate the necessary number of points.

Why is there a trend towards LEED certification?

A common starting point for most businesses in the current global climate is the desire to reduce their negative impact on society and the environment, while simultaneously growing sales. Finding ways to increase product efficiency understandably plays a vital role in this pursuit. In this regard, the intention of the LEED certification system is to standardize and certify commercial, institutional or high–rise residential buildings internationally. Currently, there are more than 91,700 LEED projects in 167 countries and territories across the globe.

Yet while there are critiques and concerns that LEED certification is more ‘ornamental’ than functional, it continues to be recognized as the industry standard for green buildings around the world. Showing the ability to adhere to LEED standards indicates practices of good compliance, as well as environmentally safe procedures – and importantly, this image can help companies attract and retain clients.

The advantages of LEED

Besides enhancing the company’s public image, LEED can lead to many tangible savings for a company. In 2011, an efficiency survey found that a LEED-certified Nike shoe factory in southern Vietnam used 18 percent less electricity and fuel and 53 percent less water compared with a typical factory. In another study, LEED-certified buildings have also been proven to use 25% less energy and a 19% reduction in aggregate operational costs in comparison to non-certified buildings. And factories in Bangladesh have reported using 40 percent less energy, 41 percent less water, and emitting 35 percent less carbon compared to a ‘regular’ RMG factory.

Building improvements have also been credited with enhancing working conditions and productivity for building occupants. However, these remain speculative and are yet to be empirically determined.

The disadvantages of LEED

Of course, participating in the LEED process adds time, effort, and costs to the design and specification phase of factories. According to BGMEA, a green factory requires 20-30% additional investment relative to non-green ones. Yet despite the high initial costs of construction, certification, consultation and implementation, LEED buildings typically have relatively short payback periods ranging from 3 to 5 years. Nonetheless, settings up green factories still remain far too expensive in Bangladesh owing to its heavy dependency on external sources for raw materials, as well as technical expertise. And given the magnitude of the added costs involved, factories adopting LEED certifications – let alone adopting green technologies – do not receive any premium from international buyers for their investments. For this reason, factories generally show reluctance to investing in, or adopting LEED certifications. Moreover, factory owners faced with higher investment costs need reassurance that their buyers will continue to place sufficient orders at feasible price levels. And in the absence of this, the initial investment required to implement green measures seem formidable.

LEED has undeniably galvanized the green building industry in a way that would have been unimaginable in Bangladesh even twenty years ago, and its popularity has no doubt encouraged criticism and competition as well. However, its widespread recognition has also made it a tool to garner free publicity and good will without ever having to prove that their structures are actually helping the environment.

A prevailing criticism of LEED pertains to the certification being pro forma, more about earning points than making concrete positive impact on the environment. This stems from the fact that LEED is indiscriminate in its weighting of credit points. For example, installing a bike rack outside a building receives the same number of points as redeveloping a brownfield site, even though bioremediation of brownfield is considerably more involved and expensive than installing a bike rack.

Crucially, LEED lacks post construction review of its projects. Its certifications are earned with the assumption that the building will perform exactly as designed, and LEED credits are awarded simply for reporting the lifecycle assessment of a design, and not what the final numbers might be. As a result, many projects end up performing much worse than expected, or even less efficiently than non-LEED buildings.

Where has the impetus towards LEED arisen from?

Pressure from buyers

Although Green Building or Green Industry is a relatively newer concept in Bangladesh, industrialists are increasingly moving towards exploring this sector to enhance their brand value and global image. LEED-certified buildings with lower operating costs and better indoor environmental quality are ostensibly more attractive to a growing group of corporate, public and individual buyers. Although buyers do not offer higher prices for apparel produced in green factories, nonetheless they do prefer placing orders with factories that are fully compliant and certified by globally recognized agencies, such as the likes of LEED. As alluded-to, foreign buyers are increasingly concerned not only concerned about the product quality, but also about the social, ethical and environmental standards that factories adhere to – as a response to the growing awareness among consumers globally.

LEED-certified buildings with lower operating costs and better indoor environmental quality are ostensibly more attractive to a growing group of corporate, public and individual buyers.

Global brands such as H&M, for instance, have launched their strategy for 100% circularity, which includes favoring factories investing in energy efficiency, reduction and recycling of water, renewable energy, and other green technologies over ones that do not. Moreover, more than 200 of the world’s biggest clothing brands and retailers, that include Walmart, Target, Zara, Marks and Spencer, Adidas, L.L. Bean, and Benetton, have pledged to do business only with factories that comply to specific economic, human resources, and ethical conduct.

In a Nielsen global survey on corporate social responsibility, more than half (55%) said they were willing to pay extra for products and services produced or offered from companies that were committed to positive social and environmental impact—a jump from 50 percent in 2012, and 45 percent in 2011.

Additionally, a report by Dodge Data & Analytics showed that while client demand had consistently been an important trigger in the studies conducted in 2008 and 2012, it took a significant leap in 2015 as one of the top triggers driving future green activity, shooting from 35% in 2012 to 40% in 2015.

Potential savings

In 2015, the Danish Embassy took initiative to conduct 4 energy audits at 4 different RMG factories in Bangladesh. As part of the audit, 49 different measures were identified within the areas of utility, production, environment, savings, technology and energy source, etc. And one of the primary findings from the report was that the biggest potential for savings lay within the utility area of the factories.

For Plummy Fashions, the highest LEED rated knit factory in the world, the savings on electricity has been substantial. Consumption of electricity prior to adopting green technology averaged to 350 kilowatt per hour for the 56,000-square-foot, two-floored factory. Plummy Fashions shaved this off to 200kw by adopting green technology. A typical factory of comparable size and capacity requires on average 550-kilowatt electricity to operate. Plummy saves up to 39.1 percent electricity by using natural light, while emitting 38 percent less carbon emission.

What the government is doing about it

BGMEA, the apex trade of garment manufacturers in Bangladesh, has been making efforts to promote environment friendly green concepts among entrepreneurs and motivate its members to adopt energy-efficient technologies and resource-efficient production machinery. The BGMEA continues to cooperate with IFC in implementing the PaCT project, and has recently signed an agreement to execute the second phase of project.

Meanwhile, according to Bangladesh Bank, in the 2015-16 fiscal year, banks and other financial institutions disbursed Tk46,590 crore in loans. Of that amount, Tk39,695 crore went to green factories, most of which are in the RMG sector. Additionally, to encourage all industries to establish eco-friendly factories, Green RMG factory owners are to enjoy 1% cut in corporate tax from the fiscal year 2017-18, as well as benefit from a reduced corporate tax to for the apparel sector: down to 15% from 20%. The government also proposed a 14% corporate tax for green RMG factories.

Conclusion

Against all odds, Bangladesh has managed to achieve remarkable developmental milestones, in recent years. The country has managed to make thousands of export garment factories safe, improved workers’ rights, and managed to achieve significant gains in safe environmental practices. Yet while some factories have managed to afford multimillion-dollar effluent treatment plants, a majority of others have not, given the level of costs involved.

Conventional wisdom has historically presented a dichotomy: help the environment and hurt your business, or harm your business while protecting the earth. In recent times, however, a new wisdom has emerged that promises the ultimate reconciliation of environmental and economic concerns. In this new world, both business and the environment can win. Being green is no longer a cost of doing business; it is a catalyst for innovation, new market opportunity, and wealth creation.