Priorities for the new government: securing the targets for vision 2041

By

Political economy context

Following the National Elections on December 30, 2018, a new National Government is in place. An immediate challenge for the new government is to firmly address the macroeconomic stability concerns linked to the banking sector, fiscal policy and balance of payments challenges, while addressing the long-term development goals defined under Vision 2041. Although there is no inconsistency between the two objectives, addressing the immediate stability concerns is a pre-requisite for travelling the development path entailed under Vision 2041.

Setting priorities

The task of setting development priorities is essentially a matter of political economy. A complex and large economy like Bangladesh faces many challenges, some of which are of immediate concern and some are longer-term in nature. Bangladesh also faces several constraints relating to institutions, financing, governance and administrative capacities. These constraints are long-term in nature and will require concerted long-term efforts to overcome them. Yet, development must proceed and policies must be identified and implemented. The art of priority setting involves identifying those high-priority policies that can be implemented within the existing constraints with strong political leadership. Their implementation will ease the constraints in some fashion in the future, while leading to the path of the long-term development goals. Given the financing and administrative constraints, the high-priority list will be limited to a few that will likely yield the maximum benefit in terms of the long-term development goals.

A complex and large economy like Bangladesh faces many challenges, some of which are of immediate concern and some are longer-term in nature.

In this article, I suggest 5 top-priority reforms that I believe are of most relevance to the Bangladesh economy right now and that have a major link to the long-term development goals. Listing the 5 noted in this article does not by any means reduce the importance of other issues not listed. The choice is a political economy challenge and policy makers will have to use their judgement based on cabinet review and approval.

Top 5 reform priorities

Vision 2041 seeks to achieve a two-step time bound goal: secure upper middle- income status and eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031; and achieve high-income status and nearly eliminate absolute poverty by FY2041. The development gaps between the situation today in FY2019 and the targets set for FY2031 and FY2041 are huge. Sceptics might even question the feasibility of these targets. In my view the debate about the realism of these long-term goals is less fruitful then asking the question what will it take for Bangladesh to secure these targets or at least approach them with determination.

Against the backdrop of these long-term development goals and the current macroeconomic environment of Bangladesh, the top five reform priorities in my view are:

- Reforming the banking sector.

- Reforming fiscal policy.

- Reforming the infrastructure policies.

- Reforming the urban sector.

- Reforming human development and social protection.

Reforming the banking sector

Reforms over the past two decades or so have greatly improved the quantity and quality of banking services in Bangladesh. The urban areas are well served by a competitive banking sector with convenient access and a range of banking products, including electronic banking. The rural areas are increasingly coming under the spread of commercial banking, supplemented by the large growth of microfinance institutions. A growing number of unbanked rural populations are being serviced through mobile financial services. Interest rates are falling and many borrowers with good track record are getting loans at single digit interest rate.

Nevertheless, there is still a large unbanked population and there are many micro and small enterprises that do not have access to banking sector credit. Policy effort should therefore seek to consolidate the gains and focus the banking sector agenda to achieve the country’s dream to secure the Vision 2041 targets. Unfortunately, there are signs that some deep fault lines are emerging. These fault lines can broadly be grouped under two headings: the growing incidence of non-performing loans; and the growing asset concentration among single borrowers. Closely related is a third fault line in terms of the lack of autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank (BB). These fault lines require to be addressed swiftly to prevent the risk of a banking crisis.

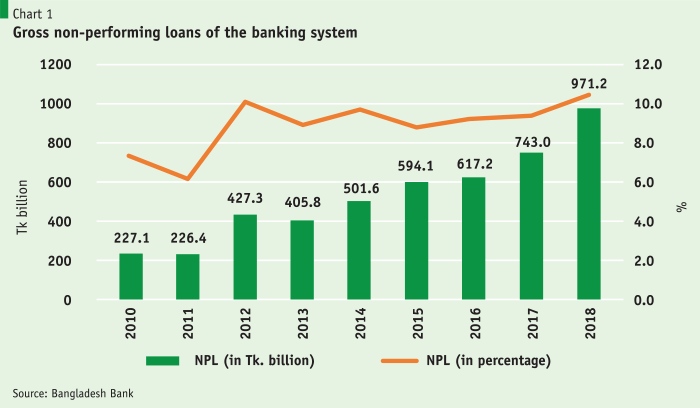

Growing incidence of non-performing loans (NPL): Chart 1 shows the recent trend of NPLs for the banking sector. The amount of NPL climbed to an astounding Taka 743 billion (US$8.8 billion) in 2017, which is 90% of Bangladesh’s actual annual development plan (ADP) spending for FY2017. NPL is projected to have grown further to Tk 971 billion ($11.8 billion) in 2018. While traditionally the NPL phenomenon is large in public banks for well-known governance problems, the evidence of rising NPLs in private banks owing to political interventions is a huge problem that could destabilise the banking sector.

One of the prudential instruments for portfolio management is the selection of bank board members based on the “fit and proper” test. There is a widely shared concern in the banking professional community that the quality of the boards in many private banks is weakening. There is a growing dominance of non-professional private bank boards, often based on family connections, and the BB has very little authority in practice to correct that. As a result, lending decisions are not always made on solid business evidence but done based on connections. In this case, the risk of NPLs will obviously increase.

Growing asset concentration: Prudential norms usually limit the banking sector’s exposure to an individual and or family to a small number (usually to 10%) with a view to protecting the domino effect of the collapse of a business on the banking sector. A large Bangladeshi business dealing with speculative commodity trading, stock market shares, or real estate transactions can easily go under that could lead to its inability to service its bank loans. The larger the exposure of this firm, the larger the risk to the banking sector. The health of the banking sector needs protection against this risk by setting banking sector-wide exposure limits and close monitoring.

Bangladesh Bank autonomy: In advanced economies the independence of the Central Bank is an important indicator of good governance. As Bangladesh aspires to attain upper middle-income and high-income status, it must also reform its institutions including the establishment of a professional and autonomous central bank.

The way forward: A combination of growing NPLs and asset concentration, if unchecked, can jeopardise the stability of the banking sector. Swift actions are needed to address these concerns. The most immediate step would be to increase the authority and autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank to strengthen supervision of all banks (public and private) and apply the full prudential norms including fit and proper test for all bank boards (public and private), limiting family representation in these boards to a safe level, establishing safe limits on single borrower exposure based on total bank assets, and applying prudential norms to the number of bank licenses and individual bank ownership. Along with this, the public banks must be reformed in two steps. In step one, public bank management must be depoliticised and turned into autonomous corporations with professional management and required to earn a profit. All political interventions in board and staff appointments and loan approval and recovery decisions must be stopped. A hard budget constraint on public banks must be imposed with zero transfers from the state budget for recapitalistion. In the second step, all except one bank should be privatised. The one remaining bank should be converted into a narrow bank that does only Treasury functions. Finally, the culture of loan default must be stopped with full loan recovery effort as provided under the law and supported by fast-track loan recovery courts.

Fiscal policy reforms

Achieving the income growth and poverty reduction goals of Vision 2041 will require major improvements in policies, institutions and resources. The resource mobilisation challenge for the public sector is in particular daunting. Total public expenditure as a percentage of GDP is around 16%, which is low for a country with 170 million people. While the efficiency of public spending is also low, and the government should improve this, total public spending must increase to help finance long-term development.

One positive aspect of the fiscal management is the maintenance of a prudent cap on budget deficit to around 5% of GDP. This has been helpful in reducing inflationary pressure, avoiding a crowding-out feature for private sector credit, and keeping the debt to GDP ratio to a sustainable level. As against these positive aspects, tight fiscal space is a major development constraint. The tax to GDP ratio in Bangladesh is very low. It was 7.9% in FY2009 and increased modestly to 9.3% in FY2018. The non-tax revenue to GDP ratio is not only low, it has fallen as a percentage of GDP from 1.9% in FY2009 to 1.2% in FY2018. So, total revenues have grown from 9.8% of GDP in FY2009 to 10.5% over the past 9 years, which suggests an average increase of less than 0.1% of GDP per year. This lacklustre revenue performance is explained by the absence of any major fiscal reform in this period. Low revenues in the face of fiscal prudence have limited spending at 16% of GDP in FY2018, leaving very little fiscal space to do anything meaningful to meet the spending gaps in infrastructure, health and education, and social protection.

…total revenues have grown from 9.8% of GDP in FY2009 to 10.5% over the past 9 years, which suggests an average increase of less than 0.1% of GDP per year.

The way forward: The fiscal strategy proposed in the 7FYP is sound and remains valid. The challenge is that it needs to be implemented. Actions will be needed on both the tax and non-tax front. The strategy to increase taxes by 4.8% of GDP over a 5-year period as envisaged under the 7FYP is ambitious but necessary and doable. Political will is necessary. The main elements of the tax strategy are as follows.

- Implement the VAT 2012 Law

- Overhaul the corporate tax regime by lowering corporate rates to a maximum of 25% over a three-year period with few exceptions. Eliminate most tax exemptions. Bring all sectors to the same corporate taxation regime including the readymade garments (RMG) sector.

- Vastly simplify the personal income tax regime by eliminating wealth and income-expenditure statements, which is an important source of corruption; ensure electronic filing and payments; remove all direct interface between taxpayer and tax collector. This will improve voluntary compliance and expand the tax base even to the rural areas where digital technology is making progress.

- Overhaul the audit system. This should be very selective and productive in terms of revenue yield. This should be a computer-based system that identifies audit candidates using a scoring method based on pre-determined red flags. Generally, these red flags should be designed to be revenue productive and target genuine tax evaders. Audits should not be targeted to harass political opponents or for corrupt practices.

- Eliminate the wealth tax and introduce a proper property tax system based on a realistic valuation of personal and commercial properties and a meaningful tax rate.

- Sharply reduce the incidence of trade taxation by overhauling the supplementary duty and regulatory duty system. The negative revenue impact can be neutralised through streamlining the highly differential rates of import duties and through the VAT system that will apply to both imports and domestic goods.

- Introduce a carbon tax on fossil fuel use. The revenue impact can be substantial while reducing carbon emission and promoting the use of clean energy. To minimise the adverse effects on cost, it can be done in steps starting first with petrol and diesel and then moving to other fuels. China and India have introduced a carbon tax in recent years with considerable success.

- Improve tobacco taxation by increasing the tax rates on low-end cigarettes and biris and by bringing all biri production in the tax net.

- Strengthen the research and administrative capacities of NBR through international technical assistance and partnership with local research institutions. To facilitate research and planning, all tax data should be computerised. Online filing will facilitate this.

While the bulk of the new fiscal space will come from taxation, some important contribution can be secured from non-tax sources as envisaged in the 7FYP. If well implemented, total non-tax revenues can rise to 2% of GDP in the next five years.

The largest gain can be made through better use of assets invested by the government in state-owned commercial banks (SCBs) and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Presently both are on average running losses and depend on budget transfers for survival. Additionally, the stock of outstanding NPLs of SCBs (estimated at $5 billion in FY2017) and outstanding debt of SOEs (including utilities and authorities) (estimated at $24.5 billion in FY2017) present a huge contingent liability for the government that must be systematically addressed.

A reform of SCBs and SOEs are of the highest priority to ensure sound budget management over the medium term. The government must adopt a policy whereby the SCBs and SOEs are both required to earn a profit based on a reasonable rate of return on invested assets.

This should be most easy for SCBs, because banking inherently is a profitable business where bank loans enjoy an average spread of 4.5% over cost of deposits. Efficient banks should typically limit their administrative cost to about 1.5-2.0% of the spread, leaving the rest for profit. A loss happens only when bad loans are made and when collection of interest and principal repayments are not enforced. Both these bad choices are mostly politically motivated and can be corrected if there is a political will.

The SOEs present a more complex challenge and may require some technical restructuring and better pricing policies. But these can be addressed over the medium term.

Most importantly, both SCBs and SOEs must be delinked from the national budget through a hard budget constraint. In the face of severe fiscal constraint amidst the need to finance essential development spending, continued injection of budget resources to salvage inherently profitable public assets that are being damaged by bad management and political interventions is a poor and unsustainable fiscal strategy and must be stopped and reversed quickly.

Reforming the infrastructure policies

In the globalised environment of trade and investments it is most important for countries to be competitive and the quality of infrastructure is a key input for it. Energy and transport are essential elements of the modern production and distribution processes and the efficiency and relative cost of these inputs are often a key determinant of competitiveness in the global economy. Bangladesh has understood the importance of infrastructure and over the past 10 years has put top priority in public development spending for developing power and transport infrastructure. This investment has paid off with most progress in the generation of electricity with an unprecedented growth in power generation (13.4% per year between 2008 and 2018). Access to electricity has improved, power outages have been curtailed and transmission and distribution losses have been reduced. The transport network has also expanded in highways, bridges, roads and ports that have supported the growth of trade and commerce.

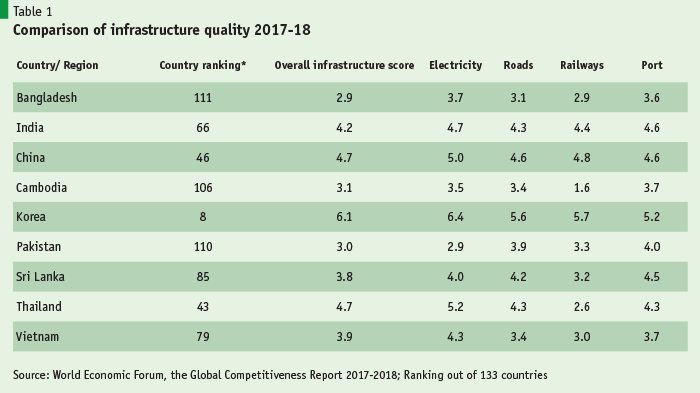

Despite this progress, the quality of infrastructure services lags behind major competitors (Table 1) The gap is particularly large when compared with upper middle-income countries (China, Thailand) and even larger when compared with high-income countries (South Korea), thereby illustrating the magnitude of the infrastructure gap and the challenges ahead.

A review of past performance shows several policy challenges that have to be addressed. First, despite high priority, total annual public spending on infrastructure (4% of GDP) is far lower than what is needed to tackle the infrastructure deficit (7% of GDP). Second, there is a major problem with the development of primary energy resources. Gas reserves are fast dwindling and no alternative domestic energy sources have been developed so far. Domestic coal development has not happened and renewable energy efforts are yet to take off. The focus on imported coal and LNG is facing financing and infrastructure constraints. Third, in the transport sector, there are severe implementation capacity constraints that have considerably slowed project completion. The transport sector strategy also suffers from inadequate attention to the development of a balanced inter-modal transport network. The emphasis on the development of low-cost inland water transport is lacking, while railway sector suffers from serious management constraints. Fourth, the urban traffic congestion, especially in Dhaka, has reached nightmare proportions that has sharply reduced productivity and threatens to choke off the growth momentum.

The way forward: The infrastructure challenge is daunting but can be addressed with determined efforts. The progress achieved in the power sector sets a good example of how to move forward. Specific policies moving forward include:

- Adopt a comprehensive infrastructure financing strategy: It is obvious that the amount of funding necessary to meet the infrastructure quality gap much exceeds the capacity of the national budget even with an aggressive resource mobilisation strategy as identified above. A comprehensive and sustainable infrastructure financing strategy requires a combination of tax funding, public-private partnership (PPP) and cost recovery policies based on beneficiary-pays-principle (BPP). The power sector financing has already shown the way on PPP financing for power generation. Future effort should focus on applying the same policy for power distribution and primary energy resource development, especially renewable energy. In transport, the scope for PPP investment is large. This requires converting the present PPP nodal agency into an internationally-competent professional body managed by experts who have experience in mobilising international financing for PPP infrastructure projects rather than as a government bureaucracy. Perhaps the biggest challenge is to institute proper pricing policies for power, energy and transport services. Most of the services, especially power and primary energy, are commercial services and should be fully financed through cost recovery as in most middle and high-income economies. Bangladesh now needs to change its mindset from subsidies to profitability for all publicly provided commercial goods and services so that expansion programs are largely self-financing.

- Develop a long-term primary energy supply policy: This involves a mix of several policies. First, a comprehensive domestic coal policy must be developed that meets international standards on environment, resettlement and safety and implemented in partnership with NGOs and the affected population. Second, the infrastructure required for use of imported coal and LNG must be fast-tracked with PPP financing. Third, utmost attention should be given to the development of all forms of renewable energy including from wind and solar sources. Incentive policies must be improved in favour of these sources through a combination of eliminating fossil fuel subsidy, imposing a carbon tax, and providing subsidies for development and adoption of renewable energy as necessary. Finally, the use of energy trade needs rapid expansion through stronger partnership with India and new partnerships with Nepal and Bhutan.

- Developing inter-modal transport network for efficient transport flows: The bulk of the passenger and cargo traffic presently depends upon high-cost road transport network. The current transport strategy continues to put emphasis on road transport that is high cost in both financial terms and in terms of environmental degradation. This approach is already reaching its natural limits as land scarcity increases. Future transport development strategy must improve the inter-modal balance with high priority assigned to inland water transport (IWT) and railways. This improved balance will reduce cost and improve efficiency. Development of IWT will also promote regional trade and create jobs for the rural areas. Development of IWT and railways will require a combination of higher investment, improved regulations for safety and governance improvements. The agenda is well- known to the government but requires concerted implementation efforts.

- Strengthening implementation capacity for road transport projects: A number of actions can be taken to strengthen project implementation capacity including: closely monitoring completion of all large transport projects, ensuring timely release of funds, linking new investment approvals to the record of project implementation, improving procurement policies, paying greater attention to project design before project approval, ensuring project implementation readiness as an important criteria for project approval, and strengthening capacities of line ministries and public agencies through recruitment of special skills from private sector on a contractual basis. For large and complex projects, international competitive bidding process should be followed with emphasis given to turn-key project contracts with strict monitoring and penalty clauses for timely delivery of projects in agreed quality and price.

- Implementing a well-managed urban transport strategy: The strategy for urban transport should aim at improving transport and traffic infrastructure so as to meet existing and potential demands, and developing an integrated and balanced system in which all modes (motorised and non-motorised) can perform efficiently and each mode can fulfil its appropriate role in the system. The main elements of an urban transport strategy are: provision of rail-based mass rapid transit initially in Dhaka and eventually extended to all divisional cities; provision of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) that is characterised by dedicated lanes for rapid movement of buses for all divisional cities; creating special lanes for pedestrians and cyclists; eliminate all fossil fuel subsidies including for CNG, while focusing subsidies on mass transit options; promote high efficiency and alternative fuel vehicles; introduce Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) initially in Dhaka and then extend to other divisional cities; strengthen linkages with cities and towns around Metropolitan Areas through bus and rail-based commuter services; emphasise coordinated development of land use and transportation planning in order to facilitate access to such basic necessities as workplaces and socio-economic facilities; encourage commercial parking facilities through private investment; enforce parking regulations for all with penalties for non-compliance; introduce time of day use restrictions in heavily congested roads; and introduce entry fee during peak hours for heavily travelled roads.

…the use of energy trade needs rapid expansion through stronger partnership with India and new partnerships with Nepal and Bhutan.

Reforming the urban sector

Over the 50 years during 1961-2011, the Bangladeshi population nearly tripled in size, growing from 51 million to 150 million. The urban population increased nearly twenty-fold, galloping from less than 3 million in 1961 to 42 million in 2011. Owing to these population dynamics, the share of urban population grew from around 5% in 1961 to 28% in 2011. It was projected to have reached 31% in 2017. The urbanisation trend started early from the 1960s and gathered momentum in the 1970s after independence. The growth of urbanisation was particularly rapid between 1974-1981. Since 2001 the pace has stabilised at around 3%, but still 2.5 times faster than the national population growth.

A major characteristic of the ongoing urbanisation experience in Bangladesh is the heavy concentration of urban population in the capital city of Dhaka. Along with population there is also a heavy concentration of economic activities in Dhaka. The next largest city is Chittagong, which is about a third the size of Dhaka. It is a port city and has also attracted considerable private sector interest. Dhaka and Chittagong together have served as the primary growth centres for Bangladesh over the past two decades. The other six divisional city centres, Rajshahi, Khulna, Sylhet, Barisal Rangpur and Mymensingh have failed to take-off as growth centres.

The pattern of urbanisation by and large has been haphazard. Some of the characteristics of this disorganised and unplanned urbanisation have been particularly worrisome, especially regarding urban transport, housing, basic urban services (water supply, sanitation, drainage and solid waste management) and the urban natural environment (air and water pollution), although progress with urban poverty reduction has been solid.

The PP2021 recognised the gravity of the urbanisation challenge and its long-term nature. The strategy called for a major overhaul in the approach to urbanisation. It emphasised balanced development of many urban centers instead of Dhaka-centric urbanisation. It suggested a major change in the urban governance by emphasising political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation and participatory development.

Notwithstanding this visionary approach to urbanisation, the PP2021 urban strategy has not been implemented. Substantial investments in urban infrastructure and services have been made but the large backlog of unmet demand and the continued rapid growth of urbanisation have outstripped those investments. At the institutional level, while progress has been made in implementing political decentralisation on the basis of elected management of City Corporations and Municipalities (Paurashavas), nothing else has moved. The urban bodies have very little mandated responsibilities with considerable overlap with other government entities. Fiscal decentralisation is yet to happen. Consequently, the urban bodies remain heavily dependent on national government funding. Own resource mobilisation is very low (collectively about 0.16% of GDP), which does not even meet their current expenses. Unbalanced urbanisation has further accelerated as Dhaka’s primacy increased further between FY2010 and F2018. Urban traffic congestion has further intensified. The urban slum population has grown. Importantly, the urban natural environment continues to deteriorate owing to difficulties in managing urban sanitation and solid waste. Drainage problems have multiplied, as a few hours of heavy rain create massive traffic jam in Dhaka city due to road-level water logging.

The way forward: The urban agenda has clearly assumed added urgency. Good practice international experience suggests that there are two big picture agenda that will have to be addressed. First is the need to address the urban finances issue. And second is the need to tackle the urban governance challenge. The two are inter-related and will have to go together. The basic challenge is to establish a system of accountable city government that is publicly elected, enjoys considerable political and administrative autonomy, is responsive to the needs of the residents and not to the national government, and has considerable financial autonomy.

The implementation of these reforms requires proper changes in the legal framework that clearly defines the roles and responsibilities of the urban LGIs in a manner that avoids duplication, especially from competing bodies of the national government. The Government should establish a National Task Force of urban experts to review relevant international experiences and give a recommendation to the Cabinet for review and approval. Once done, this should be become legally binding through an Act of the parliament. The Act should also clarify the degree of political and administrative autonomy granted to urban LGIs and the financing options.

The financing options will be some combination of assigned taxes (which is usually the property tax), user charges, block grants from the national government and limited scale borrowing for high-priority, high return urban infrastructure based on municipal bonds. The level of fiscal decentralisation granted to the urban LGIs would be a part of the Act and will define the basis for national budget transfers to urban LGIs, taxes assigned to them and authority for public borrowing. Government transfers would be reformed to provide greater transparency and predictability of the transfers. The transfers will need to be matched to assigned responsibilities. In designing the transfer system, the basic principles would include factors relating to population, poverty, endowment and performance. Cities that have a larger share of the population, higher poverty and weaker options for local tax mobilisation will receive larger grants. This equity principle would facilitate the growth of lagging cities like Khulna, Barisal, Rangpur, Rajshahi and Mymensingh. A two-tier transfer system combining equity and incentives (performance) could be used to promote competition among cities. Thus, cities that are innovative and make special effort to improve its efficiency of service delivery would have opportunities to tap special incentive funds from the national government. The national budget could also earmark special-purpose funds to promote national development goals related to health, education, environment, social protection and poverty reduction.

Reforming human development and social protection

A fundamental theme of Vision 2021 and the associated PP2021 is the achievement of a development outcome where citizens will have a higher standard of living, will be better educated, will face better social justice, and will have a more equitable socio-economic environment. This emphasis on equity and social justice is a hallmark of PP2021 and remains embedded in Vision 2041.

Human Development: A review of progress shows considerable momentum was gained. All human development indicators continued to improve under the PP2021 including life expectancy, infant and maternal mortality, total fertility rate, population growth rate, child nutrition, adult literacy and education enrolment and completion rates at all levels. Life expectancy surged to an amazing 71.6 years in 2015, which is higher than many countries with higher per capita income.

Despite this progress, there are two major gaps. First concerns the quality of education and the second concerns labour skills. The education quality gaps are severe at all stages of the education cycle. There is considerable wastage reflected in school dropouts. In the area of skills, there is huge quality challenge reflected in considerable mismatch between demand and supply. Some 23% of the work force have zero education; 31% have only primary education; and only 6% have tertiary education. This education profile of the work force is inconsistent with the skills needs of an upper middle income and a high-income country. This also severely constraints the ability to convert the demographic profile of a growing work-force age population into a true demographic dividend.

A major constraint is the continued low level of spending on education and training. At 1.8% of GDP, Bangladesh spends much less on education and training from the budget than in upper middle-income countries. Heavily centralised management of schooling from the capital city of Dhaka is another constraint. In training, stronger partnership with the business sector is needed to make training demand-driven.

Social protection: International evidence shows that a comprehensive and well-funded social protection system is the most effective way of reducing income inequality and protecting the poor and vulnerable population from external shocks and other uncertainties. Bangladesh has generally taken a positive approach to social protection by giving it priority in budget allocation. The coverage of social protection benefits has increased over the years and evidence from HIES 2010 shows that social protection programs have helped lower poverty.

Government spending on social protection excluding civil service pensions peaked at 1.9% of GDP in FY2011 but since then it has been on a declining trend owing to budgetary constraints. It fell to 1.2% of GDP in FY2017. In addition to a financing constraint, several efficiency and governance issues emerged with the administration of the existing social protection system. Problems include: a proliferation of programmes (95 in FY2013); too many small programmes with low average benefits; programmes not strategically selected to fit all aspects of the Life Cycle support needs with large gaps for many vulnerable population; programme benefits not well distributed to the poor and vulnerable; evidence of waste and leakages; expensive and inefficient programme administration spread over too many ministries (30 agencies); no coverage of modern employment benefits such as unemployment insurance; and no system of Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E).

In view of these concerns the government in 2015 adopted a major new social protection strategy known as the National Social Security Strategy (NSSS). This was a comprehensive new strategy that combined the best features of a modern social protection system including social insurance with the realities of Bangladesh. The multitude of programmes was consolidated into a few along the Life Cycle Framework to encompass all age-groups of the vulnerable population starting from maternity to old age. Benefits were consolidated into meaningful cash-based transfer programmes to be administered mostly electronically. A substantial administrative reform was suggested to improve efficiency, improve targeting, strengthen oversight and avoid leakages. A strong MIS with emphasis on beneficiary database and M&E systems were incorporated in the strategy. A system of social insurance linked to employment was also incorporated. Nevertheless, the implementation of the new NSSS has lagged behind with only a limited number of programmes administered by the Ministry of Finance being done on a pilot basis.

On the education and training front, the most important challenge is to substantially increase the allocation for education and training from 1.8% of GDP to 3.5% by FY2025.

Moving forward: On the education and training front, the most important challenge is to substantially increase the allocation for education and training from 1.8% of GDP to 3.5% by FY2025. Second, the money should be well spent with emphasis on education quality including physical facilities, emphasis on English, science and technology, and teacher training. Third, greater attention should be given to equity of public education spending. Fourth, the education management should be decentralised to the local government institutions with involvement of parents in decision making. Fifth, the University Grants Commission should be reformed and empowered to expand higher education through a judicious mix of public and private supply. Sixth, high priority should be given to the full implementation of the National Skills Development Policy. Involvement of the private sector in training through specialised as well as on-the-job training should be encouraged through regulations and incentives to make training demand driven.

Regarding social protection, the rapid implementation of the new NSSS is a top priority moving forward. This will modernise the social protection system of Bangladesh when fully implemented. It will not only provide publicly-funded income support to the poor and vulnerable at each stage of the life cycle, it will also introduce a system of social insurance financed both by public and private sector and linked to employment that will support the evolution of modern employment practices in Bangladesh.