Is Bangladesh Really Growing at 8% Plus Rate in Real Terms?

By

Introduction

According to Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Bangladesh gross domestic product (GDP) –which is the measure of economic activity across Bangladesh–has grown by 8.13% in real terms in FY19. On the basis of this estimation, the government is also projecting that the real economic growth will be 8.2% in FY20 and may even exceed the official target. This optimistic performance and outlook, however, does not go together with all other indicators of economic performance that are being produced by various other agencies of the government. This short note essentially concludes that Bangladesh economy must have slowed down significantly although it may be difficult to say by how much because of lack of timely national accounts data.

Areas of Concern

Below please find some of the areas of concerns that make professional economists and other observers skeptical about the real state of the economy.

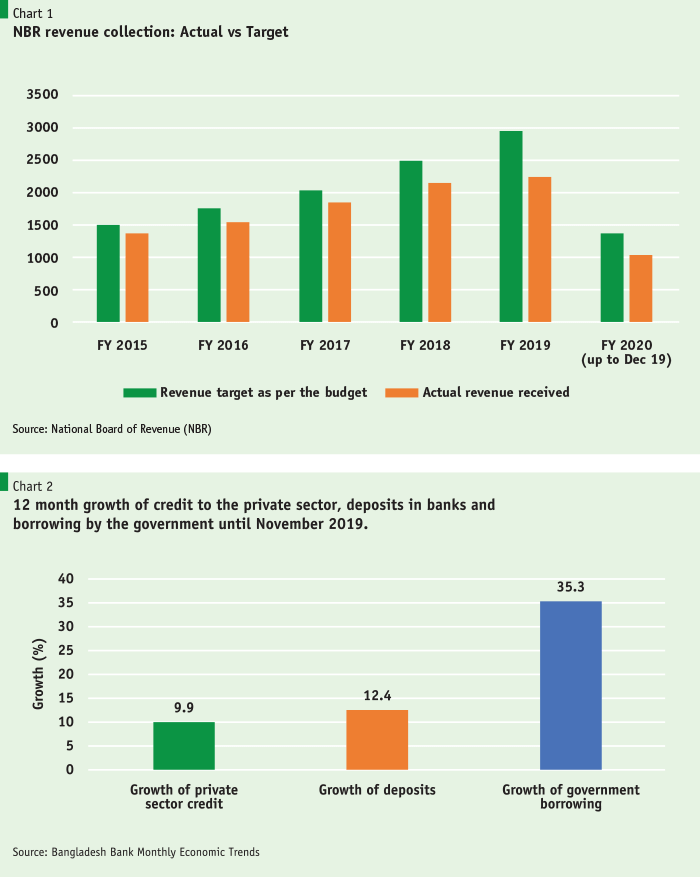

1. Revenue performance: It is widely expected that in a fast-growing economy tax revenue collection grows much faster than the nominal growth of GDP, particularly when the tax base is very narrow. This was also the case in Bangladesh until recent past, with NBR revenue growth rate significantly exceeding or at least remaining at par with the nominal GDP growth rate. However, last year (FY19) NBR revenue collection was about 10% well short of the targeted 35% growth rate. In the current fiscal year, the growth rate of revenues has decelerated further to only 7.39% in the first half of the year and the shortfall in NBR tax collection in the first half of the year is Tk. 31,000 crore. If manufacturing sector is growing at 18%-19% rate in nominal terms as per the national accounts projections, questions remain why would the domestic VAT collection be declining or not growing at all. Such inverse relationship between manufacturing growth and VAT revenue collection cannot be observed in any other country of the world. One would expect the VAT revenue collection to grow at least at the same rate as the manufacturing sector growth rate, but in reality VAT is declining or unchanged.

If manufacturing sector is growing at 18%-19% rate in nominal terms as per the national accounts projections, questions remain why would the domestic VAT collection be declining or not growing at all. Such inverse relationship between manufacturing growth and VAT revenue collection cannot be observed in any other country of the world.

2. Financial Sector Indicators: Financial sector indicators like credit expansion to the private sector, deposit growth rate, interest rate structure, profitability of banks in terms of return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE), state of health of the non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) does not give us any indication that the real economy is really expanding, let alone expanding at 8.2% rate or more. Credit expansion to the private sector has further declined to 9.9% in the 12-month period through end-November 2019 after declining to 11.3% in FY19. This is the lowest 12-month credit growth in at least more than one decade. Credit to the private sector is likely to decline further as government borrowing from the private sector is going to grow much faster due to the emerging record revenue shortfall.

Banking sectors capacity to lend is determined by its capacity to mobilize deposit growth. There was an expectation that deposit growth would pick up following the slowdown in sales of National Saving Directorate (NSD) instruments due to restrictions imposed and online verifications introduced recently. However, that did not happen to the extent expected. Deposit growth still remains subdued at 12.4% as of November 2019. This points to the suspicion that a significant part of financial savings not going to NSD instruments are remaining outside the banking system.

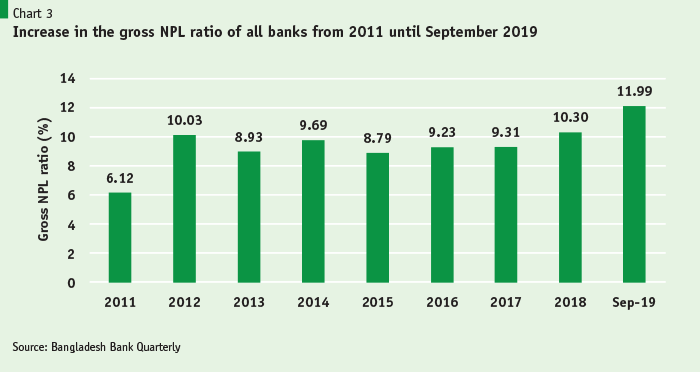

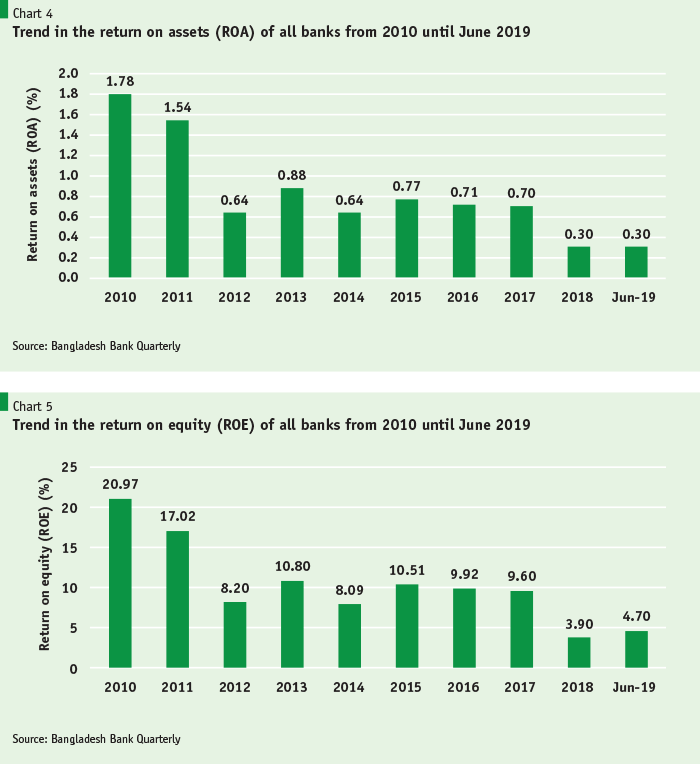

Furthermore, in a strong economy we should not expect the percent of nonperforming loans to hit almost 12% based on official Bangladesh Bank reports. As noted by IMF in its Financial Sector Study, the actual defaulted loans in Bangladesh is about 23-24% of the outstanding loans once we take into account the amounts already rescheduled and the amounts which are disputed and held up in the court system for a long time. This deterioration in the non-performing loans of the banking system and the reported weakening of the financial position of the corporate sector points to weakening of economic activity.

Financial position of the banking system has also weakened significantly in recent years. Return on Assets (ROA) of the banking system used to be quite respectable at 1.8% in 2010, but has steadily declined to 0.3% in June-2018 and remained at that very low level as of June 2019. Similarly, the rate of return on equity (ROE) for the banking system which was very respectable in FY10 at 21%, has also declined to only 3.9% in June-2018, and thereafter increasing slightly to 4.7% as of June 2019. The deterioration is most pronounced in state-owned commercial banks, where the ROE equity declined from 18.4% in 2010 to negative 12.3% in June 2018. Except for a few banks, most for most banks the ROAs and ROEs are extremely low, and in some cases negative. This decline in the efficiency of investment has also been reflected in the severe decline in stock prices of most banks in Bangladesh.

3. Government Borrowing and Crowding Out of private Sector: This is another emerging serious issue, which needs to be addressed immediately. This is the result of weak revenue collection which is a reflection of weak economy and absence of reforms in the areas of tax policy and tax administration including absence of modernization of revenue administration. The tax administration system that was put in place during British time is no longer applicable for today’s $300 billion economy. Bangladesh’s tax/GDP ratio at about 10% of GDP was always the lowest even when compared with sub-Saharan countries. In the last several years the ratio has been declining further and now it stands at below 9% of GDP. Certainly, Bangladesh cannot meet its development and SDG objectives along with the aspirations of the citizens for better services with such meager resources. Our neighbors India and Nepal collects almost twice the level of tax revenue compared with Bangladesh in terms of Tax/GDP ratio.

Because of the growing shortfall in revenue, the government has already borrowed Taka 48,015.81 crore by December 2019, the 1st half of FY20. Since execution of development plans picks up in the second half of the fiscal year, based on current trend, net domestic borrowing of the government may even cross Tk. 1.0 lac crores (or Tk. 1 trillion) in the current fiscal year. At the end of June 2019, the outstanding stock of government borrowing (net) was Tk. 1.08 trillion and by December 2019, the corresponding figure increased to Tk. 1.57 trillion. The increase in government credit (net) in the last 12 months through December 2019 was 59.8%. This figure is likely to approach almost 100% by the end of the current fiscal year. It is unthinkable that in one year, Bangladesh Government is going to almost double the stock of outstanding debt to the banking system. This never happens in a fast-growing economy. Only in a distressed financial position and when the economy is extremely weak that any government anywhere in the world goes for high level of bank financing and even under that situation doubling of its public debt (net) vis-à-vis the banking system in a reasonably stable macroeconomic environment is simply unheard of.

Bangladesh Government is going to almost double the stock of outstanding debt to the banking system. This never happens in a fast-growing economy. Only in a distressed financial position and when the economy is extremely weak that any government anywhere in the world goes for high level of bank financing…

Prudent fiscal management has been the hallmark of Bangladesh’s macroeconomic stability and keeping the deficit level below 5% of GDP has served as the anchor for sustained macroeconomic stability. This anchor is not going to remain in place if the government fails to boost up its revenue mobilization efforts through massive reforms.

4. External Sector Indicators: Export, Import, LCs Opened and settled, and reserve levels of Bangladesh Bank all point to a deteriorating external sector outcome and slowing down of the economy. In a fast-growing economy imports should be surging, but in Bangladesh import growth has been negative 5.3% in the first five months of FY20. Import contraction has been the most pronounced in November 2019, the most recent month for which data is available. Looking forward, the outlook appears to be even grim as the spread of corona virus in China has virtually stopped all kinds of trade between China and Bangladesh. The effect of this phenomenon will be reflected in the import and customs duty data for the month of January and onwards.

Based on LC data reported by Bangladesh Bank, LCs opened in the July-November period declined by 9.9%. It is even more concerning that LCs opened for industrial raw materials declined by more than 19% which shows the current state of industrial capacity utilization. Since LC opening is a forward looking indicator, this sharp decline in import of industrial raw materials pointing to a further weakening of industrial production in the coming months.

The picture on the export side is equally depressing. Export growth in first seven months of the current fiscal year (through January 2020) has declined by 6.8% compared with 13.4% growth recorded during the corresponding 7-month period in the preceding year. As a matter of fact, the slowdown in exports already started in January 2019 when exports grew by less than 8%. All major categories of exports including RMG experienced significant contractions in export. Inflow of workers’ remittances is the only bright spot recording about 21.5% growth in the July to January period. After several years of virtual stagnation and an up and down pattern, remittances may be on its way to cross $18-19 billion for the first time.

Slowdown in global economic and trade—in part also due to trade related tensions between the US and China, and US and the EU–have contributed to slower export growth for most of the comparator countries. However, the slowdown in the case of Bangladesh is more pronounced than its comparator countries. This markedly sharper decline of Bangladesh’s exports coupled with the appreciation of Bangladesh Taka viv-a-vis the US dollars and comparator countries point to loss of export competitiveness for Bangladesh exporters.

Despite the contraction of imports and the surge in remittance flows, the external current account still remains in significant deficit ($678 million in the first quarter), contributing to a corresponding reduction in the gross official reserve level to $31.7 billion in mid-November. The moderate decline in gross official reserves coupled with increased imports of goods and services have reduced the import coverage of official reserves to less than 6 months, compared with more than 8 months of reserve coverage at its peak.

5. Corona virus is likely to dampen Bangladesh’s growth outlook further. China is the manufacturing hub of the world and like every other country will also impact Bangladesh. China is the largest import sourcing country for Bangladesh with 27% of Bangladesh imports originating from China, and a large part of that are intermediate goods for further processing to meet export and domestic demand. In particular, woven garment export is heavily dependent on import of manmade and fine fabrics from China and the sourcing cannot be easily shifted any other country at prices which are competitive with China. In addition, for a range of electronic components, auto parts, basic ingredients for the pharmaceutical industries, intermediate products for light engineering, and a whole range of other intermediate and finished products Bangladesh is largely dependent on China. A large number of small and medium importers are make their living by importing consumer products by visiting China and placing orders during their visits. All these imports and visits are completely shut down since January till end-February and there is uncertainty about the duration of this crisis. There will also be significant impact of these developments on tax revenue collection of the NBR which is already performing badly. The effect of corona virus on tax collection will be felt from March onwards after allowing for the time lag due to shipping from China. There is no estimate for such revenue loss at the moment, but undoubtedly it will be quite significant and would accentuate the challenges for fiscal management.

6. International Environment: Global economic environment is not favorable at present as it is clouded by the slowing of the major economies like Germany, China, Japan and India. The ongoing trade tensions between China and the USA and the new ones between the USA and the EU and USA and India are also undermining the outlook for a speedy pick up in international trade. Bangladesh’s competitors (like India, China, Indonesia, and Pakistan) all have depreciated their currencies significantly against the US dollar in recent months. At the same time, Bangladesh Bank has been maintaining the exchange rate virtually unchanged (with very minor depreciation) primarily through administrative controls and interventions in the interbank market to support the Taka. We are moving against the global tide and we are not using a potent instrument like the exchange rate policy to support our exports in this difficult global economic environment.

We are moving against the global tide and we are not using a potent instrument like the exchange rate policy to support our exports in this difficult global economic environment.

Since January 2020, the global economic environment has been badly hit by the rapidly spreading corona virus across the globe. Much of China has been locked down for more than 6 weeks and many cities in Korea, Iran and Italy have also been locked down to stem the propagation of this deadly virus. Global stock markets are only very recently factoring in this risk into stock prices as the Dow-Jones stock index declined by more than 1,000 points or more than 3% on January 24, 2020. Already many automobile factories of Toyota, Hyundai, and even GM are temporarily shutting down due to shortage of parts. As the global value chain is integrated—be it automobiles, electronic goods including products like iPhone–for most manufacturing products including, the whole global production system is coming under stress. Even before the spread of the virus to Korea, Italy and Iran, it was estimated that the Chinese economic growth will come down by 2 percentage points to 4%-4.5%, with global economic growth decelerating by 0.3%. Now, with the direct impact spreading to more than 20 countries and increasing every day, global economic impact is likely to be much higher than envisaged earlier.

Concluding Observations:

Data from all segments point to the direction that the real economy in Bangladesh must have slowed down. This is nothing unusual, because most economies in the world have been experiencing a slowdown in growth, as indicated in the IMF World Economic Outlook report. For every country, real GDP growth in 2019 was estimated to be slower than 2018 and the outlooks for 2020 are projected to much worse than those of 2019.

This IMF outlook was prepared in the context of the October World Economic outlook, well before the spread of Corona Virus from China and which has also impacted more than 20 other countries. China being the largest global industrial base and the center of global value chain, both global output and global trade will be further dampened in the coming months. The extent of the damage to global output and trade due to corona virus will depend on how soon the ongoing epidemic is contained and the travel restrictions to and from China are restored along with return of normalcy in China.

Against this environment there is a serious need for reevaluating Bangladesh’s real economic growth projection for FY20 and beyond. This is very important for the reason that the government is in the process of preparing the Eighth Five Year Plan and the Perspective Plan for 2041. The macroeconomic projections for these medium and long-term exercises will require better understanding of the current economic situation. Since Bangladesh does not prepare quarterly GDP projections, what was assumed to be the outlook at the time the budget for FY20 was prepared in April-May 2019, may have changed significantly. In the absence of such a fundamental review, question will arise whether Bangladesh authorities are in a state of complacency and building a sand castle for the coming years? If anything, we should look at India and try to understand why its growth rate has suddenly collapsed from more than 8% to only 4.5% in the most recent quarter. The collapse in the Indian growth rate from 6.8% in 2018 to 4.5% or so in 2019 is primarily attributable to problems associated with housing and financial sector. It is noteworthy that despite the somewhat favorable outlook projected by IMF for India in the recent WEO exercise, more recent projections point to a very modest recovery of the Indian economic growth to 5%-5.8% for 2020. Many Indian and foreign analysts are even questioning whether India will be able to come out of this diminished growth outlook anytime soon or whether it has gone back to its old “Hindu Growth rate” of 3%-3.5% for years to come.

Bangladesh government must question the BBS data on real GDP and have a reality check vis-à-vis all other indicators, as discussed above. The reviews of national accounts data compilation should be transparent and accurate for the data to be accepted as credible. Otherwise, investors and analysts will not take government figures seriously and government’s policy response will be wrong. One practical suggestion is also to undertake efforts to compile quarterly GDP data and publish those regularly. The long lag in compiling national accounts data is contributing to information vacuum regarding what is happening in the real economy over the course of the fiscal year, preventing timely policy response from the authorities. Bangladesh economy may have already slipped into a big hole, which we must avoid before it is too late.