State of the Bangladesh Economy 2019

By

The 2019 backdrop

Good news is seldom news. Bad news hogs headlines. For Bangladesh economy, the year 2019 is closing with a mix of good and bad news. Most external observers of Bangladesh economy have been generally effusive in acknowledging the progress achieved in economic and human development aspects with notable decline in poverty. That the economy is growing at a record pace is now recognized by our leading development partners, namely, the World Bank, IMF, ADB, all of whom projected GDP growth rate for FY2019 very close to the official figure of 8 per cent. Remittance inflows could top $20 billion for the first time in FY2020 while FDI is finally showing signs of traction having reached $3.9 billion in FY19 (up 50%) with several promising investments in the pipeline in power and infrastructure sectors.

Lest this lull us into complacency, the challenge now is to sustain growth in the face of mounting challenges. These challenges multiply as we head into the years when the economy graduates out of LDC status and starts losing preferential market access for our exports unleashing stiffer competition in the world market. In the medium term, our economy will need to become more competitive and productive by rapidly developing our human capital and infrastructure, institutional and regulatory capacity that will reinvigorate our investment and, very importantly, provide productive jobs. In recent years, Labor Force Survey data of 2013 and 2017 suggest that there has been a marked decline in job growth and especially in manufacturing, where there has been an absolute decline in the number of employed.

But beyond these significant medium-term challenges, a downward movement in a number of short run-indicators points to challenges that need to be addressed immediately. These include our mixed export performance in the past year, recording 11% growth in FY2019 but slowing down to negative 5.8% growth in the first half of FY2020. In parallel, imports have also declined, and quite sharply so in the case of capital machinery and intermediate goods pointing to a slowdown in investment and manufacturing activity.

On the domestic front, a sharp drop in revenue growth in the first four months to less than 5 percent, is significantly lower than trend growth rate and far lower than the annual target of a 40 percent increase. The shortfall in revenues has been accompanied by a sharp increase in government borrowing from the Banking system, to a point when the Government has almost entirely exhausted in the first four months its annual bank borrowing target. These high public sector borrowing requirements have contributed to keeping interest rates high and lowering credit growth to the private sector. In the first half of FY2020, credit to the private sector has grown by less than 10 percent, highly incommensurate with the expected nominal GDP growth of about 13.5 percent. These factors, together, raise alarms about the capacity of the budget to finance our development objectives; equally importantly, they raise the specter of fiscal and monetary instability. Combined with this, the past year has experienced a host of adverse developments in the financial sector with mounting non-performing loans, slowdown in deposit growth in banks, and liquidity constraints resulting in anemic growth of private credit, — the combined outcome of the widely recognized deterioration in financial sector governance. Sound policies and actions are needed to prevent the financial sector from becoming the Achilles heel of an otherwise dynamic economy, but one that is facing many challenges.

On the external front, vulnerabilities and uncertainties in the world economy appear ascendant with the sinister rise of economic nationalism, unilateralism, and protectionism in those countries that were the original protagonists of free trade and globalization.

A cursory assessment of geo-economic and geo-political events of 2019 shows formidable challenges appearing on the 2020 firmament. The outlook is for anemic global growth for another year – so-called “new normal” — with strong headwinds on the trade front prompted by two major disruptive events – US-China trade war and the deliberate undermining of WTO by rendering dysfunctional its Dispute Settlement Appellate Body – the so-called “crown jewel” of the multilateral system. By any measure Bangladesh has been a significant beneficiary of the multilateral system and stands to lose if the new world order of international trade is overtaken by regionalism, bilateralism, and unilateralism.

At home, we expect the launch of an ambitious 8th Five Year Plan (FYP) in the second half of 2020 (FY2021) with the momentous challenge of sustaining 8%+ GDP growth which will need, among other things, stronger efforts at leveraging the opportunities presented by the vast global marketplace on the one hand and harnessing the potential of the demographic dividend at home. This will happen as the countdown to Bangladesh’s graduation out of LDC status in 2024 begins, and the phasing out of International Support Measures sounding alarm bells of “preference erosion” are heard loud and clear. Our preparedness for this eventuality – coveted as it is – will be put to the test. Given this evolving cornucopia of events, sustaining our growth momentum with social inclusion and robust job creation will be the heightened challenge facing the nation in the coming year. To make our future brighter than the past, a business-as-usual approach will no longer be an option.

Growth performance in retrospect

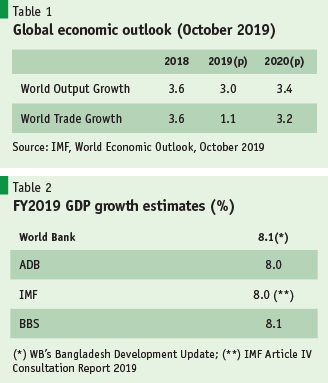

The Bangladesh economy in 2019 continued to demonstrate remarkable resilience and strength amidst a significant decline and uncertainty in global economic conditions. In the last three years, gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates have comfortably exceeded 7 percent p.a. and touched 8 percent in fiscal years 2018 and 2019. This performance puts Bangladesh among the top ten fastest-growing countries globally. According to the BBS estimates, in 2019 per-capita income measured in nominal dollars was US$1,909 or 20 times what it was at independence. Bangladesh has been a lower-middle-income country under World Bank classification since 2015. Bangladesh’s impressive growth performance is taking place at a time when, according to the latest IMF estimates, about 90% of the world economy is facing a significant slowdown in growth. Overall global economic growth rates are now predicted to be 3% in 2019 instead of the 3.9% forecasted a few months ago.

On the demand side, public investments, a revival of export growth, and private consumption boosted by healthy remittances have been the leading contributors

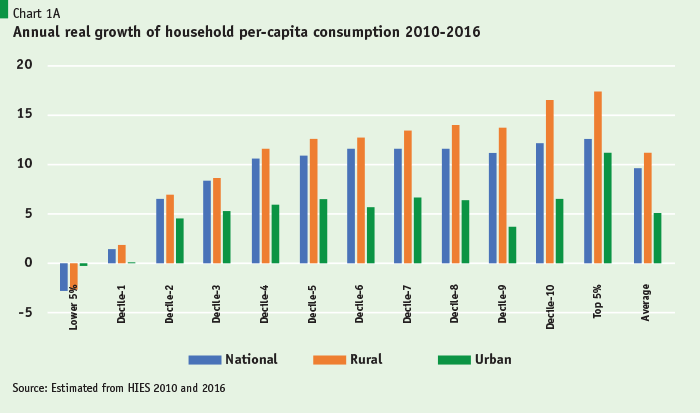

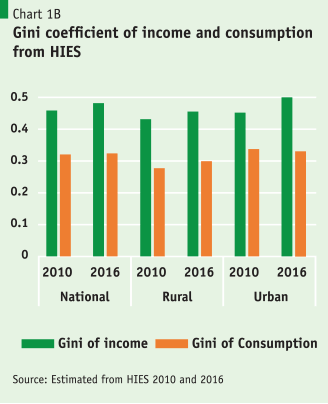

The sources of growth in Bangladesh are well balanced and diversified. On the production side most of the growth has come from manufacturing, especially large-scale manufacturing, services, and agricultural recovery. On the demand side, public investments, a revival of export growth, and private consumption boosted by healthy remittances have been the leading contributors. Because the sources of growth have been diversified, the benefits of growth have also been spread widely. Household surveys of consumption, which are a far more robust and reliable measure than household income, show household consumption per capita has grown, since 2016, at a robust rate of 9 percent per annum driven by a nearly 13 percent growth in rural per capita household consumption (Chart 1a). Moreover, almost all deciles, but the lowest, show significant growth of consumption, especially in rural areas. Thus, while the pattern of consumption growth across income groups is more markedly skewed towards the wealthier households and the bottom five percent of households have lost ground as reflected through a decline in real consumption per capita, growth has otherwise been well spread. And, as in the case of income, rural household consumption growth has been markedly higher than urban households. However, despite the skewness in consumption growth, the consumption Gini coefficient (Chart 1b) indicates that at the national level consumption inequality has been relatively stable and low at 0.32.

Bangladesh has made significant progress under the 7th Five Year Plan (FY 16 – FY 20) where the current fiscal year is the last year. Bangladesh’s achievements in accelerating growth, widely sharing its benefits, and its investments in human capital and infrastructure has meant that many of the goals of the 7th Five Year Plan have been achieved. According to official statistics, average economic growth in the past four years has been 7.6 percent, comfortably exceeding the plan target of 7.4 percent p.a. While it is not possible to precisely gauge the decline in poverty reduction during the plan years in the absence of recent surveys, the 2010 and 2016 surveys tell us that extreme poverty declined significantly from 17.6 percent 2010 to 12.9 percent in 2016. Similarly, significant gains in increasing Bangladesh’s installed power generation capacity, including captive power and renewable energy, to 21,419 MW representing more than a 25 percent increase in installed capacity comfortably meeting 7th plan targets. Similarly, in the road sector recent data suggests that the target of constructing more than 340 kilometer of four lane roads is likely to have been met. In human capital development, too, Bangladesh has largely achieved the quantitative goals of the 7th FYP in terms of achieving nearly 100 percent enrollment rates and gender parity in primary education. The newly released World Bank’s Human Capital Index 2018 report also showed Bangladesh to be among the best-performing South Asian countries well ahead of India and Pakistan by various measures of human development.

Bangladesh is now preparing the 8th Five Year Plan (FY 21 to FY 25) at an important cusp in its development journey. It has now officially started the United Nations’ graduation process out of the least developed category towards becoming a “developing country” in 2024. However, Bangladesh is still in the early stage of development. The critical challenge for Bangladesh will be to sustain the current high growth and even accelerate it to 9-10 percent per annum if it is to reach its objective of becoming a developed country by 2041. However, even sustaining the 7 to 8 percent rates of growth will be quite a remarkable performance that will require diversifying the economy in terms of its products, services, trading partners, while continuing to diversify agricultural produce into higher value-added crops. Achieving all this will require strong institutions and urban centers that can host manufacturing and service activities. And high growth will have to come on the back of robust export performance by leveraging the vast global market, No country in history has achieved sustained high growth by simply relying on the domestic market – neither China nor India, nor the dynamic East Asian economies.

As the Planning Commission’s Mid-Term Implementation Review (MTIR) of the 7th FYP has pointed out there is some bad news on the employment front. First, it appears that employment growth targets have not been achieved. Not only have the ambitious goals of creating 12.9 million jobs over the plan period — which includes two million foreign jobs — not been achieved there are signs of a significant slowdown in most sectors targeted for job growth. Whereas the 7th FYP had targeted increasing the share of manufacturing jobs from 15% to 20%, initial indications are the number of manufacturing jobs have actually declined.

Another related area where the achievement of targets has fallen behind is in international trade and export performance. The 7th FYP had envisaged exports increasing to US $47.5 billion by FY19, with export-GDP ratio of 16% and trade-GDP ratio of 36%. Actual performance in the external sector has been lagging behind target in all of these indicators due mainly to weak performance of exports in the years preceding FY19, though export growth was a decent 11% in FY19 at $40 billion. With exports showing a declining trend (-7%) in the first quarter of FY20, it is likely that 7th FYP target of average 12% export growth will be missed, unless there is a sharp pick up over the next eight months. As will be shown later, the exchange rate management has left much to be desired. It is our assessment that both RMG and non-RMG exports are constrained by the sharp rise in real effective exchange rate (REER). Compounding the exchange rate disadvantage is the anti-export bias of our protective tariff policies. By markedly raising the relative profitability of domestic sales over exports for most manufacturing products, Bangladeshi industrialists outside the RMG sector have little incentive to export. Thus, Bangladesh’s exports and economy continues to remain undiversified and vulnerable.

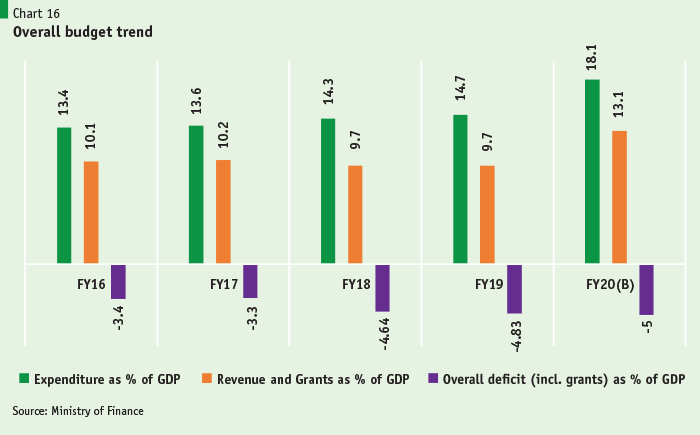

Finally, there remain significant constraints on the supply side. Despite marked improvements in power supply, the overall situation in infrastructure and trade logistics remain a constraint to Bangladesh’s growth prospects. As the MTIR accurately points out, Bangladesh’s ranking in infrastructure remains extremely low. This low rank in infrastructure is unfortunately further reinforced by low rankings of Bangladesh’s investment climate in the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI). Finally, according to the GCI Bangladesh also ranks very poorly in the education and skilling of the labor force. In all these three areas, Bangladesh ranks among the bottom fourth of countries. Long term growth to a higher middle-income developing country will not be possible unless Bangladesh urgently strives to improve the situation in these areas.

The Global Outlook

According to the IMF’s October 2019 World Economic Outlook, the world economy is now passing through “a synchronized slowdown.” More than 90% of the world economy is now seeing a deceleration in growth rates. Except in sub-Saharan Africa, more than half of the countries are expected to grow lower than their median rate in past 25 years. The IMF’s latest WEO report has continued with the recent tradition of revising global growth projections a notch downward from its previous projection — now projecting 3% output growth for 2019 against the earlier forecast of 3.9% — the lowest since 2009 (Table 1). This deceleration reflects carryover from broad-based weakness in the second half of 2018, followed by a mild growth uptick in the first half of 2019 that was supported, in some cases, by more accommodative policy stances. Trade growth continues to lag behind output growth – a new phenomenon of the post-financial crisis global economy.

Global economic slowdown is the result of weaker macroeconomic conditions in Germany and Japan, and largely because of idiosyncratic factors in a group of key emerging market economies such as Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, India, and Russia. These include a slowdown in domestic demand in India; a softening in China’s growth because of the US-China trade war.

The global trade growth, after peaking in 2017, slowed considerably in 2018 and the first half of 2019 and is projected at 1¼ percent in 2019. The slowdown reflects a confluence of factors, including a slowdown in investment, the impact of increased trade tensions on spending on capital goods (which are heavily traded), a tech cycle, and a sizable decline in trade in cars and car parts. Global trade growth is projected to recover to 3.2 percent in 2020 and 3.75 percent in subsequent years. However, there is considerable uncertainty concerning the future structure of value chains and the wider repercussions of US-China trade tensions that could weigh on trade growth.

Emerging and Developing Asia remains the main engine of the world economy, but growth is softening gradually with the structural slowdown in China, which was contributing as much as 30% to global growth. Output in the region is expected to grow at 5.9 percent this year and at 6.0 percent in 2020, posting a sliver of optimism about the future.

In recent years, uncertainty has gripped the world economy leading to significant diminution in cross-border investment flows and adding to vulnerability. This weak and vulnerable world economic conditions means that downside risks have become much more important for the Bangladeshi economy. Both export demand and remittance flows may be adversely affected.

In recent years, uncertainty has gripped the world economy leading to significant diminution in cross-border investment flows and adding to vulnerability. This weak and vulnerable world economic conditions means that downside risks have become much more important for the Bangladeshi economy. Both export demand and remittance flows may be adversely affected. On the other hand, the slowdown in Chinese exports may provide opportunities for Bangladesh to increase their market share in the US and EU markets. However, to avail of these opportunities Bangladesh will need to become more competitive and investment friendly for both domestic and especially foreign investors. Foreign direct investment is one area in which Bangladesh lags behind countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand. The need to increase investment and competitiveness is a theme that will recur in the following sections.

Growth and macroeconomic outlook

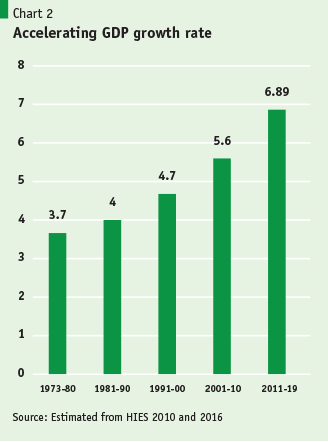

Bangladesh economy’s growth has been steadily accelerating over the decades (see Chart 2) allowing the 7th FYP to set a growth target of reaching 8% in FY20. After exceeding above 7% GDP growth rate for three consecutive years it crossed 8% in FY2019 for the first time despite the global trade war and the looming threat of Brexit. The latest official statistics on national accounts for FY2019 estimated by BBS reveals the GDP growth rate for FY 19 to be 8.1 (provisional).

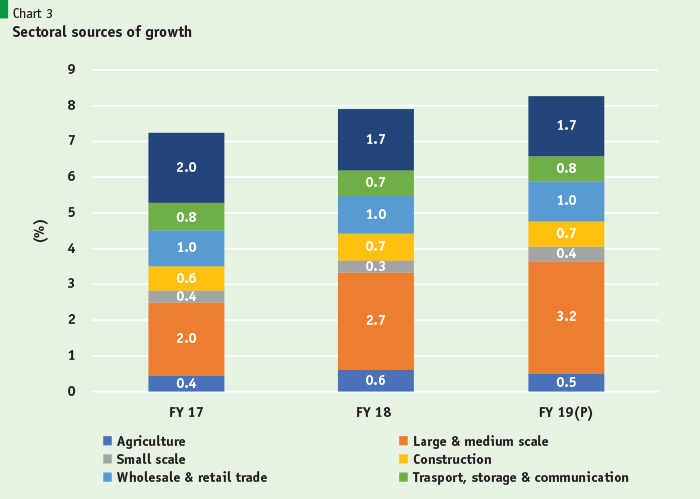

This growth acceleration reflects better performance in manufacturing, and service sector compared to previous year. No major natural calamity led to a reasonable growth in the agricultural sector. The significant growth in the manufacturing sector was the key to the overall robust growth for FY19 (Chart 3). The growth in manufacturing sector clocked over 14% as compared to last year’s 13.4%. Rise in export growth (11.5%) in RMG sector, improved energy supply and relatively stable political situation helped the increase in output of the large and medium industries (15%) in the manufacturing sector. Wholesale and retail trade, construction were other major contributors to growth.

There are controversies around growth numbers. Take for instance, the growth rate of 8.1 percent was based on an estimated, sizzling 14 percent growth of large and medium manufacturing enterprises. Record growth of the large-scale manufacturing sector has been met with skepticism by most observers of the Bangladesh economy. Then there are other indicators that are inconsistent with this high growth rate. Chief among these are: the weak private investment growth rate; the startling decline in credit growth last year and in the first half of FY19; and the extremely low rate of revenue collection despite robust manufacturing growth. Financial indicators—which are harder numbers and more reliable—are not moving in line with the officially recorded growth in GDP.

Despite these issues, few will contest that Bangladesh is a rapidly growing economy. With an ICOR (incremental capital-output ratio) of 4.3 and investment rate of 31.5% of GDP, it still yields a GDP growth rate of 7.3%, which by international standards is an excellent rate of growth. Bangladesh’s international development partners have also recognized the high growth performance of Bangladesh in their growth projections (Table 2). After a decade of under-projecting Bangladesh’s GDP growth, they have come to realize that estimating GDP and its growth rate can only be done (following internationally accepted cross-country comparable UN System of National Accounting) by the official statistical agency, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), despite all the flaws. Though GDP growth projections by international agencies hog headlines, at the end of the day, researchers, analysts, academics, and development partners, all have to use the official growth figures generated by BBS. The national statistical agency needs technical support to build capacities and improve statistics going forward.

The major challenge ahead of Bangladesh now is to sustain and even accelerate its growth rates. Looking at growth momentum in the 21st century and assessments of many analysts and observers of the Bangladesh scene, it would be reasonable to surmise that the economy is moving closer to a take off stage, though yet an LDC. The critical challenge for Bangladesh will be to sustain the current high growth and even accelerate it to 9-10 percent per annum if it is to reach its objective of becoming an Upper Middle-Income Country by 2031 and a developed country by 2041. However, even sustaining the 7 to 8 percent rates of growth will be quite a remarkable performance that will require diversifying the economy in terms of its products, services, trading partners, while continuing to diversify agricultural produce into higher value-added crops. Achieving all this will require strong institutions and urban centers that can host manufacturing and service activities. It will require sound governance, financial and regulatory policies to raise savings and attract investment, especially foreign direct investment that has been considerably lacking in Bangladesh compared to its competitor countries in Southeast Asia. Finally, it must be acknowledged that such high growth rates can only be achieved on the back of robust export growth by leveraging the vast global economy. No country in history has achieved 8%+ growth rate by relying on the domestic economy – neither China, nor India, nor South Korea.

Savings-Investment Scenario

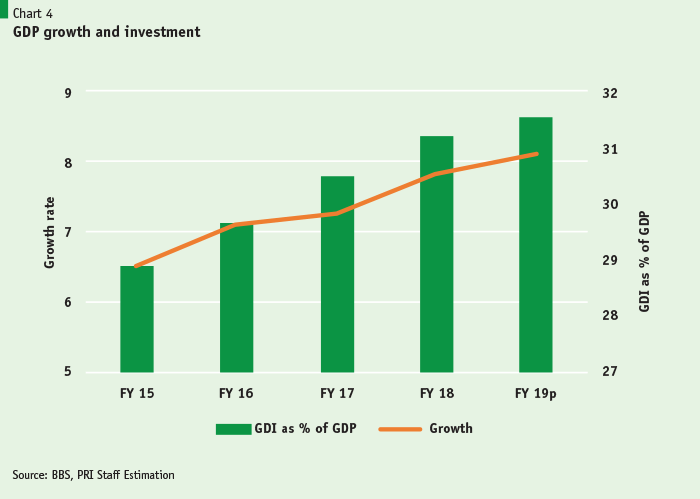

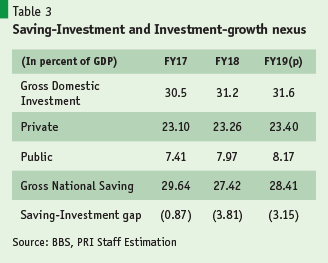

Sustaining Bangladesh’s high growth rate will require significantly raising Bangladesh’s savings and investment rates and ensuring the quality of the public investment program. Thanks mainly to a significant surge in public investment, investment rates in Bangladesh has exceeded 30 percent of GDP for three consecutive fiscal years (Table 3 and Chart 4)  The annual public investment program has quadrupled in the last 10 years since the current government took office and as a result, despite a stall in private investment rates overall investment has increase by 3 percentage point of GDP in the last five years and the investment to GDP ratio now nearly touches 32 percent. Seven mega development projects by the government are well underway. These public projects are expected to have significant positive impact on future economic activity if properly implemented. The projects are the Padma Bridge, Rooppur Nuclear Power project, Paira Sea Port, the coal fired large power projects of Matarbari and Rampal, Metro Rail and LNG terminal. The LNG terminal at Maheshkhali has already started operating. Of these mega projects the government has allocated Tk 14,980 crore for the Rooppur Nuclear Power plant project, Tk. 5,360 crore for the Dhaka Metro Rail Project and Tk 5,370 crore for the high priority mega project, Padma Bridge, in the current fiscal year. Moreover, the government recently approved two more Metro Rail projects of estimated worth Tk 93,800 core and also allocated Tk 2,750 crore for Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport expansion project. The progress in physical completion of these projects is expected to boost investor confidence.

The annual public investment program has quadrupled in the last 10 years since the current government took office and as a result, despite a stall in private investment rates overall investment has increase by 3 percentage point of GDP in the last five years and the investment to GDP ratio now nearly touches 32 percent. Seven mega development projects by the government are well underway. These public projects are expected to have significant positive impact on future economic activity if properly implemented. The projects are the Padma Bridge, Rooppur Nuclear Power project, Paira Sea Port, the coal fired large power projects of Matarbari and Rampal, Metro Rail and LNG terminal. The LNG terminal at Maheshkhali has already started operating. Of these mega projects the government has allocated Tk 14,980 crore for the Rooppur Nuclear Power plant project, Tk. 5,360 crore for the Dhaka Metro Rail Project and Tk 5,370 crore for the high priority mega project, Padma Bridge, in the current fiscal year. Moreover, the government recently approved two more Metro Rail projects of estimated worth Tk 93,800 core and also allocated Tk 2,750 crore for Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport expansion project. The progress in physical completion of these projects is expected to boost investor confidence.

A focus on Growth Challenges

In the near term, the current sources of growth, which is a combination of growth in private consumption and in public investment can continue to support a high growth rate of about 7% in the next few years. However, such a pattern of growth is not sustainable even over the medium term for a developing country. To sustain and accelerate growth, investment rates, and productivity and competitiveness has to be raised. Three main investment policy challenges need to be addressed. First, investment rates need to be increased markedly by about seven to eight percentage points to stimulate private investment rates including foreign direct investment. Private investment rates have been relative stagnant at about 23 percent of GDP for the past few years. Future growth will become more capital intensive as investment in urban development increase with more technological sophistication. Thus, in order to maintain growth and accelerate it to close to 10 percent, private investment rates will need to grow by six or seven percentage points of GDP over the next 20 years. Moreover, most of these increase in private investment rates ideally should come from foreign direct investment. Compared to the foreign investment rates of 8 to 9% of GDP in the Southeast Asian countries, Bangladesh gets relatively puny percentage of its GDP in FDI. This is a critical constraint as FDI not only brings finance or investment, it also brings linkages to regional and global value chains, access to technology and markets without which the economy cannot be diversified.

The second major challenge in investment will be to ensure the quality of the public investment program. Although public investment rates have increased markedly, as noted above, the quality of investments and value for money will need to be ensured. Mis-procurement from non-transparency bidding and contracting, delays and implementation, inattention to environmental and social safeguards, will all mean that the returns from public investment will be lower than expected. Given the rapid rise of public investment, building the capacity of the institutions to ensure a high-quality public investment program has become critical. Part of ensuring high quality public investment program will be ensure that adequate operations and maintenance arrangements are made so that public infrastructure do not depreciate quickly.

The third major challenge will be to raise national savings which includes remittance of migrant workers. This will be essential to achieve higher investment and consequently higher economic growth. Bangladesh’s performance here is already quite remarkable and close to the station standards. The gross national savings rate has substantially improved to 28.4 % of the GDP as compared to last year’s 27.42% which helped meet the much-coveted goal of over 8% GDP growth in FY19. The negative gap between savings and investment in FY19 is a reflection of investment exceeding savings and shows up as current account deficit in the balance of payments, after many years of current account surpluses and under-investment since 2001.

All of this growth impetus must happen as trade openness intensifies and Bangladesh economy gets more integrated with the world economy through trade. Trade-led growth, based on leveraging the vast world economy, is the only way to achieve the kind of rapid growth that we desire in future.

Employment and Wage developments

Unfortunately, Bangladesh’s acceleration of growth rates has not been reflected in job markets. The evidence suggests that both job growth and wage growth have slowed down markedly. By adopting a labor-intensive and manufacturing-export oriented growth strategy, Bangladesh has been an impressive performer among developing countries in creating jobs which grew at a rapid rate of about 2.4 percent until recently. As a result, the economy has been able to provide almost 61 million workers with jobs at present. Furthermore, most of the job growth between 2003 and 2013, 10 million out of 14 million, has taken place in higher productivity manufacturing and construction industries and services. This drawing of the workforce out of agriculture had led to a significant rise in rural real wages and incomes and lowering of poverty. Socially, the 2-3 million female workers employed in most ready-made garments manufacturing has been critical in raising female rights and empowerment and its many associated benefits.

But significant challenges are looming. Bangladesh needs to generate close to 2 million jobs every year to accommodate new entrants to its labor force. Further, 40 percent of workers are still in agriculture where the share of GDP is only 13 percent. About 85 percent of the workers work in informal jobs, 2.7 million labor are unemployed and another 6.6 million of workers are currently underemployed.

In this backdrop, a serious development is the halving in employment growth between 2010-2013 and 2013-2017 from 2.4 percent to 1.2 percent p.a. It is worth noting that the Labor Force Survey of 2017 which provides these results will need scrutiny, but the initial findings are dramatic. In urban areas and industry, job growth has slowed down from about 8 percent p.a. in the first period to about 1 percent p.a. in the most recent period. Even more dramatic, according to BBS, total employment in the manufacturing sector between 2013 and 2017 fell in absolute terms from 9.5 million to 8.7 million. This suggests that, despite adding more than Tk 450 billion-worth of output (in real terms using 2005–2006 prices), employment shrank by close to 1 million. Such developments are corroborated by trends in relative wages – which show that manufacturing-agricultural or urban rural nominal wage premiums are only about 38 percent. Real differences will be considerably less. If correct, then it will suggest a slowdown in urban development and structural transformation of the economy. Clearly, more policy and research attention are needed on this issue.

Monetary Developments: Inflation, Monetary Policy and Banking

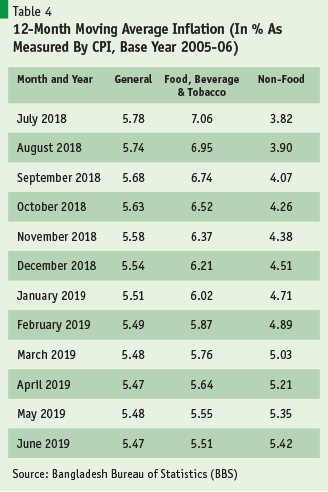

Inflation has been well contained. Overall year-end general (12 month moving average of) consumer price index inflation rates in June 2019 remained at 5.5%, within the Bangladesh Bank’s target of 5.6% for FY19. However, opposing trends were observed between the prices of food, beverage and tobacco, and those of non-food items. Whereas the 12-month moving average inflation of food, beverage and tobacco fell from 7.1% in June 2018 to 5.5% in June 2019, that of non-food items increased from 3.7% in June 2018 to 5.4% in June 2019 (See Table 4.). Increased flow of imports, better harvests and open-market sales by the Government helped to keep food prices within an affordable range contributing to this downward trend. However, the recent decision by India to ban exports of onions, in order to maintain adequate domestic supply in that country thereby lowering prices, has led to the price hike of onions in Bangladesh, prompting importers to look for alternative sources like Myanmar, Egypt, China and Turkey. It is hoped that after the imports from these new sources reach the market, the prices of onions will stabilize.

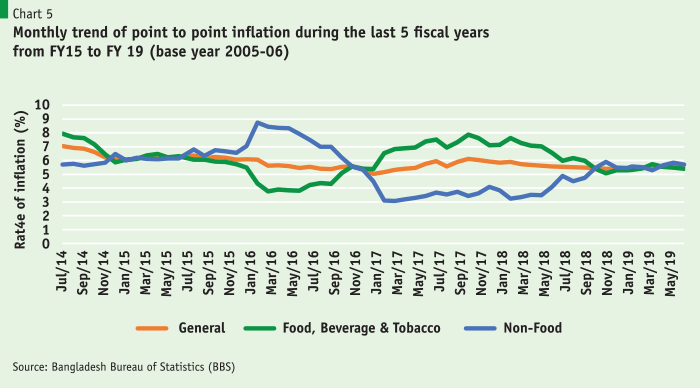

Point-to-point inflation remained within a constant range throughout the year and fell only slightly from 5.54% in June 2018 to 5.52% in June 2019 (Chart5). The rate of food inflation rose slightly to more than 6% towards the beginning of FY19, but fell gradually throughout the rest of the year, from 5.98% in June 2018 to 5.40% in June 2019. The rate of non-food inflation rose steadily throughout the year, from 4.87% in June 2018 to 5.71% in June 2019. The inflation of clothing and footwear started high during the first half of FY19, but declined markedly during the second half, from 10.01% in June 2018 to 5.94% in June 2019. The rate of inflation of gross rent, fuel and lighting more than doubled, from 1.91% in June 2018 to 4.82% in June 2019. Furniture, furnishing, household equipment and operation witnessed steady, yet small, increases and decreases in their rate of inflation throughout the year, finishing slightly higher from 7.46% in June 2018 to 7.73% in June 2019. After a slight increase for most of FY 19, the rate of inflation of medical care and health expenses saw a decline in the second half, to finish slightly higher, from 2.20% in June 2018 to 2.93% in June 2019.

Monetary Policy accommodative but Monetary Outcomes restrictive

The monetary and banking sector perhaps pose the most important near-term policy challenges for Bangladesh. These include a marked decline in broad money (M2) growth and private sector credit growth, accelerating public sector borrowing and the rise of high cost savings certificates. Monetary policy has generally been accommodating with a lowering of policy rates and a high growth (16%) in reserve money until May, with a sharp deceleration to 5.8% in June, at year end. Aiming to reduce risks, Government announced the policy of reducing the advance-deposit ratio from 85 percent to 83.5 percent in 2018, enforcement was delayed, and the measure ultimately cancelled in September 2019. Accommodating policy measures were also accompanied by directives to Banks to lower interest rates to single digits (i.e. 9 percent).

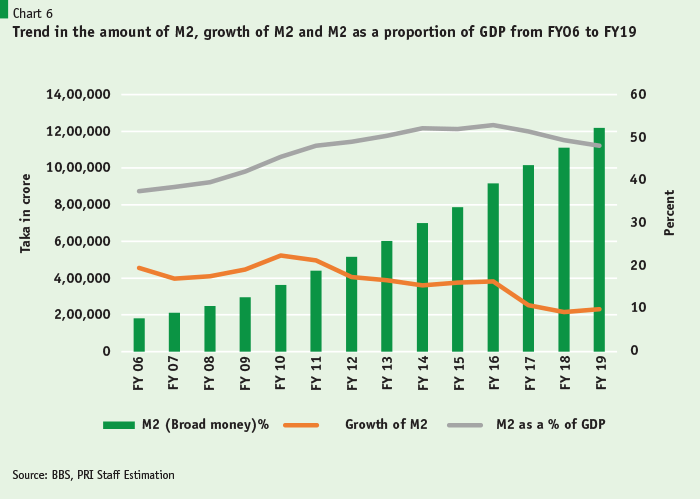

Monetary outcome however has been tight. Broad money growth in FY 2019 ended at 9.9 percent (Chart 6) below the target of 12 percent growth and considerably below the growth of nominal GDP at 12.7 percent. Thus, Bangladesh is one of the exceptional countries where high rates of growth is accompanied by a decline in financial deepening. The main reason for this decline has been the decline in private sector credit growth from 16 percent per annum in FY 2018 – which was similar to trend growth of 15 percent of the past five years and which was also the target for FY 2019 — to 11 percent p.a. in FY 2019. Conversely, public sector borrowing sharply increased in FY 2019 to 19 percent almost twice the targeted growth. These monetary developments led to the significant liquidity shortages in Banking system and the stress on Bank balance sheets as non-performing loans have markedly increased. However, one result of the constrained monetary outcomes has been that inflation remained well contained.

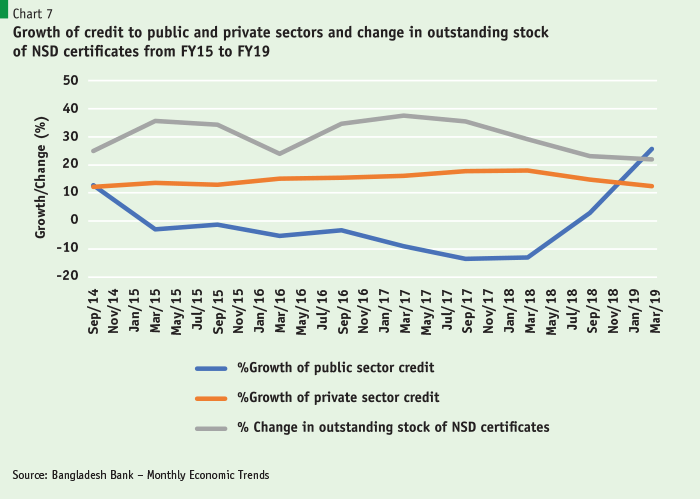

Government borrowing increased significantly in FY 2019 and the latest data shows that trend has continued into FY 2020. A new development in the monetary front has been the increasing recourse of Government borrowing from expensive special deposit and savings schemes. Riding on the high difference in interest rates between bank and NSD Certificates the government has increased its borrowing through the instrument. The outstanding stock of NSD Certificates continued to increase from Taka 2,377 billion at the end of FY18, to Taka 2,877 billion as of June 2019., i.e. a 21 percent increase (Chart 7). In FY19, the clear indication of a liquidity crisis in the banking system, portrayed by banks’ efforts to adjust their loan-deposit ratio in a time of shrinking deposits, has contributed to the slow disbursement of loans to the private sector. Thankfully, the binge in resorting to savings certificates seems to be over in FY2020 as the Government has moved to alternative sources of deficit financing.

Banking Sector Challenges

Non-performing loans and liquidity constraints in banking sector threaten stability and confidence in the financial system, which is the nerve centre of a modern economy. The sector is still struggling to recover from the recent setbacks caused by large financial frauds in several state-owned and private commercial banks. The problem has been compounded by recent changes in the tenure and family membership of bank boards. These weak regulation and governance in the banking sector and means that family ownership will have greater control in banks with the possibility of erosion of corporate governance. Banking supervision, which had improved significantly over the past two decades, is showing signs of deterioration.

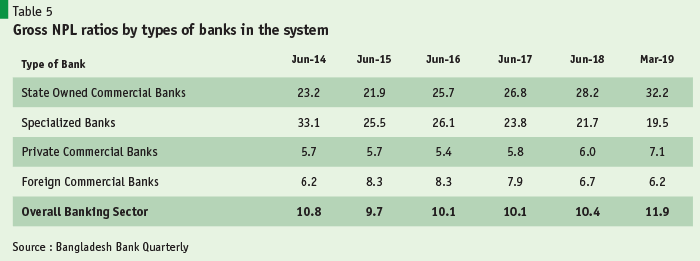

The gross non-performing loans of the overall banking sector increased from 10.4 percent at the end of FY18 in June 2018, to 11.9 percent as of the end of the 3rd Quarter of FY19, in March 2019 (Table 5). However, this number reflects the inadequate capitalization of loans. The IMF estimates, that properly defined, distressed loans may account for as much as 20% of the loan portfolio of the banking system. Overall, banking sector has continued to bleed from bad loans for years now and the worsening trend has been affecting the banks’ profit margins, scope of business expansion and the plan for job creation. As this report went to press, NPLs have jumped another notch as of September 2019 at Tk.1163 billion, 24% higher than Tk. 939 billion in December, 2018.

The condition of the State-Owned Commercial Banks (SCBs) has continued to be distressing, and unfortunately there is no relief in sight. This problem has been most serious in the case of the state-owned banks where non-performing loans accounted for nearly one-third of all loans. Partly as a result of this the advance to deposit ratios of the state-owned banks were only 60 percent compared to more than 80 percent in the case of privately-owned banks. Since the government owns these banks, their managements have no stake in efficiency or profitability of their operations. Any government is only a transitory owner with little or no immediate risk. It also has little incentive to manage these banks on a commercial footing because either the losses can be passed over to the citizens through treasury financing based on tax revenues or as continued accumulation of bad loans (i.e. NPL). Instead, there is a strong incentive to use these banks as instruments to finance politically motivated projects or to distribute political patronage.

When there is such a concentration of bad loans with big borrowers, recovery becomes nearly impossible, and loan rescheduling or restructuring becomes a fait accompli. Bangladesh Bank has responded to such pressures by markedly relaxing the definition of distressed loans. Ultimately, demands on recapitalization of the Banks out of the public exchequer may became inevitable. Regulatory forbearance, including loan rescheduling or restructuring policy favouring powerful people and lack of punishment for fraudulence in banks should set off alarm bells in the banking sector. Enforcement of laws is extremely important to control the default scenario in the country today. To play the larger role of contributing towards a stable and sound macroeconomic foundation in Bangladesh, there is no option but for the banking sector to go through the path of stricter policy, legal measures, and improvement of governance.

Enforcement of laws is extremely important to control the default scenario in the country today. To play the larger role of contributing towards a stable and sound macroeconomic foundation in Bangladesh, there is no option but for the banking sector to go through the path of stricter policy, legal measures, and improvement of governance.

Banking sector issues needs to be urgently, aggressively addressed. Urgent measures that are needed include strong corporate governance, enforcing ‘fit and proper criteria’ for banks’ directors, enhancing banking regulations, reforming state banks, tightening criteria for loan rescheduling or restructuring and enhanced legal system to accelerate loan recovery Beyond that, there is need for financial deepening through bond markets.

External Sector Developments

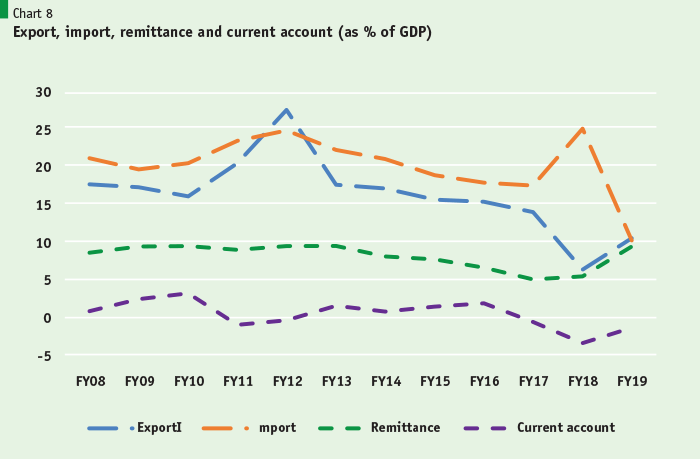

High GDP growth and its sustainability in the future will depend largely on external sector developments. A dynamically growing developing economy like Bangladesh must show robust growth in trade (import and export) as well as investment. There was a remarkable turnaround in the external sector in FY 2019 as the Balance of Payments (BoP), the Current Account balance (CAB), and the trade balance all improved significantly (Chart8). As exports grew much faster and import growth dropped significantly, the trade balance improved substantially. Remittances also grew much faster. We earned foreign exchange worth $56 billion from exports and remittances in FY2019, importing $60 billion worth of goods and services, thus leaving about $4 billion to be financed by grants and concessional loans. While Foreign Direct Investment inflows also grew markedly, they still remained significantly behind flows to South East Asian developing countries. The reversal of huge trade deficit of FY 2018 came as a relief, as such burgeoning trade deficit would have been hard to sustain for long.

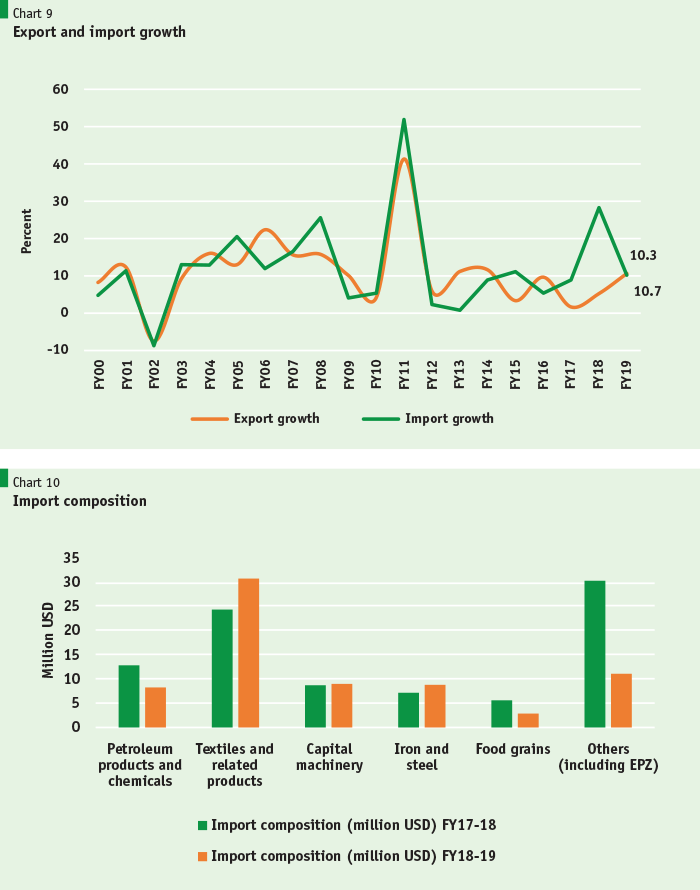

Export growth accelerated in FY 2019 after sluggish growth in the previous six years. Export growth has been tepid since FY12, with an average of around 7% growth over these years. In FY 2019, export grew by 10.6% ($40.5 billion) compared to that of last year when exports amounted to $36.6 billion. Negative strains from the Rana Plaza episode, strengthening of the US dollar, uncertainty surrounding Brexit and the Eurozone crisis were some of the main factors that contributed to a slowdown in export growth during the period FY12-17. Most importantly, it was the sharp appreciation of the real effective exchange rate (REER) that made our exports uncompetitive and dampened incentives to export. In FY 2019, the US-China trade war did provide an impetus to our exports but that could have been a temporary blip as we find exports on decline during the first four months of FY2020. Nevertheless, the image of the garments sector has improved in the world market as Bangladesh has been able to meet all the safety compliance issues made by the concerned international bodies. But the unfavourable exchange rate still poses a major hurdle to our exports going forward if the stickiness of the Taka-dollar exchange rate persists.

While the previous trend of imports outpacing exports was worrisome, the current situation doesn’t look as bleak. The current account deficit has also shown some improvements during this period, dropping to $5.7 billion compared to $8.6 billion from the same period last year, i.e. from -3.5% of GDP to -1.9% of GDP. The persistence of current account deficit indicates that, for a change, we are continuing to invest more than our savings, a gap that has been financed largely with concessional loans from multilateral agencies with a modicum of costlier suppliers’ credit and the like.

There was a marked slowdown in import growth in FY 2019. Import growth peaked at just over 10% growth in FY19 (Chart9), much lower compared to over 25% growth in FY18. In retrospect, the acceleration in import growth in FY 2018 raised concerns about financial outflows through over-invoicing of capital machinery imports. That concern is not borne out by the official import statistics which show capital machinery imports stable at about $6 billion in both FY18 and FY19 (Chart10). The implementation of various infrastructure mega-projects inevitably led to an increase in imports for capital equipment and machinery, raw materials and intermediate goods followed by fuel oil imports for power generation, all of which boosted imports – a trend that is likely to continue.

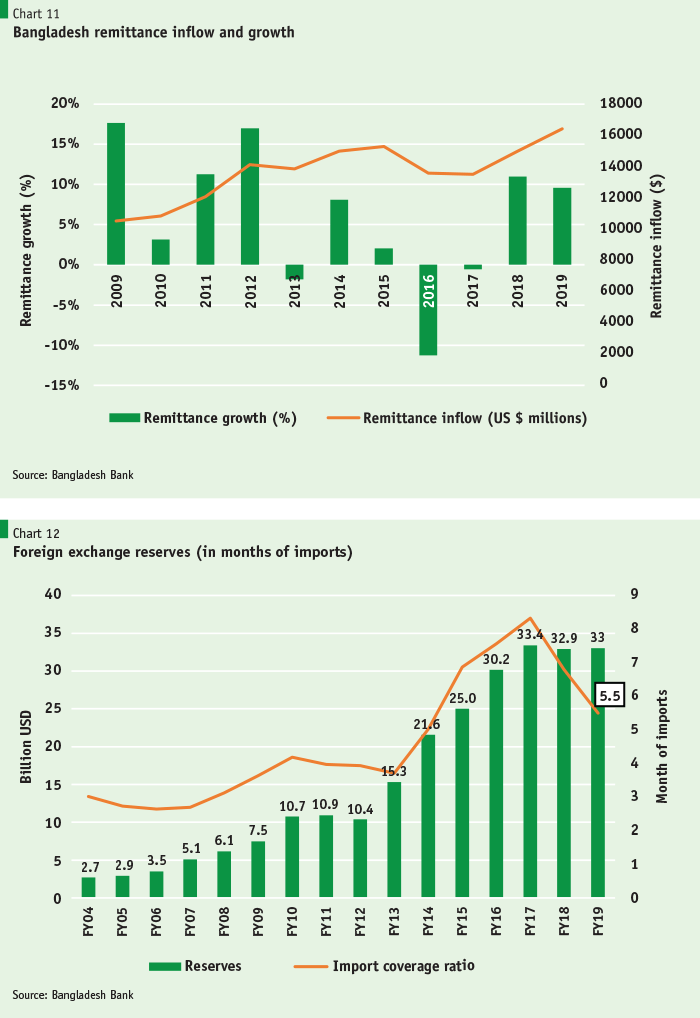

Remittance reversal. The recovery of remittance inflows in FY 2019 has helped to contain the current account deficit. Compared to last year’s remittance flow, the flow in FY19 increased by 9.5% (Chart11), a remarkable reversal compared to the performance in FY17. Analysts claim that the central bank’s role in encouraging expatriates to remit funds through official channels is one reason for the rise. However, the modest depreciation of the Taka exchange rate is likely to be one of the main reasons that pushed up remittance. Bangladeshis living abroad are remitting more money through the legal channels as their families/relatives are now getting a better rate against the dollar. The inflow of remittance has also gone up because of the strict supervision put in place by the government against hundi and high rates of dollar in specific markets. In the budget of FY20, a cash subsidy of 2% has been offered to incentivize migrant workers to remit money via banking channels. Thanks to this incentive and other measures, a remittance bounce is being observed as it is already up 22% in July-November 2019, leading to projections of about $20 billion of remittance in FY2020.

Foreign Exchange Reserves. Foreign Exchange Reserves stood at around $33 billion as of June 2019 (Chart12). The import coverage of the reserves is still a little over 5.5 months, exactly like that of last year, which is adequate for a growing economy like Bangladesh to cope with its import bills. As of end October 2019, the figure stands at $32.4 billion, after making some payments to the Asia Clearing Union (ACU). If exports and remittances don’t pick up enough to balance out the mounting import demand of a rapidly growing economy, it would be tough for Bangladesh Bank to maintain the exchange rate at current levels without additional sales of foreign exchange (having sold $2.3 billion in FY19 to prop up the Taka-dollar exchange rate).

Export competitiveness and diversification. Although China has ceded USD 30 billion of RMG in recent times, Bangladesh has not been able to capture that market share in any significant way, according to BGMEA. Product diversification of our export basket shows little movement as of now. For that to happen, Non-RMG exports will have to be given the same export regime as RMG (e.g. duty-free imported inputs in a high tariff economy). If Bangladesh graduates out of LDC status in 2024, it will be stripped off a lot of the benefits it receives currently and therefore, product diversification and geographical diversification has become a pressing need for the country. Export concentration in RMG still stands at a little over 84 percent as export diversification remains stalled. Bangladesh has yet to find emerging products with staying power.

An export diversification strategy will need to have the following elements: First, the anti-export bias of the tariff regime will need to be sharply reduced. The current protective tariff protection – very high in comparison to the export-powerhouse East Asian economies – makes domestic sales far more profitable than exports. This tariff created bias, creating a disincentive to exports, needs to be rationalized. This measure can be supplement by providing the non-RMG exports of 1392 HS-6 products (in FY18) and the 4100 exporters the same duty-free import facility as the 4000 RMG exporters of 216 RMG products. A careful application of digital technology can solve the problem of leakages from bonded system that concern policy makers. Recent PRI research has shown that competitiveness of non-RMG products is not the primary problem, trade policy is. Applying conventional competitiveness measures, of the 292 non-RMG exports (of over $1 million) in FY18, some 40% were found to be highly competitive, and another 20% moderately competitive relative to many countries exporting to the same export destinations. But these exporters are also suppliers to the domestic market where profit margins tend to be much higher. Hence the incentive to export gets largely muted.

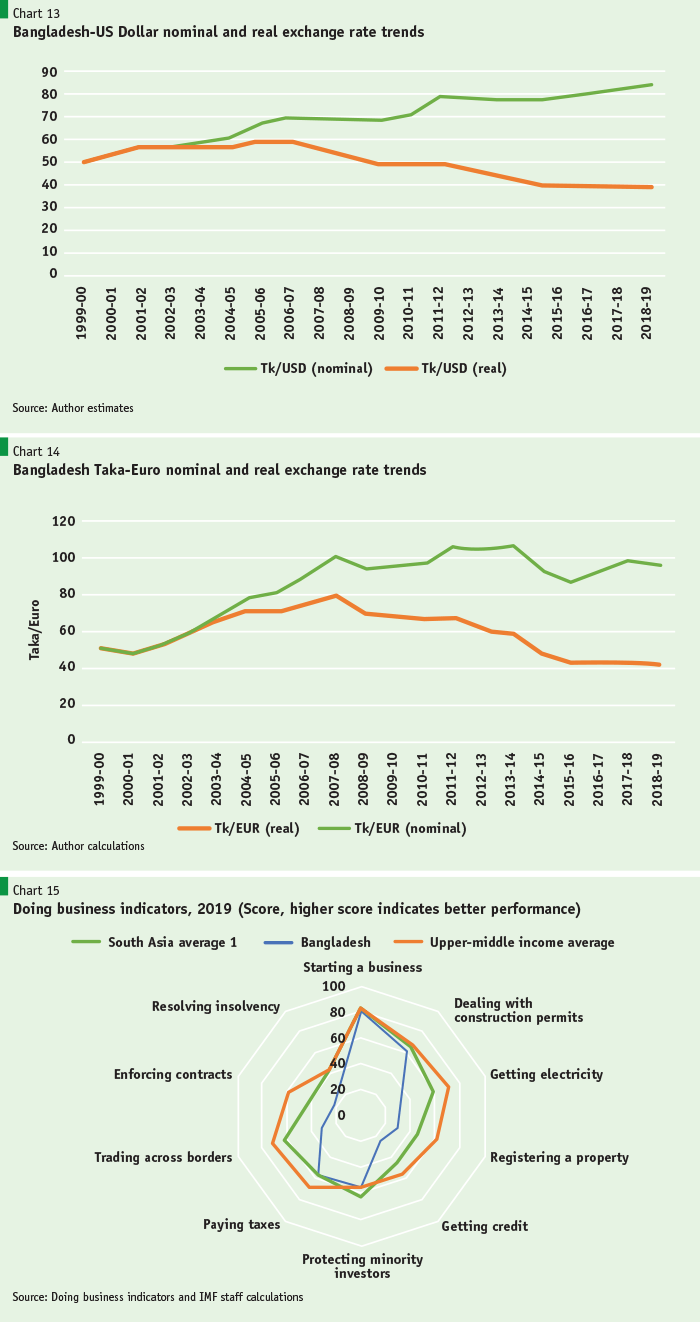

Appreciation of the real exchange rate: A second major factor underlying the weakening of export performance in recent years is the cumulative effect of the appreciation of the real exchange rate since 2006 (Chart 13-14). The Taka appreciated by 36% in real terms against the US dollar over the periods 2005-06 and 2018-19 (Chart 13). The appreciation against Euro happened a couple of years later from 2007-08. From then until 2018-19, the taka has appreciated by 48% in real terms (Chart14). This extra appreciation against the Euro reflects the fact that Taka is loosely pegged with the US dollar, which has strengthened significantly against Euro. The resultant appreciation of the dollar also transmitted into an additional source of taka appreciation against the Euro. These appreciations of the Taka in real terms against the two dominant global currencies where Bangladesh conducts much of its export trade is a real problem and has substantially hurt export prospects and stemmed the diversification of exports.

Based on the available evidence, the conclusion is straight forward. The large anti-export bias of trade protection and the additional substantial loss in export competitiveness owing to the appreciation of the real exchange rate has basically rendered the cash subsidies and other fiscal incentives for exports as ineffective instruments of export growth and diversification.

Based on the available evidence, the conclusion is straight forward. The large anti-export bias of trade protection and the additional substantial loss in export competitiveness owing to the appreciation of the real exchange rate has basically rendered the cash subsidies and other fiscal incentives for exports as ineffective instruments of export growth and diversification.

Third, partnerships with foreign investors who are well connected to foreign market and value chains should be encouraged. Without FDI, the impetus to accelerate both RMG and non-RMG export growth will be absent. FDI brings not only capital and job creation, it also provides market access, technology, and advanced management practices.

Fourth, improvements in the investment climate regime through cutting regulatory red tape, providing adequate infrastructure and logistics support will be necessary. The weaknesses in Bangladesh’s investment climate have been pointedly highlighted in both the World Economic Forum’s World Competitiveness Report and the World Bank’s Doing Business Report of 2019 (Chart15). Bangladesh’s trade infrastructure (e.g. ports, road and rail transportation, and customs administration) must be modernized to infuse export dynamism that has been missing in the past. Here, again, Government should seek opportunities to invite FDI and form public-private partnerships to develop and manage the trade infrastructure.

Over the longer run, it will be necessary for Bangladesh to position itself to take advantage of new opportunities resulting from technological change and innovation. That means more resources should be directed towards improving education quality and outcomes, vocational training, and skill development, including the reskilling of the labor force where necessary, to enable the country to take advantage of newly emerging opportunities. Bangladesh is behind our comparators in skill development, spending only 2.3 percent of GDP on education compared to the international average of 3.5 percent. Therefore, to face the challenges of the future, Bangladesh not only needs to focus on today’s jobs but also on developing skills for tomorrow’s jobs. A good model to follow here is Vietnam. Despite the slowly recovering global economy after the 2008 financial crisis, one of Bangladesh’s chief competitors, Vietnam, has shown quick progress in export competitiveness over the past few years. Apart from high growth of exports, they have managed to have a well-diversified export basket, unlike Bangladesh.

Challenges in Fiscal Management

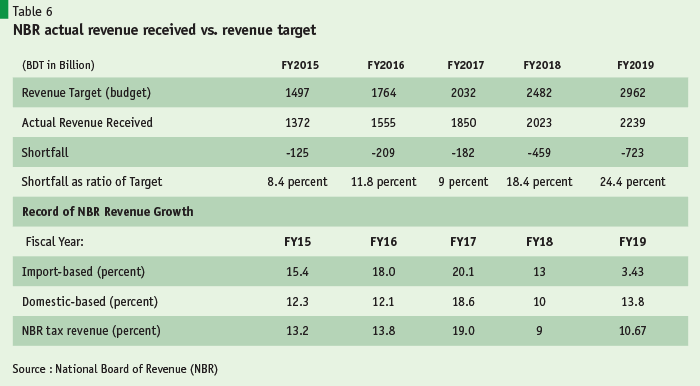

Historically, Bangladesh has an impressive track record in aggregate fiscal management. Macroeconomic balance has been anchored on a fiscal deficit of no more than 5% of GDP for the past 25 years or so. For all the shortcomings in revenue mobilization, expenditure management has been such that the actual fiscal deficit has remained well under a sustainable level of 5% of GDP (Chart16). Deficits and public sector borrowing requirements have been modest and as a result public debt is only about 34% of GDP. Debt sustainability analysis shows public debt to be sustainable. Public expenditures have been generally well allocated though questions of quality have continued to bite. In recent years, a strong push has been made to increase much needed public investment in infrastructure stemming from the simultaneous rollout of 10 mega infrastructure projects like the Padma Bridge, Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant, Dhaka Metro Rail, Karnafuli Tunnel, etc.

Still, in the medium-term, fiscal policy poses an enormous challenge for Bangladesh. The primary problem stems from the lack of fiscal space caused by extremely low tax revenue collection of under 10 percent of GDP – one of the lowest in the world. Second, expenditure allocations have also been adversely affected by rising interest payments in the last two years on account of costly public borrowing through high interest savings certificates. Expenditures on subsidies and pensions have also crowded out much needed public expenditures in social sectors and vital operations and maintenance needs Currently, interest payments are the largest single expenditure item among current expenditures, exceeding expenditures on education, health, and the highly inadequate Tk 90 billion spent on maintenance, repairs and rehabilitation.

Unfortunately, these deteriorating fiscal trends have continued in the budget for the current fiscal year FY 2020. Most reviewers agree that the FY 2019-20 budget seems extraordinarily ambitious. The budget projected an increase in revenue growth of 45 percent far higher than trend growth rates and even though the revenue outcomes in FY 2019 were one of the poorest in Bangladesh’s history. The revenue-GDP ratio has stagnated (around 10%) over the last 10 years without any major improvement; moreover, the gap between the performance and budgetary targets have increased over time (see Table 6). Important to note, the target to reach upper middle-income status and eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031 also necessitates the target of doubling of the tax/GDP ratio over the next 12 years.

In addition to having low rates of revenue collection, another significant problem is that the dependence on trade taxes that account for nearly ¼ of all tax revenue collection. Such dependence means that consumers bear the burden of high prices on one hand, and on the other hand, these trade taxes create an anti-export bias in Bangladesh’s trade regime, lowering Bangladesh’s competitiveness and economic diversification prospects. Thus, not only do revenues have to be increased, revenues from trade neutral taxes such as the value-added taxes have to increase even more to replace the trade dependent taxes.

In this year’s budget the government finally implemented the Value Added Tax (VAT) and Supplementary Duty Act 2012. However, the new law has compromised the original design with potentially serious adverse implications. For instance, four VAT rates have been introduced into the system where good practice suggests that there should be one rate and, if at all needed, a maximum of two rates. Further, several exemptions and a few even specific rates have been introduced. All these will increase administrative complexity, the costs of compliance to firms, and the incentives to evade taxes and opportunities for corruption. The firm size threshold for VAT compliance has also been raised. Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in a jump in the number of firms claiming to fall below the higher threshold. The new Act had aimed to improve the ease of doing business in Bangladesh through fully automated taxpayer friendly system of tax administration, registration and payment systems. The automated system is not ready as yet and only VAT registration process has been automated and the online process is only limited to submission of online registration form. In these circumstances, it is likely that revenue collections will suffer this fiscal year. Government will need to urgently address VAT collection issue.

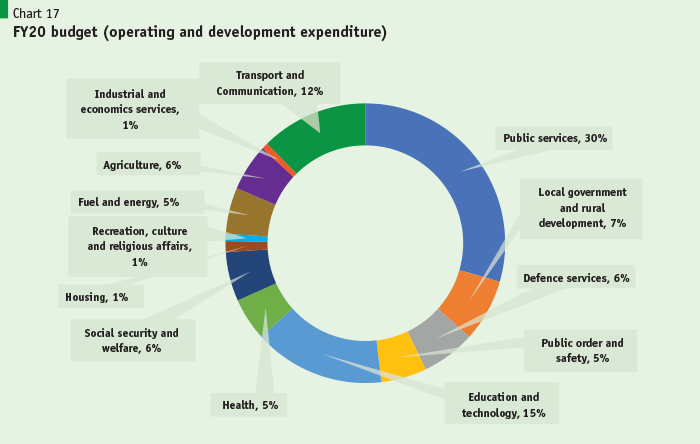

On the expenditure side, two issues need to be confronted. First, the sharp increase in consumption at the expense of vital expenditures in underfunded social sectors or in maintenance and rehabilitation of infrastructure. Fixed obligations like civil service salaries, defense spending, pensions, subsidies and interest payments are increasingly eating up the low level of available revenue resources, leaving little space for development spending out of the Annual Development Program (ADP) much needed to support GDP growth and human development (Chart17).

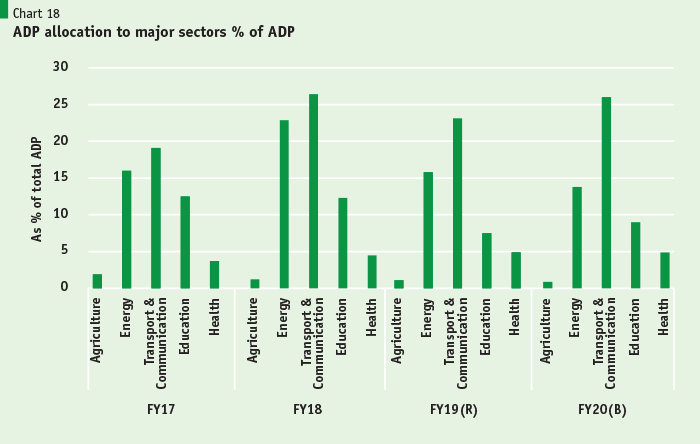

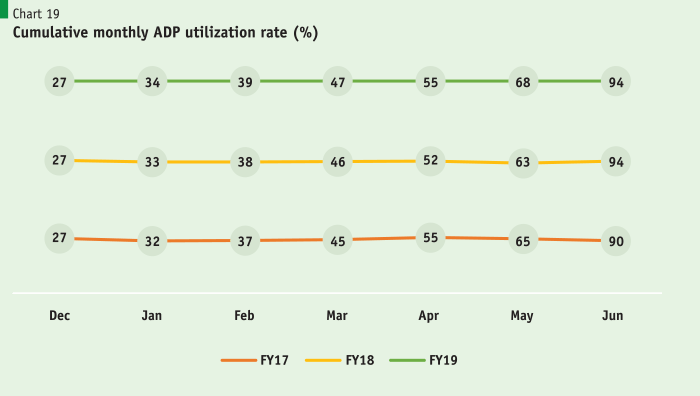

A welcome development has been the sharp increase in Annual Development Plans that provide the bulk of public investment. These expenditures have increased by 2.5 times over the past five years. The ADP utilization rates have also increased to relatively high at 94% by the end of two previous fiscal year (Chart18-19). The government’s main focus in recent years has gone to increasing its ADP allocation on transport and energy sectors, seemingly at the expense of education and health care facilities.

The main challenge in the public investment program is to ensure quality, efficiency and value for money. Project selection has to be properly vetted, competitive and transparent bidding and procurement procedures followed assiduously so that efficiency and value for money standards are attained and the returns from these investments are high. A case in point for instance is the high production costs of electricity in Bangladesh. Thus, although installed generation capacity has been increased significantly, high production costs inhibit their use. Similarly, in the case of highway construction in some cases poor quality has meant that recently built critical highways have deteriorated significantly. In implementation, a critical point is that about a quarter of the spending on these development projects take place in the last one month of the fiscal year during the monsoon rains of June when construction conditions are hazardous. As everyone who has the experience of managing projects know, the incentives to spend money to meet budget appropriation in the last month of the fiscal year is enormous and sacrificing quality become quite easy in those conditions.

Overall, expenditure allocation remains a challenge. A key issue will be to correct the balance between consumption, investment, critical operational expenditures such as maintenance and rehabilitation. Bangladesh underinvests in operations and maintenance of infrastructure. A specific instance of that is in the roads and highways maintenance. Currently, the budget provides only one-fifth of what the Roads and Highways department needs for maintenance. Overall, the revenue budget’s economic classification explicitly provides less than 100 billion BDT to maintenance and rehabilitation work. While this estimate, certainly, underestimates actual expenditure in this area, the number is frightfully low. If we, very conservatively, estimate that the Bangladesh government has 100 billion USD of public sector infrastructure in operation it implies a need of 8-10 billion USD in maintenance expenditure according to well established parameters. According to the economic classification of the budget we are providing only one-tenth of what is needed.

A Glimpse into the Future

The near-term outlook is reasonably strong, but with significant downside risks in both external and internal environments. FY2020 is the end year of the 7th FYP. Having achieved and even exceeded the targeted GDP growth rate of 8 percent, the challenge before policymakers now is to sustain and further accelerate the growth momentum in the coming decades. The 8th FYP is under preparation and the long-term goal is to end extreme poverty, achieve social and economic objectives of SDG, while reaching Upper Middle Income Country (UMIC) status by 2031, which will then pave the way for the country to move up the ladder to attain High Income status in the 2040s decade. All this would require astute planning for the next stage of economic development, making hard policy choices – often transformational and sometimes radical — to reach coveted long-term goals. Business-as-usual simply cannot be the option of choice.

How and where will the high growth come from? In our view the sense of complacency built around the notion that the growth momentum attained over the past decades will continue into the future is misplaced. Historically, no country has attained and sustained GDP growth of 8% or more without leveraging trade with the global economy. The world economy offers a vast marketplace to be penetrated with competitive products allowing economies to grow at 7,8,9, and 10 per cent per annum. Bangladesh cannot seek higher growth relying on the domestic market alone. Hence, it is time to gear up for a more open trade regime that makes exporting (and importing) a dominant economic activity in the coming decades. Only trade-led growth can yield further acceleration in our growth momentum.

Of course, this has to come while maintaining macroeconomic stability which is the fundamental basis for high growth. For all the shortcomings in revenue mobilization, Bangladesh has been credited with prudential macroeconomic management that kept the fiscal deficit within a sustainable 5% of GDP for nearly three decades, making it the anchor of macroeconomic stability. That remarkable macroeconomic configuration should be maintained for the long haul.

…Bangladesh must invest in training its people and labor force, an area where it now significantly lags behind. To harness this dividend, the country will need to invest in infrastructure and improvements in the business climate so that both domestic and foreign investment are encouraged to provide productive jobs for the growing work force.

Finally, Bangladesh’s growth prospects in the next two decades will be bolstered by its young population and the growing share of the working age population — the country’s demographic dividend. A dynamic region such as East Asia achieved high rates of growth with the help of its demographic dividend. However, growth does not follow a demographic dividend automatically. To be able to utilize it as East Asia has done, Bangladesh must invest in training its people and labor force, an area where it now significantly lags behind. To harness this dividend, the country will need to invest in infrastructure and improvements in the business climate so that both domestic and foreign investment are encouraged to provide productive jobs for the growing work force.

Though Bangladesh economy and its people have shown great promise and potential for societal rejuvenation, let us acknowledge that the road ahead is long and rather steep. To make our future brighter than the past, a business-as-usual approach is no longer an option.