The Missing Link in FY2021 Budget Robust Trade Policy for Economic Recovery

By

Nobel Laureate economist and leading growth expert, Paul Romer, once famously remarked, “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste”. A crisis builds resilience and instils fortitude and determination to make changes and seize opportunities. Back in 1990, the economy was subjected to a political-cum-economic shock. Growth faltered, and the balance of payments was in shambles. Democracy was re-established. Seizing the moment, the economy changed directions during the 1990s decade, moving from an inward looking highly interventionist regime to an outward-looking, market-oriented, economic system. To this day, we believe that those trade policy reforms were the most radical and deep-rooted – import liberalization, tariff rationalization, exchange rate flexibility, limited current account convertibility, and embracing of export-led growth. Internally, investment was liberalized, directed credit and interest rates were discarded, and state intervention in markets were minimized, with the state committed to play a facilitating role. Market orientation of the economy changed radically towards the free market. The rest is history.

These changes brought more dynamism into all segments of the economy as was never seen before. The gains from those changes in direction are now writ large on the face of the economy and society. Exports averaged double digit growth for nearly 20 years since 1992. In the last decade, the economy clocked GDP growth of 7.4%, became a lower middle-income country in 2015, and was on course to graduate out of LDC status in 2024, when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. It was a global output-cum-trade shock of enormous proportions transmitted around the world. Bangladesh, now much more integrated with the world market, could not be immune to this unprecedented crisis. But, if history is any guide, a crisis also creates opportunities. So we cannot and should not let this crisis go waste.

Covid-19 pandemic has delivered a health-cum-economic shock to the Bangladesh economy disrupting, hopefully temporarily, its onward journey towards becoming a Middle Income Country (MIC) by 2031, after graduating out of LDC status in 2024. To my mind, this disruption is unlikely to shift those two critical national milestones up ahead. FY21 Budget confirms that. In that case, we need to lay strong foundations for not only cushioning the shock from the Covid-19 pandemic but also to stimulate a robust and sustainable economic recovery. To this end, the government’s fiscal and monetary stimulus package along with FY2021 Budget should provide strong ammunition on the path to economic recovery. Initial estimates suggest the number of poor people (32 million or 20% of the population) might have risen to 50 million, as many living above the poverty line fell into poverty having lost jobs and livelihoods. Given the enormity of the health-cum-economic crisis, in all likelihood more resources might be needed until the crisis is behind us. One would hope that the FY21 Budget would be the first comprehensive policy package to address the immediate shock from the crisis and lay the foundations of a rapid economic recovery.

When it comes to the Budget there is so much to talk and write about. So at the outset let me stay focused on what could be a rather narrow but quick take on one particular aspect of the budget that is usually left unattended, by the budget itself as well as its vocalists around town: Trade Policy. It is one of the three major policy components of macroeconomic management of the economy – fiscal policy, monetary policy, and trade policy, yet the one least talked about. Overall, Bangladeshis should be thankful to our policymakers who, for all their shortcomings that we are often quick to point out, have been prudent enough to ensure stability of the macro economy for over three decades, creating the right conditions and environment on which to build ambitious plans for the future. And all this happened in the face of heavy odds arising from natural and man-made calamities striking the economy and society, time and again. Covid-19 crisis is only one – albeit perhaps the severest – among many such episodes in Bangladesh’s journey traversing half a century.

For the time being, the monetary and fiscal package puts Tk. 1.1 trillion (3.5% of GDP) on the table directed at four response areas: (a) expansion of social safety net programs, (b) increased public expenditure, (c) providing fiscal stimulus to business, and (d) monetary easing to expand credit and promote investment. All of these are just what the doctor ordered. A closer look however reveals that much of the package goes to expand ‘lending’ rather than ‘spending’, and Bangladesh Bank will have to prod the commercial banks to lend more and fast. Hence the fiscal cost of the package is much lower, estimated at about $4.3 billion (about 1% of GDP). The FY21 Budget of Tk. 5.7 trillion (18% of FY2021 GDP) of planned public expenditure also adds additional resources within the allocation of various ministries to combat the crisis and fuel recovery. We should not be surprised if more fiscal resources become necessary to cope with the rapidly evolving crisis.

First and foremost, the FY21 Budget is a rendering of the Government’s fiscal stance or fiscal policy. A prudent fiscal deficit of 6% of GDP is programmed for the year with expected revenue mobilization of 12% and expenditures of 18% of FY21 GDP. The Covid-19 impact, which is a combination of supply and demand shock to the economy, has left FY20 revenues in shambles – actual revenue mobilization until March 2020 was a meagre 6% of GDP. Unless FY21 GDP itself underperforms significantly, 12% revenue target will be a stretch by any imagination.

Nevertheless, fiscal policy for FY21 continues on a traditional expansionary path, though some economists would argue for the need of a larger budget deficit of 7%+ in these challenging times. The low public debt-GDP ratio of 35% leaves wiggle room for some temporary surge in public spending, if that is to save lives and livelihoods. Leading economists of the world have argued that this is not the time to worry about “debt and deficits”. Governments around the world have thrown the kitchen sink at this pandemic-induced economic crisis. That should give some guidance to our policymakers to not leave any stone unturned and go the extra mile to save lives and livelihoods.

Though our expectation was for a larger Budget deficit this time, erring on prudence dictated a 6% (of GDP) deficit target which has been set with external financing of 2.5% and domestic financing of 3.5%. As for external deficit financing of 2.5% of GDP, provided that we do our homework diligently and undertake a few good policies, the prospects of adequate low-cost multilateral financing are quite good this year of Covid-19 global response. Already, commitments of over $2.5 billion from the World Bank, ADB, and IMF appear to be on the cards. After all, a sluggish global economy is good for no one and multilateral agencies have a role to keep things moving.

Monetary policy comes into play in financing the fiscal deficit, particularly the domestic financing part, which the Budget sets at 3.5% of GDP (Tk.1.1 trillion). Inflation targeting, interest rates, credit growth, and money supply are all affected by the stance on domestic financing of the fiscal deficit. This is where fiscal and monetary interdependence comes into play. So much of monetary management stems from the fiscal deficit that it seems so far-fetched to talk of central bank autonomy in the Bangladesh context. Fiscal-monetary policy coordination is the sine qua non of our growth strategy as much as it is now an essential component of Covid-19 crisis management and economic recovery not just in Bangladesh, but around the world. Covid-19 pandemic has invoked a symbiotic relationship between monetary easing and fiscal stimulus policies like never before.

So where does trade policy belong in all of this. Global trade has been a major casualty of the global supply and demand shock of Covid-19 pandemic. While IMF projects global output to shrink by 4.9% in 2020, but a pick up of 5.4% growth in 2021, the multilateral institution projects a steeper decline for global trade – at 11.9% decline, but faster pick up in 2021 at 8%. However, IMF adds that there is a lot of uncertainty about the future making these projections rather tentative. That puts Bangladesh export prospects in 2020-21 in serious jeopardy. But we remain optimistic counting on a V-shaped recovery in the world economy as well as our own. So the FY21 Budget stipulates exports to recover at 15% growth, a jump from -10% negative shock in FY20. This matches the highly optimistic GDP growth assumption of 8.2% for FY21, though ADB has lately revised its own growth optimism downward to 7.5%. The first impression one gets from the Budget is that monetary and fiscal policies together might do a good job of coping with the immediate Covid-19 impact but lacks the jet fuel needed to boost the economy from a Covid-19 induced coma to a rapid recovery of 8%+ growth. This is particularly true in the absence of a trade policy stance of any magnitude. Here, one gets the impression from the Budget that if there is something called trade policy, it hardly matters.

But it is trade policy that links the global marketplace with our economy. Trade policy is the mechanism through which developing economies can leverage the vast global market for exports, job creation, and GDP growth. Leading growth experts of the world have concluded, in no uncertain terms, that the history of rapid growth performance of 7-8 percent reveals that it is the strategy of leveraging global markets through export-oriented manufacturing that yields such high growth. History of Bangladesh economy tells us that our economy has been successfully doing just that. Domestic markets, because of their limited size, simply lack the scale economies needed for the kind of industrial expansion that creates millions of jobs and stimulates growth. Understandably, Covid-19 pandemic has put a damper to this line of economic reasoning but it cannot be the end of it. For all its shortcomings, globalization is irreversible, and Bangladesh is among the significant beneficiaries of the globalized world. We should continue to harness the positive gains from this global regime through greater trade integration even in the post Covid-19 world. Adopting the open stance of trade policy is and will remain the right approach. While the Bangladesh economy has demonstrated its ability to grow at 7-8% in recent years, historical and cross-country research tells us that such high rates can only be maintained by leveraging the vast global economy through greater trade integration. It would be nice if our Budgets acknowledge this theoretical principle that Nobel laureate economists and leading growth experts endorse.

While the Bangladesh economy has demonstrated its ability to grow at 7-8% in recent years, historical and cross-country research tells us that such high rates can only be maintained by leveraging the vast global economy through greater trade integration.

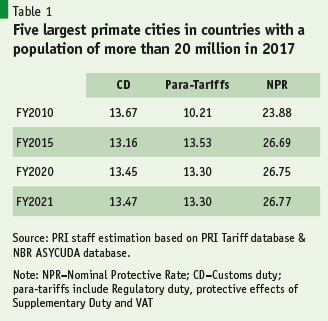

This is where one finds that the FY21 Budget sets the trade goals right but the trade policy means appear lacking. Note also that this Budget launches the first year of the 8th Five Year Plan (2021-25) which is expected to build an ambitious program of export-oriented industrialization on the heels of good achievements made during the period of the 6th and 7th FYP. Recognizing the vulnerability associated with export concentration in RMG, the Budget rightly emphasizes export diversification as a priority goal, highlighting a long list of non-RMG products that will be receiving government support for their expansion. But apart from an occasional reference to reducing an input tariff or raising an output tariff, ostensibly to protect an industry, what is conspicuously missing is a concerted trade policy program of setting the balance of incentives right. All of the non-RMG products cited (e.g. footwear, plastics, electronics, agro-processing, furniture, etc.) are import substitutes which are highly protected in the domestic market with the highest tariffs and para-tariffs, making their domestic sales far more lucrative than exports – classic case of anti-export bias. The biggest challenge in Bangladesh’s trade policy is to rationalize protective tariffs strongly enough to at least make relative incentives between exports and domestic sales equally profitable. One would have hoped that it would be the objective of “tariff rationalization” mentioned in the FY21 Budget but it turns out not to be. Preliminary assessment of tariff adjustments indicate not much has changed in the tariff structure and trends (see Table 1).

The biggest challenge in Bangladesh’s trade policy is to rationalize protective tariffs strongly enough to at least make relative incentives between exports and domestic sales equally profitable. One would have hoped that it would be the objective of “tariff rationalization” mentioned in the FY21 Budget but it turns out not to be.

As one can see, para-tariffs, which make up 50% of our nominal tariffs (para-tariffs are practically ignored in WTO reviews), make up the additional protective components of our tariff structure and they are left unchanged, just as the average CD. A key part of tariff rationalization in the future will have to deal with the scaling down of those para-tariffs in the future, hopefully sooner rather than later. Covid-19 pandemic could be the crisis that could break the camel’s back. If we do want an economic recovery, backed by export recovery, fueled as much by export diversification, then we have to do something about this outmoded tariff structure that is so unique among developing economies. We have shown repeatedly how this kind of tariff structure stifles exports pre-pandemic and will be even more stifling in our post-pandemic attempts at export recovery. Thankfully, RMG exports remain immune to this inhibiting protective structure because of bonded warehouse system that allows duty-free imported inputs at competitive world prices. For RMG, it is time to look East, to China (which has offered DFQF to 97% of imports from Bangladesh) and Japan (which already offers limited DFQF). The two economies add up to a market of $19 trillion, higher than EU market of $18 trillion and slightly below US market of $21 trillion. RMG geographical diversification in the post-pandemic era could be a saving grace or even a game changer.

Let me end with a few final remarks about our exchange rate stance – a pivotal component of trade policy. The system of fixed exchange rates has long been abandoned around the world shifting in favor of flexible exchange rates. Economies that have achieved export success have all shown one common trait – they strictly avoided overvaluation of their currencies and often chose to keep their exchange rates under-valued (i.e. depreciated). Bangladesh floated its exchange rate in 2004. But, like most countries, it stuck to a regime of “managed float”, where the Bangladesh Bank strictly monitors the movement of the exchange rate and intervenes, apparently to keep the nominal exchange rate from depreciating too much too fast (i.e. more Taka per US dollar). PRI research has shown, in many write ups, how that real effective exchange rate (REER) has significantly appreciated over the past five plus years undermining export competitiveness. Exporters suffered as they were not getting a decent taka value of their export sales. A 1% cash incentive to RMG exporters and 2% incentive for remitters is no match to, say, a 5-10% depreciation of the exchange rate that has remained steady at Tk.84.5-85.0 per US$ since January 2019. It is important to note that 5-10% depreciation of the exchange rate is equivalent to a 5-10% cash subsidy to all exports and remittances, across the board, and the cash subsidy does not have to come out of the public exchequer. PRI research has also shown the way to counterbalance any inflationary effects of such a depreciation, by downward adjustment of tariffs without affecting customs revenues. As for the final argument that such depreciation will raise the cost of external debt financing, may I add that our external debt servicing rate is a mere 4% of our foreign exchange earnings, which will not change, except that Taka fiscal cost may rise 5-10% — a minor irritant for an economy whose low level of indebtedness has been recognized recently by The Economist (Bangladesh was ranked 9th among the least indebted countries of the world).

It is important to note that 5-10% depreciation of the exchange rate is equivalent to a 5-10% cash subsidy to all exports and remittances, across the board, and the cash subsidy does not have to come out of the public exchequer. PRI research has also shown the way to counterbalance any inflationary effects of such a depreciation, by downward adjustment of tariffs without affecting customs revenues.

To conclude, the FY21 Budget of Tk.5.7 trillion combined with the Government’s monetary-fiscal stimulus package of Tk.1.1 trillion, as well as all the administrative mobilization for addressing the Covid-19 pandemic emergency, are all timely and appropriate, and will go a long way in coping with this national emergency. It is the economic recovery part that might need more than what the budget has put on offer. As the global economy wakes up from the slumber of Covid19, Bangladesh will need more robust trade policy and vigorous export strategy to make any headway in FY2021 and beyond. Covid-19 induced crisis presents the grounds for drastic measures for radical adjustments in trade policy – as done in the early 1990s in the wake of a political-economic crisis. Business-as-usual pre-pandemic trade policy is no longer an option. Otherwise, the goal of 15% export pick up, export diversification, and 8.2% GDP growth in FY21 could all end up in smoke. I repeat: a crisis is a terrible thing to waste.