Critical Need for Bangladesh’s Development-Export Seeking FDI

By

As globalization took hold in the post-WWII era, developing economies have increasingly sought foreign direct investment (FDI) as an engine of economic growth and development. In pursuit of this goal, many governments around the globe have tried to attract FDI by offering generous financial and tax incentives. Bangladesh followed suit.

Attracting copious amounts of FDI is not just aspirational. It is a critical need for Bangladesh’s development journey. Bangladesh faces an immediate challenge – of transforming from a Lower Middle-Income Country (LMIC) to an Upper Middle-Income Country (UMIC) in a decade, besides shedding the ubiquitous title of a least developed country (LDC). For this to materialize, it will require FDI inflows into Bangladesh in volumes not seen before. Are we ready?

Our FDI inflows averaged USD 2.7 billion during FY2016-19, with a total of stock of about USD 18 billion. This may be seen in the context of USD 1.54 trillion global FDI inflows in 2019, with the USA topping the list of recipients at USD 246 billion. According to UNCTAD, China, which attracted the second largest inflows of USD 141 billion in 2019, has accumulated FDI stock of USD 1.77 trillion – by far, the largest volume for a developing country. If the largest and second largest economies of the world are so vigorously courting FDI, it must be a prime mover in the global economy as well as in their respective national economies.

For developing economies seeking rapid growth, international trade and its consequential corollary, foreign investment flows, have become the quintessential handmaidens of transformation and growth. Quite apart from the capital that comes with foreign direct investment (FDI) to bridge the national investment-savings gap in a capital scarce economy, the more important aspects of FDI to be recognized and subsumed in policymaking include its role as a vehicle of technology transfer, facilitator of capacity building in human capital (e.g. management and worker skills) and job creation, stimulating domestic investment, bringing access to global markets, and contributing to strengthening business institutions.

However, to extract all these consequential gains the key will be to ensure an atmosphere of FDI where the spillover effects to the domestic economy is maximum. For that to happen, the challenge is to develop an effective channel for drawing and absorbing the maximum positive spillovers from FDI supplying multinationals into the domestic economy. Two spillover mechanisms could work. First, domestic firms can benefit from the presence of multinationals in the same industry, leading to intra-industry or horizontal spillovers through the movement of workers within industries, demonstration effects, competition effects, and so on. Second, there may be spillovers from multinationals operating in other industries, leading to vertical spillovers, through backward linkages with upstream industries (e.g. RMG linked to primary textiles), or forward linkages with downstream industries (e.g. parts and components of mobile phones or computers linked to manufacturing plants of mobile phones or computers).

… to extract all these consequential gains the key will be to ensure an atmosphere of FDI where the spillover effects to the domestic economy is maximum. For that to happen, the challenge is to develop an effective channel for drawing and absorbing the maximum positive spillovers from FDI supplying multinationals into the domestic economy. Two spillover mechanisms could work.

Studies suggest that drawing FDI only into export processing zones (EPZ), which basically operate as free trade enclaves in Bangladesh, practically delinks FDI from the rest of the economy. This severely constrains the spillover transmission effects. Such limitation could potentially be overcome through the setting up of special economic zones (SEZ) or designated industrial parks (with country sourcing) that are not enclaves like EPZ but have closer links to the domestic economy, with policies designed to maximize spillover effects, like providing generous incentives for joint venture and setting minimum intake of local labor requirement.

Fortunately, data reveal that bulk of FDI inflows into Bangladesh are invested outside EPZs, implying maximum possibilities of spillover transmissions. Of the USD 354 million of FDI in FY01, 84% were invested outside EPZ; that share rose to 94% in FY19, thus presenting enormous scope for all the positive transmission effects of FDI into the domestic economy. Of course, at the end of the day, how much a country can absorb the FDI spillovers will be determined by the quality of initial stock of human capital and infrastructure, laws, institutions and capacities for public service delivery, and the prevalence of sound macroeconomic policies together with significant trade openness.

Make no mistake, FDI is a business undertaking by the foreign investor. The quantum and destination of FDI inflows are singularly determined by the evaluation of returns and risks and the consequent attractiveness of investing in foreign lands. Higher the returns versus risks, greater the inflows of FDI. Attracting FDI then becomes a competitive enterprise in itself. Creating the ideal investment climate through the formulation of the friendliest rules and generous incentives make economies more attractive destination than others. Not to be ignored, in the post-Cold War world, there is always an overlay of geopolitics that could be either a deterrent or facilitating factor.

Since the 1990s, Bangladesh laid out perhaps the most liberal FDI regime in South and East Asia for attracting foreign investment. There is a comprehensive list of incentives on offer including 100% foreign ownerships, full repatriation of invested capital and dividends, generous tax holidays, duty-free import of capital machineries and intermediate goods, no ownership limits in Joint Ventures, Partnerships, PPPs, Non-Equity Modes (Technology Transfer, Licensing, Franchising, Contracting, etc.), access to local financial institutions for working capital, legal protection to foreign investments in Bangladesh against nationalization and expropriation, equal treatment of both local and foreign investments. Although these policy commitments make up an extremely liberal FDI regime on paper, in practice they are not enough to result in a favorable investment climate that is welcoming of FDI. In comparison to other economies seeking FDI, poor infrastructure, bureaucratic logjams, pervasive corruption, weak legal system for enforcement of contracts, and perception of political instability, all add up to convey an investment climate that is all too prohibitive to bring massive inflows of FDI, away from other competing destinations in the region. In my view, that perception could be changing if we play our cards right in setting up the planned special economic zones (SEZs) in good time and with all the committed infrastructure facilities and incentives duly fulfilled. This is our chance to bid FDI away from other competing destinations that are eagerly courting scarce private capital, technology, and dynamic enterprise.

In comparison to other economies seeking FDI, poor infrastructure, bureaucratic logjams, pervasive corruption, weak legal system for enforcement of contracts, and perception of political instability, all add up to convey an investment climate that is all too prohibitive to bring massive inflows of FDI…

Typology of FDI

In casting their net wider in the global economy, studies show that investors seek to fulfill a variety of objectives in putting their capital in a foreign country. Some of these investment objectives could be identified as export seeking, tariff jumping, resource or asset seeking with energy concessions, and enabling global value chain (GVC) integration.

Export seeking FDI

It turns out that the largest investors across borders are multinational enterprise (MNEs), whose origins are no longer limited to North America and Europe. A rising number of MNEs are now located in East Asia and the Pacific. When MNEs are searching for investment destinations a major goal is to locate in an economy where they can produce at internationally competitive costs and reach global markets. According to UNCTAD, MNEs account for two-third of world exports which in turn generate the impetus for trade expansion. FDI flows and expanded trade go hand in hand. This is particularly true for FDI-driven manufacturing exports. Studies have found robust evidence for positive horizontal spillovers from export-oriented multinationals. Once grounded in a host country, export-oriented FDI brings adequate capital resources to leverage the vast global marketplace with unlimited demand delivering job creation and growth in the host economy. However, domestic-market-oriented MNEs also generate positive spillovers through backward linkages for both domestic exporters and non-exporters. Backward linkages from FDI-driven exports or domestic sales serve as a conduit for positive productivity spillovers from foreign direct investment.

Bangladesh presents an ideal destination for such export-seeking FDI that ensures not only low-cost production but, given its LDC status, also opens markets with duty-free entry in Europe and elsewhere. Of course, the economy’s FDI-driven export potential is undermined by the weakness in overall investment climate and the degree of restrictiveness of its trade regime.

Tariff-jumping FDI

A large market protected by high tariffs and other non-tariff barriers could pose a major incentive for foreign direct investment (FDI) with or without joint ventures. If production costs are low and complementary infrastructure and institutions are available, high protective tariffs create the incentive for MNEs to jump tariffs and set up production in the host country (e.g. automobile production in India). Output from such production could then be directed to sales in the local market or exports, or both. This sort of FDI could also be deemed as “market-seeking”. Provided the host country market is large enough to offer scale economies, and tariffs on intermediate inputs are sufficiently below output tariffs, tariff-jumping would make sense with the intention of targeting the domestic market. Note that higher the protective tariffs, higher the incentive for tariff-jumping. Major automobile producers of the world and other MNEs producing durable and non-durable consumer goods engage in such tariff-jumping FDI. Among developing countries, large economies like China and India are attractive markets for this kind of FDI though, as incomes rise resulting in substantial growth of MAC population (affluent middle class), many more developing economies are likely to become attractive destinations in the future. Which includes Bangladesh. The fact that input tariffs in Bangladesh are significantly lower than output tariffs, this could be a favorable condition for firms looking for greater trade openness to facilitate low cost importation of intermediate inputs. But, is the domestic market large enough and trade openness sufficient to offer seamless import-export and scale economies for higher returns?

Resource exploitation or asset-seeking FDI

The presence or potential discovery of oil, gas, other minerals, or agricultural products (e.g. cocoa, coffee) could encourage FDI inflows with the goal of exploiting these resources for exports or meeting the demand for industrial raw materials in the source country or elsewhere. Asset-seeking FDI usually refers to those instances where the investor is looking for acquiring strategic assets like technology, management and innovation skills mostly found in developed countries or emerging economies well advanced in ICT development. However, another form of asset-seeking FDI could involve partial or full ownership of energy related enterprises like gas and power generation projects. Because of mostly state-guaranteed contracts involved in such resource or asset-seeking FDI, analysts have suggested that the inflows of this type of FDI is not always constrained by an otherwise poor investment climate. The presence of proven or potential supply of exhaustible natural resources could be enough to attract FDI albeit a favorable investment climate could be a boon.

GVC-seeking FDI

The fragmentation of production processes across different countries has given rise to global value chains (GVCs) creating opportunities for intra-industry trade globally as well as between contiguous economies within a region. To exploit GVCs, entrepreneurs may exploit two specific options: (1) produce intermediate goods (parts and components of manufactured products); or (2) emerge as an ‘assembling’ hub. With regards to the first, a successful strategy would be to establish strategic partnerships with established multinationals who will assemble the final product in another location.

In the past 25-30 years, trade in intermediate goods has become the fastest growing component of international trade. Multinationals are the repository of technical ‘know-how’ needed for the production of an intermediate good in the GVC. In this context, a prudent strategy for local entrepreneurs is to opt for a collaborative production structure that builds long-run commitments between local and foreign actors, so that the technical ‘know-how’ needed by the local actors is obtained by inviting FDI.

On the other hand, if local entrepreneurs are willing to devote resources to assembling activities, then they should choose a product where there is a high local demand in addition to high export demand. The security of sales in the domestic market will attract FDI from the foreign firm, and a collaborative production structure will diffuse the initial technical know-how needed. This option has worked well for China which succeeded in exploiting GVCs to emerge as an ‘assembling’ hub. East Asian countries have seized early opportunities from this development by linking up with China – the world’s assembling powerhouse. Notably, Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Cambodia, have jumped on the bandwagon, creating an East Asian “hub-and-spoke” GVC and supply chain configuration for “just in time” delivery of intermediate goods. Covid-19 crisis dealt a serious blow to this regional arrangement which involved exclusive dependence on few selected suppliers, leading to new thinking in the direction of “just in case” configuration that now calls for wider distribution of supply chains across the globe. Recall that when Wuhan started as the epicenter of the crisis and factories were shut down, our RMG and textiles, which relied exclusively on Chinese supply of dyes and chemicals that came from Wuhan, experienced a supply shock even before Covid-19 struck Bangladesh. That is a clear signal to diversify supply chains in future.

So where does Bangladesh stand in terms of the state of FDI inflows and its links to the economy’s dynamism and progress. Sadly, with USD 2.8 billion in FY2019 the quantum of FDI inflows (including reinvestment) has hovered around 1% of GDP for quite some time without showing signs of any upward trajectory. Relatively speaking, this gives a poor picture of FDI role in the economy when comparators like Vietnam and Thailand are raking in US$ 15-20 billion a year.

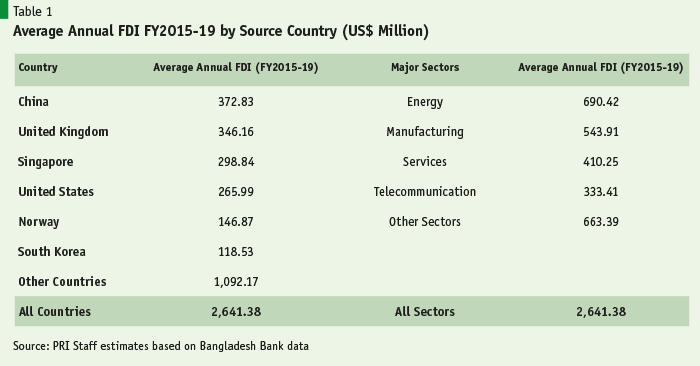

Since FDI inflows from source countries fluctuate widely every year, taking averages for a 5-year period gives a better picture of how source countries stand with regard to their FDI presence (Table 1) in Bangladesh. China is now the clear leader averaging USD 372.8 million during FY2015-19 with USD 626 million invested in FY2019 alone. Next, UK, USA, Singapore, South Korea and Norway are the other countries with significant presence. With massive public and private investment being undertaken to create adequate power generation capacity in the country, it is no surprise that Energy (Power) attracted the most FDI, followed by manufacturing (textiles and food), and telecommunications. Are we getting the most out of FDI?

As mentioned earlier, the fact that 94% of FDI is outside EPZ, it is possible to infer that the predominant type of FDI has been geared to the domestic market – the market seeking FDI (power, telecommunications, food processing). In principle, transmission of spillover effects should be maximum in such a case. Export-seeking FDI has been limited and largely confined to the EPZ. This corroborates the report that Bangladesh’s leading manufacturing sector, RMG, is still not welcoming of competition from foreign investors and de facto restrictions by the dominant associations discourage FDI presence in this sector which in turn constrains FDI in other forward and backward linkage activities. High protective tariffs notwithstanding, there is not much incentive for tariff-jumping FDI in view of the fact that trade policy and customs administration is still perceived as being restrictive for seamless movement of import-export goods and the domestic market is still not large enough to generate scale economies. It could be for the same reason that there is not much traction in GVC-oriented FDI for which a high degree of trade openness is an essential prerequisite. All in all, the entire package of trade and investment policy, trade infrastructure and relevant institutions, fall short in attracting FDI. Furthermore, the fact that much of our FDI is geared to the domestic market, its further proliferation is also limited by the size of the domestic market, unlike the vast global export market, which is the destination of export-seeking FDI.

This is in sharp contrast to the FDI scenario in our neighborhood – if East Asia can be considered such. China and Vietnam have been in the forefront of FDI recipients like no other developing country. While China is out of our league, a closer look at the Vietnam trade and foreign investment experience would be worthwhile because this is an economy slightly smaller in comparison to Bangladesh, having a GDP of USD 261 billion in 2019. Notwithstanding the fact that it is a socialist country, Vietnam launched its program of “Doi Moi” in 1986 embracing a “Socialist-Oriented Market Economy” (SOME). Following radical market-oriented reforms the country has achieved extremely high level of trade integration with total trade reaching USD 500 billion in 2019, almost twice its GDP of USD 261 billion, and exports of USD 263 billion ! What is notable is that FDI played a significant role in this exceptional export performance with inflows of USD 16 billion in 2019 and a stock of USD 161 billion. Vietnam, a long-time ASEAN member, is an extremely attractive destination for export seeking FDI as its exports have almost duty-free access to large markets around the world due to its FTA arrangements with several regional blocs like Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), EU, Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), in addition to ASEAN Plus FTAs with Australia, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Reciprocity is a fundamental requirement of FTA which takes a long time to materialize, from start to finish. To reach FTA deals with these blocs of countries, Vietnam had to open up its own economy to potential import competition from these economies.

While China’s manufacturing industries experience rising costs of production and grimmer prospects due to US-China trade tensions, Vietnam is trying to position itself as Asia’s new manufacturing center, particularly in the electrical and electronics sector. In fact, the country exported high-tech goods worth USD 43 billion in 2016 – higher than those of its neighbors Thailand (USD 34 billion), Philippines (USD 32 billion) and Indonesia (USD 3.9 billion). In 2019, companies set up under FDI contributed to 71% of the country’s export revenue, with over 90% of manufacturing exports generated through FDI.

While Vietnam’s FDI and export experience is worth emulating, Bangladesh has a long way to go when it comes to opening up. So, FTAs, bilateral or regional, look like a far cry with our current state of trade restrictiveness (e.g. tariffs are just too high). After the East Asia miracle of the 1970s-80s, and China’s export success over the past 25 years, Vietnam appears to be the new posterchild of export success, but with the distinctive feature of FDI-driven exports. This experience is something for Bangladesh to draw on.

After the East Asia miracle of the 1970s-80s, and China’s export success over the past 25 years, Vietnam appears to be the new posterchild of export success, but with the distinctive feature of FDI-driven exports. This experience is something for Bangladesh to draw on.

On the export front, Bangladesh now faces the dual challenge of post-pandemic export recovery together with getting traction on export diversification. Bangladesh’s trade and FDI regime are calling for a major overhaul if growth and job creation are to resume. Greater trade openness and removal of anti-export bias of policy is a priority. Business-as-usual policies will not be the answer. On the FDI front, clearly Bangladesh must position itself to attract much larger volume of FDI, which must be the export seeking type, to move the needle on export diversification. It is in the national interest for BGMEA and BKMEA (along with BTMA) to welcome FDI in their sectors, without conditions. As more FDI comes into Bangladesh’s leading sector, RMG, there will be spillover effects resulting in export seeking FDI going into non-RMG export production (e.g. footwear, plastics, bicycles, electronics, toys) where external demand is not a constraint because Bangladesh has only infinitesimal shares in the global market. PRI research has shown that competitiveness is not a binding problem, lack of export incentive is. Rationalizing the protection regime will make non-RMG exports more attractive.

Bangladesh needs to ramp up production and export of non-RMG products. Infusion of export seeking FDI is critically needed for this to happen.

This article was the lead article in October issue of Am Cham Journal.

Promito Musharraf Bhuiyan, Senior Research Associate at Policy Research Institute, provided competent research support.