Automobile sector development in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects

By

I. Background and Introduction

The transport sector in Bangladesh is dominated by road transport. According to BBS, In FY 2017, the transport sector accounted for 10 per cent of GDP. This sector is an integral part of the national and international value chain contributing to sustain the production and distribution network both nationally and internationally.

In terms of numbers, cars dominate the total number of vehicles in any country, and Bangladesh is no exception. The car market in Bangladesh is comprised of three types of suppliers: Imports of brand-new cars; Imports of reconditioned cars; and Cars manufactured in Bangladesh

Imports of reconditioned cars from Japan played a significant role in the growth of this sector. According to Bangladesh Reconditioned Vehicle Importers and Dealers Association (BARVIDA), the reconditioned cars supply about 80 per cent of the vehicle needed for this sector. Most international car companies also have their direct distribution networks through domestic dealers as sales of new cars are also increasing steadily. Domestic manufacturing of cars in Bangladesh has been primarily limited to assembling of completely knocked down (CKD) components. Only one public sector company has been assembling limited number of old or discontinued model cars since 1960s with very limited success. Very recently, a number of private entrepreneurs have launched assembling plants using the cover of protective tariff structure. It is yet to be seen how these firms perform in the coming years.

II. An Overview of Bangladesh Car Market, Tariff and Tax Structure, and the Market Size

1. An Overview of Bangladesh Car Market

Transportation plays a very important role in the development of a country. The demand for automobile rises along with the country’s economic development. To meet these demands, Bangladesh has to depend on 3 types of imported vehicles as we yet don’t have a fully operational automobile manufacturing industry.

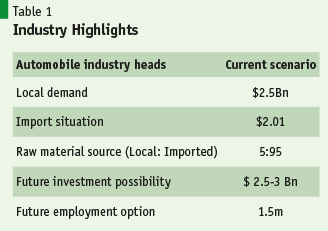

The overall size of the automobile market in Bangladesh is quite modest despite the gains reported in recent years. 95% of the key components and accessories are being imported from abroad, most of the import demand is met through imports. There is future investment possibility in the amount of $2.5-3 billion according to Board of Investment, Bangladesh. However, these projections are not based on detailed market analysis and cross-country experience.

2. Tax and Tariff Structure on Automobiles in Bangladesh

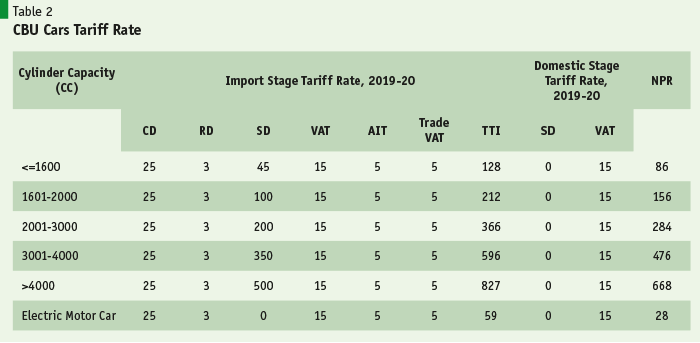

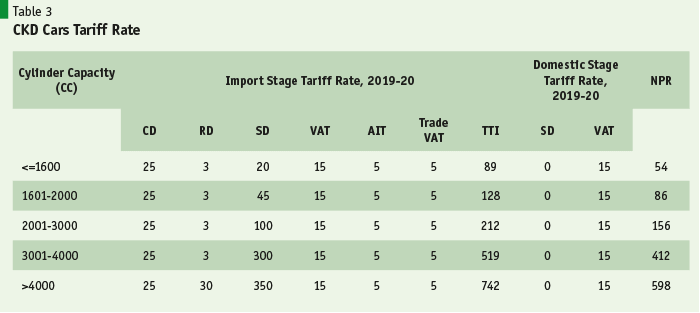

To contain road congestion by making automobiles expensive, and to collect a large sum of revenue through imposition of duties and taxes from car imports, the government has imposed very high duty and tax rates on imported motor vehicles increasing the prices which made them harder to afford even for the upper middle-income households. Most of the taxes are imposed in the form of supplementary duty (SD) levied at rates ranging between 20% to as high as 500% for cars of more than 4000 cc engine capacity. A review of the current duty and tax structures levied on imported cars indicate that the duty/tax rates vary widely in three different ways: (i) depending on whether cars are imported in completely knocked down (CKD) and completely built up (CBU) forms; (ii) depending on the engine capacities of cars (measured in terms of cubic centimetre (ccs) or litres); and (iii) depending on the fuel sources of cars the SD rates are different for electric, hybrid or gasoline/diesel fuel based cars. Present supplementary duties for imported completely built units (CBU) regular, hybrid, and electric car are given in table 2.

In addition to the customs and supplementary duties imposed on imported cars, various other duties and taxes are levied at various rates: Custom Duty at 25% rate, Regulatory Duty (RD) at 3% rate, Advance Income Tax (AIT) at 5% rate, and Trade VAT (TV) at 5% rate are charged to the importers of automobiles at the import stage at the port of entry. In addition to these duties and taxes levied on the cif value of cars at the import stage, VAT is applied at 15% rate at the duty and tax paid value as the base. In total the purchase price of the TK 100 car will be TK 227 in Bangladesh market, a total tax incidence of 127%. This is only based on a low value less than 1600 cc car. The total tax incidence may go as high as 827% for cars with engine capacity above 4000 cc. By any consideration, the overall duty/tax incidence on imported cars is outrageously high in Bangladesh.

On environmental grounds, the SD rate on electric or battery run motor vehicles is completely exempted. However, because of lack of proper ecosystem like charging stations across main highways and in all cities, lack of maintenance and service facilities across the country electric cars are not popular as of now.

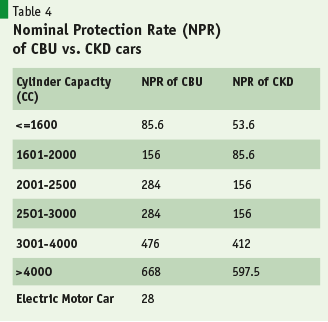

A review of the tax structure indicates that the SD rates in general are very high and at the same time highly progressive depending on the engine capacity of the cars. There are also wide variations between the imported CBU and CKD cars, with a view to provide sizable degree of protection to domestic assemblers of automobiles. The difference in total import-based tax incidences between the CKD and CBU indicate the degree of protection offered to automobile assembly operations in Bangladesh. The last columns of Table 4 shows the Nominal Protection Rate for CBU and CKD cars. A review of the column indicates that the minimum nominal protection offered to the CKD assemblers is 86% for the small cars of less than 1600 CC capacity and the nominal protection is highest for 2000-3000 CC CKD cars.

Anomalies in Current Valuation Practices by the Customs Administration

In the case of re-conditioned cars, the stated principle is to apply the depreciated value as the base for imposing duties and taxes in the same manner and at the same rates as described above. However, in practice at the port of entry the valuation base used by customs officials is the Yellow Book value for new cars instead of the Yellow Book value for the reconditioned car based on the model year. Since Yellow Book values for new cars are generally much higher than the actual Yellow Book value of old cars, the total tax incidence on reconditioned cars increases significantly. For example, in the case of a 2014 Toyota Premio, the additional tax incidence based on yellow book value of new Premio is estimated to be more than Tk. 266, 843 according to BARVIDA. For Toyota Axio 2015 1500 cc model, the corresponding additional tax incidence is estimated by BARVIDA to be Tk. 540,799.

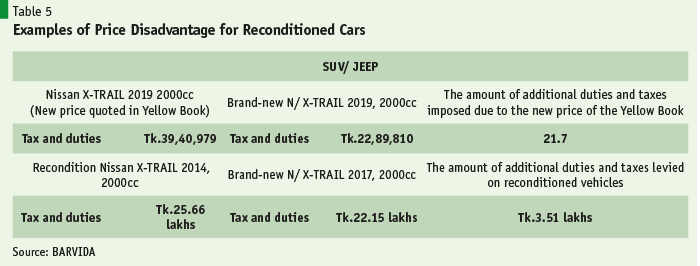

The anomalies in valuation for imported new CBUs and reconditioned cars also lead to situations such that total import stage tax incidence on new cars is lower than the total tax incidence on reconditioned cars. This awkward primarily results from the fact that while the value for reconditioned cars are based on Yellow Book value for new cars, the valuation for new cars are based on importers’ declared value. Total tax incidence on reconditioned Nissan X-Trail 2000 cc 2019 model is Tk. 16.5 lac more than the same Nissan X-Trail 2000 cc 2019 model new CBU (Table 5). Similarly, for a 2000 cc Mitsubishi Outlander 2019 reconditioned model requires Tk. 18.37 lac more in taxes compared with an imported new Mitsubishi Outlander 2000 cc 2019 model. The extent of tax anomalies is such that in many instances the final price of a new car is cheaper than the final price of reconditioned cars of same models.

The extent of tax anomalies is such that in many instances the final price of a new car is cheaper than the final price of reconditioned cars of same models.

Because of the high duty and tax rates, revenue collection from imported automobiles is quite sizable, and was also increasing at a healthy pace with growth in imports of automobiles until FY18. Revenue collection from automobile imports accounted for a sizable part of trade-based taxes and duties collected by the NBR in FY18, and this overdependence has also contributed to continued high rates of duties and taxes on automobiles at the import stage.

The anomalies in the tax assessment and the consequent high tax incidence on reconditioned cars since 2018 has contributed to a marked decline (about 48%) in the number of reconditioned cars in FY19. The decline further accentuated in FY20 with reconditioned car imports in the first half of the fiscal year (July-December 2019) declining to only 4700. The market share of reconditioned cars in total cars registered in Bangladesh also declined significantly since FY18. Of course, the further sharp decline in import of reconditioned cars in the first half of FY20 was also attributable to a general decline in total car demand in Bangladesh due to generally weaker economic activity since the beginning of the fiscal year, well before the devastating impact of the corona virus starting from March 2020.

As the demand for reconditioned cars collapsed following the adoption of discriminatory valuation base for the reconditioned cars, revenue earned from reconditioned cars also collapsed in FY19, and further faltered in the first half of FY20 (Figure 5). The sharp decline in revenue from reconditioned cars in the pre-Covid-19 period essentially reflected the impact of two factors: (i) a general decline in car demand in Bangladesh representing the very high incidence of taxes on all imported cars; and (ii) a general slowdown in economic activity which depressed all kinds of imports including all types of automobiles.

3. The Size of the Car Market in Bangladesh

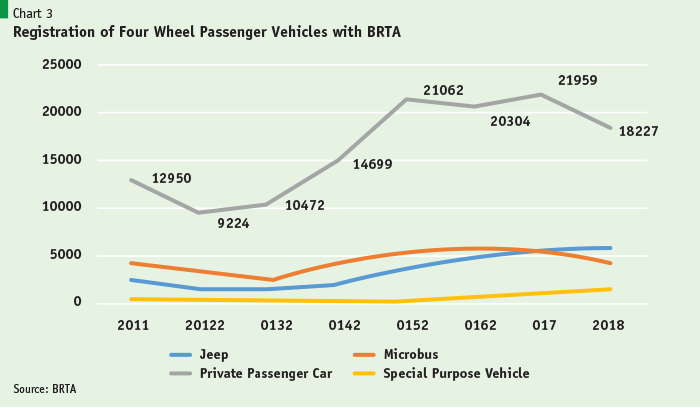

At present, there is a total of 0.36 million private cars in the roads of Bangladesh, which was 0.22 million in 2010. Import of private passenger cars have risen significantly from 9,224 in 2012 to 21,959 in 2017; a rise of 138 percent in 5 years. Sale was mostly prominent during 2015-2017 period. In 2018, a total of 18,227 private passenger cars were registered as per BRTA, which means on an average 50 new cars were hitting the streets of Bangladesh every day.

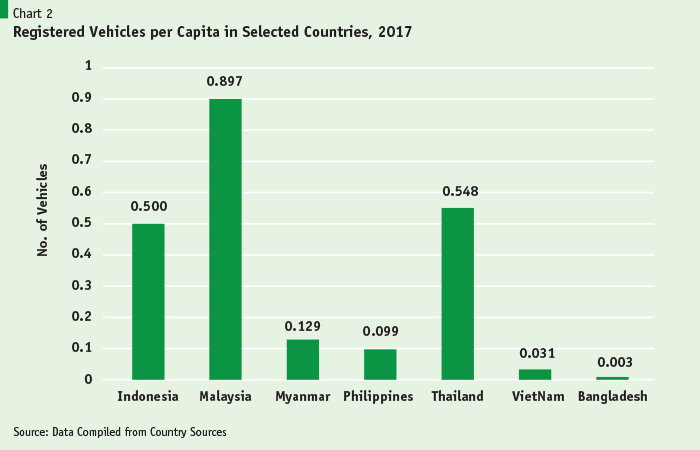

This low number of cars in the streets of Bangladesh is also reflected in the extremely low number of cars per capita in Bangladesh compared with comparator countries. Bangladesh has 3 cars per 1000 population, compared with 897 cars per 1000 in Malaysia. Even country like Myanmar has 129 cars per 1000 persons. In Vietnam car ownership per person was 3 times that of Bangladesh. Of course, per capita income has a lot to do with the ownership of cars in a country and Bangladesh as a relatively low-income country has the lowest per capita car ownership. In addition to this income factor, the extremely low number of car ownership in Bangladesh is a reflection of a number of other factors like: (i) extremely high duty and tax rates imposed on cars; (ii) extremely congested roads and poor quality of roads; (iii) very high maintenance costs due to costly auto parts; and (iv) most families need to hire a driver for driving the car primarily because of unsafe driving condition and the possibility of pilferage if cars are parked in road sides unattended by drivers.

In 2018, a total of 0.42 million vehicles were registered in Bangladesh according to the information posted in the official website of Bangladesh Road Transport Authority (BRTA). More than 98% of the registered vehicles were two-wheeler motor cycles numbering about 395,000. The number of private passenger cars was only 18,000. In line with the slowing economic activity, as reflected in the downward trend of all key economic and financial indicators, sale and registration of cars were also slowing down after 2017.

4. Composition of the Domestic Car Market

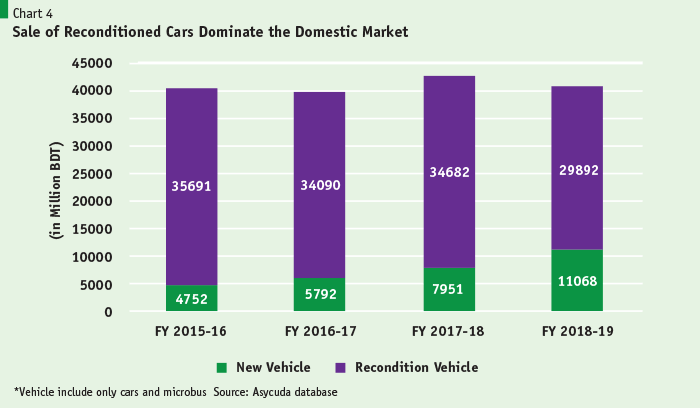

Since the domestic manufacturing base is still very small or almost negligible, almost all domestic demand for cars is met through imports. The domestic car market is dominated by the imported reconditioned cars. Although imports of new vehicles have grown quite rapidly, the total import value of reconditioned cars as of FY19 still stands at 2.7 times that of new imported cars. The ratio however was much more lopsided at 7.5 times in favour of reconditioned cars only a few years back in FY16.

The discriminatory valuation for tax purposes may have contributed to the steady switch to new vehicles.

5. State of Local Automobile Industry in Bangladesh

Because of very small size of the domestic market, absence of international car manufacturers partly because of the small market, lack of domestic sources of raw materials and absence of backward linkages, vehicle manufacturing and assembling industries did not develop in Bangladesh. Supply of automobiles in Bangladesh is largely dominated by import of reconditioned and new vehicles mostly from countries like Japan, China, India and relatively less from the European countries and the USA. Recently, few entrepreneurs emerged with the collaboration of foreign companies like Hino, Mitsubishi, Tata Motors, Ashok Leyland etc. to start assembling of cars, trucks, pickups and buses in limited quantities. Sales of trucks in the country increased significantly because of the boom in economic activity, including supports from the garment and cement sectors as well as easy financing and lower taxes.

A number of small and medium-sized initiatives are underway for automobile assembling. PHP, a business conglomerate based in Chittagong, signed a deal with Malaysian automobile manufacturer Proton to set up an industry with a capacity of manufacturing 1,200 cars per year. The company announced to invest TK 400 crore in the project employing several hundreds of workers with 50 engineers. Furthermore, in 2015 three car manufacturing companies – Zinwa, BMG, & KRW, from South Korea have collaborated with Ena Group to manufacture battery-driven auto car (automobile) in BSCIC industrial estate in Rajshahi city. There will be Lithium battery in the car which will run at least 100 kilometers, charging only once. It will cost around US $18,000 or Tk.1, 200,000.

Based on press reports, a number of other foreign automobile companies have entered into agreements with local entrepreneurs to set up assembling plants. Nitol Niloy Group has outlined plans to launch the first car to be built in Bangladesh, using the technical expertise and financial support of India’s Tata Motors Limited.

It should be noted in this context that, no major international automobile company has yet shown any interest in making a major investment to set up a large size (four-wheeler) automobile assembling plant with major components manufactured in Bangladesh. What we see at present is that some international companies are willing to provide technology support for assembling some old or discontinued models to Bangladeshi investors in the automobile sector. Most major international automobile companies have already invested heavily in the neighbouring India and in nearby countries like Thailand and Indonesia. Their strategy is to serve the smaller car markets like Bangladesh from these large regional production hubs. It is very unlikely that these major international companies will be interested in investing in Bangladesh since the domestic market is too small, there is no ecosystem for the automobile sector including skilled labour force, and absence of an open trading system with good infrastructure to make the investment a part of the Asian value chain. If there were attractive export potentials from Bangladesh to regional countries—which is a far cry in the absence of the related ecosystem and restrictive and inefficient trade facilitation—some international automobile companies might have been interested in investing in JV or fully owned plants in Bangladesh.

6. Automobile Regulation

According to the regulation of Bangladesh government, import of reconditioned cars, jeeps, microbus, minibus including other old vehicles and tractors are allowed. In Bangladesh, imported vehicle should not be more than four years old. Imports from Japan should be JAAI (Japan Auto Appraisal Institute) certified. In Bangladesh, a used vehicle taxes are levied on vehicles when imported. Only Diplomats and Parliament Members (MPs) get duty free import of one new or old vehicle in Bangladesh.

The automobile sector in Bangladesh is growing with its economic momentum, but still remains quite small by international standards. An extremely high tax and tariff structure applied on imported vehicles has created business opportunities for establishing domestic automobile assembling, but questions remain about the viability of these domestic ventures led by local firms with dubious foreign partnership. Questions remain whether the market size is large enough and the partnership arrangements are with reputed large global car manufacturers on terms conducive for ensuring at least 30% domestic value addition.

In the government’s policy guideline emphasis has been given on efforts to develop trading companies gradually focusing on assembling and manufacturing units, like Semi-Knocked Down (SKD), Complete Knocked Down (CKD) and locally Complete Built Unit (CBU). A strong preference has been given to the favoured development of the government’s current assembling units along with more private investment in motorcycle manufacturing and heavy vehicle assembling.

As the environmental concern is high on the agenda, the country should have its priority right. Western countries are in a race against time to bring out their electric cars on the road. Such initiatives have had moderate success so far. But it can reasonably be expected that given the breakthroughs in electric car technology that has already taken place and the enhanced completion among major automobile and technology companies in the coming years, will reshape the automobile sector fundamentally. The new generation electric cars and related infrastructure and ecosystem will replace the current automobile production technology and offer emission free electric cars at competitive prices with safety and reliability. Bangladeshi manufacturers may consider leapfrogging to the future electric car technology with zero emission and not starting its journey at this late stage on the manufacturing traditional liquid fuel-based cars.

III. Motor Vehicle Policy—International Experience and Relevance for Bangladesh

1. MVP—Bangladesh Situation

Bangladesh does not yet have a comprehensive national motor vehicle policy (MVP), but the government has drafted an Automotive Sector Development Policy (ASDP) and conducting consultations with the stakeholders. The draft ASDP aims to increase production of commercial vehicles (buses, trucks and minibuses) also promote production of passenger vehicles (saloons, station wagons, Sports Utility Vehicles (SUVs)), and motorcycles through:

(i) Providing incentives to manufacturers/assemblers based on different levels of vehicle breakdown (Knockdown), with incentive levels linked to: local value-addition; degree of technology transfer; improvement in level of expertise; level of foreign exchange earnings; strengthening of manufacturing value chain; developing linkages within the industry; and investment in R&D.

(ii) Promotion of local entrepreneurs engaged in motor vehicle component manufacturing in Bangladesh and encouraging and facilitating sub-contracting amongst established assemblers and the local SMEs.

(iii) Hastening progression and phased advancement from SKD to CKD.

The draft ASDP proposes a number of strategies to achieve the objective stated above. These include:

Strategy 1: Promotion and Development of Local Assembly

Strategy 2: Development of Automobile Market

Strategy 3: Development and Promotion of Local Parts/ Components Production

Strategy 4: Used Car Import Phase-out Plan

Strategy-5: Strengthening of Vehicle Registration and Inspection (Fitness Test) System

Strategy 6: Promotion of R&D and Development of Design/ Testing

Strategy 7: Formulation (Harmonization) and Enforcement of Automobile Standards (safety, quality, emission, etc)

Strategy 8: Development of Industrial Human Resources

Strategy 9: Improvement of Investment/Business Climate

2. An Evaluation of the ASDP

The initiative taken by the government through the ASDP is welcome, although it is still indicative in many areas and would need to be detailed out a lot in consultation with all relevant stakeholders. There could be an ASDP in Bangladesh, but it must cover all three major market segments: domestic production along with imports of CBU and reconditioned cars. The 9 strategies identified in the draft ASDP are mostly appropriate, except for Strategy number 4 on Used Car Phase out Plan. The phase out plan under strategy 4 is a fundamental violation of ensuring a competitive market and also directly contradicts with the Strategy 1. The strategy 1 clearly states that the policy will aim at “development of manufacturing capabilities as opposed to mere assembly without giving undue protection; ensuring balanced transition to open trade; promoting increased competition in the market and expanding choice/options to the Bangladeshi consumers.” It also states that “Used vehicles imported into the country would have to meet environmental requirements as per BRTA laid down specific standards and other criteria for such imports.” This contradiction should be resolved by deleting strategy 4 out of the draft ASDP.

The draft ASDP does not take into account the important issue of very limited domestic market size and the positioning of major international car manufacturers in the regional countries. As discussed earlier, the market size in Bangladesh very is very small at less than 30,000 units which is less than 4% of Thai domestic market. Since most global automobile companies are already well positioned in countries around Bangladesh—particularly in India, Thailand, China, and Indonesia—investment in the small domestic market of Bangladesh will not be attractive. Accordingly, while keeping the option for FDI driven automobile sector development as an option, the draft ASDP should have a balanced and realistic approach with regard to automobile sector in Bangladesh. The potential investors would need to have both external and domestic markets in their focus.

Under no circumstances the companies with domestic assembling should be given excessive protection to promote an inefficient and largely CKD or SKD driven plants what we call screw driver type automotive industry. This type of highly protected investment does not create the necessary value addition in the domestic economy—in some cases the domestic value added may be negative because the CBU units may cost less than the cost of cars based on CKD or SKD type screw driving activity in the name of automotive industry.

If Bangladesh really wants to have a vibrant domestic car industry it should be export oriented and forward looking. Most countries in the world are in the process of phasing out combustion engine based polluting car industry, and have announced plans to become completely carbon emission free cars—electric or solar—before 2040. This is not the time for Bangladesh to set up combustible engine (petroleum run) based automobile industry when the rest of the world is getting out of this technology. There is also the risk that international automakers will relocate their old or phased out plants for setting up an industry in Bangladesh under heavy protection. In any event, at this juncture Bangladesh should be forward looking and go for new generation emission free car industry with a focus on the global and regional export markets.

Most countries in the world are in the process of phasing out combustion engine based polluting car industry, and have announced plans to become completely carbon emission free cars—electric or solar—before 2040. This is not the time for Bangladesh to set up combustible engine (petroleum run) based automobile industry when the rest of the world is getting out of this technology.

The ASDP does not go into the details of vehicle emission standards, which it should focus on. As discussed below, vehicle emission standards are an integral part of MVP in almost all countries worth mentioning. The following section briefly discusses the state of emission control in major economies and regional countries.

3. Vehicle Emission Standards and Automobile Policies

In the MVPs of most countries, Vehicle Emission Standards play an important role as part of the countries’ environmental and clean air initiative. Major economies like the EU and the USA have established their respective vehicle emission standards depending on their intensity in drive for cleaner air. Within the USA, many states have also established their own emission standards which are tighter than the Federal Government standards—the emission standards of the state of California being the most stringent one, which in many ways establishes the emission standards for the rest of the USA. No major car companies can ignore the emission standards of California and operate efficiently in the US market. Outside the USA, the most commonly followed emission standard is the Euro Standards or its equivalents.

EURO STANDARD: Since 1992, European Union regulations have been imposed on new cars, with the aim of improving air quality – requiring vehicles to meet a certain Euro standard when they are manufactured. The first EU-wide standard – known as Euro 1 made catalytic converters compulsory on new cars, effectively standardizing fuel injection. Since then, there have been a series of Euro emissions standards, leading to the current Euro 6, introduced in September 2014 for new type approvals and rolled out for the majority of vehicle sales and registrations in September 2015. The regulations, which are designed to become more stringent over time, define acceptable limits for exhaust emissions of new light duty vehicles sold in the EU and EEA (European Economic Area) member states.

The EU has determined that air pollutant emissions from transport have substantial contribution to the overall state of air quality in Europe with industry and power generation being the other major contributors. The aim of Euro emissions standards is to reduce the levels of harmful exhaust emissions

In Bangladesh, Vehicle Emission Standards is based on Euro 2 implemented nationwide from July 2014. Euro 3 standards were implemented from July 2014 in Dhaka and Chittagong and planned nationwide for July 2019. The authorities also planned for Euro 4 standards in Dhaka and Chittagong from July 2019. For importation purpose Euro 2/Euro 3 standards are in effect since July 2014. Used car imports are subject to a cap of less than 4 years old, while there is a ban on used motorcycles, three wheelers, and commercial light duty and heavy-duty vehicles effective July 2014. The low emission control standards allow for importation of new cars from regional countries like India, Thailand and Indonesia which are currently at Euro 4 standards. In contrast, reconditioned vehicles from Japan and European countries generally meet Euro 5 or better standards.

IV. International/Regional Experience with Development of Automobile Manufacturing and Lessons for Bangladesh

A review of international and regional experience with automobile manufacturing indicates both stories of successful and unsuccessful efforts. Most countries in the East and Southeast Asia and South Asia regions started their journey with automobile industry during 1950s and 1960s with investments by international automobile companies themselves or through their joint venture partners. The approaches adopted by different countries were somewhat different leading to very different outcomes. Large economies like China and India have been successful primarily because of their very large domestic market size. For relatively mid-sized economies, Thailand clearly had a very successful outcome in terms of production and export of automobiles, which attracted all major international car makers to these markets. In contrast, Malaysia despite very strong and costly public sector support, failed to develop an efficient and dynamic automobile industry.

ASEAN Experience: The signing of the AFTA trade agreement among the ASEAN countries had significant implications for the automobile industry in South East Asia markets. By 2010, all members were obliged to completely eliminate tariffs on goods manufactured by other member countries. Thailand made the best use of this market opening, while Malaysian car makers were unable to capitalize on the opportunity of the ASEAN market. Malaysia neither had the largest domestic market for motor vehicles nor the top production base. Thailand and Indonesia were more promising markets with larger population, rapidly growing middle class, and lower penetration. Japanese automobile manufacturers, being historically the largest producer in the ASEAN region, were in the best position to exploit the ASEAN market opening and commanded lion’s share of the sales. By 2008, well before the ASEAN cross border market opening, out of 2 million vehicles sold in the ASEAN countries, Japanese manufactures contributed 1.72 million units, a commanding 86% of the market share in the region.

Malaysia was the only one among the South-East Asian countries to have its own nationally owned brand. The others chose to develop their automobile industry by attracting foreign automakers to manufacture in their country. As stated in the 2011 annual report of Proton, its modest exports were mainly to non-ASEAN countries like the UK, Middle East, Australia, China and Iraq as customers in the ASEAN market were opting for locally or regionally made higher quality foreign brands which were introducing various new models every year. The country experience with development of automobile industries in the South Asia and South-East Asian countries—based on the lessons learned from the winners and losers—points to a number of lessons for countries like Bangladesh.

Thai Experience: Thailand is the most successful country in developing its automobile sector for a developing country with relatively mid-sized economy (GDP of $505 billion in 2018), moderate size population (69.4 million in 2018) and GDP per capita of about $7,274. Thailand’s automobile sector was driven by both exports and domestic demand and it was supported by an ecosystem of vast network of domestic small and medium industries engaged in auto parts and accessories manufacturing.

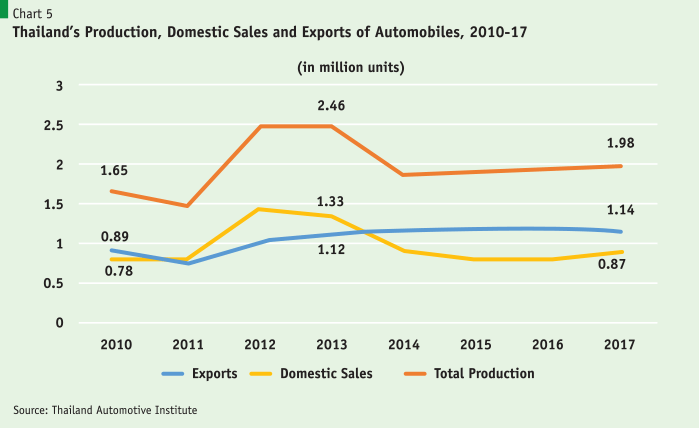

The rapid growth of the industry in the 1990s was the direct result of two factors: (i) the expansion of Japanese car makers and auto parts to Thailand in 1985 as a result of an appreciation on the Yen as part of the Plaza Agreement among the G-7 countries; and (ii) the deregulation of the industry in 1990 by the Thai government followed by the removal of the Local Content Requirement regulation in the year 2000. Thailand had the potential to be an export base and hence large automobile manufacturers such as Mitsubishi, Toyota, Auto Alliance, GM and Isuzu decided to use Thailand as their export base. The production capacity and volume increased massively since then reaching 2 million units by 2010. Currently about 60% of domestic production is destined for exports and domestic demand accounts for more than 40% of total production.

Thailand is not just a place where carmakers assemble their products. Most of the parts also come from local manufacturers. It has high localization economies of scale. The knowledge gained from foreign manufacturers such as Toyota, Isuzu, Honda and Ford, led to the expansion of the auto parts industry, hand in hand with supporting government programmes. In addition to supplying most auto parts to the domestic industry, Thailand exports parts worth US$ 5 billion on average. The Thai automobile and auto parts industry accounts for nearly 12% of its economic growth and employs 550,000 people.

Auto manufacturers and investors in the sector benefit from Thailand’s Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with the other countries. Currently, there are six FTAs with New Zealand, India, Australia, China and the 10 ASEAN member countries. This provides auto manufacturers with the opportunity to expand their supply chain and gain competitive advantages in the import of production inputs by the reduction of import duties and customs fees. It also allows them to protect their investments and intellectual property, as well as expanding business opportunities.

The structure of the Thai automotive industry ecosystem provides very interesting picture. Large scale enterprises comprising automobile assemblers (14 in 2014) and motor cycle manufacturers (8 in 2014) provided employment for about 100,000 persons. These large enterprises are largely foreign and joint ventures. In the next tier (Tier 1) there are more than 700 mid-sized companies, half of which are fully foreign owned and the remainder either jointly owned or fully owned by Thai companies. At the bottom of the pyramid there are more than 1700 small and medium enterprises, comprising local suppliers of auto parts and accessories, which are wholly owned by Thai national entities. Most jobs were created at the bottom tiers, with Tier 3, Tier 2, and Tier 1 together accounting for more than 80% of the jobs created in the automobile sector.

Malaysian Experience: In contrast to the Thai model, Malaysia, a slightly smaller economy in terms of GDP ($358.6 billion in 2018), but with much smaller population (31.53 million in 2018) and much higher per capita GDP of $11,373 in 2018 opted for the Korean model of developing its own automobile industry with massive public sector support in the form of subsidies and high degree of protection for the automobile sector. Malaysia always had a relatively large domestic market for its population size, given the relatively high per capita income. From the mid-80s till 2010, the Malaysians reliance on cars mirrored that of much wealthier countries such as the USA and Luxembourg with sale of more than 600,000 vehicles in 2010 alone. In that year, Malaysia had the largest passenger car market in the ASEAN. Malaysia ranked third among vehicle ownership in the world, with on average, one in four Malaysians owning a car.

The combined market share of Perodua and Proton, the two largest manufacturers, still accounts for more than 60% of the total sales of passenger vehicles in Malaysia in 2018. Malaysia tried to develop the export market through marketing of Proton to the Middle Eastern, South Asian and UK markets. But despite repeated efforts, export performance was dismal. Proton entered the UK market in 1989 with sales reaching a peak of 15,000 (1992) but it fell steadily to 1,518 (2008). This was due to British demand for higher quality and safety standards, local competition and inadequate after-sales service. Proton exports were small with total exports below 25,000 units in 2009/10. Proton also lost out its domestic market in a big way to its home-grown competitor, Perodua.

South Asian and Indian Experience: In our region, India has developed a large automobile sector following its economic liberalization in early 1990s, and supported by foreign investment and technology which flowed into the Indian automobile industry lured by its huge domestic market size and positive economic growth outlook. Although India started its public sector supported and private sector-led automobile industry soon after its independence, it could not develop the sector and the market was relying primarily on large domestic conglomerates producing old models with outdated technology. The Indian cars of 1960s and 1970s were heavy, extremely fuel inefficient, and were of extremely limited models for buyers to choose from. The industry started to change primarily with the joint venture investment between Maruti and Suzuki to produce fuel efficient sub-compact cars for the massive Indian emerging middle class. With market liberalization beginning in early 1990s, almost all major international brands started establishing their production and assembling plants in India lured by its vast and rapidly growing middle class. India today has a vast automobile sector offering most major global brands and a vast range of models for its fast- growing consumer base.

In South Asia, Pakistan—despite its very early start–only had a limited success primarily focused on the domestic market with private sector joint ventures. As we all know, Bangladesh’s experience with state owned Progoti Industries was essentially a failure with total assembling of 1500 cars since the country’s independence in 1971.

V. Key Elements of a Rational Motor Vehicle Policy for Bangladesh and Recommendations

The draft ASDP prepared by the Ministry of Industries (MOI) is a step in the right direction. However, what Bangladesh needs a much more holistic approach to automobile sector development by preparing a MVP. A rational MVP for Bangladesh must take into account the experience of countries in the region and the global trends in automobile technology and environmental considerations. In the Bangladesh context, the MVP must have the following characteristics: (i) harmonization of the MVP with the objectives of national and particularly urban transport policy; (ii) a right balance between consumer interest and development of domestic automobile industry; (iii) enhanced focus on automobile emission standards since air quality in Dhaka and other major cities in Bangladesh are considered to be extremely unhealthy; (iv) characteristics of Bangladesh market for cars, its demand potential and implications for future demand outlook; and (v) developing an ecosystem for the automobile sector to improve the servicing of automobiles and to ensure viability and sustainability of the domestic assembling/manufacturing activity. What we are proposing is to broaden the scope of the draft ASDP and incorporating much more details on various issues stated above to move to a comprehensive MVP like most other countries of the world. As part of the holistic approach, the proposed MVP should focus on the following important issues.

Harmonization of MVP with Urban and national transport policy: Almost all urban centres in Bangladesh, where most cars are plying, are already suffering from road congestion primarily due to inadequate space for vehicular movement. Road networks in urban centres in Bangladesh is highly inadequate in terms of standard proportion of road surface relative to the geographical size of the city and also in terms of urban planning perspective. Investment in new roads has been extremely inadequate and despite a sharp increase in population in all urban centres–large, medium or small—attention to urban transportation has been minimal. The result is the emergence of a multimodal transportation system—including old carts pulled by humans, rickshaws and rickshaw vans, two-wheeler motor cycles, three-wheeler public transportation, cars of all kinds, and cargo carriers from small pickup trucks to 18-wheelers. Traffic is generally managed by hand despite deployment of sophisticated traffic light systems. There is no proper road sign system, no designated parking spots and public parking places, no well-designated bus stoppages, and no enforcement of pedestrian crossing rules. All these key issues need to be addressed as part of improved flow of traffic under the constrained road conditions. If traffic flows on city streets are not improved through these internationally practiced systems, there should be very stringent limits on the total number of cars in the cities. Only with better in-city traffic management the number of cars can be allowed to increase significantly in Bangladesh cities. Investment in public transport system including rapid bus transit system, elevated and underground metro rail system, efficient commuter railway system, systematic use of some key waterways will be the way to manage public traffic in Bangladesh cities.

Establishing the Emission Standards for Bangladesh:

Bangladesh needs to:

1. Define the emission standards that will be consistent with at least Euro Standards V by 2022, with a target of harmonizing with the most stringent global standards or one notch below by 2030, across all vehicle segments. This roadmap will in turn enable the industry and support agencies to define the requirement of technologies, testing facilities, skill development and plan long-term investments.

2. Develop a roadmap for reduction in CO2 emissions through Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations for domestic automobile industries and also for imports. Roadmap should define corporate average CO2g/km targets for all passenger vehicles manufactured or imported from 2022 onwards. The vision will be to match CO2 targets set by developed countries by 2025-2030 in phases.

3. Introduce economic penalties for manufacturers and importers that do not meet corporate average targets in the case of domestic manufacturing or at least Euro Standard V for all vehicle imports.

4. Introduce a composite number/index comprising size of engine, fuel efficiency (reflecting the fuel mix as well), and emissions based criterion for vehicle taxation purpose whether domestically manufactured or imported as CBU or reconditioned.

5. Rationalize the structure of taxation (comprising VAT, supplementary duty, and other duties and taxes) for automobiles on the basis of the proposed composite number/index. Currently the taxation structure is based on the size of engine and fuel mix (such as hybrid or electric vehicles), but does not take into account the fuel efficiency in terms of energy equivalents and there is no consideration for emissions-based criteria. To achieve this objective the following actions will be needed:

• Replace the current classification criteria focusing on engine size with a composite criterion based on engine capacity, vehicle length and CO2 emissions

• Use engine capacity to deal with fuel consumption, use vehicle length-based classification to target reduction in vehicular congestion, and deploy CO2 emissions based classification aligned with the overall vision of green mobility and reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

• Define thresholds for engine size, length and CO2 emissions with the objective of neutralizing impact on tax revenue

• Monitor and review the thresholds based on market evolution and the target for increasing the share of greener vehicles.

The MVP should aim to achieve harmonization of standards

The MVP should aim to achieve harmonization of standards over the next five years by:

• Defining a roadmap for harmonizing key standards and testing methods with global benchmarks

• Upgrading agencies like Bangladesh Road Transport Authority (BRTA) in line with the harmonization plan to develop capabilities at par with global testing and certification agencies

• Evaluating accession to the UNECE WP.29 1958 agreement within the next five years, which will eliminate a major technical barrier to trade

The MVP should implement measures to increase exports of vehicles and components (auto parts). This is particularly important for Bangladesh given its very small domestic market.

• Conducting a detailed study of business environment, procedures, infrastructure etc. for connecting Bangladesh with the Asian automotive value chain

• Identifying and initiating trade agreements with countries having attractive markets for auto parts from Bangladesh

Prepare a forward looking green mobility roadmap for Bangladesh

• Finalize a technology agnostic green mobility roadmap through evolution of emission regulations

• Define the long-term roadmap for incentives and infrastructure investments for green mobility

• Drive demand by expediting adoption of green mobility in the public domain including:

> Mandating minimum share of green vehicles among new vehicles purchased by central and state government agencies and municipal corporations

> Using the Government e-Marketplace (GeM) portal to aggregate all green vehicle orders with standard specifications over three months and enable bulk procurement

• Plan an advanced and extensive green mobility infrastructure network

• Conduct a detailed study on requirement of public infrastructure for green vehicles; and

• Based on the study, define a national plan for establishment of public infrastructure for green vehicles

Ensure upgrades of test facilities in alignment with technology roadmap

• Establish an investment and upgrade plan of test facilities in Bangladesh, aligned with overall industry roadmap. Long-term outlook will enable research and testing agencies to plan and setup capabilities for development and testing at the right time.

There are many other areas which should also be part of the MVP. These include skill development and training equipment; scaling up of indigenous R&D with commercially viable innovations and associated incentives; developing capabilities and technology improvement in identified areas for auto component manufacturing; implementing an outcome-based funding scheme for Industry-Academia collaboration; proposing and implementing tax exemption on different levels of R&D expenditure; and offering fiscal support for technology improvements in auto components sector. All these areas have been contained in the draft ASDP and could be incorporated to the expanded MVP from the draft ASDP.

VI. Concluding Observations

This article provides an overview of the car market in Bangladesh and makes specific recommendations for its sustained growth. It identifies six important elements of the car market in Bangladesh. These include: (i) characteristics of Bangladesh market for cars and other vehicles, their demand potentials and implications for future demand outlook, and the factors contributing to the very limited market size and falling demand for cars; (ii) a comprehensive review of the valuation, duties and taxes, and subsidies with a view to rationalizing them to support domestic demand for cars; (iii) a right balance between consumer interest and development of domestic automobile industry, which will entail developing domestic automobile industry without undermining competition among all players in the market and limiting the degree of protection for domestic assemblers within internationally acceptable range; (iv) enhanced focus on automobile emission standards since air quality in Dhaka and other major cities in Bangladesh are considered to be extremely unhealthy and in this context Bangladesh needs to articulate a policy to achieve certain ambitious emission standards by target dates; (v) harmonization of the automotive sector strategy or MVP with the objectives of national and particularly urban transport policy; and (vi) developing an ecosystem for the automobile sector to improve the servicing of automobiles and to ensure viability and sustainability of the domestic assembling/manufacturing activity. Any strategy for development of the automobile sector in Bangladesh must include a comprehensive examination of all these six key issues which are central to any automobile sector development strategy. Such a holistic approach to automobile sector development would be much broader in scope than the current draft ASDP, and may be appropriately termed as the Motor Vehicle Policy (MVP) of Bangladesh.

In this context, we must also note that the current draft ASDP is proposing a wrong strategy in certain aspects. It is primarily built on banning import of reconditioned vehicles and thereby giving the potential assemblers an opportunity to exploit the domestic market by charging the consumers very high prices. This will significantly reduce competition, which is the core of any dynamic automobile industry. Execution of this policy of phasing out import of reconditioned cars will invariably create a rent seeking industry with captive consumers forced to buy inferior cars at high prices. We are not aware of any respectable country which completely bans import of reconditioned cars to build an unviable and inefficient domestic automobile industry.

The protection regime in Bangladesh should be consistent with the objectives stated above and should foster development of all three components of the automobile industry: domestic production of CBU, SKD and CKD; imports of CBU; and import of reconditioned cars. As shown above, domestic assemblers of CKD and SKD are already enjoying very high degree of protection. This degree of protection must not be increased further, and should be reduced in the interest of consumers under the new policy. If there is any serious international firm interested to set up a full-fledged car industry in Bangladesh, the current tariff structure and incentives are already more than adequate when compared with countries having successful and dynamic automobile industry. Banning of all reconditioned cars must not be part of any strategy to encourage them to build factories in Bangladesh. The foreign or joint venture firms should use lower cost Bangladeshi labor and make them skilled to build cars at competitive prices for sale in the domestic and foreign markets and should not depend on high levels of protection as envisaged in the draft ASDP. Prevailing anomalies in the valuation base—for reconditioned and new CBU imports–for duty and tax purpose should be reviewed and rationalized.

The MVP should aim to develop the whole automotive sector and the related ecosystem including promotion of domestic auto parts industry. The example of Thailand, as shown in the structure of Thai Auto industry, demonstrates the kind of ecosystem and production structure Bangladesh should aim. Ways must be found to join the Asian auto industry value chain—which will require transfer of technology, FDI, a highly efficient border control and seamless flow of components through domestic ports and airports. Joining the Asian automobile value chain would entail air shipment time to anywhere in Asia to be guaranteed within 24-48 hours for high value auto components.

Emission control is always an important and integral part of MVP in all countries. All major cities in Bangladesh suffers from vary bad air quality and one way to address this is enforcement of strict emission control standards for automobiles. The draft ASDP has some marginal reference to the emission standards but does not go into the details and does not establish benchmarks for achieving high emission control standards in Bangladesh. For all cars—domestically produced or imported–Bangladesh should establish EURO Standard V and above effective from FY22, and strive to achieve higher standards like EURO Standard VI within the next 3-5 years.

Bangladesh also needs a Green Vehicle Strategy. The strategy should include a green mobility road map as part of MVP, including achieving a minimum and steadily growing share of green vehicles over time. This strategy should also contain plans for preparing green mobility infrastructure.

If Bangladesh really wants to have a vibrant domestic car industry it should be export oriented and forward looking. All incentives should be given to manufacturing facilities to promote automobile and auto part exports, by ensuring complete application of “zero-rated” principle for the exports. Zero-rated policy implies zero incidence of domestic taxes and duties on imported components for domestic processing of exported automobile related products. Only new models and technologies should be encouraged to enhance export prospects. Use of outdated technology and production of old models should be strongly discouraged through partial or full withdrawal of incentives.

Bangladesh automotive sector strategy or MVP should be forward looking. Most countries in the world are in the process of phasing out combustion engine based polluting car industry, and have announced plans to transform automobile industry to produce completely carbon emission free cars—electric or solar—before 2040. This is not the time for Bangladesh to set up combustible engine (petroleum-run) when the rest of the world is getting out of this technology. There is also the risk that international automakers will relocate their old or phased out plants for setting up an industry in Bangladesh. In any event, at this juncture Bangladesh should be forward looking and go for new generation emission free car industry with a focus on the global and regional export markets.

This is not the time for Bangladesh to set up combustible engine (petroleum-run) when the rest of the world is getting out of this technology. There is also the risk that international automakers will relocate their old or phased out plants for setting up an industry in Bangladesh.

Harmonization of ASDP/MVP with Urban and national transport policy. Currently there is very limited proper road sign system, designated parking spots, well-designated bus stoppages, and no enforcement of pedestrian crossing rules. All these key issues need to be addressed as part of improved flow of traffic under the constrained road conditions. If traffic flows on city streets are not improved through internationally practiced systems, there will be very limited scope for increasing domestic demand for cars in the cities—only with better in-city traffic management the number of cars can be allowed to increase significantly in Bangladesh cities. Investment in public transport system including rapid bus transit system, elevated and underground metro rail system, efficient commuter railway system, systematic use of some key waterways will be the way to manage public traffic in Bangladesh, reduce road congestion and increase number of cars in city streets. Before aiming to achieve domestic production and sales to levels in the range of 100,000-300,000 per year, the authorities should do a comprehensive analysis of traffic flows and congestions in urban and national road system and how to alleviate congestion problem and increase average speed of vehicles in cities and national highways.

If traffic flows on city streets are not improved through internationally practiced systems, there will be very limited scope for increasing domestic demand for cars in the cities…

Finally, the incentive structure for the automobile sector in Bangladesh should be WTO compliant. We must caution that after Bangladesh’s graduation from LDC status in 2024, WTO will not allow Bangladesh to ban import of anything internationally tradable unless those are socially undesirable like arms and addictive drugs. Bangladesh must engage with economic regions like the EU and ASEAN or with countries like India and China to conclude bilateral preferential trade agreements in the post-graduation period. Those countries would not be interested to engage in bilateral preferential trade negotiations with Bangladesh if we maintain very high tariff and quasi tariffs on their products or ban import of their vehicles into Bangladesh.

Bangladesh must engage with economic regions like the EU and ASEAN or with countries like India and China to conclude bilateral preferential trade agreements in the post-graduation period. Those countries would not be interested to engage in bilateral preferential trade negotiations with Bangladesh if we maintain very high tariff and quasi tariffs on their products…

Overall, what we really need is a forward looking export focused strategy aiming to establish a competitive car industry which would be environmentally friendly and in the best interest of our citizens/consumers.