Current State of the Social Protection System in Bangladesh

By

Overview and background

Bangladesh has a strong tradition of caring for the poor and the vulnerable. The need for strengthening this tradition with formal publicly-funded support programs was reinforced by the hard lessons of the 1974 Famine and the floods in the 1980s. The fight against hunger and strong commitment to poverty reduction are now core elements of economic and social policy making in Bangladesh. Yet, a coherent and systematic approach to social protection did not happen until very recently. Over the years since the 1974 Famine, a multitude of small safety net programs have emerged, mostly concentrated in the rural areas, to fight hunger and poverty. Many of these programs were developed through donor assistance. Resource commitments were also made from the national budget, partly as a continuation of these donor-funded schemes.

In FY2015, there were a total of 145 safety net programs involving Taka 308 billion (2% of GDP) and administered by some 23 Line Ministries /Divisions with almost no coordination (Government of Bangladesh 2015). The programs were a mix of cash transfers and in-kind benefits involving some 80.4 million beneficiaries, which is a gross number because it does not net out beneficiaries who receive multiple program benefits. The largest share of spending accrued to the civil service pension (25%) accounting for only 0.5% of the total beneficiaries. The remaining 75% the safety net scheme resources were distributed to the 99.5% of the beneficiaries spread over 144 other programs. As a result, the average amount of benefit from each program and the average total benefit per family were very low.

A key objective of the social security program in Bangladesh is to focus these expenditures on the poor. Yet, the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2010 showed that only 35% of the poor families reported receiving any government-funded social security benefits. On the other hand, some 40% of the beneficiaries were non-poor. Program administrative costs were high and there were reports of considerable leakages. The combination of large exclusion and inclusion errors, leakages and high administrative costs sharply lowered the poverty impact of social security spending. Furthermore, there was no centralized database of beneficiaries and no systematic monitoring and evaluation of program implementation either at the individual program level or for the entire social security program.

Social security reforms and adoption of the National Social Protection Strategy

Faced with these tough concerns, in 2015 the government decided to adopt a major reform program that sought to overhaul the entire social safety net program into a modern social protection system. This was done through the formulation of the National Social Security Strategy (NSSS) that was adopted on 01 June 2015 (Government of Bangladesh 2015).

The features of the NSSS are:

• Took a strategic approach to social security by advocating the consolidation of the multitude of small and often overlapping schemes into 7 core Life-Cycle based schemes.

• Advocated the modernization of the social protection system by the introduction of employment-based social security programs including social pensions and unemployment insurance.

• Called for substantial reform in beneficiary selection and program administration that uses modern ICT-based solutions, with a view to reducing transaction costs and eliminating leakages.

• Advocated the expansion of coverage to the urban poor and the national non-poor vulnerable population.

• Called for conversion of all programs to cash-based.

• Recommended the phasing away of many small schemes that did not fit into the core Life Cycle-based consolidate programs and did not serve a useful purpose in terms of benefitting the poor and the vulnerable.

• Advocated the establishment of an on-line grievance redressal system.

• Called for a strong M&E effort at both the individual program and at the full NSSS level.

The adoption of the NSSS was a major breakthrough in social policy making in Bangladesh. It was intended that the first phase of the NSSS implementation will happen over FY2016-FY2020, to roughly coincide with the implementation of the Seventh Five Year Plan (7FYP). The 7FYP integrated the NSSS as a critical policy for reducing poverty and lowering income inequality.

Track record of implementation of NSSS

Available evidence suggests the implementation of the NSSS in the first 5 years (FY 2016-FY2020) since adoption in June 2015 has been patchy and weak. The Government had assigned the NSSS coordination and implementation monitoring role to the Cabinet Division. There was a long delay with startup of this implementation and monitoring role. Subsequently, with donor assistance, a formal NSSS Implementation Action Plan was adopted in 2018 (Government of Bangladesh 2018). This Action Plan is comprehensive and if these actions are implemented well it should help considerably in making progress with NSSS despite the time lost. The Action Plan set out a two-phased approach to the implementation of the NSSS: phase one comprising FY2016-FY2021 and phase two comprising FY2022-FY2026.

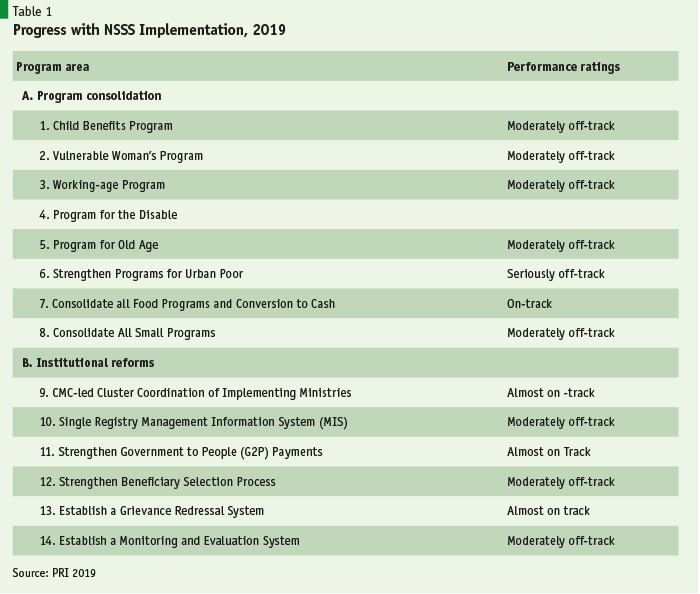

The most systematic and comprehensive review of the implementation of the NSSS and the NSSS Action Plan is done by the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI 2019). In addition to providing a detailed review of implementation progress by each area of reform proposed in the NSSS, the Review uses a quantitative approach to assess NSSS implementation progress based on assigning scores to the measurable indicators of progress identified in the NSSS Action Plan. A rating of “on-track” is assigned if all indicators are met; “almost on track” if substantial progress with the implementation of performance indicators is achieved; “moderately off-track” if progress is made in some indicators but majority is lagging behind; and performance is rated “seriously off-track” if little or no progress is made with implementing the indicators.

The performance assessment distinguishes between (i) progress with program consolidation; and (ii) progress with institutional reforms. The ratings are summarized in Table 1. The program consolidation monitoring involves 86 indicators, of which 20 were on-track, 12 were almost on-track, 11 were moderately off-track and 37 were seriously off-track. Institutional reforms monitoring involves 50 indicators, of which 14 were on track, 3 were almost on track, 12 were moderately off-track and 23 were seriously off-track. The overall conclusion is that only modest progress was made with the implementation of the NSSS after 4 years of adoption. There are substantial gaps that will require major efforts.

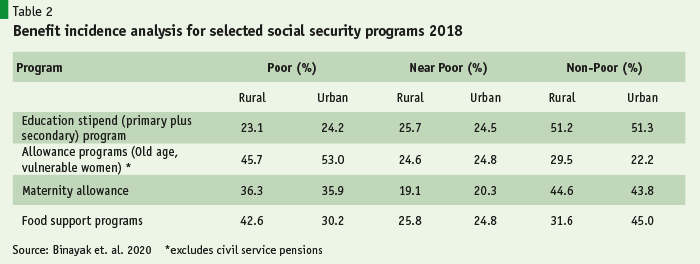

Most disappointing is the fact that there are still 114 specific active social security programs and not one single consolidated life cycle program had emerged as of June 2020. The absence of a consolidated online list of beneficiaries and the lack of a well-thought out beneficiary selection process are also major disappointments. Evaluation results of individual programs continue to show high exclusion and inclusion errors and continued leakages. In a recent study using data from Multiple Indicator Sample Survey (MICS) 2019, Binayak et. al. (2020) show that a substantial share of the benefits accrues to the non-poor. This prevails even when the target group is broadly defined to include the poor and the near-poor as suggested in the NSSS. The results are summarized in Table 2.

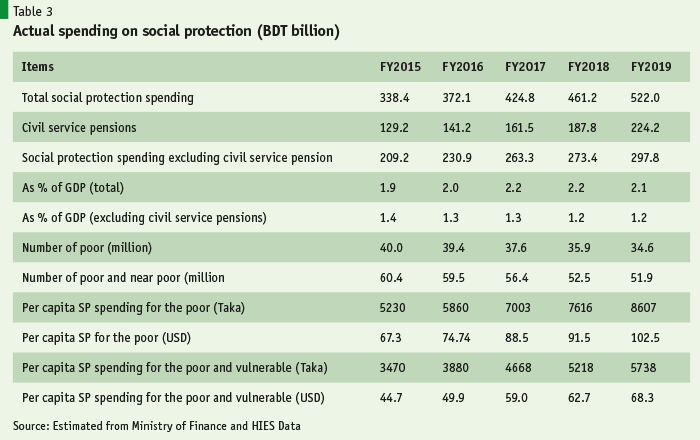

The area where the NSSS is facing the most difficulty is the availability of resources. The financing of social security programs has become a major challenge owing to substantial revenue shortfalls in the past 3 years. Contrary to expectations at the time the NSSS was formulated, budget resources have increasingly become constrained that has reduced the ability to provide higher allocations to most government programs including social protection. While the government budgets show large planned allocations, actual financing is substantially smaller. Also, much of the actual increase in social protection spending since FY2016 has happened for civil service pensions (Table 3). The large wage increases awarded to civil service employees in the FY2015-16 Budget has also translated in commensurate increases in civil service pensions. Excluding civil service pension, which accrues to only 0.6 million retirees and has very little poverty focus, total actual spending on social protection is around 1.2% of GDP. Also, it is falling as a percent of GDP.

Furthermore, there are questions regarding the inclusion of many programs funded from the development budget in the Ministry of Finance definition of social protection. These programs amounting to 0.2% of GDP concern spending in health, education, water supply and infrastructure; it is not obvious that these spending are targeted to the poor. Even so, and taking a very liberal approach to the definition of social protection spending as defined by the Ministry of Finance, total spending excluding civil service pensions (that have little or no poverty relevance) was Taka 298 billion in FY2019. This is very small for a country with an estimated 35 million poor and 52 million poor and vulnerable population. In per capita terms this amounts to an annual spending of a mere 8607 taka (102 dollars) per year when only the poor are included and taka 5738 (68 dollars) when the poor and vulnerable are included. Given the targeting errors, the actual benefits per poor person is considerably lower.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the Government’s response

The global COVID-19 pandemic has terrorized the world, unleashing huge number of infections and sad loss of lives. On March 23 the Bangladesh government imposed a lockdown that was extended to May 30, 2020. On the economic front many economic activities, especially in the urban areas, came to a grinding halt. Exports declined and many overseas workers have returned. GDP growth, tax revenues and export earnings all registered sharp reductions in FY2020. The government has taken a series of measures to reduce the spread of the infection and announced several stimulus packages to help the needy and stem the downward spiral of economic activities.

Government policy response

To mitigate the adverse impact of ‘global pandemic’ from COVID-19, the Government of Bangladesh has adopted a Work Plan with four major strategic programs to be implemented in immediate, short-term and medium-term span. The four major strategies the government has adopted are as follows:

a. Increased public expenditure with a target to create job. Funding of foreign tour and luxury expenditures from the government budget will be discouraged.

b. Introducing fiscal stimulus package to retain workers in the manufacturing sector, to maintain competitiveness of the enterprises especially in the export-oriented manufacturing sector and to revitalize the economic activities and business environment. The major policy interventions in this regard are to provide several credit facilities at low interest rate from the banking system for the businesses.

c. Expansion of social safety net programs to meet the basic needs of people living below poverty line, day labourers and for those who are engaged in the informal sector. The major interventions are: a) Free food distribution; b) sale of rice under Open Market Sale (OMS) program with a highly subsidized price (Taka 10 per kg); c) cash transfer to the targeted vulnerable population; d) expansion of allowance programs (Old Age Allowance and Allowance for Widow/husband Deserted Women) to all eligible person (100 percent) of the 100 most-poverty stricken Upazilas; and e) expedite construction of house for the homeless people.

d. Increase money supply to maintain liquidity of the economy so that the financial shock from the pandemic can be absorbed and day to day businesses can be operated smoothly. Bangladesh Bank has already lowered CRR (cash reserve ratio) and Repo rate to increase money supply and it will continue if needed. However, special attention will be given so that inflation does not increase as a result of increased money supply.

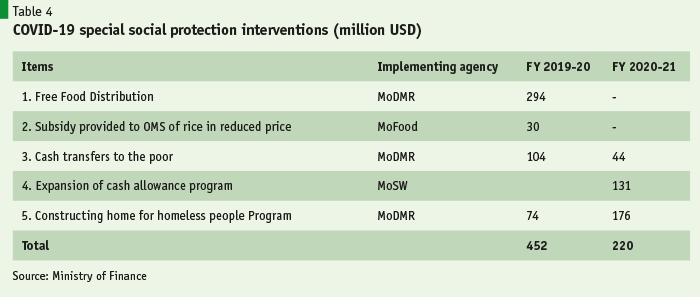

The COVID-19 stimulus package is broad-based. The value of the package is estimated at US$ 13.3 billion (4% of FY2020 GDP) and its fiscal cost is estimated at 2% of GDP. Much of the stimulus package was aimed at recovery of economic activities to support GDP growth, exports and employment. Direct social transfers to the poor and the vulnerable was very modest (Table 4).

Evaluation of the income transfer program

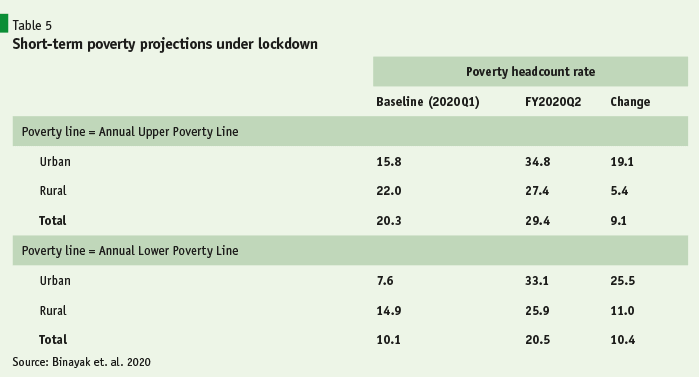

The stimulus package is undoubtedly comprehensive and seeks to provide a combination of measures to provide food and income support to the poor, improve health care, protect employment and revive economic activities. Preliminary estimates suggest that in the short-term in the absence of adequate income transfers national poverty rate might in 2020 Q2 might spike to 29%, up from 20% in 2020Q1 (pre-Covid-19 level), while extreme poverty might grow from 10% to 21%1. Research on what might constitute adequate income transfers suggest the need for some Taka 960 billion (3.8% of GDP) equivalent (Osmani 2020). As compared to this, the first-round income transfer in the government’s stimulus package amounts to a mere Taka 60 billion (0.2% of GDP). Additionally, newspaper reports suggest that the problem of targeting remains a major constraint to the effectiveness of the transfer programs. So, the overall conclusion is that the income transfer programs adopted so far, even if well implemented, are far lower than the massive amount of resources needed to prevent a surge in the incidence of short- term poverty.

Of course, income transfers are only one instrument and the stimulus package will likely have a good poverty reduction effect if income and employment opportunities grow for the poor. The stimulus packages relating to these opportunities include support to agriculture and micro and small enterprises (MSEs). Available evidence suggests that the rural economy has recovered fairly robustly, although the onset of serious flooding has caused problems for the poor. The revival of MSEs is less promising both because of the COVID-19 demand constraints as well as the huge MSE policy constraints that remain unaddressed (Ahmed 2020).

Social protection in the 8th Five Year Plan (8FYP): The way forward

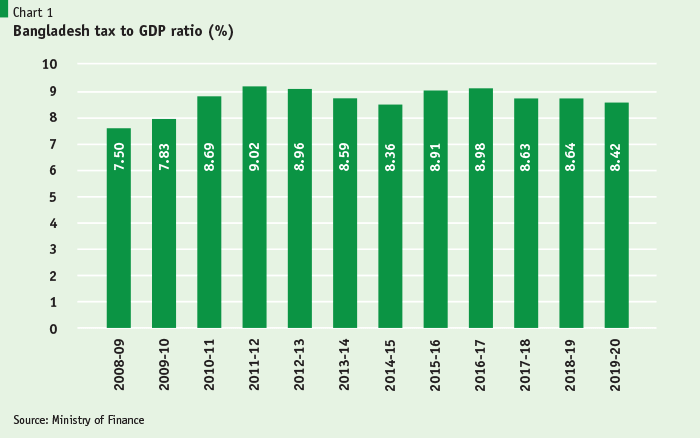

Even before COVID-19 happened, Bangladesh was going through a major revenue constraint owing to the weakness in revenue mobilization effort (Ahmed 2019). A manifestation of the revenue constraint is illustrated in Chart 1. Tax revenue as a share of GDP is one of the lowest in the world (Ahmed 2019). It is not only very low, it has been falling since FY2017, indicating the huge revenue mobilization challenge Bangladesh faces. The main consequence of this revenue constraint is the inability to allocate adequate resources to the core development programs including social security.

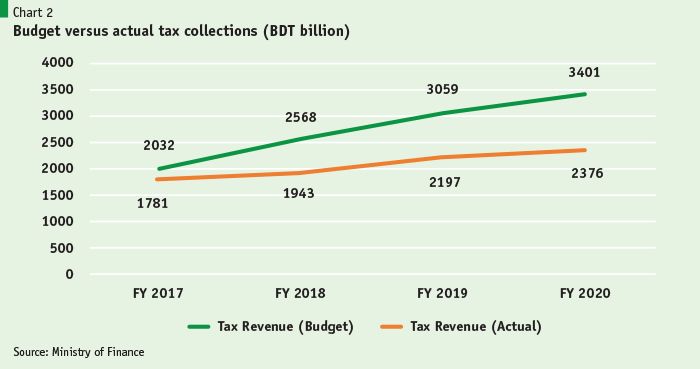

Another notable aspect of this revenue constraint is the expanding gap between budgeted and actual tax collections. This gap has become especially large in the past several years (Chart 2). For example, the revenue gap between budget and actual has grown progressively from 14% in FY2017 to whopping 39% in FY2019, which were pre-COVID periods. The gap has grown further in FY2020 to 42% owing to the additional losses from COVID-19 in the last 4 months of the Fiscal Year 2020. As a consequence, many budgeted expenditure items have faced ex-post budget cuts owing to revenue constraints. Most current expenditure items like civil service salaries and pensions, supplies and materials, defense, and interest payments are fixed obligations that cannot be cut. So, the main adjustment burden has been shared by the annual development program and the spending items in the nature of transfers (subsidies, grants to local government institutions and social security spending). The cuts have often been as large as 30% of the budget allocation.

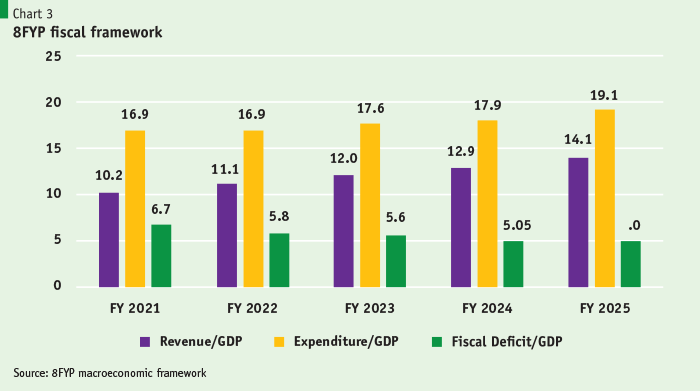

The Government is concerned about this falling tax to GDP ratio and the constraint it imposes on its development spending. To address the revenue constraint, the government prepared a medium-term fiscal framework (MTFF) for the Government’s Perspective Plan 2041 (PP2041) (Government of Bangladesh 2019). Related to the PP2041 MTFF, an MTFF has also been prepared for the 8th Five Year Plan (8FYP). The 8FYP MTFF builds in the adverse effects of the ongoing CIVID-19 pandemic but it also incorporates the government’s resolve to implement major tax reforms as envisaged in the PP2041 MTFF. The projected total revenue, expenditure and fiscal deficit paths for the 8FYP are shown in Chart 3. The fiscal deficits are consistent with sustainable external and domestic financing in terms of debt sustainability and monetary programing. Since these projected trends are predicated on the full implementation of revenue and expenditure reforms of the PP2041, actual outcome will be a function of these reforms and also the timing of exit of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shortfalls on either count will lower revenue and expenditure performance.

The 8FYP is the first 5-year program for the implementation of the PP2041, which has set a target for eliminating extreme poverty by FY2031. Among other policies, the ability to secure this target will depend upon the implementation of a well-thought out strategy for social protection. The 8FYP advocates stronger efforts to implement the NSSS, with emphasis on converting the large number of programs into the Life Cycle Framework provided in the NSSS, enhanced efforts to develop and put online a list of beneficiaries based on the income eligibility of 1.25 times the 2016-17 poverty line (NSSS definition of poor and near poor), converting all programs to cash basis, make all transfers online using G2P approach, sharply increasing the actual spending on social protection and doing real time results based M&E to monitor implementation.

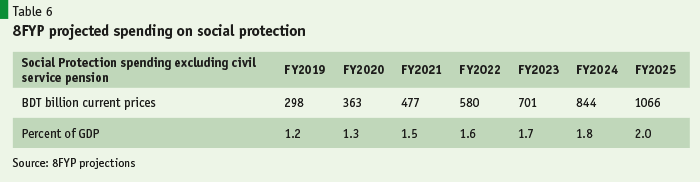

The implications of the fiscal policy framework illustrated in Chart 3 for resource availability for the social protection programs during the 8FYP is illustrated in Table 6. The planned target is to increase spending on non-civil service social protection from 1.2% of GDP in FY2019 to 2.0% of GDP by FY2025. This planned allocation is consistent with public spending priorities and available resource. This is a minimum level of social protection spending that will have to be ensured to support the poverty reduction targets of PP2041.

References

Ahmed, Sadiq. (2020). The Bangladesh Employment Challenge policy Brief. Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Ahmed, Sadiq. (2019). Fiscal Policy for an Upper Middle-Income Bangladesh, Paper presented to the 4th Bangladesh Economists Forum (BEF) Conference, Dhaka, November 2019.

Government of Bangladesh. (2019). Making Vision 2041 A Reality: Perspective Plan of Bangladesh 2021-2041. General Economics Division, Planning Commission, Dhaka.

Government of Bangladesh. (2018). Action Plan Implementation of the National Social Security Strategy (NSSS) of Bangladesh. Cabinet Division and the General Economics Division, Planning Commission, Dhaka, April 2018.

Government of Bangladesh. (2015). National Social Security Strategy (NSSS) of Bangladesh. General Economics Division, Planning Commission, Dhaka, July 2015

Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). (2019). Midterm Progress Review on Implementation of the National Social Security Strategy. Report prepared for the UNDP, Dhaka, May 2019.

Sen, Binayak, Zulfiqar Ali and Muntasir Murshed. (2020). Poverty in the Time of Corona: Trends, Drivers, Vulnerability and Strategic Policy Responses in Bangladesh. Background Paper prepared for the 8FYP, General Economics Division, Planning Commission, Dhaka May 21, 2020.

Osmani, Siddiqur Rahman. (2020). Coping with COVID: The Case of Bangladesh. The BRAC Institute for Governance and Development, Dhaka, May