Exchange rate matters for export performance

By

Development Context

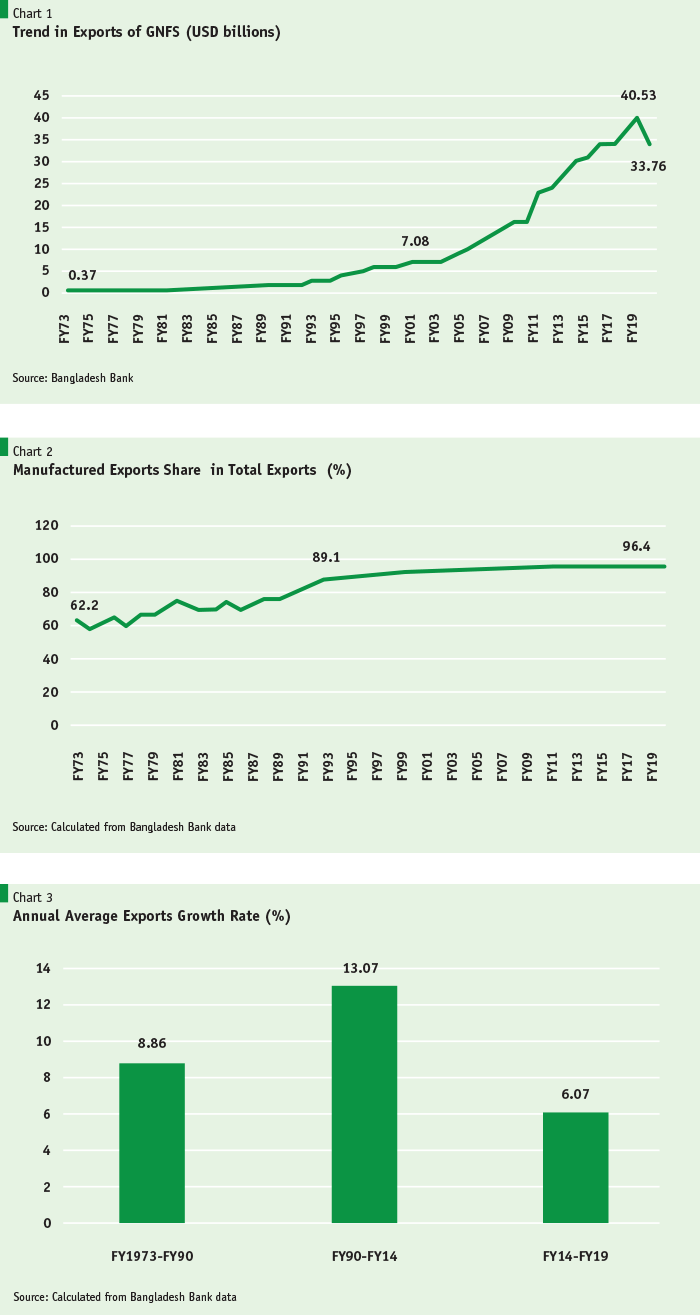

Bangladesh is an outstanding example of a low-income country that has successfully transformed its economy from a per capita income of below 100 USD in FY1973 to 2064 USD in FY2020. A major contributor to this performance is the rapid growth in exports, rising from below 0.4 billion USD in 1973 to 41 billion USD in FY2019 (Chart 1). What is of particular note is that this surge in exports came from the manufacturing sector rather than from a natural resource or primary product base (Chart 2). This amazing manufacturing sector performance is not a historical accident but under-pinned by good economic management.

Yet, this successful push for export growth has come under pressure for the past several years even prior to the on-set of COVID-19. Exports growth slowed down considerably since FY2014, growing at a pace of 6% per annum between FY2014-FY2019 as compared with 13% per year between FY1990-FY2014 (Chart 3). The onset of COVID 19 in March 2020 devastated the export sector most severely as export earnings plummeted by 17%, falling from 41 billion USD in FY2019 to only 34 billion USD in FY2020 (See Chart 1). While recovery is underway in FY2021, export earnings will at best recover to around 40 billion USD but likely will fall short. Even if it recovers to 40 billion USD, export growth would average a mere 4.2% per year over the periods FY2014-FY2021, which amounts to a substantial downturn in exports performance and is a far cry from the solid performance of 13% plus growth registered over the 24 years between FY1990-FY2014.

The recovery of exports to around the FY1990-FY2014 path characterized by double digit growth in export earnings in nominal dollar terms is of paramount importance to enable Bangladesh attain its aspiration to reach upper middle-income country (UMIC) status by FY2031, restore the momentum of job creation, and to eliminate the incidence of extreme poverty. While the COVID-19 induced fall in export earnings is an understandable consequence of a major external shock, it is important for Bangladesh to prepare and implement a rapid export recovery strategy based on a good diagnostic of the determinants of export performance and underlying constraints and identifying policies that will remove the constraints to restore export performance to the FY1990-FY2014 path.

The recovery of exports to around the FY1990-FY2014 path characterized by double digit growth in export earnings in nominal dollar terms is of paramount importance to enable Bangladesh attain its aspiration to reach upper middle-income country (UMIC) status by FY2031, restore the momentum of job creation, and to eliminate the incidence of extreme poverty.

Determinants of Bangladesh Export Performance

Research suggests that Bangladesh export performance during the upswing benefitted from several policy and international enabling factors. On the policy front, Bangladesh exports benefited from a sound macroeconomic policy framework that kept inflation and interest rates low, good access to low-cost bank credit, a flexible and competitive exchange rate, dismantling of trade and investment barriers, especially the removal of quantitative trade barriers and the cut back in import duties, strong policy support to the leading export activity – readymade garments (RMG), and improvement in infrastructure, especially power supply. The RMG sector led the charge in export performance, taking advantage of low-cost labor and partnership with the Korean firm Daewoo that brought in technology and FDI in the RMG sector. The initial spurt was provided further impetus by a number of major policy support from the government including the access of RMG to duty-free imports of intermediate goods through a system of bonded warehouses (BWS), back-to-back line of credit that allowed RMG exporters to finance imports from export earnings, and special fiscal incentives. The international environment was also supportive of RMG exports through the phasing away of the Multifiber Agreement that eliminated quota restrictions on RMG export volumes and through duty-free access to European markets based on Bangladesh’s LDC status.

Because of these positive factors, exports of RMG boomed. But other exports did not prosper similarly. Some showed signs of energy benefitting from the initial overall positive environment for exports but soon faltered as the policy environment for exports weakened. Two primary reasons for the differential supply response between RMG and non-RMG exports are firstly, the initial conditions that boosted RMG investment and exports, and secondly, many of the policy support to RMG, especially the access to duty free imports of intermediate inputs through the BWS, were not available to other exporters.

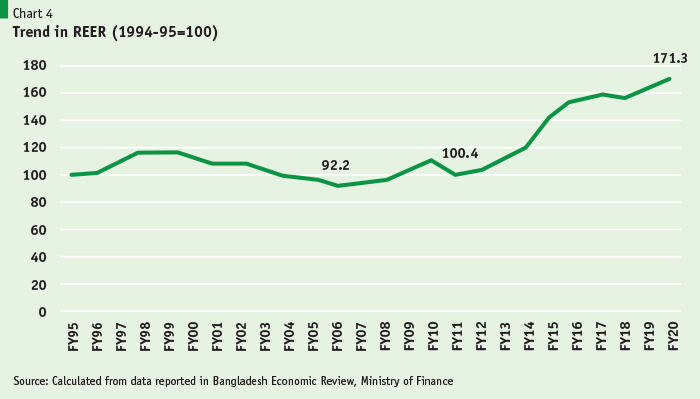

Research shows that a number of constraints have started dominating the export environment. Trade reforms have faltered while a range of complex and unpredictable supplementary and regulatory duties on imports took over to largely offset the reduction in custom duties. The high rates of duties for consumer goods relative to intermediates and capital goods also meant that the effective rate of protection (ERPs) for these products are substantially larger than for intermediate and capital goods. Investors soon discovered that it is lot more profitable to produce for the domestic market based on high ERPs for consumer goods than invest in exports. Moreover, the exchange rate management since FY2006 has turned against exports. The appreciation of the real effective exchange rate (REER) has been particularly sharp after FY2011, appreciating by 71% between FY2011-FY2020 (Chart 4). This is a huge tax on exports and serves as a double penalty on top of the large ERPs for domestically produced consumer goods.

The high rates of duties for consumer goods relative to intermediates and capital goods also meant that the effective rate of protection (ERPs) for these products are substantially larger than for intermediate and capital goods. Investors soon discovered that it is lot more profitable to produce for the domestic market based on high ERPs for consumer goods than invest in exports.

It is hardly surprising that non-RMG exports have failed to take off in this policy environment of huge anti-export bias. The government has tried to offset these disincentive effects of trade policy and exchange rate on exports through export subsidies and tax breaks. But these interventions are much smaller in size relative to the disincentive effects to make any material difference. RMG exporters are also unhappy. While they have succeeded in extracting special fiscal incentives, including export subsidies, concessional credit and large tax breaks, they complain that profit margins are sharply down owing to the large appreciation of the REER. Additionally, the fiscal cost of these incentives is substantial in an environment of severe fiscal resource constraint.

Real Exchange Rate and Exports

Economic literature is unambiguous that a long-term REER appreciation is bad for exports. Many development economists even argue for an under-valued REER to support export-led growth at the early stages of development (low to middle income countries). China’s example is the most well-known case for this. The policy challenge, however, is the feasibility of implementing such a policy. In the case of Bangladesh, the government did a commendable job in the early phase of the export boom by depreciating the currency and keeping REER stable with a slight depreciating trend (Chart 4). However, this policy could not be sustained. REER appreciation was initially caused by excessively expansive monetary policy over the FY2009-FY2012 periods that saw a sharp rise in inflation and pressure on the balance of payments. Corrective measures were quickly taken including the depreciation of the Taka and a reduction in monetary growth rate. However, following an initial correction, the REER appreciation path has continued owing to the heavy influx of remittance earnings and acceleration in GDP growth. Since the balance of payments is either in surplus or in mild deficit, there is a perception that the REER appreciation is market determined and therefore an equilibrium phenomenon. The policy challenge is seen as one of ensuring that the volatility of the exchange rate is minimized without worrying about the upward trend.

Policy makers worry that any policy correction to offset the appreciation through adjustments in the nominal exchange rate will induce inflation by raising the domestic price of imports. Critics of policy-induced nominal exchange rate depreciation also argue that that real exchange rate is only one determinant of exports. The adverse effects of REER appreciation on exports can be offset through other policy interventions like improvement in labor productivity through investment in skills and technology, penetrating in new markets by participating in global value chain (GVC), facilitating FDI in exports, improving infrastructure, and reducing trade logistic costs.

Global experience does show the importance of these other determinants of export performance. A good example is Vietnam that has benefitted substantially from FDI, investments in technology, investments in labor skills, export of intermediates through participation in GVC, and expansion of export markets through free trade agreements. However, these advantages did not happen accidentally. They required major policy interventions including massive trade and investment deregulation that sharply lowered trade protection, opening up FDI in all domestic markets though progress in many areas of cost of doing business, and spurring the growth of technology exports through investments in higher education and R&D. Sharp reduction in import duties also allowed the growth of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Foreign investors have found the cost of doing business in Vietnam as sharply declining based on reforms.

None of the above factors are true of Bangladesh. Total FDI inflows have languished at around 2.0 billion USD annual inflow due to the high cost of doing business, technology exports are virtually non-existent, Bangladesh does not participate in GVC and is not a member of any consequential FTA. Importantly, Vietnam sharply reduced trade protection and maintained prudent macroeconomic management with low inflation and a stable exchange rate. Vietnam also did not lose track of the REER that shows some mild appreciation but not anything in the magnitude experienced in Bangladesh over the past 9 years.

Using the present environment of current account surpluses as an indicator of equilibrium in the exchange market is misleading for several reasons. First, it is predicated on continued rapid inflows of remittances that are by no means guaranteed. Remittances could well disappear as per capita income grows in Bangladesh and demand for domestic labor expands. Second, the favorable outcome in the current account is sustained not only through trade protection that lowers import demand but also through huge restrictions on services account. Exchange controls are rampant in Bangladesh with many restrictions on services imports, Bangladeshi investments abroad, foreign exchange surrender requirements etc. These exchange controls are not consistent with the emergence of a dynamic economy that needs to be much more open to FDI and that seeks to attain UMIC Status within the next 10 years. As the services account is further liberalized, demand for foreign exchange will go up and the current account surplus will vanish.

The Way Forward

In the present policy environment of Bangladesh, the most practical and easy way to reinvigorate exports is to lower trade protection and reverse the sharp appreciation of the REER. These policy reforms can be done literally by the stroke of a pen and the results in terms of export response will be fairly rapid. Progress in other areas noted above are absolutely important but, they will take several years of sustained efforts before results in terms of an export surge will be possible. Importantly, the sharp appreciation of the REER at this stage of Bangladesh development is hurtful of exports, employment and overall growth prospects and must be corrected.

As noted, the adjustment of the nominal exchange rate downward to compensate for the REER overvaluation is resisted by policy makers on the ground that this would stoke inflation. One possible way to compensate for that is to combine this policy with a reduction in trade protection. The two policies will not only reinforce each other in terms of improving the incentives for exports, the inflationary effects of nominal exchange rate depreciation can be avoided. Reduction in trade protection will boost imports that will support private investment and GDP growth and also help contain the appreciating influence of remittance inflows on REER.

Finally, an important way that the REER appreciation can be avoided while maintaining a stable nominal rate is to lower inflation in Bangladesh. Since FY2012, Bangladesh has already achieved considerable success in reducing inflation through prudent monetary and fiscal policies. This is a major policy victory for Bangladesh. While celebrating this achievement, there is scope for further reduction in inflation through monetary tightening. At around 6%, the Bangladeshi average inflation rate is still too high compared to the inflation rate in the major trading countries, especially USA, EEC Countries, China and Japan.