Why Bangladesh urgently needs a coherent National Tariff Policy

By

The rise and fall of tariffs

When it comes to tariffs, by and large, all trade economists agree on one thing, that tariffs are among the most lethal instruments of trade restriction. History of the development of global trade confirms that proposition. In recent history, the most ruinous application of tariffs happened at the onset of the Great Depression when the United States congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, raising tariffs across 20,000 imported commodities thus quadrupling average tariffs to 19.8%. Notably, this was not a measure to mobilise revenues but to protect domestic industries by restricting competing imports. Tit-for-tat tariffs by America’s trading partners followed, with catastrophic global consequences – reduction of world trade by roughly 50%, against 67% reduction of US trade (imports and exports). US GDP was down 50% at the close of the Great Depression, partly due to the adverse impact of tariffs, with similar impacts on economies around the globe. Economists agree that the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs exacerbated the Great Depression and led to a collapse of world trade resulting in lower national incomes and higher poverty.

Following the close of WWII, leading economists and world leaders assembled in Brettonwoods, New Hampshire, and urgently got down to the task of rebuilding the global trade architecture. The highest priority was the dismantling of high tariffs (unilaterally for the USA) as the principal means to restore global trade flows. The institution that emerged as the great saviour was the General Agreement for Tariffs and Trade (GATT), followed by its successor, the WTO (in 1995). Credit goes to these two global institutions in effectively dismantling tariffs around the world which helped to stimulate trade and, in its wake, income growth. Global average tariffs are now at their historic lows, roughly around 6%. There is general consensus among trade economists, based on decades of research, that lower tariffs stimulate trade and growth (Irwin, 2019). The general impression at the multilateral level is that the tariff problem of trade is all but resolved. But is it? The record shows that in times of crisis, like the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-09 and the COVID-19 pandemic of today, protectionist tendencies that include tariff raising re-emerge, in various degrees, and impede global trade.

A somewhat different path in the evolution of tariffs appeared on the horizon of developing economies. With countries coming out of colonial rule after the second World War, all aiming to grow out of poverty at a rapid rate, the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis (PSH) seemed to offer the path to industrialization and growth. The PSH dogma argued for, among other measures, raising tariffs to protect and promote import substituting industries. Consequently, tariff protection to “infant” industries was widely accepted as the norm for much of the developing world in the 1960s and 1970s, until the emergence of an alternative paradigm – export-led industrialization and growth – revealed that all was not well with the P-S approach to development. Make no mistake, the ghost of protectionism is still alive and well to this day.

Though much diminished globally as a trade barrier, tariffs are lethal in their impact on trade as the recent US-China trade tensions have shown. Bangladesh, now a dynamic export-oriented economy, is still encumbered with import tariffs to generate revenue as well as provide protection to domestic industries. But unusually high and dispersed tariff structure serves as a barrier to further beneficial trade integration with the world market besides creating inherent disincentives to export performance as well as its diversification. Addressing this distinctive challenge in Bangladesh’s trading landscape has become a national imperative and a driving force in the search for a tariff policy that supports our long-term strategy of export-oriented development. PRI research has revealed that the current tariff structure and trends run counter to that national objective. Hence, the urgent need for the formulation of a coherent national tariff policy.

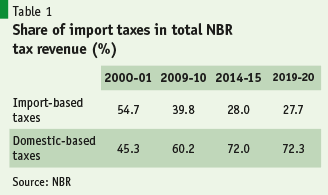

Tariffs generate revenue and protect industries. Mobilization of revenue without distorting business incentives continues to be a major challenge for the Government. Though a strategic shift from import to domestic-based revenue sources is taking place (Table 1), the Government’s continued heavy reliance on import-based taxes for revenue collection pose quite a few challenges. The existing structure and distribution of customs tariffs present a number of anomalies that create problems for customs administration, on the one hand, and distort business incentives, on the other. Simplicity and transparency – two critical yardsticks for judging the efficiency of tariff administration – are often sacrificed in the interest of raising revenue or providing protection to domestic activities.

The efficiency with which import taxes are collected has a direct bearing on overall revenue mobilization and trade facilitation; the latter objective figuring more prominently in the policy space as the economy becomes more integrated with the world economy through trade. Finally, how efficiently and effectively NBR collects import taxes affects incentives in business and investment, and, in consequence, on the dynamism of the manufacturing sector, competitiveness of our exports, and overall economic performance.

Presently, tariffs and para-tariffs are used as the main instruments of protection. Para-tariffs are defined as all import taxes, other than custom duties, having a protective effect. Supplementary Duties (SD) and Regulatory Duties (RD) are the main para-tariffs in the Bangladesh tariff regime. Supplementary Duties (SD) were first applied on imports in 1991 under the VAT and Supplementary Duty Act of 1991, as a trade neutral tax (i.e. applied equally on imports and domestic import substitutes with no protective effect) with the express objective of protecting revenue from the previously high taxation on so-called “luxury goods”. In course of time, however, the trade neutral aspect of SD appears to have been abandoned by reducing or eliminating the domestic part of the tax, while leaving the import component in tact with the result that, for all practical purposes, SD, by and large, became a protective tax. In addition, another para-tariff, Regulatory Duty (RD), was added on an annual imposition basis but seems to have earned a permanent character. For NBR, SD and RD are ostensibly revenue instruments and, for the most part, imposed on tariff lines that are already subject to the top 25% rate of CD.

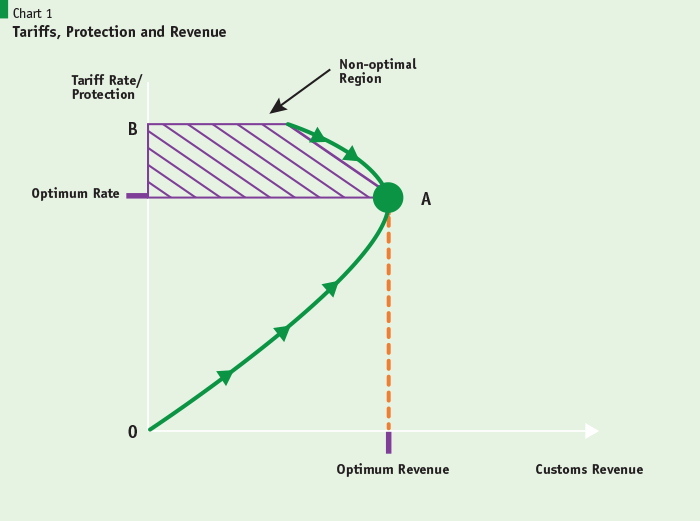

But the protective effects of SD and RD cannot be ignored. The notable point is that tariffs and para-tariffs serve protection and revenue objectives (dualism) which may be in conflict with each other (Chart 1). The chart illustrates the potential dilemma for policymakers.

The main point is that higher tariff rates may yield higher protection for domestic enterprises, but revenue outcome is another matter, as demonstrated by the curve OAB. Customs revenue is the outcome of imposition of duties and taxes on imports. Revenue may rise with higher tariff rates, but up to the point A, which is the point indicating optimum revenue at an optimum tariff rate. Tariff rates above this point will raise protection higher but will be so restrictive on competing imports as to act as de facto bans resulting in lower imports and lower revenue yield. The challenge for policymakers is to find out where the level of the current tariff rates lies. If it is above the optimum rate, then the shaded area shows that a reduction in the tariff rate may actually generate higher revenues, but protection will be lower, which means there will be resistance from import substituting enterprises producing for the domestic market. How do we know whether current tariff rates and protection levels are above or below the optimum level? One way to find out is by using simulation models that can generate revenue outcomes of hypothetical reduction or increase in tariff rates. If hypothetical reduction in tariff rates and protection levels yield higher customs revenue, then that indicates current tariff and protection levels are in the non-optimal region. In that case, from the revenue point of view, Bangladesh tariffs are higher than what is necessary for maximizing revenue. The critical question before policymakers, as they consider tariff rationalization, is whether existing tariff rates are above or below the “optimal rate”.

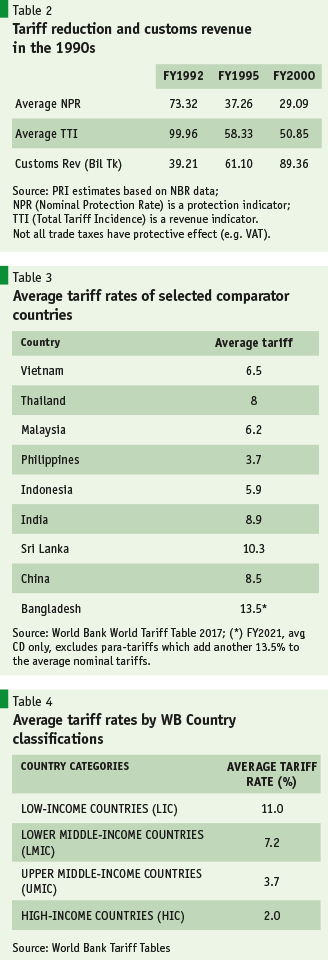

The Bangladesh experience during the intensive trade reform period of FY1992 through FY2000 is instructive (Table 2). As average NPR/TTI dropped from 73%/99% in FY1992, to 37%/58% in FY1995, and 29%/51% in FY2000, customs revenue was up 56% by FY1992 and 127% by FY2000, growing at an average rate of 16% during FY92-95 and 11% for the entire decade. The sharp decline would have turned heads in the NBR and Ministry of Finance, but that never happened as revenue growth was prolific: proof that tariff rates were significantly higher than the optimal rate.

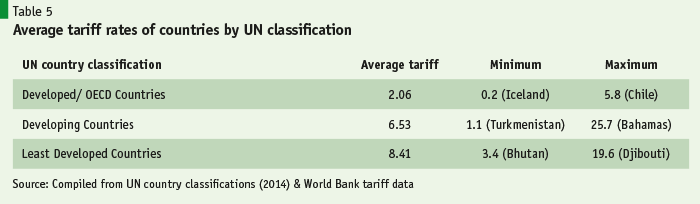

Another way of looking at whether Bangladesh tariffs are relatively high is to compare them with tariffs in economies at similar level of development or national income. Table 3 posits Bangladesh tariffs with selected comparator economies, while Tables 4-5 puts them in the context of country income classifications of World Bank and UN system. All comparisons indicate Bangladesh average tariffs are above the fray, even above average tariffs of LICs.

Bangladesh tariff and protection trends

It is important to acknowledge that the 1990s decade saw radical changes in trade and tariff policy. Trade liberalization with tariff reduction and rationalization was adopted as a signal of the radical change of direction from past policies. By the close of the 1990s, Bangladesh economy was included among a select group of developing economies described as “globalizers” by the World Bank. A 2001 World Bank study of developing countries (Dollar and Kraay, 2001) found that, unlike non-globalizers, countries that were “globalizers” experienced growth acceleration as well as poverty reduction in the 1990s. This was also Bangladesh’s experience starting from the 1990s decade. After unsuccessfully targeting 5% GDP growth for the first two decades post-independence, for the first time GDP growth in the 1990s averaged 5% for the decade while export growth for the first time crossed double digits averaging 12%. Particularly, the period of 1996-2001 experienced a robust growth in export led growth of Bangladesh economy due to trade liberalization.

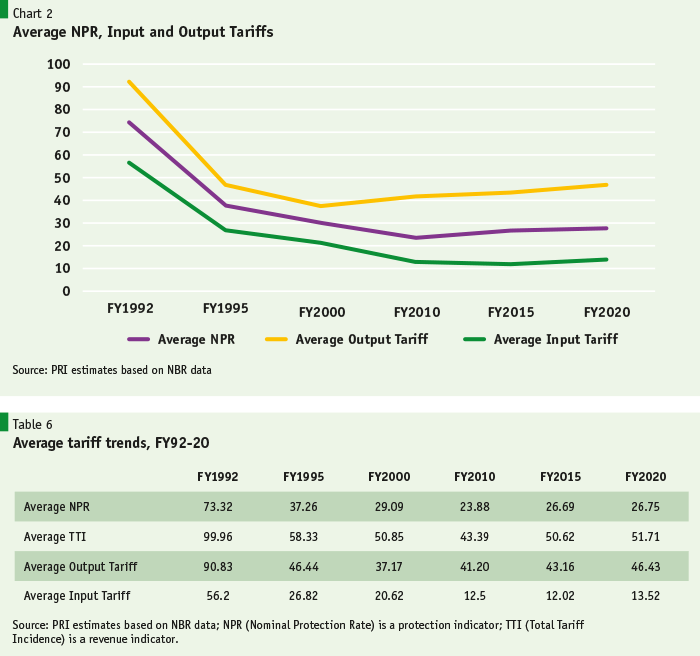

Thanks to the change in direction of Bangladesh’s trade orientation in the 1990s decade, there has been progress in rationalization of the tariff structure towards making it more export friendly. But reforms started in the 1990s slowed down over the following decades leaving the structure of tariffs antiquated when compared to that of comparator economies. A review of tariff trends and movement in output and input tariffs reveals the crux of the problem (see Chart 2 and Table 6 below).

The tariff trends reveal some striking features that are relevant for policymakers to take note. Though average tariffs trended downward between FY1992 and FY2020, the sharp reduction in average NPR (a measure of nominal protection) over the 1990s decade appears to have tapered off during the subsequent two decades. The sharpest reduction in tariffs occurred during 1992-2000. A close examination will reveal that much of the reduction in average NPR in the past 20 years was due to reduction in average input tariffs which declined to 13.5% in FY20 from 20.6% in FY2000, while average output tariffs rose from 37% to 46.6%. This is a clear indication that effective protection levels, already high by international standards, have increased and was confirmed by a recent PRI-IFC study (Sattar, 2020). What is problematic is that tariff protection and export performance are not mutually exclusive events. PRI research has revealed that, in the Bangladesh context, such high protection seriously undermines export performance and its diversification (Sattar, 2012).

The sharpest reduction in tariffs occurred during 1992-2000. A close examination will reveal that much of the reduction in average NPR in the past 20 years was due to reduction in average input tariffs which declined to 13.5% in FY20 from 20.6% in FY2000, while average output tariffs rose from 37% to 46.6%.

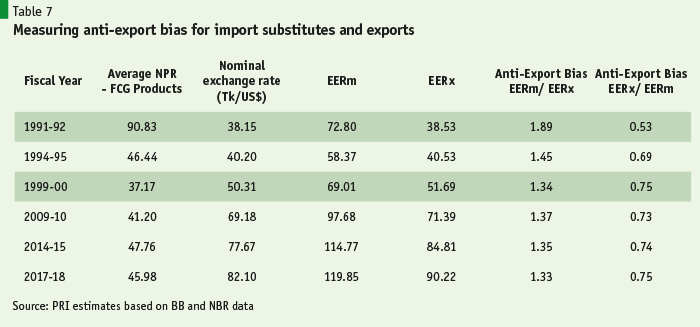

Tariffs, exchange rate, anti-export bias

Trade economists recognize the adverse impact of tariffs on the exchange rate. With import demand being curtailed under high protection, import-related (ex-ante) demand for foreign exchange is being curtailed, thus enabling the exchange rate (i.e., a lower domestic currency price for USD) to be lower than otherwise (implied appreciation/over-valuation). This would mean that export proceeds, expressed in domestic currency, would be lower than what the exporter would receive had the protection levels provided by import duties and other instruments been lower. This is an indication of the anti-export bias which can be measured by the relative returns from a dollar of foreign exchange earned by exports versus a dollar of foreign exchange saved by import substitute production (Table 7). The relative returns measured in terms of effective exchange rates for imports versus exports (EERm and EERx) show higher returns from import substitutes than exports for the entire period FY1991-92 through FY2017-18 – indicating persistent anti-export bias — though tariff reductions over that period did bring down the degree of anti-export bias, declining sharply at first from 89% in FY92 to 45% by FY95, then hovering around 33-37% ever since until FY2017-18. This is a disturbing sign that anti-export bias of tariff policy has been stubbornly persisting for decades. That clearly saps the incentives for Non-RMG products to seek the export route. Trade economists have long argued that for exports to be incentivised it is critical that there be no anti-export bias, even pointing to the need for a favourable treatment of exports. RMG exports are not subject to this anti-export bias as they operate in a “free trade” enclave of zero tariffs for imports (inputs) and exports.

Research shows that high tariff protection is the main source of anti-export bias. Export success so far has been limited to readymade garments (RMG) without much traction in other labour-intensive exports. Among other things, there is an inherent conflict between export policy and protection policy, which are not mutually exclusive. This needs to be recognized and actions need to be taken to streamline these policies. High tariffs raise the relative profitability of domestic sales compared to exports, thus discouraging production for exports. Thus, there is an inherent bias of incentives skewed in favour of import substitute production rather than exports. This has to change.

Research shows that high tariff protection is the main source of anti-export bias. Export success so far has been limited to readymade garments (RMG) without much traction in other labour-intensive exports. Among other things, there is an inherent conflict between export policy and protection policy, which are not mutually exclusive.

Policy priorities in the 8th FYP and WTO compliance

Having established that the two inter-linked policy of rationalizing the protection structure and sufficiently incentivizing exports needs immediate attention, the Government has now endorsed a combination of these two policies in the 8th FYP as critical components of its strategy of export-led development and inclusive growth – also an agenda of the SDG 2030. Since protection levels are high, any support to export (e.g., subsidies) will have to be high, but such measures will be fiscally unsustainable and will also fall afoul of WTO rules. More complaints will be forthcoming from competitors following LDC graduation. The imperative of being WTO compliant in our trade practices will be all the more pressing upon graduation from LDC status in 2026. So, there is no option but to rationalize the level and structure of protection to import substitute industries in order, on the one hand, to minimize the level of anti-export bias and, on the other, to move towards WTO compliance.

As Bangladesh graduates out of its LDC status, it will need to be cognizant of some WTO rules that it had hitherto ignored – particularly, those relating to levels of protective tariffs and prevalence of para-tariffs. The WTO recognizes CDs as tariffs while RD and SD fall in the category of other duties and charges (ODCs) in the WTO nomenclature and would have to be included with CDs once Bangladesh graduates out of LDC status. Though RD was flagged in the 2019 Bangladesh Trade Policy Review, SD with all its protective features appeared to be outside the WTO radar. That could change upon graduation. Besides making the tariff structure WTO compliant SD reform (moving toward trade neutrality consistent with the new VAT Law of 2012) would be essential for eliminating anti-export bias.

Other multilateral disciplines will also come into play, such as rules governing intellectual property, subsidies, standards, and trade-related investment, which are going to be the same for developing and developed economies. Moreover, if Bangladesh were to seek membership of regional trading blocs, like RCEP, it would have to submit to their disciplines which are also likely to be stringent. Broadly speaking, economic institutions in Bangladesh will have to start getting ready to face and conform to a more competitive and rules-based global trading environment in the future. Nevertheless, trade facilitation with improved customs infrastructure and administration will remain effective mechanisms to promote exports while being consistent with multilateral rules.

Bangladesh is a significant beneficiary of the multilateral regime symbolized by WTO, possibly with forthcoming reforms. As such, it would be strategic for Bangladesh’s tariff structure to gradually be made fully compliant with WTO rules, particularly as the economy moves towards graduation out of LDC status by 2026.

Streamlining trade and tariff policies calls for a five-year program of adjustment culminating in a trade and tariff regime that is reflective of or trending towards a UMIC economy, a goal that is set for 2031 in the Bangladesh Perspective Plan 2021-41. Needless to say, the current tariff regime, which is replete with para-tariffs for protection purposes and the near absence of tariff bindings on manufacturing products, will have to change after LDC graduation. Both external (opening markets by seizing opportunities of bilateral, regional and plurilateral agreements) and domestic content (eliminating anti-export bias by balancing incentives for exports and domestic sales) of trade policy will have to be revamped to fit the demands of a dynamic global market and an export-oriented trading regime, not to mention the impending structural adjustments that might be unleashed into the manufacturing and service sector by the ongoing 4IR.

Streamlining trade and tariff policies calls for a five-year program of adjustment culminating in a trade and tariff regime that is reflective of or trending towards a UMIC economy

But progress at global integration has been slow as tariffs remain stubbornly high and complex. With LDC graduation looming large we can ill afford to remain complacent. Unless trade policy reforms are taken to the next phase (i.e. rationalizing tariff structure and trends) LDC graduation in 2026 could serve as an adverse shock to the economy. The task is cut out for speedy action on the tariff front.

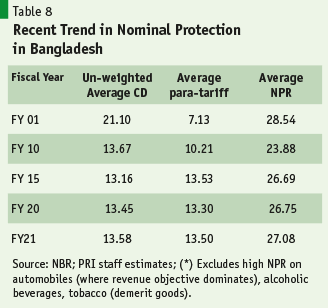

Current Structure of Nominal Tariffs. Analysing the relative incentives for exports and domestic sales requires analysis of nominal and effective protection on various categories of products imported under the tariff and import tax regime. Tariffs and QRs together determined the extent of openness or restrictiveness of trade policy in the 1990s and before this period. The QR slate has been almost wiped clean since FY2005, with tariffication of the remaining QRs. Tariffs on imports are now the main instrument of trade policy and protection. The tariff structure has been simplified by moving to only five non-zero tariff slabs – 1%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 25%, from 22 slabs in 1991. Although the average CD has come down over the past 19 years, the average nominal protection rate (NPR) shows mixed trend (Table 8). It initially declined between FY01 and FY10 and then started rising again over FY10-FY19.

Work is needed on three key aspects of the tariff structure and its trend:

- proliferation of para-tariffs, for protection

- a growing wedge between output and input tariffs

- tendency for perpetual protection, without a timeline

The Proliferation of Para-Tariffs

Only CD is recognized as tariffs for cross-country comparison. Other trade taxes like may be described as para-tariffs which are ad hoc instruments of trade and tariff policy affecting relative incentives between production for exports and domestic sales. These para-tariffs comprise mainly of two trade taxes: a regulatory duty (RD) and a range of supplementary duties (SD).

Regulatory Duty (RD): The Customs Act 1969 contains provision of imposing RD every year with the budget but requires yearly renewal. The RD rate for FY2012/13 was a rate of 3% applied almost uniformly on all products subject to the top rate of 25%, thus making the effective top CD rate to be at least 30%, when SD is applied. For all practical purposes, RD is an additional CD applied on all goods subject to the highest CD rate of 25%. In FY2021, the predominant RD rate is 3% applied to 45% of tariff lines. In the past few years, multiple rates of RD started emerging (5, 10, 15, 20, 35) though limited to under 100 tariff lines so far.

Supplementary Duty (SD): SD has become an expedient instrument of protection through its differential application (higher rates on imports; lower or zero rates applied to import substitutes or domestic production) with exemptions issued through SROs. PRI research (Sattar, et al, 2017) shows that 95% of SD is applied for protection purposes. So far, such rampant use of para-tariffs seems to have escaped attention of WTO Trade Policy Review, since cross-country tariff comparisons available in UNCTAD’s COMTRADE database do not have information on para-tariffs. These para-tariffs are regarded as Other Duties and Charges (ODCs) by the WTO and could become irritants in a post-LDC scenario.

Growing wedge between output and input tariffs. A closer examination of the structure of tariffs reveals that the decline in average NPR was due primarily to the reduction in tariffs on basic raw materials, capital goods and intermediate inputs, while the top CD rate remained flat at 25% since FY05, topped up by generous supplement of levies (RDs and SDs)– para-tariffs. The proliferation of para-tariffs has indeed been a major negative feature of the trade policy regime in Bangladesh contributing about 50% to the value of the average NPR in FY2021 (Table 8).

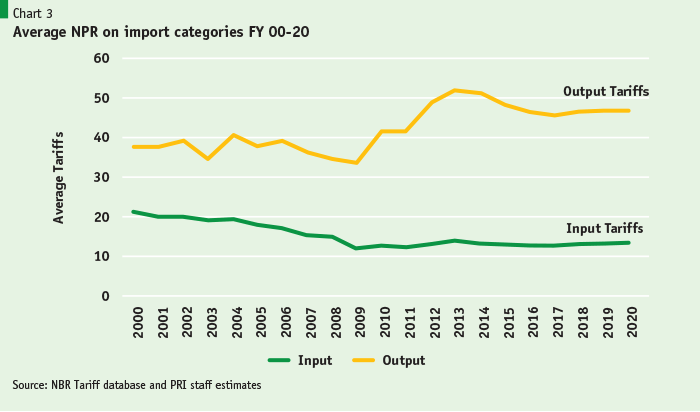

Chart 3 shows that in the recent past the average NPR for input categories (input tariffs) have been declining rapidly while that of final consumer goods (output tariffs) remained practically flat. This trend could be symptomatic of the priority demand for higher revenue. The fact that there is hardly any objection from the producer community against the application of higher rates on final consumer goods while depressing rates on imported inputs used in the production process testifies to their favorable impact on tariff trends and thus higher effective protection. Also notable are the prohibitively high NPRs on consumer goods that are domestically produced. Such high rates, if effective, constitute de facto import bans (e.g. biscuits enjoy 113% NPR in FY2020).

Tariff Strategy for Geriatric Infants in the industrial sector. “Infant industries” is a jargon used in trade economics for new firms and industries in the international marketplace. Two questions are immediately relevant in the Bangladesh context: (a) how long was an industry to be considered an infant industry, and (b) how much or how high protection is needed to be adequate. In the absence of clear theoretical or empirical guidance on these two counts, protection to Bangladesh industries has been high and for an indefinite period.

The practice of ad infinitum protection to industries cannot be taken as policy support to infant industries because so many of the protected industries have been in business for decades. Promising industries like agro-food processing, footwear and leather products, electrical gadgets, plastics, and ceramics have export potential but high tariff protection for decades makes domestic sales more lucrative, discouraging exportation. When we talk of export diversification, the focus is on these industries, in addition to jute goods, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and light engineering products. But emerging industries established in recent years, like bicycles, motorcycles, mobile phones, air conditioners and refrigerators, would indeed fall in the category of infant industries, to be supported with tariffs and other incentive measures available with the Government. But simple logic (bolstered by trade theory and policy) suggests that such support measures must be made time-bound or performance-based to be effective in developing efficient and competitive industries. This was how some of the successful developing economies in East Asia managed their industrial development. Eventually, they were able to pare down protective tariffs and compete in the global marketplace. That is a good practice to follow.

The practice of perpetual protection, rather than building robust competitive industries of the future, could become a path to nowhere, besides creating and sustaining a whole bunch of industries that are likely to need life support indefinitely. If industries require high protective tariffs, after being in business for 20, 30, or 40 years, they cannot be regarded as infant industries but could be termed as ‘geriatric’ infants. Unfortunately, the list of geriatric infants in our industrial sector is large and only getting larger. Rapid scaling down of protection for such industries is in the national interest, in the long-term interests of the industries concerned, and would be of immense benefit to the average consumer in Bangladesh.

Future protection approaches must include time-limits and performance criteria. The only way to ensure they become competitive over time is by gradually reducing protective tariffs and increasing import competition. The anti-export bias will also decline as protection is reduced. One approach to do this without major disruptions in manufacturing output or employment is to announce staggered reduction of protective tariffs in every forthcoming annual Budget – in greater degree for geriatric infant industries and much slowly for the promising infant industries of today.

Consumers need relief from the burden of the Protection Tax. Through tariffs on imports, and consumption taxes (e.g. value added tax or VAT) on local sales, prices paid by consumers are higher than what they would be in the absence of such taxes. Producers and their firms may be the first in line to pay tariffs on imports and taxes on local sales. But at the end of the day, it is consumers that bear the burden of these tax instruments as producers pass on the tax burden to consumers in the form of higher tax-induced prices including mark up. Consumers suffer welfare loss from protective tariffs on three counts, due to:

- higher prices (above world prices) that they have to pay;

- limited choice of consumer goods from restriction on imports of competing products; and

- in the Bangladesh context, inferior quality of domestically produced import substitutes resulting from persistent high protection.

Come budget time, the revenue authority is focused on mobilizing more revenue from taxes and tariffs, often mistakenly assuming that higher tax rates will yield higher revenues. Producer groups lobby hard to get direct taxes reduced as much as possible. As for indirect taxes like tariffs, their goal basically is to get higher tariffs on outputs they produce and lower tariffs on inputs which they source from imports or domestic suppliers. It is not difficult to postulate that tariff adjustments in the budget produces gainers and losers depending on which groups wield the most influence on policymakers.

It is important to keep in mind that interests of producers and consumers diverge, as producers like to see higher prices for their products while consumers want lower prices and more choice. Consumers, the largest stakeholder group, are all but absent from pre-budget consultations.

The urgency for a coherent national tariff policy

Why the need for a National Tariff Policy for Bangladesh? Because, while the Bangladesh economy has grown by leaps and bounds over the past 20 years, while exports have multiplied SIX times (from $6 billion to $36 billion) and merchandise trade (exports plus imports) has grown exponentially over the same period, the tariff structure remains antiquated, grossly inconsistent with the fundamental characteristics of a dynamic economy. Meanwhile, its main competitor, Vietnam, has an average tariff of about 5%, has demonstrated the most dynamic export performance over the past decade, and is signing FTAs with the largest trading groups in the world raising its free trade access to over 40% of world trade.

In the past 75 years since WWII, tariffs around the world have come down to reasonable levels (world average tariffs are about 6%) not to be counted any more as the major impediment to global trade. Research on impact of trade reforms (Irwin, 2019, Dollar and Kraay, 2001) has shown consistently that such reforms that include reduction of tariffs has had positive impact on economic growth and Bangladesh experience confirms that. The focus of multilateral institutions has now shifted to non-tariff barriers and improvement of trade logistics and payment systems to facilitate trade in goods and services. Nevertheless, occasional hiccups with tariffs do crop up, particularly in times of crisis, like the COVID-19 pandemic and the US-China trade tensions. In this scenario of evolution of trade and tariffs, Bangladesh emerges as an outlier where tariffs as a principal instrument of trade restriction have not lost its ground — at least, not just yet. In consequence, Bangladesh’s trade and development potential, widely acclaimed as exemplary, is not being realized. Research on Bangladesh economy (Sattar, 2012) reveals that tariffs are not just restricting imports but — as this report has argued — remain a major stumbling block to greater export expansion and its diversification.

No doubt, there has been progress in making the tariff structure more transparent and uniform to eliminate scope for malfeasance or unnecessary confusion in classification of imports. But much work remains. In the absence of a coherent strategy or principle for tariff setting, the historical record suggests a tendency for ad hoc imposition of tariffs on grounds that emerge from time to time. Though analysts can discern some general direction of tariffs – such as the pursuit of revenue – because of collateral impacts of tariffs, one finds the imposition of tariffs and para-tariffs, and adjustments over time, as being reactive rather than proactive. Conspicuous by its absence is a pro-development, business and export-friendly approach to the strategy of tariffs.

One positive aspect of tariff setting is the convention of making annual changes to tariffs and para-tariffs as part of Budgetary process. By and large, the Government (NBR) sticks to these annual adjustments, with few exceptions. This practice adds to the notion of stability of tariff policy. One more aspect of progress relates to the extensive pre-budget consultation with stakeholders whose recommendations are sought in making tariff adjustments. The problem lies in the fact that consumers – the largest stakeholder group affected by tariffs – are overlooked as the whole process is conceived as an approach to promote business and investment incentives in a private sector driven economy. The main stakeholders consulted include chambers and various producer associations whose interests are often in conflict with those of consumers. As explained earlier, consumers end up the losers in a process that imposes the burden of the protection tax on consumers. Therefore, one of the goals of a reformed tariff structure should be to balance consumer and producer interests.

Finally, a closer review of tariff setting following stakeholder consultations reveals a lack of a wholistic approach to overall tariff policy. Instead, one would find mostly ad hoc adjustment to tariff rates in response to stakeholder proposals that typically result in output tariff rates remaining largely unchanged while input tariffs decline (as stated in the preceding discussions). In consequence, the political economy of tariff setting leads to the one expected outcome – output tariffs remain stubbornly high while input tariffs record declining trend with effective protection on the rise, showing no sign of being phased out over time. The structure of tariffs and trends appear to perpetuate protection without regard to infusing competitiveness or efficiency over time.

The current approach to tariffs as an economic policy results in a tariff structure with never ending support for consumer goods production for domestic sales, a structure that favours import substitute production over exports with an inherent anti-export bias. Taken together, the ad hoc and episodic tariff adjustments during the Budget process results in a tariff structure that is not consistent with the policies relevant for a dynamically developing economy focused on export-led development with inclusive growth driven by the private sector. The need for a coherent National Tariff Policy thus becomes all the more pressing at a time when the economy must grow out of a pandemic shock and be prepared to meet the challenges of a highly competitive international economy.

At the outset it is critical to acknowledge the development context of the present exercise. Three decades ago, the Bangladesh Government embarked on a policy of trade liberalization embracing the development strategy of export-led growth, a policy that has yielded rich dividends in export success widely acclaimed by external analysts and multilateral agencies. Nevertheless, close scrutiny of the current tariff structure and trends reveal certain anti-development features that render it unfriendly to export performance and its diversification. The need for a coherent and pro-export National Tariff Policy has therefore become a national imperative.

The formulation of a coherent National Tariff Policy begins with the process of rationalizing and modernizing the tariff and protection structure with the objective of streamlining the import and export regime to create dynamism in business and investment, and to sustain rapid economic growth, as the nation prepares to attain 8% average GDP growth during the period of the 8th Five Year Plan (FY21-25) and prepares to graduate out of LDC status in 2026. The immediate task is to formulate a tariff structure that generates adequate revenue, accords reasonable protection to nascent domestic industries, without undermining dynamism in business and investment activity. Gradually lowering average tariffs and protection levels will be among the several key features of tariff modernization while keeping a watchful eye on the revenue consequences of such a move. Our analysis has revealed the possibility that if current tariff rates exceed the optimal rate, reduction of rates could even yield higher revenue, as was the case in the early years of trade liberalization in the 1990s. As demonstrated earlier, throughout the 1990s decade, as tariffs were scaled back, it is a matter of record that there was never a single fiscal year when customs revenue declined as a consequence of tariff reduction.

The key features of a coherent National Tariff Policy should include the following:

• To sustain robust export growth with diversification, and rapid industrialization with job creation, the structure of tariffs and other trade taxes must be modernized and made export-friendly, business and investment friendly.

• An effort should be made to adhere to the cardinal principles of a modern tariff regime – transparency, simplicity, and efficiency – by moving towards low and uniform tariffs (i.e. low dispersion), adopting a single rate for similar goods, by avoiding multiple rates at HS-6, with very few, if any, HS-4 codes having multiple rates.

• Tariff anomalies – a situation where input tariffs exceed output tariffs – should be meticulously avoided by adhering to long-established tariff slabs: capital goods (1%), basic raw materials (5%), intermediate goods (10/15%), and final consumer goods (25%, the top CD rate). These rates should be lowered gradually and methodically each year.

• The tariff structure has to be modernized and rationalized to make it consistent with evolving a trade policy befitting a rapidly growing economy that will shortly graduate out of LDC status on way to becoming an Upper Middle-Income Country.

• Because trade taxes significantly distort incentives to business and investment, Bangladesh should gradually make the strategic shift away from reliance on trade taxes to domestic taxes (e.g. income and corporate tax and VAT). Trade facilitation rather than revenue collection should be the dominant objective of a future customs administration.

• Policymakers should recognize that the tariff structure and export performance are not mutually exclusive. Tariffs, particularly protective tariffs, create anti-export bias in trade policy, significantly undermining incentives for exports and thwarting national efforts at export diversification. Rationalizing the protection structure through tariff modernization has also become imperative in order to infuse competitiveness and dynamism to our export performance. A priority trade and tariff policy agenda would be to rationalize tariff protection to balance incentives between exports and domestic production/sales of import substitutes. To the extent that the Government is required to impose or adjust tariffs for protection, the policy should be to make protection time bound and performance based.

• As a founding member of the multilateral regime symbolized by WTO, possibly with forthcoming reforms, Bangladesh’s tariff structure will have to gradually be made fully compliant with WTO rules, particularly as the economy moves towards graduation out of LDC status by 2026.

• Since Bangladesh average tariffs far exceed those of LMICs, a strategy has to be adopted to move closer to the LMIC average over the medium-term. We need to gradually adopt the kind of tariff structure that is found amongst most developing and Middle-Income Countries. Furthermore, the tariff structure must resemble that of a dynamic export-oriented developing economy. A beginning has to be made over the next four fiscal years (FY2022-25) while the country prepares to graduate out of LDC status in 2026.

• By 2026, the reliance on para-tariffs (SD, RD) for revenue or protection will have to be phased out. WTO rules require that CD be the only instrument of protection, and other duties and charges (ODC) are treated as tariffs. SD and RD, used predominantly as protection instruments (except for those on automobiles, alcoholic beverages, cigarettes) will have to be subsumed with CD upon graduation without exceeding bound rates. CD will then emerge as the main import tax of the future complimented with trade-neutral VAT.

• By 2026 or earlier, average nominal tariffs will have to be brought down to levels similar to other Lower Middle-Income Countries and/or comparators in the Asia-Pacific region.

This article is an abridged and edited version of a detailed research report prepared for the IFC-BICF of the World Bank Group. The views and opinions expressed in this article are drawn from the author’s research and practical experience in dealing with Bangladesh tariffs and must not be attributed to the World Bank Group or any of its subsidiaries.

Competent research support from PRI’s Ziaul Ahsan, Research Fellow, and Sr Research Associates, Sabrina Shareef and Promito Musharraf Bhuiyan is gratefully acknowledged.

References

Dollar, David and Art Kraay (2001). “Trade, Growth and Poverty”. Development Research Group, The World Bank.

Irwin, Douglas (2019). “Does Trade Reform Promote Economic Growth: A Review of Recent Evidence.” Peterson Institute of International Economics (PIIE) Working Paper, Washington DC, USA.

Prebisch, R. 1950. The economic development of Latin America and its principal problems, UN ECLA, New York. Also published in Economic Bulletin for Latin America, 7, 1962, 1–22.

Sattar, Z. (2020). “Assessing State of Industrial Protection 2020: Review of Effective Protection in Selected Sectors”. PRI study carried out under IFC implemented Bangladesh Investment Climate Fund II, Trade Competitiveness for Export Diversification Project, funded by UK’s FCDO.

Sattar, Z., Z. Ahsan, A.S. Yousef (2017). “Supplementary Duties, Protection and Revenue.” Mimeo, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI).

Sattar, Z. (2012). “Prospects for and Constraints to Export Diversification in Bangladesh.” Report prepared for the Asian Development Bank.

Singer, H. W. 1950. The distribution of gains between investing and borrowing countries, American Economic Review, 40, 473–5.

Pingback: How India and its South Asian Neighbours Fared During the US-China Trade War – Investment News Daily

Pingback: How India and its South Asian Neighbours Fared During the US-China Trade War – The Wealthiest Investor

Pingback: How India and its South Asian Neighbours Fared During the US-China Trade War – Invest Like a Bull