After the pandemic onslaught a strong recovery under way State of the economy 2021

By

Second year of the pandemic

The year 2021, the 50th anniversary of Bangladesh independence and 100th birth centenary of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was a milestone in more ways than one. Today, Bangladesh is no longer remembered as an impoverished and resource-poor nation subjected to frequent natural calamities. Rather, it is hailed by international analysts for its economic progress as a dynamic exporting economy, for its successful fight in reducing abject poverty of millions, for making significant strides in several aspects of human development relatively better than its peers, and even becoming an icon in disaster management for others to emulate. Bangladesh, at 50, has earned a respectable place in the comity of nations, no longer to be derided as a “basket case”, but to be surely acclaimed as a “development paragon”. Admittedly, there were and still are missed opportunities for doing even better throughout this long journey and beyond.

Economically speaking, 2021 also marks the 50th year of positive annual GDP growth without recording a single year of negative growth. The size of the economy at USD 400 billion is more than 50 times its size in 1972, with a per capita income over 25 times (USD 2500 against USD 90); food production today at 38.7 million MT is nearly four times 1972 production, making Bangladesh with 165 million near self-sufficient – unthinkable in 1972; exports at USD 38 billion in a competitive world market of 2021 has risen more than 100 times the 1972 value of USD 355 million. These should not be taken as statistics. Underneath these numbers are the hard toils of farmers and workers, risk-taking and management of first generation entrepreneurs, supported by Government policies that were by and large committed to the welfare of Bangladeshis throughout the decades. Progress today is the cumulative outcome of many congruent factors that worked to produce the result we witness.

For the economy, the year was marked by resilience in the face of an unprecedented global shock from Covid-19 pandemic followed by gradual but resolute economic recovery, a recovery that is still under way. While economies, large and small, developed and developing, crumbled under the weight of the pandemic onslaught, the Bangladesh economy did take a transitory hit, in terms of growth, poverty, and unemployment, but not enough to break from the steady-state growth path that was built into the foundations of the macro economy for the past quarter century. Barring any unforeseen resumption of another Covid surge or any “Black Swan” event in the near future, the economy appears poised for a strong recovery on the back of accelerating global growth as projected by IMF’s October World Economic Outlook (WEO).

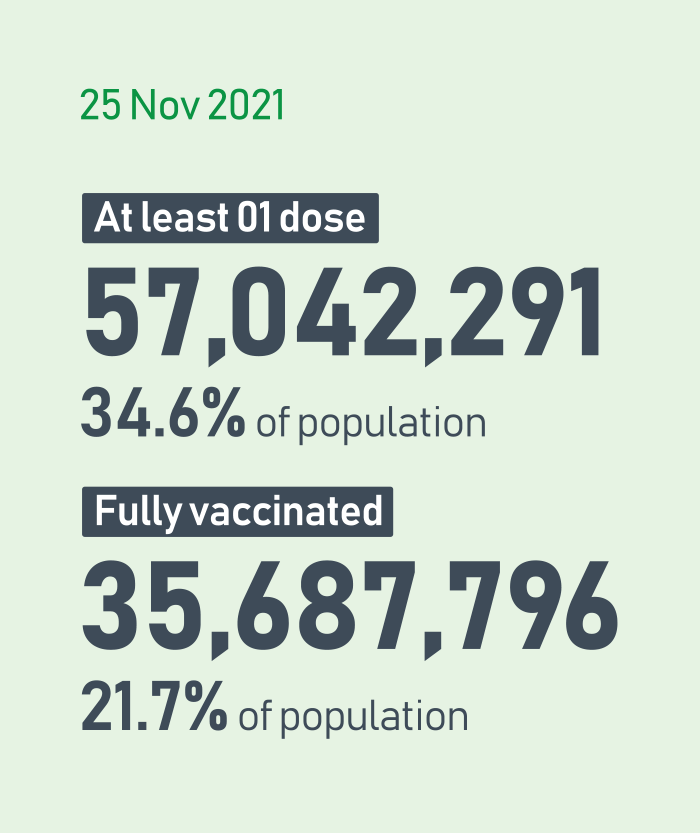

2020-2021 will be known in history as the years of Covid-19. The words “pandemic” and “vaccine” were chosen as words-of-the-year for the two years by Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Indeed this was a new phenomenon that rattled both Bangladesh and the world economy. But the pandemic is far from over. As the curtain falls on 2021 the Covid-19 pandemic impact is subdued but not extinguished. Thanks to advancement in modern medical science – the new messenger RNA technology — Covid vaccines were invented and manufactured in record time, giving rise to the next challenge: rapid distribution and impregnation. But the ominous rise of vaccine nationalism gave fodder to the global vaccine divide where rich countries held control over vaccines and financial resources when billions of people in the poorer regions of the world needed them just as much but lacked both vaccines and resources. With the change of administration in USA, the global governance of vaccine distribution under international (WHO) and national initiatives has been given new life, as it were. After some initial sputtering of mismanagement and vaccine shortages (actually happened in rich and poor countries alike) Bangladeshis appear to be settling down to a moderate stream of vaccines and vaccinations to have an efficacious deterrence on the spread of infections to allow gradual resumption of the “old normal” in Bangladesh society. To our advantage, unlike so many developed societies, mask mandates are being observed without incident but the coverage of fully vaccinated eligible population only crossed 21% as of 25 November. There is still a long way to go in order to reach some 70% of the population in order to reach what is called “herd immunity” for the entire nation. Several millions of low-income Bangladeshis inhabit the “bastees” of big cities living in unhygienic conditions without adequate vaccination coverage, or observing social distancing or other preventive measures. Yet there is no report of massive outbreak of infections since the start of the pandemic in 2020. This presents a scientific enigma that will need careful research to understand the reason for the immunity of bastee population.

As of this writing, global pandemic governance is once again rattled by the sudden appearance of a new variant of the SARS-Cov2 virus, named Omicron. First discovered in South Africa, this variant has more than 30 mutations in the spike protein (double that of Delta), and has been described as a variant of concern by WHO as preliminary research shows it to be more transmissible and could perhaps defy the protection of existing vaccines. That has to be seen as expeditious research is under way to develop and manufacture effective deterrents, though WHO hastens to add that, given the advancement of knowledge, the sky is not falling on us. Let fingers be crossed but a modicum of uncertainty about the future looms as scientists and infectious disease experts talk of potentially more variants mutating out of the SARS-Cov2 virus.

Post-pandemic global economic recovery

The magnitude of economic disruption and lives lost makes the Covid-19 pandemic a once-in-a-century event. A global health-cum-economic crisis was also a first though it may not be the last as visionaries like Bill Gates prognosticate that more such events are likely to follow. The economic fallout of this crisis shook the entire global economy with profound implications for Bangladesh’s short-, medium-, and long-term economic prospects. Arguably, financial and economic globalization and the inter-connectedness of peoples across the world have a role to play in making this a global pandemic, rather than just a regional or national outbreak.

Unlike the protracted but sluggish recovery following the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, indications are that the present global recovery will be much stronger thanks to the lessons learnt from the previous crisis. In particular, the stimulus package and monetary easing response to the health-cum-economic crisis was immediate and massive by historical standards, not unduly constrained by rising fiscal deficits or public debt. No doubt policy choices this time were more difficult, with multidimensional challenges, including subdued jobs recovery, supply chain disruptions, rising inflation, food insecurity, the setback to human capital accumulation, and climate change. While advanced nations could resort to monetary accommodation and fiscal expansion the scope was much more limited for developing nations thus exacerbating the economic divide.

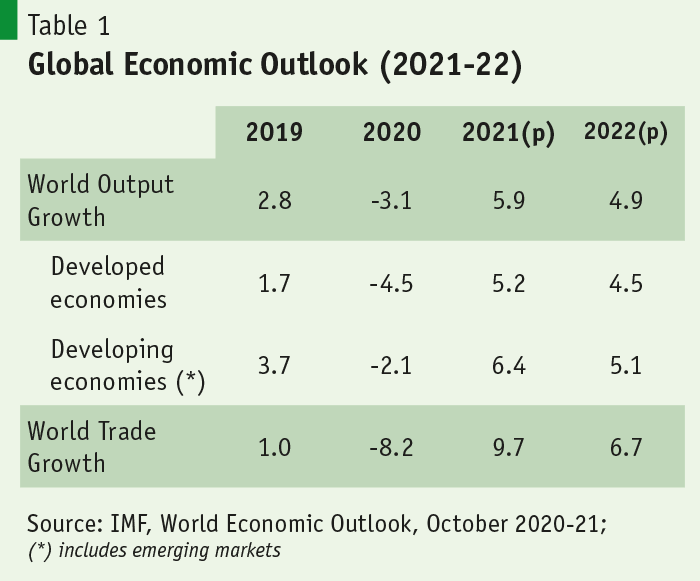

Nevertheless, the outcome so far has been mostly positive, inflationary developments notwithstanding (discussed later). Data shows global output and trade growth to be significantly higher this time (Table 1) compared to the sluggish trends for a whole decade in response to the modest stimulus launched by the rich nations in 2009 onwards which neither gave a boost to the developed economies nor to the emerging or developing ones. Slow global growth of 2-3 percentage points became the “new normal” since 2010. Notably, world trade growth which exceeded and drove output growth for 60 of the 70 years after WWII fell behind output growth. That trend has thankfully reversed in response to the new post-pandemic stimulus – a sign that the initial protectionist impulse has abated enough to fuel economic recovery worldwide.

According to IMF’s latest projections, global output is projected to grow at 5.9% and 4.9% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The recovery is expected to be boosted by robust trade growth of 9.7% and 6.7%, respectively, despite supply chain bottlenecks revealing pent up global demand that is fueling recovery. Though global growth is projected to moderate beyond 2022, advanced economies are expected to exceed pre-pandemic output levels stemming from the massive fiscal infusion into the US economy by the Biden administration. The only uncertainty arises from the output losses and sluggish growth in emerging economies like China though forecasts for India in the near term appears highly optimistic (8.5-9.5 range).

The specter of inflation has become a major headwind for future prospects of the global economy. US inflation crossed 6% in October, the highest in 30 years. Similar price appreciation is evident in most developed and some developing economies, including Bangladesh. The source of the problem lies in pandemic-related supply-demand mismatch as a fast-paced demand recovery overwhelms supply-chain resumption capacities. Though most analysts cite this inflation as transitory, inflationary pressures could persist if pandemic-induced mismatch continues longer than expected. Such a prospect could stymie output and employment growth. Yet, going forward fiscal policy will have to remain expansionary to accommodate health care related spending as priority in addition to financing social protection. Likewise, monetary tightening will have to be avoided until there is clarity on price dynamics or the risks of rising inflation expectations become tangible. This complicates the role of monetary policy in affected countries as policymakers have to walk the fine line of both controlling inflation and supporting economic recovery through expansionary monetary policy.

Finally, policymakers across the spectrum also need to comprehensively plan post-pandemic economy which involves reversing the pandemic-induced setback to human capital accumulation, enabling new opportunities related to green technology and digitalization, mitigating inequality, and ensuring sustainable public finances.

The global pandemic has tested the resilience of nation-states and the global political and economic systems like no other crisis in modern history. Not only has it forced policymakers to find the difficult balance between lives and livelihood, it also allowed the global community to witness the structural weakness across global institutions to deal with this calamity both decisively and collectively. With more than 250 million cases and 5 million deaths – Covid-19 demonstrated the vulnerability of the global society to pandemics and its grave social and economic aftermaths. What has become abundantly clear is that the Covid-19 is a global disease and needs global effort to be eradicated. The pandemic will not be extinguished anywhere until it is eradicated everywhere.

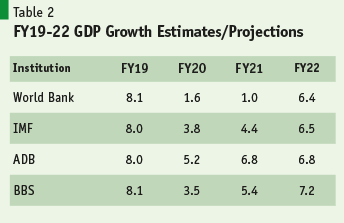

Given this backdrop, development partners have made their own assessments of the magnitude of output shock faced by the Bangladesh economy and, in light of the emergency stimulus package and observed recovery of external trade and remittance inflows, they have indicated disparate GDP growth rates for FY20-FY22 (Table 2). Whereas the leading multilateral agencies, WB, IMF, ADB, made growth projections for FY19 that were close approximations of the official estimate of 8.1%, that unanimity is understandably missing in the current projections because of the disruptions and consequent delays in collating data and the prevailing uncertainty reigning over domestic and global landscape. Both WB and IMF are far more modest in their estimates and projections compared to ADB with the WB making highly pessimistic estimates for FY20-21 except for FY22, when WB along with others reveal greater confidence with regard to the drivers of Bangladesh economic recovery.

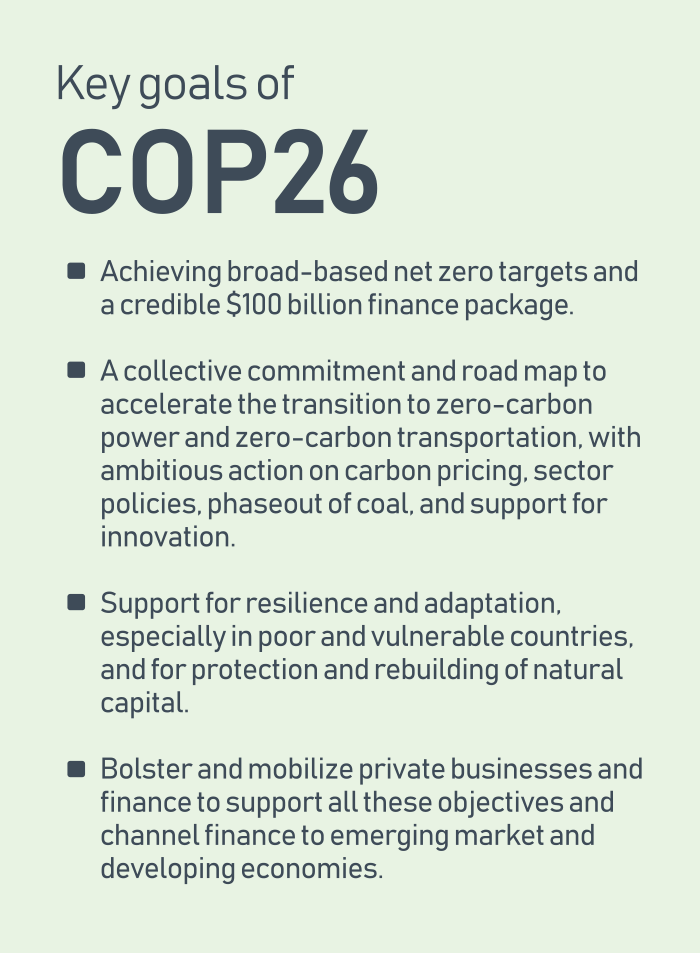

COP26, Coal phase down and the $100 billion climate financing

Global warming of 1.1oC has already taken place since the advent of the First Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. At the present pace of GHG emissions around the world, if nothing is done to stem the emissions, global temperatures could rise by 3oC by the end of the century. That would have disastrous consequences on lives and livelihoods around the globe – with sea level rise, air pollution and so on. Hence, the goal of COP21 and the follow up COP26 was to limit global warming to 1.5oC by 2050 by setting targets for net zero carbon emissions for the large emitters by 2050.

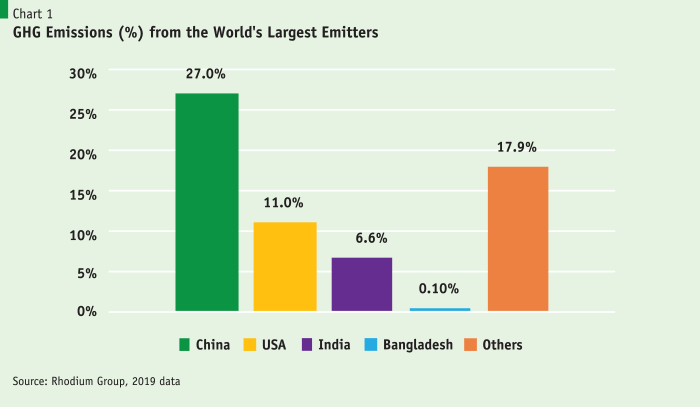

For the first time, China’s GHG emissions exceeded the 14 gigaton mark in 2019, hitting 14,093 million metric tons of CO equivalent (MMt CO2e). This represents a more than tripling of 1990 levels, and a 25% rise over the past decade. Consequently, China’s contribution to the total world emissions of 52 gigatonnes in 2019 increased to 27%. After China, the world’s next largest GHG emitter was USA (11.0%), followed by India (6.6%). The next major GHG emitting countries were EU-27 (6.4%), Indonesia (3.4%), Russia (3.1%), Brazil (2.8%) and Japan (2.2%) – added and categorized under ‘Others’ in Chart 1.

Bangladesh is among the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries. Between 2000-2019, Bangladesh has ranked 7th on the global Climate Risk Index. A delay in taking urgent measures to align with 1.5°C compatible pathways and risking a 3°C global warming scenario could cost losses in Bangladesh GDP by 2050 of up to -15% and by 2100 of up to -70%, according to Climate Analytics. The challenge to avert this possibility is daunting. Which is why the world assembly of 193 nations in Glasgow in early November was potentially a game changing event and a critical one for Bangladesh. Was it really? What were the main take aways?

Although Bangladesh still has an LDC status and is not under obligation to submit an Nationally Determined Commitment (NDC) or monitoring reports every two years on progress towards achieving its NDC targets, in 2021 Bangladesh has updated its INDC submitted in 2015 with an unconditional target of reducing 27.56 MtCO2e and conditional GHG reduction target to 61.9 MtCO2e from a BAU scenario of 409.41 MtCO2e by 2030. In 2018, it was estimated that Bangladesh emitted 221 MtCO2e which included LUCF and per capita CO2 emissions in 2019 was at 0.66 tCO2e. This is negligible in the global context; however, it is likely that the BAU scenario of 409.41 MtCO2e estimated by GoB could even be exceeded given GDP and energy growth projections in the country.

The COP26 conference in Glasgow had one overarching goal for the weeks-long event: to “consign coal power to history”. Coal generates 40% of the world’s electricity needs, as well as 46% of global carbon emissions, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Countries must reduce coal’s share in global power generation to less than 1%, as IEA suggests, in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. The countries had pledged for the first time to “phase out” the use of coal-fired power, and stop building and issuing permits for new coal plants at home, eventually shifting away from using fuel. But, due to opposition from the largest users of coal power – China, USA, India – the final reference had to be watered down to “phase down”. Meanwhile, a reference to eliminating fossil fuel subsidies was also toned down to ending “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies, leaving plenty of space for interpretation and negotiation.

One of the conference’s biggest failings was the lack of a concrete mechanism to help frontline climate-vulnerable communities and emerging economies rebuild and recover from catastrophic weather events and receding coastlines. The US$100 billion-per-year commitment to assist vulnerable nations adapt to climate impacts, which was pledged 12 years ago, has failed to materialize—a missed milestone underlined in the statement with “with deep regret”. The declaration also stifled the global south’s demand for clear, direct language on climate financing. Instead, it created options for debate, reflection, and “technical assistance.” Overall, campaigners demanding a stronger commitment to climate justice—not only for countries, but also for cross-border groups such as youth, indigenous peoples, women, racial and ethnic minorities, and others—felt betrayed.

But the fact that the Glasgow climate negotiations did not completely collapse gives grounds to hope for more progress from world leaders and wealthy private sector stakeholders. So, where do we go from here? What is the path forward? In the coming year, major GHG emitters must increase their 2030 emissions reduction targets to align with 1.5 degrees Celsius, more robust approaches are needed to hold all actors accountable for the many commitments made in Glasgow, and much more attention is needed on how to meet the urgent needs of climate-vulnerable countries to help them cope with climate impacts and transition to net-zero economies. The Glasgow Climate Pact sets out the key steps to do so. But it is only until this is accomplished that we will have a real chance of meeting the 1.5 degrees Celsius objective and creating a more secure and just future for all of us.

GDP growth climbing back to pre-Covid trajectory

Growth in the years of the pandemic has been subject to controversy in Bangladesh. While most economies around the globe experienced significant negative shocks from the pandemic impact resulting in negative GDP growth and recessionary contraction, first growth estimates by BBS came out looking somewhat optimistic. Later that has been appropriately revised to more reasonable levels. However, despite the pandemic shock, Bangladesh economy did not go into negative growth like many of its peers. Though battered, the economy suffered negative growth shock but did not fall into a recession which would require recording of negative GDP growth. In developed economies (e.g. OECD) where quarterly GDP is published, it takes two consecutive quarterly decline to register officially as the onset of a recession. There is no official definition of a recession in Bangladesh as negative growth never happened but it is possible to consider negative GDP growth, if it ever happened, as the indicator of a recession.

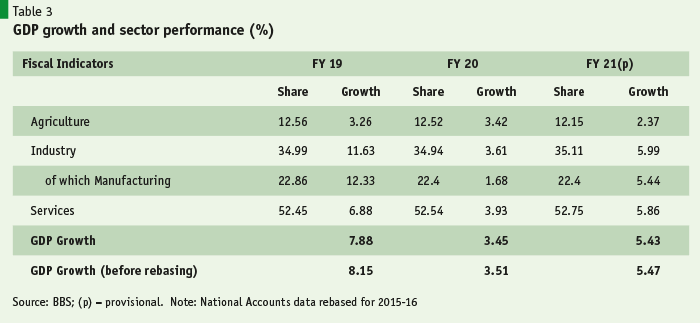

As Covid-19 swept across borders, like most economies – developed and developing — Bangladesh economy was pummeled by the output and trade shock that reverberated across the globe. Until the pandemic hit in March 2020, the Bangladesh economy was chugging along at an accelerated pace of 6-7% GDP growth during most of the decade of the 6th FYP and 7th FYP, between FY2011 and FY2019. Global analysts monitoring Bangladesh’s growth acceleration noted that its growth rate was not only rising but was the most stable among the developing world. Covid19 crisis drilled a crack in that stability. Like so many other nations the Bangladesh economy was not spared the eviscerating onslaught of the Covid19 pandemic. It was a combination of demand and supply shocks that ravaged the length and breadth of the economy leaving few if any sectors of activity unscathed in 2020. Economic activity gradually started picking up in late 2020 and much of 2021. Annual GDP growth which dipped to 3.45% in FY20 rose modestly to 5.4% in FY21, and is showing signs of approaching the targeted rate of 7.2% set for FY22 (Table 3).

Following the guideline of UN System of National Accounts (SNA) Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics recently disclosed updated GDP statistics after changing the base year to 2015-16 from 2005-06 – a 10-year updating method. Such updating to reflect new economic activities that emerged in the ten years between 2005-06 and 2015-16 is consistent with UN SNA methodology though it does give a one-time upward shift to GDP numbers, with only marginal change in growth data. Given the new base year, BBS has estimated the size of the country’s GDP at US$411 billion in FY2021 with per capita income reaching US$2,554.

So, despite the pandemic shock on the economy, output growth in agriculture, industry, and services, all remained positive but lower than most years in the recent past leading to modest GDP growth in FY20-21. But the expectation for FY22 is that the economy will have returned to its pre-pandemic growth trajectory with a plausible targeted GDP growth of 7.2%. Several key drivers of growth, namely, agricultural and industrial production, services activities, exports and remittances, all appear to be on a strong uptick based on the latest data as of November 2021. Assuming that another Covid surge is not on the cards (advent of Omicron could upset the cart) the targeted growth should be within reach.

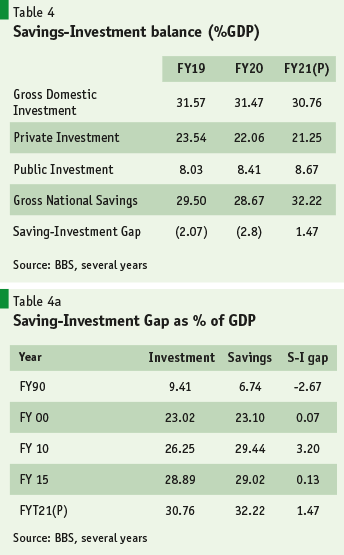

A quick review of the economy’s savings-investment balance is worthwhile. The economy’s growth is still driven by investment rather than consumption. Relying on past data the economy’s capital-output ratio (which defines investment requirement for output growth) works out to 4.5 so that to achieve targeted growth rates of 7-8%, the economy needs investment-GDP ratio of 31.5% or more. As data in Table 4 reveals, the economy is getting close to achieving that requirement (30.7-31.6 in FY19-21). However, the share of private investment has remained sluggish for the past 5 years while public investment has picked up the slack.

Another notable feature of the savings-investment balance is the difference, called the savings-investment gap. For only a few years do we find the gap to be negative, implying an excess of investment over gross national savings (includes remittances) – what should be the case for a developing economy requiring massive investment in infrastructure. The fact that we find an excess of savings over investment for too many years gives an indication of under-investment of available savings. This is also reflected in the balance of payments data, where a current account surplus is recorded for 13 of the 21 years since FY2000. Indeed, the economy has lot of space for boosting investment with domestic and/or external resources.

External trade on way to post-pandemic recovery

Given the global prospects of output and trade growth in 2021, 2022, and beyond, as projected by IMF, the outlook for Bangladesh trade for the near term should appear optimistic. Export performance during the first four months of FY2022 reveal broad-based and robust pick up in exports at 22% year-on-year of both RMG and non-RMG exports. This follows the strong recovery of 15% in FY2021 after the Covid-induced dip of 17% in FY2020. The trend is encouraging in these uncertain times signifying improving global demand for exports with rapidly shifting geopolitical landscape in GVCs and product sourcing. Though decoupling from trade with China will take time there is evidence of a growing mindset for reshoring production in the developed countries. It would be in Bangladesh’s long-term interest to undertake fundamental reforms in trade policies (greater trade openness) in order to position itself as a competitive sourcing destination at least for labour-intensive manufactures over the medium-term and tech-intensive products (e.g. electronics) over the long-term.

Much of Bangladesh’s economic growth has been export-led with continuing remittance inflows. But for more than forty years or so, Bangladesh has been reliant on a mono-product success, and that too on a narrow range of relatively low value added RMG products. Export diversification continues to challenge policymakers. Also there is need to diversify into more complex and high end RMG product and move up the value chain. That calls for substantial overhaul of trade policy to shift the balance of incentives away from domestic sales in favour of exports. Rationalizing the protection structure is an absolute necessity.

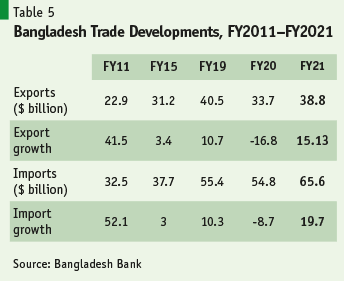

Until the pandemic hit in March 2020, the Bangladesh economy was chugging along at an accelerated pace of 7–8% GDP growth during most of the decade of the 6th FYP and 7th FYP, between FY2011 and FY2019. Merchandise exports, led by readymade garments (RMG), recorded double-digit growth of 11–12% per annum for two decades (FY1990 through FY2011) but slowed to about 6–7% thereafter. For the past 20 years, merchandise trade (exports and imports) has been growing at an accelerated pace. It more than tripled in the first 10 years of the 21st century, from $15 billion in FY2001 to $55 billion in FY2011, and then approached the historic milestone of $100 billion in FY2019 (Table 5). Covid19 shock in FY20 was a setback to these promising trends in the trade scenario. That scenario changed in FY21 as recovery took shape with further deepening in the first quarter of FY22.

Thus far, Bangladesh’s Covid-19 impact on exports appears muted, as the export slump in the initial months of the Covid-19 onslaught was not persistent to cause any serious damage to foreign exchange earnings, thanks to revival of cancelled export orders, import slowdown and record remittance inflows, all contributing to a comfortable level of foreign exchange reserves. However, that should not lead to any complacency with regard to the need for vigorous efforts to set the house in order in order to take up the challenges that post-Covid-19 world economy will be posing for Bangladesh. The sluggish import performance has started to rebound and exports need to grow on a diversified product basis to provide support to the acceleration of manufacturing growth and employment.

After the negative global trade shock of 8% world trade experienced a sharp rebound in 2021 (9.7%) which is expected to modestly taper out in 2022 (6.7%). These global growth rates are far stronger than what we have seen during the post-GFC recovery. As Bangladesh exports did fine even with the sluggish global recovery last time, we should be encouraged by the signs of strong pick up in trade to expect robust demand for our exports in the coming months. Though the crisis hit hardest regions that are our leading export destinations – USA, EU – the pick up in 2021-22 also appears strong in these same markets thanks to massive stimulus spending and monetary easing that has kept jobs and income (hence consumer demand) on a higher sustainable path. Meanwhile, what we need is for our trade policy to be revamped to gain any traction in export recovery in 2022 and beyond.

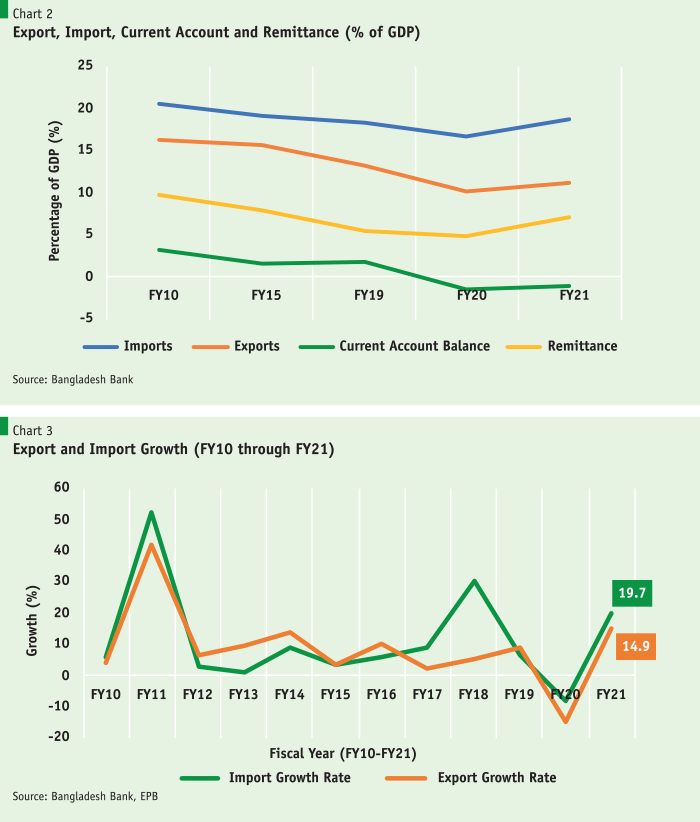

Trade has been an engine of growth and major source of job creation for Bangladesh. Ever since the trade liberalisation episode of the early 1990s, both trade and GDP growth, along with poverty reduction, have experienced a secular improvement decade after decade. Trade openness, measured by the share of imports and exports to GDP, climbed up substantially since the trade liberalization policies of early 1990s. Consequently, Bangladesh today is far more integrated with the world economy than it was in the early 1990s. COVID-19 came as a shock to exports as importing nations came under lockdown, and retail outlets and buyers started cancelling export orders. That scenario appears to be changing for the better as all the signals are pointing to a strong export recovery.

Indeed, this crisis could be the shock that becomes the trigger for some structural reforms that have become due in the trade area, particularly to address the challenges of global competitiveness on the one hand and domestic trade policy conflicts that creates anti-export bias sapping incentives for non-RMG exports with consequent lack of export diversification.

To put the Covid19 impact on external trade and payments in perspective the following charts (Chart 2-5) give an overall picture of trade and payments developments, including the state of official foreign exchange reserves, over the past decade leading up to and beyond Covid-19 crisis.

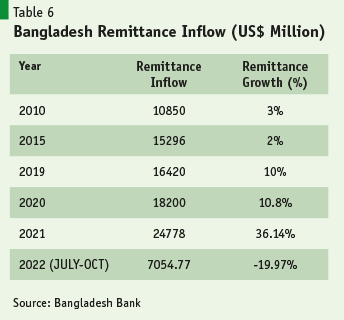

Remittance inflows hit record amidst Covid19 pandemic. Remittance, the income and savings of migrant workers, is unquestionably a strong driver of growth via its impact on consumption and investment spending as well as its singular contribution to Bangladesh’s sustainable current account balance in the wake of rising demand of foreign exchange for import of goods and services to meet development requirements.

Remittance inflows arise from export of factor services. After merchandise exports, remittance inflows make up the second largest foreign exchange source for Bangladesh. Migrant workers (under Mode 4 of GATS) and their remittances have played a pivotal role in reducing poverty as well as fueling growth in Bangladesh. The Ministry of Expatriate’s Welfare and Employment estimates that 12% of our labor force (about 8 million) of 65 million are employed abroad. One estimate by the RMMRU (Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit) puts the current stock of Bangladeshi migrants worldwide at 11.5 million.

In FY20, a major uptick in remittance inflows was evident in consequence of the 2% cash incentive offered to migrant workers remitting through legal channels. Then Covid19 pandemic struck, along with a collapse of oil prices, causing host countries in the GCC to shed migrant workforce. But that failed to stem the rising tide of remittance inflows through official/banking channels contributing to accumulation of official foreign exchange reserves. Hopefully, the Covid19 impact on employment of migrant workers will be a temporary shock. As oil prices are already on the rise, the prospect of retrenched migrant workers returning to employment in the GCC countries appear brighter.

The inflow of remittances hit a record high of about $24.77 billion in fiscal 2020-21 compared to the $18.2 billion in FY2020 as the BB has taken measures to streamline the legal channels for encouraging Non Resident Bangladeshis (NRBs) to send money to the country. Expatriate Bangladeshis sent 36% more remittance in FY21 – a bumper rise that will be difficult to sustain. So, in the first four months we see a significant dip in remittance (-19% y-o-y). The deep dive is partly explained by the wide divergence between foreign exchange bank rate (Tk.85/$) and curb rate (Tk.90/$) – a clear signal to shift from legal channels to hundi (migrant workers are familiar with the profitable channels of transfer). Nevertheless, the flow in FY22 is expected to be higher than the pre-pandemic level.

Steady flows of remittances from migrants have had important stabilizing effects on the balance of payments. Despite chronic trade deficits, the current account balance of Bangladesh has turned positive with the rise of remittances. Remittances have contributed significantly to the sustainability of our external balance with accumulation of foreign exchange reserves.

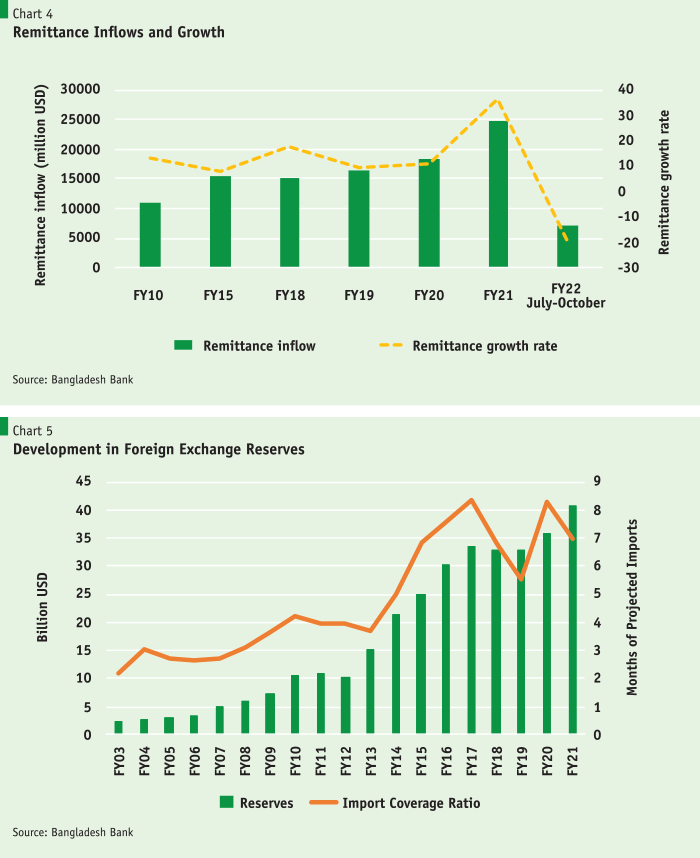

Foreign exchange reserve accumulation hits record. A combination of earnings from exports and remittances has enabled the country’s foreign exchange reserve to witness a record of over $46 billion for the first time, amid the Covid-19 pandemic. The central bank is optimistic that the trend suggests further reserve accumulation as import bills are being adequately covered by FE earnings. However, although reserve growth is indicative of economic strength for Bangladesh, its management can pose a great challenge in the coming days amid the pandemic. Based on the BOP surplus of USD 9.3 billion, the foreign exchange reserves reached a record high of USD 46.4 billion, and the import coverage of the reserves stood at 7 months of imports as end of June 2021 which appears adequate for Bangladesh to cope with its import bills in these trying times. A robust pick up in trade (both exports and imports) is evident since the early days of 2021, putting downward pressure on the exchange rate. To keep the exchange rate from depreciating Bangladesh Bank has had to intervene pumping some $1.7 billion into the market, thus leading to some decumulation in foreign exchange reserves.

Trade policy remains biased against exports and must be reversed. For Bangladesh, the preponderance of research evidence points to the need for undertaking significant reforms in the structure and trends of tariffs in order to make them more export-friendly, ensure export competitiveness, while bringing more dynamism into the business and investment environment. Research on the vast range of non-RMG exports has confirmed that there is no lack of competitiveness for a vast swath of labor-intensive manufacturing products. But the trade policy regime and resulting tariff structure of Bangladesh is skewed in favor of import-substituting activities resulting in a substantial anti-export bias. RMG production exists with a “free trade enclave” insulated from this anti-export bias, primarily through the duty-free import system under Special Bonded Warehouse (SBW). But producers who cater to both exports and the domestic market face inherent policy bias against exporting activity when they find domestic sales far more profitable than exports. The government, in recent years, selectively provides such facilities like SBW (previously restricted for 100% export-oriented firms like RMG) to exporting firms that satisfy a critical minimum export volume, thus mitigating some of the dis-incentive from a high tariff regime. Nevertheless, a major challenge in the future will be to address this issue from it hurting emerging and potential exports, thus serving as a policy constraint to export diversification.

Presently, tariffs and para-tariffs are used as the main instruments of protection. Para-tariffs are defined as all import taxes, other than custom duties, having a protective effect. Supplementary Duties (SD) and Regulatory Duties (RD) are the main para-tariffs in the Bangladesh tariff regime. Supplementary Duties (SD) were first applied on imports in 1991 under the VAT and Supplementary Duty Act of 1991, as a trade neutral tax (i.e. applied equally on imports and domestic import substitutes with no protective effect) with the express objective of protecting revenue from the previously high taxation on so-called “luxury goods”. In course of time, however, the trade neutral aspect of SD appears to have been abandoned by reducing or eliminating the domestic part of the tax, while leaving the import component in tact with the result that, for all practical purposes, SD, by and large, became a protective tax. In addition, another para-tariff, Regulatory Duty (RD), was added on an annual imposition basis but seems to have earned a permanent character. For NBR, SD and RD are ostensibly revenue instruments and, for the most part, imposed on tariff lines that are already subject to the top rate of CD.

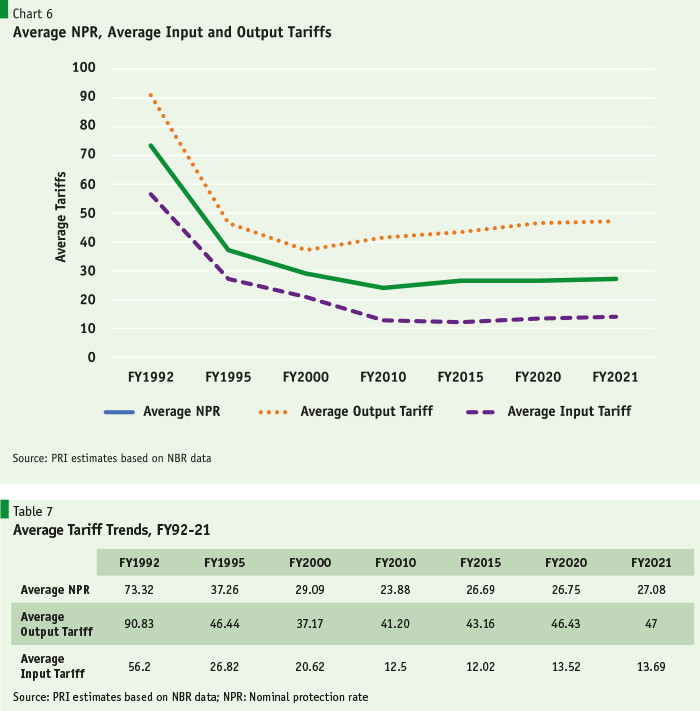

The tariff trends (Table 7) 0reveal some striking features that are relevant for policymakers to take note. Though average tariffs trended downward between FY1992 and FY2020, the sharp reduction in average NPR (a measure of nominal protection) over the 1990s decade appears to have tapered off during the subsequent two decades. The sharpest reduction in tariffs occurred during 1992-2000. A close examination will reveal that much of the reduction in average NPR in the past 20 years was due to reduction in average input tariffs which declined to 13.5% in FY20 from 20.6% in FY2000, while average output tariffs rose from 37% to 46.6% (Fig.5). This is a clear indication that effective protection levels, already high by international standards, have increased and was confirmed by a recent PRI study. What is problematic is that tariff protection and export performance are not mutually exclusive events. PRI research has revealed that, in the Bangladesh context, such high protection seriously undermines export performance and its diversification.

Progress in trade facilitation in high gear. Tough degree of trade openness in Bangladesh raises questions, there is strong private-public joint initiative to move trade facilitation into high gear. Recognizing the importance of deepening trade, Bangladesh has ratified WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) on 27 September 2016, and has since then taken up a number of trade facilitation measures including introduction of a trade information portal where all rules, regulation and statutory orders related to trade are made available to improve the accessibility, predictability and transparency of the country’s trading laws and process, Modernization of Customs policy (advanced stage of approval) in compliance with Revised Kyoto Convention, Standards to Secure and Facilitate Trade (SAFE) Framework of Standards, introduction of risk management in customs clearance, etc. Through continuous reforms, the number of pre-clearance signatures has gone down to less than 5 from a previous 25 signatures required, significantly bringing down export clearance time, while efforts are ongoing to further reduce procedures and release time through automation. NBR is presently migrating to an upgraded version of ASYCUDA World for greater data exchange facilities to streamline intra-agency communications and clearance process. The ASYCUDA World system has demonstrated some functionality to gather information involving Bill of Lading, Bill of Import, Bill of Export, Container Tracking, Release Orders or NOCs once related agency has completed their regulatory duties.

The government’s commitment and efforts were further strengthened with support from multilaterals and development partners like World Bank, Asian Development Bank, International Finance Corporation (IFC) and USAID, who had been actively working on multiple levels towards facilitating trade. IFC’s Trade Competitiveness for Export Diversification (TraCED) project under the BICF II has undertaken some pioneering reform activities and interventions in Bangladesh, working closely with the National Board of Revenue (NBR) in an effort to reduce time and cost of doing trade through simplification of procedures where possible. IFC helped Bangladesh Customs develop a comprehensive Customs Modernization Strategic Action Plan.

Fiscal prudence maintained despite Covid shock

The three main pillars of Bangladesh’s remarkable economic journey include fiscal prudence, social progress (poverty reduction and human development), and export performance. FY21 budget performance and FY22 budget program appears not to have deviated from that solvent path to keep us, according to US President Joe Biden, “a country of great hope and opportunity”, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi confirming that Bangladesh is finally “showing the world its potential”. Maintaining fiscal prudence in the times of Covid19 without pruning expenditures for the mega infrastructure projects and expanded social protection programs has been a challenge for the Ministry of Finance which will have to be commended for being able to strike the required balance.

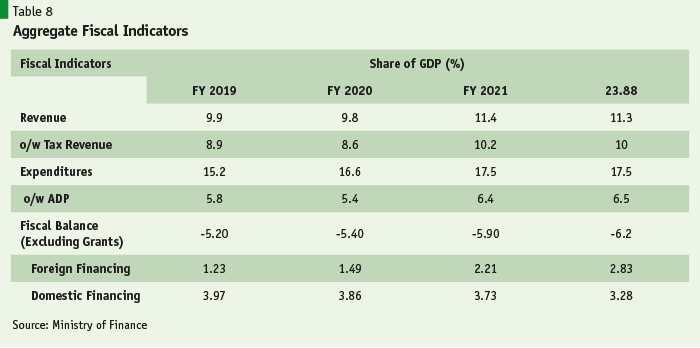

No doubt Covid19 crisis has strained but did not break Bangladesh’s otherwise sustainable fiscal balance. A sound fiscal policy framework has been the cornerstone of Bangladesh’s well admired development achievements. Low government deficits, relatively low public debt and debt servicing, avoiding inflation and exchange rate volatility, providing financial resources for private investment, public expenditures on primary education and preventive health, rural development and infrastructure all enabled growth and human development and the rise of a dynamic private sector. Those fiscal strategies are still on track despite that fact that growth decelerated sharply in FY2020 due to the pandemic which threatened to upset the fiscal cart. Thanks to the fiscal interventions (stimulus spending and monetary accommodation) economic recovery is under way which has also boosted fiscal resources (Table 8).

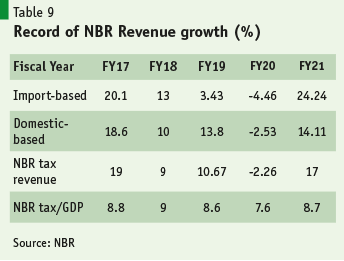

Oddly enough, tax revenue mobilization (NBR taxes in particular) got a significant boost from taxes paid by large corporate taxpayers in FY21. NBR revenues posted a 17 per cent growth in the just-concluded fiscal year (FY21) resulting in a significant rise of 1.6% in the tax-GDP ratio with revenue-GDP ratio crossing 11% for the first time in 6 years (Table 9). The National Board of Revenue (NBR) managed to collect Tk 2.56 trillion in FY21 against Tk 2.18 trillion in the previous FY, according to the provisional figures.

PRUDENT MACROECONOMIC MANAGEMENT. In the developing world Bangladesh has earned acclaim for its prudent macroeconomic management for nearly three decades. That economic strategy has worked to ensure macroeconomic stability, both internal (sustainable fiscal deficit) and external (sustainable current account balance). And macroeconomic stability has been the fulcrum on which rapid GDP growth was engendered. Central to this stability has been the budget deficit which has been restricted to 5% of GDP or less since the 1990s. Only after the inclusion of Covid-19 stimulus packages in FY21 and FY22 Budgets do we see a rise in the estimated fiscal deficit to 6% of GDP. Financing of the 6.2% deficit will be 47% from external sources (mostly multilateral loans) and 53% from domestic sources (banking system and the public). Counting on the higher commitments from multilateral agencies and the uptick in FY21 the Finance Ministry appears a bit more optimistic this time about receiving external finance.

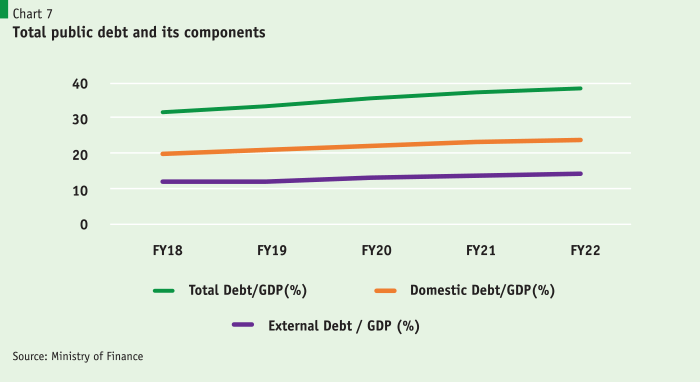

Budget deficits create public debt. Public finance literature indicates that fiscal deficits are considered in the sustainable range when such deficits leave the public debt-to-GDP ratio unchanged. For developing economies, a 5% of GDP fiscal deficit falls in that category. In the case of Bangladesh, we see fiscal deficits under 5% of GDP from FY1991 (-2.2%) through FY2019 (-3.9%). During that period, public debt-GDP ratio declined from 45% in FY91 to 35% in FY19 (Fig.6). This indicates that not only were the Budget deficits sustainable they were even better than that as they were well below 5% until FY19 thus leading to a secular decline in public debt-GDP ratio over time. With rising GDP growth every decade, Bangladesh could have engaged in higher public spending with higher deficits without upsetting the cart of macroeconomic stability. So the higher deficit targets of around 6% of GDP in FY21 and FY22 are well within sustainable range, provided effective monetary management is activated to keep inflationary pressures in check.

FISCAL PRUDENCE AND PRIVATE SECTOR. Despite the pandemic the Government’s decision to limit the FY22 budget deficit to 6.2% of GDP (Taka 2.14 trillion) is symptomatic of the preference for fiscal prudence over profligate spending particularly when it is aware of the logistical limitations in reaching targeted beneficiaries. Agreed, there was a genuine need for a much higher and wider payout of cash support to the poor whose numbers rose substantially due to the pandemic. The cautious fiscal approach which comes from a long period of prudent fiscal management which, to be fair, has also yielded dividends over the years.

To be sure, regularly limiting pubic spending to the constraints imposed by sluggish tax collection has actually left space for the private sector to borrow from the financial system and invest. Fiscal prudence prevented “crowding out”. True, weakness in the banking and financial system that produces the ubiquitous non-performing loans does take away some of the shine from productive investment. Yet, even within the constrained domestic credit environment, the private sector was able to borrow and play a dynamic role in building the foundations of an economy that is being hailed by international analysts as a “standout” case in South Asia (columnist Mihir Sharma, Bloomberg). The net result of fiscal prudence is that our debt and deficits are sustainable and under control. All this positivity was built on the back of continued macroeconomic stability. Budgets, current and past, have contributed to this comfortable situation. Imagine where macroeconomic stability would be if budget deficits were running at 7%+!!

Diesel price hike. Raising the price of diesel, though unpopular with users, was a pivotal decision towards a greener Bangladesh – a long-term goal that Bangladesh has been steadfastly promoting. By taking this first important and bold step to increase diesel price, the government has given a signal that it is serious in its ambitions of growing a greener Bangladesh. Experts recommend proper pricing of fossil fuel that will eventually help in phasing out such carbon emitting fuel to be replaced by renewables. With this aim in mind it would be good for the Government to depoliticize the energy price setting and let it be determined by market forces and regulated by the BERC devoid of political interference. Massive fiscal stimulus to fight the Covid-19 pandemic coupled with emerging supply constraints in specific areas due to structural problems have created an unprecedented global dilemma of rising inflationary pressures amidst inadequate economic recovery.

Bangladesh is also facing similar inflationary pressures added with the need to boost GDP growth. As such, the situation calls for deft economic management and political courage by managing its monetary and fiscal policies to avoid excess demand pressures and by depoliticizing the energy price setting. Shielding the economy from inflationary pressure by price controls and subsidies is not a viable policy option, especially if the government aims to stick to its long-term ambitions of achieving Upper Middle-Income Status (UMIC) by 2031 and High-Income Country (HIC) Status by 2041 by adopting a green growth strategy. There is no place for any fossil fuel subsidy in the green growth strategy. Moreover, public investments and incentive policies must be geared towards supporting the supply and using clean energy and green technology in agriculture, manufacturing, power, transport and construction.

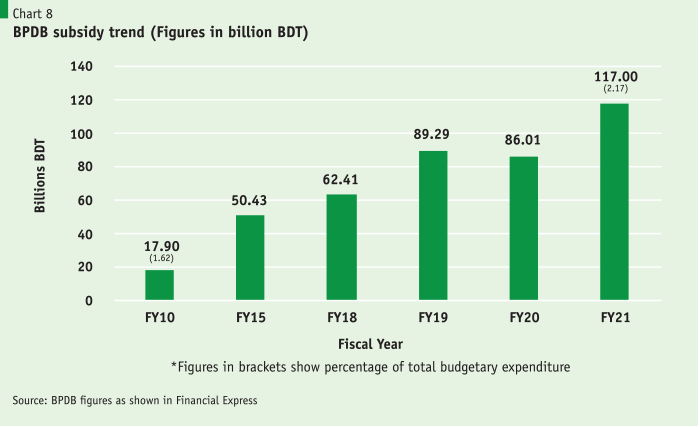

An aberration in the path towards phasing out fossil fuel in electricity generation is the sharp rise in subsidy to Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB). This is tantamount to incentivizing higher GHG emissions. With fuel-price spiral in the global market in the current fiscal year, state subsidy on power is expected to nearly double to BDT 200 billion. This might lead to an increase in subsidy requirement from power producers in FY2021-22. The power board received subsidy (to cover losses) worth around BDT117 billion in FY21, which was 35 per cent higher than previous FY’s BDT 86 billion. The BPDB sells electricity at Tk5.12 per unit while its average cost is around Tk 6.61 per unit (1kilowatt-hour) thus eventually requiring Tk 1.49 per unit as subsidy from Government to cover its losses (Fig.7).

The origin of the problem lay in massive power outages of a decade ago. During 2010, the government adopted a plan to mitigate the electricity crisis through installing dozens of oil-fired quick rental power plants. The subsidy requirement started soaring right after this policy came under commencement. The government allowed entrepreneurs duty-free import of furnace oil to run plants with a 9 per cent service charge along with import costs as an incentive. Currently the country’s furnace oil-fired power plants have the capacity to generate around 7,000MW electricity and the diesel plants have the capacity to generate around 1,000MW electricity – roughly 30% of current generation capacity. The challenge of phasing out fossil fuel-based electricity generation over the medium-term becomes that much more daunting.

Monetary Policy still on a tight rope

Since the outbreak of Covid19 pandemic monetary policy has been challenged on several fronts: fiscal stimulus and monetary accommodation, supply chain disruptions and rise in commodity prices worldwide, and recent pressures on the exchange rate from rising imports fueled by economic recovery. Monetary policy so far appears to be broadly in line with the objective of taming inflation and reversing growth slowdown by maintaining injection of adequate liquidity in the banking system. Year-on-Year growth of Broad Money (M2) increased slightly from 12.6% at the end of FY20 in June 2020 to 13.6% at the end of FY21 in June 2021, lower than the BB’s target of 15%, but still helped to support higher nominal growth in GDP. As per Bangladesh Bank’s latest Monetary Policy Statement for FY2021-22, the program is to continue with accommodative monetary policy to support targeted nominal GDP growth of 12%+. The pick up in business and trading activity during the first quarter of FY2022 gives hope for a strong recovery in the on-going fiscal year, unless that is interrupted by unforeseen developments in the pandemic scenario.

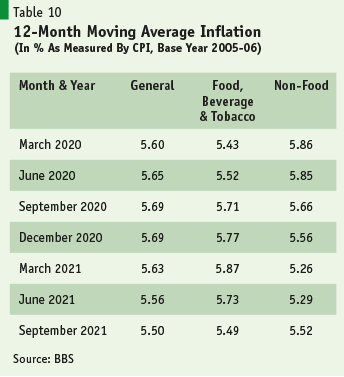

Inflation scenario. Except for a recent spike in non-food inflation both average and point-to-point inflation show moderating tendency since the start of FY2021 (Table 10 and Fig.8).

The uptick in recent non-food inflation is clearly the result of imported inflation as imports have risen sharply on account of strong economic recovery and the rise in oil and commodity prices in the world market.

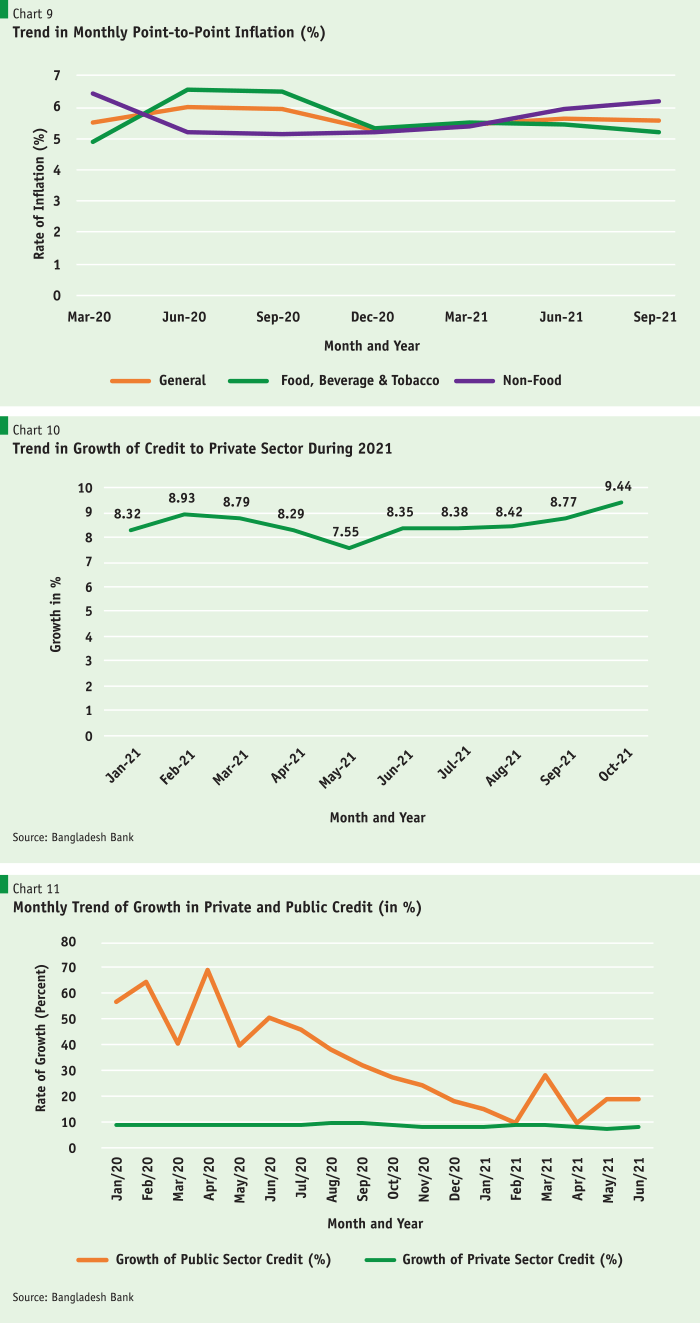

Credit growth. Another signal that economic recovery is under way can be found from the trends in private sector credit growth since the start of 2021. The earlier decline in the first half of 2021 has given way to a rising trend since May with a record 9.4% rise in October 2021 (Fig.9). Thanks to rising revenue collection by the NBR crowding out has been avoided as public sector demand on bank credit has fallen significantly from the lofty levels of 60-70% in the first half of 2020 (Fig.10).

As of this writing Covid19 pandemic and any future surges or emergence of more transmissible variant continues to present downside risks to the global economy even though advanced economies are experiencing strong growth for now. Bangladesh economy today is far too much integrated with the world economy to be immune to such developments. While monetary management thus far has been prudent and pro-growth at the same time, there could be challenges ahead in effectively pursuing the twin objectives of price stability and growth.

Epilogue….and the Way Forward

2020 and 2021 will live in history as the years of the Covid pandemic. Having learnt from two historical economic crises, the 1930s Great Depression and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the world today has plenty of ammunition in its armory to address such crises. A global crisis of this magnitude brings with it challenges and opportunities. The oft-quoted line of not letting a crisis go waste could not be more relevant. What this crisis has taught us is that we are not in it alone. If Covid persists anywhere the world community is not safe anywhere. So, it calls for global and multilateral cooperation to tame this crisis now and the ones that might emerge in future. Vaccine nationalism or vaccine divide between rich and poor nations does not help solve the problem at hand. Within Bangladesh, it calls for a whole-of-society approach to curb the pandemic impacts.

Globalization is not dead, writes the eminent journalist, Fareed Zakaria. Covid19 pandemic has set off deeper public-private cross-border cooperation in medical research, technological collaboration, and economic policy coordination, all thanks to the extraordinary degree of economic, social, and cultural integration that has taken place over the past 70 years since the second World War. The once floundering state of multilateralism could get a boost from the cooperative efforts to resuscitate the post-Covid19 global economy. The change in US leadership is already giving the signal that “multilateralism is back”. But make no mistake, fissures remain in the global body politic. Bangladesh is among the largest beneficiary of multilateralism and it has used its membership of multilateral institutions to substantially improve the welfare and conditions of its citizenry. More opportunities to do the same lie ahead.

Bangladesh, at 50, has taken a respectable place in the comity of nations. Bangladesh and Vietnam both emerged after fighting wars of independence. No one describes Vietnam’s economic achievements as the “Vietnam paradox”. Why should Bangladesh’s achievements be termed as a Bangladesh paradox? It is time to shed that narrative. Fighting for freedom and progress is in our DNA.

Notes: Research support was provided by PRI colleagues Sr. Economist Ashikur Rahman, Research Fellow Ziaul Ahsan, Economist Hasnat Alam, and Sr Research Associates Sabrina Shareef, Promito Musharraf Bhuiyan, Sumaiya Farah, Mahreen Mustafa, and Shafqat Shahadat Choudhury.