How trade policy evolution Steered course of Bangladesh development

By

Throughout history, trade has been the lifeline of nations and communities. But trade policy has never been a static phenomenon. Instead, it has followed an evolutionary pattern over time and across nations. Though speed and timing could have been better, policymakers in Bangladesh did well to draw from emerging ideas and global experiences with regard to trade policy stance, particularly ones that yielded the most rapid transformation of low-income economies.

Bangladesh celebrates the golden jubilee of independence this year (2021), and there is indeed much to celebrate. Analysts of all shades of opinion have hailed the quality of social and economic progress achieved by the country which was, at inception, derided as a “basket case” by none other than Henry Kissinger, the US secretary of state in 1972. Bangladesh emerged in the global map with a per capita income of under USD 100, at the bottom of the income pile, in the company of such nations as Chad, Rwanda, Burundi, and Nepal. Today, having crossed the per capita income threshold of USD 2500, with a GDP of about USD 400 billion, it ranks in the top 40 economies of the world in terms of GDP.

Over the past quarter century, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Bangladesh recorded the fastest and most stable rate of GDP growth among developing countries. The rates of moderate and extreme poverty also came down dramatically alongside GDP growth suggesting interlinkages between the drivers of the two positive phenomena. Any economy that consistently records 6-7% GDP growth per annum for two decades has to experience significant augmentation of income per capita accompanied with substantial reduction of poverty. The economy and society also undergo momentous transformation as a consequence. That is exactly what has happened in this country of about 170 million people.

What were the key drivers of this notable transformation? Of course, there were positive political and social developments that planted the pillars of stability and inclusiveness in the transformation process. The pivotal role of Government, supported by several of the world’s most lauded NGOs, was key to the steady social and economic progress achieved through the decades. Progress in human development was acclaimed by none other than Nobel Laureate economist, Amartya Sen, who has his roots in this part of the world. A leading columnist of the New York Times, Nicholas Kristof, went so far as to suggest that President Joe Biden draw lessons from Bangladesh on how to reduce poverty in USA. Multilateral agencies like the World Bank and IMF have repeatedly acknowledged, with the usual caveats, Bangladesh’s sound and prudent macroeconomic management as contributing to its sustained macroeconomic stability.

In my view, the general direction of economic policies was broadly consistent with the fundamental tenets of macroeconomic stability that laid the foundations for rapid growth and poverty reduction. To keen observers of the Bangladesh economic scene the trigger that unleashed the forces of rapid economic growth would have to be the radical change of direction in trade policy (complemented by market orientation and deregulation) during much of the 1990s decade. It is now possible to make the assessment that after first two decades of prevarication in trade policy Bangladesh was able to change course and get it right – at least partially so. In my assessment nowhere in the policy space was there such a radical change of direction as in the case of trade policy. Evidence shows that Bangladesh massively reaped the benefits of those changes in the subsequent decades prompting Arvind Subramaniam, a leading development economist, to describe Bangladesh as a “development paragon”. Such sobriquets have to be earned over decades of perseverance with economic and social policies while grappling with the scourge of abject poverty. In my view, switching gears in trade policy in the 1990s, from an inward-looking import-substituting policy to an outward-looking export-oriented trade policy was by far the game changer.

What follows is an attempt to put Bangladesh’s trade policy and development experience in historical perspective.

When the 18th century classical economists Smith-Ricardo-Mill1 formulated the fundamental propositions of trade theory, then demonstrated the gains from trade based on specialization according to comparative advantage, the predominant geopolitical current was governed by colonialism. The First Industrial Revolution further exacerbated the exploitative character of colonialism by treating colonies as markets for finished manufactures and suppliers of raw materials to the industries in Europe. The supporting trade strategy was mercantilism, which favored accumulating gold by exporting more and importing less, thus ensuring continuous trade surpluses, primarily at the expense of colonies. While wealth accumulated in the colonial empires, economic progress in the colonies was of little interest to the colonial masters.

For all their expose about the benefits of free and unfettered trade between nations, economic progress in the colonies was not on the radar of classical economists. “Economic development” per se as a strategy of raising incomes and improving the lives and livelihoods of deprived people around the globe was arguably a post-war phenomenon. The thirst for “development” and rapidly coming out of poverty among newly independent nations (former colonies) gave rise to alternative strategies of development. Trade policy then played a key role in the articulation of development strategies.

Trade strategies and development strategies are intricately correlated, particularly for developing economies aiming to raise income and rapidly grow out of poverty. Development entails structural transformation, from agriculture to industry, and within industry, a rising share of manufacturing. Of late, structural transformation has included the servicification of economies with rising share of modern technological services (such as IT) replacing informal service activities. That said, development literature since the 1960s has treated industrialization as being synonymous with development of underdeveloped economies. But the path to industrialization has required different versions of trade policy orientation, some of which yielded successful outcomes, others not so.

Trade strategies and development strategies are intricately correlated, particularly for developing economies aiming to raise income and rapidly grow out of poverty. Development entails structural transformation, from agriculture to industry, and within industry, a rising share of manufacturing. Of late, structural transformation has included the servicification of economies with rising share of modern technological services (such as IT) replacing informal service activities.

The lessons of the Depression years showed the criticality of international trade for global economic wellbeing. World leaders took note and founded the Bretton Woods system in the post-War period with multilateral regimes that would foster trade openness through reduction of tariffs and other restrictions on international trade. The world community reaped the benefits of that system for nearly 70 years as trade growth fueled income growth across continents. Yet, in the 1960s a different mantra of trade became the accepted wisdom – import substituting (IS) industrialization – for most developing economies rising out of colonial bondage. This development strategy involved restrictive trade policies that was adopted by many regions of the world including South Asia, with adverse consequences for economic progress in these regions. A different path to trade and development – trade openness and export-led growth — was carved out by East Asian countries. That remains the prevailing development paradigm till today with some variation that evolved over time.

Historical and cross-country evidence shows that the practice of trade policies falls into two broad categories: inward-looking import-substituting trade policy and outward-looking export-oriented trade policy. An alternative way of framing this categorization would be to relate them to the markets that are in focus – the domestic market for the former and the export or world market for the latter. The rationale for import substitution (IS) as a development strategy was based on its foreign exchange saving potential for economies that suffered from scarcity of foreign exchange and IS production was destined for the domestic market to replace competing imports.

Research evidence is plentiful showing that the IS strategy neither yielded rapid industrialization nor robust growth. On the other hand, there is overwhelming evidence confirming that economies embracing export-oriented strategies targeting external markets have grown rapidly. For many East Asian economies export orientation was so intensive and industrialization was so rapid that they turned from poor countries to become developed economies within the span of under 50 years. There is no such historical evidence of rapid development or structural transformation of economies using the IS trade strategy.

Back to Bangladesh. In the 1970s-decade, trade policy as an instrument of development never seems to have been on Bangladesh’s radar. The priority agenda was the focus on addressing massive poverty and fueling economic recovery of a devastated economy, largely through domestic-oriented policies supported with donor assistance. By default, the trade policy stance was a legacy of the past – where East Pakistan was turned into a captive market for West Pakistani financial and industrial corporates via high tariffs and import controls resulting in a virtually closed inward-looking import substituting economy. Starting with zero foreign exchange reserves to pay for much needed imports high tariffs and import controls were understandably the expedient approach to keep from falling into a balance of payments crisis. The notable industrial and trade policy innovation (indeed we can call it that) came with the special dispensation formulated for the readymade garment industry at the end of the decade. The innovation was the grant of duty-free importation of imported inputs and back-to-back LC facility to cover import costs to be paid from export proceeds. It was a novel scheme that created a level playing field for Bangladesh’s labor-intensive garment industry by providing world-priced inputs that were required. Taking advantage of this facility, Desh garments, set up by a visionary civil servant, collaborated with the Korean firm, Daewoo, to launch a 100% export-oriented enterprise to access western markets under the multi-fiber arrangement (MFA) that offered export quotas for Bangladesh. Thus, was born Bangladesh’s leading manufacturing sector that would exploit Bangladesh’s comparative advantage in labor-intensive production creating millions of jobs, particularly for women. The rest is history.

There were three notable developments in the trade policy arena during the 1980s. First, there was widespread disenchantment over import as a strategy of development because there was growing evidence that this approach neither generated competitive industrialization nor fueled growth. On the other hand, protectionism tended to perpetuate itself leaving numerous inefficient firms in its wake as “infant” industries failed to become competitive and needed higher protection over time to survive. Second, departing from the import substitution regime a new development paradigm– export-led growth – had emerged out of the tremendous export-led growth success of several East Asian economies (described by the World Bank (WB) as the East Asian Miracle) in the 1960s and 1970s. By the 1980s this new paradigm had got a firm foothold in the development discourse. Third, there was the Washington Consensus (a set of free-market economic policies that emphasized inter alia trade liberalization and was promoted by multilateral institutions such as the IMF and WB) that gained currency among development institutions and most development practitioners.

Inexplicably, these significant developments in policy sphere got little or no attention from policymakers in Bangladesh. Thus, as far as trade policy developments in Bangladesh are concerned, 1980s was a lost decade. There was little traction in mainstreaming trade policy as an instrument for development as the government took no initiative to bring trade policies into the development discourse. When trade related actions were taken at the prompting of multilateral institutions it tended to be episodic (e.g., tied to some World Bank loan) and limited to tariff liberalization for specific imports or sectors, without a wholistic approach towards overall extent of trade openness or measures to augment competitiveness. The only notable development was the tariff liberalization for imports of agricultural inputs that complemented the deregulation in the domestic agricultural markets – for seeds, fertilizer, machinery and implements. The general trade policy stance did little to improve the balance of payments situation nor fueled GDP growth which was anemic throughout the decade culminating in the BOP crisis of 1990. What could be levelled as a missed opportunity was the lack of an effort to adopt the new paradigm of export-led development, a paradigm that emerged in our East Asian neighborhood and should have caught the attention of our policymakers right away…. but did not. Thankfully, that changed in the subsequent decade.

The 1990s was truly the golden period of trade policy developments when you consider the whole gamut of radical changes in the trade policy regime that were launched at the start of the decade. At the close of the 1980s the economy was literally in shambles. GDP growth was anemic, foreign exchange reserves had reached rock bottom, and financing of the BOP deficit was at a dead end. The confluence of an economic and political crisis (collapse of Ershad regime and onset of democracy) paved the way for radical reforms. The economic mess left by the departing regime had to be cleared first to restore the economy’s potential for growth and poverty reduction. The WB-IMF stepped in to save the situation with structural adjustment loans and BOP support on the back of wide-ranging trade policy reforms. Much needed structural reforms were introduced that included measures for restoring internal macroeconomic stability through fiscal conservatism, market orientation and deregulation of investment, privatization of state-owned enterprises, a la Washington Consensus. Compared to the previous 20 years, the trade policy changes undertaken could be termed radical indeed and included (a) sharp reduction and rationalization of tariffs, (b) significant import liberalization through removal of bans, quantitative restrictions (QRs) and import licensing (end of license raj), (c) move from fixed to flexible exchange rates, and (d) limited convertibility of the current account. This time trade liberalization during the 1990s was deep and transformative. In 2001, a seminal World Bank study on the impact of trade liberalization on growth and poverty (David Dollar and Art Kraay, Trade, Growth and Poverty, published in The Economic Journal) listed Bangladesh among the “globalizers” of the developing world, confirming through empirical evidence that these globalizers were experiencing rapid growth in incomes and declines in poverty.

Much needed structural reforms were introduced that included measures for restoring internal macroeconomic stability through fiscal conservatism, market orientation and deregulation of investment, privatization of state-owned enterprises, a la Washington Consensus. Compared to the previous 20 years, the trade policy changes undertaken could be termed radical indeed and included (a) sharp reduction and rationalization of tariffs, (b) significant import liberalization through removal of bans, quantitative restrictions (QRs) and import licensing (end of license raj), (c) move from fixed to flexible exchange rates, and (d) limited convertibility of the current account.

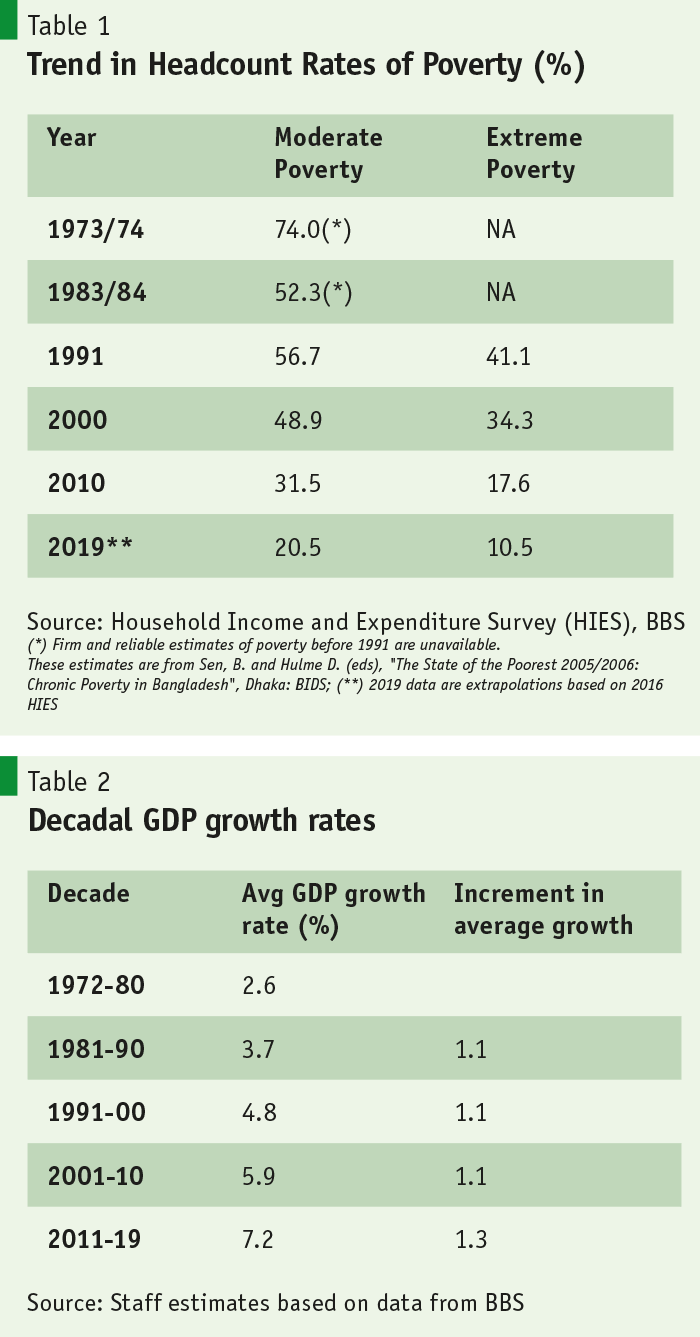

In hindsight we can argue that the WB findings signaled the dawn of a new era of trade openness that fueled rapid growth and poverty reduction in Bangladesh with the advent of the 21st century. The strategy of export-led growth built on the back of trade liberalizing policies had finally taken hold in the policy space. The liberalizing reforms of the 1990s, albeit incomplete, generated enough momentum to stimulate export-oriented manufacturing growth, job creation, and poverty reduction for the next two decades, and the momentum continues to this day. Average decadal GDP growth began rising by over one percentage point every decade, 4.8% in FY91-00, 5.9% in FY2001-10, and 7.2% in FY2011-19. The moderate poverty rate which was 57% in 1990 was nearly halved by 2010 (31.5%), and is estimated to be around 20% in 2019 – highly effective sign of inclusive growth (Table 1-2). Multilateral agencies like the World Bank have recognized Bangladesh’s remarkable progress in poverty reduction over the decades. Like everywhere else, the onslaught of the Covid-19 pandemic has clearly disrupted the steady path of economic progress as well as poverty reduction during 2020-2021, but there are signs that a robust global output and trade recovery is underway, and Bangladesh hopes to reap the benefits of that recovery through a rejuvenation of its export strategy in order to return to its pre-pandemic growth path.

Sadly, the advent of the 21st century saw the emergence of some degree of political instability during which deepening of trade policy reforms did not appear feasible. Unlike the 1990s, the first decade of the 21st century saw a slowdown in tariff reduction or other trade reforms which were episodic at best. The reform highlight of this decade was the move from flexible to floating exchange rate (managed float actually) launched by Bangladesh Bank in 2004 along with a final elimination by Ministry of Commerce of all bans/QRs on imports for protection reasons. The latter was done through a modest scheme of tariffication of the last remaining QRs on textile imports. One para-tariff, IDRC (infrastructure development surcharge) was eliminated and absorbed with custom duties (CD). But no sooner was this chapter closed, another para-tariff, regulatory duty (RD) of 3% across the board emerged in FY2010. It is fair to say that with that closed the chapter on tariff reforms. RD, which by law has to be renewed every year, has gained a life of its own and it looks unlikely to be abandoned any time soon. Meanwhile, Supplementary duties (SD), a para-tariff that was introduced under the VAT and Supplementary Duties Act of 1991, became even more pronounced as an instrument of protection as, according to PRI research, 95% of all SD impositions were intended to protect domestic industries. As confirmed by the WTO in its 2019 Trade Policy Review, tariffs and para-tariffs are now the principal instruments of trade policy in Bangladesh.

Trade economists have long argued that export performance and tariff protection are not mutually exclusive. Tariffs on import substitute production are indirect subsidies that undermine support to exports and create anti-export bias. Having carved out a virtually free trade regime for the 100% export-oriented RMG sector, by ensuring world-priced inputs through the Special Bonded Warehouse System, there was too much internal resistance to the replication of this regime for the non-RMG exports. A trade economist would argue that the protectionist lobbies appeared insurmountable to create an RMG-like regime for some 1400 (HS-6-digit) non-RMG export products that Bangladesh exported in 2019. Consequently, despite evidence of potential comparative advantage, non-RMG exports got no traction, continuing to remain in the shadows of RMG exports that continues to dominate the export basket (84% of exports). The evidence is strong that these non-RMG exports which are not 100% export-oriented — in the sense that its producers cater to the domestic as well export markets — find profitability from the highly protected domestic markets relatively higher. Thus, export diversification remains stalled on the anvil of anti-export bias of the protection regime. With all its faults our claim to export success is built on the record of the readymade garment industry.

The sooner we can come out of our antiquated tariff regime and make our tariff structure reflective of a dynamic export-oriented economy the better our chance of diversifying our exports and fueling post-Covid economic recovery with a bustling diversified export-driven manufacturing sector that creates jobs and income to win the war on poverty. This is exactly the strategy laid out in the Government’s 8th Five Year Plan (FY21-25). For the first time in decades, we see promising developments in relevant economic ministries for rationalization and modernization of Bangladesh’s tariff structure to bring it in tune with the dynamics of competitive global trade. This is clearly a welcome development.

One critical point that needs mention is that export-oriented policies in practice have most often been accompanied by appropriate exchange rate management that kept the exchange rate from being over-valued, a phenomenon that clearly retards exports. There is no denying that the exchange rate is a pivotal policy variable in the conduct of trade policy. Research evidence shows that countries that relied on export push for rapid growth also ensured long periods of depreciated exchange rate . What is critical for successful export push is to avoid any over-valuation of the exchange rate. This was the mistake made by economies that took to import substitution as their trade policy orientation. It was common for them to resort to extreme currency over-valuation combined with quantitative restrictions on imports resulting in the equivalent of prohibitive tariff protection. Bangladesh was no exception, up until 1990. Overvaluation of the currency stifles export growth, reduces foreign exchange earnings leading to further restriction on imports often in highly irrational and indiscriminate ways. Governance of IS strategies has been the subject of research in many developing economies.

One critical point that needs mention is that export-oriented policies in practice have most often been accompanied by appropriate exchange rate management that kept the exchange rate from being over-valued, a phenomenon that clearly retards exports. There is no denying that the exchange rate is a pivotal policy variable in the conduct of trade policy. Research evidence shows that countries that relied on export push for rapid growth also ensured long periods of depreciated exchange rate .2

Finally, the case for export-oriented development came out strongly in the report of the Growth Commission set up by the UN in the early 21st century and led by Nobel Laureate Michael Spence. One important conclusion that came out of that research was that unlike in the past centuries, developing economies could now grow at rates of 7,8,9, or 10, by leveraging demand in the global marketplace, something the domestic market cannot offer. Trade economists like Anne Kruger argued strongly that the domestic market of most developing economies was too small to offer the kind of scale economies that the global economy can provide. The global market is just too big so that no single country can affect world prices. That means, basically, that you can export and grow as fast as you can invest, provided you have some competitive edge. East Asian countries, eager to develop rapidly, realized this early on in the 20th century. And East Asian economies continue to show the world new variants of export-led growth in the 21st century.

While theories about the gains from trade originated from the minds of thinkers and thought leaders in Europe and North America, the practice of leveraging international trade to transform poor backward economies into prosperous and developed economies within a time frame of 50 years originated from the leaders and governments of East Asian countries. East Asia led the way.

After the 2020 annus horribilis, a terrible year, Bangladesh economy finds itself at a crossroads. The challenge to revive exports and grow at an average of 8% per annum over the next 3-5 years has never been more daunting as graduation from LDC status in 2026 beckons – with the prospect of losing many of the International Support Measures (ISM) that gave a boost to our exports. It would be a fair assessment to suggest that Bangladesh energetically launched first generation trade reforms in the 1990s and is still reaping the benefits of those reforms in terms of export, growth and poverty impacts. But tariff reforms, one critical ingredient of trade policy, still remain largely unfinished with some ossification evident in recent times. Can the economy achieve its medium-term goals without modernizing its tariff structure? As I have argued in many fora and writings, the current tariff regime is a major stumbling block to the realization of export diversification – a priority development agenda of the Government.

As the nation addresses trade facilitation as part of second-generation trade reforms, completing the unfinished agenda of trade and tariff reforms begun in the 1990s and taking them to their natural conclusion should be a national imperative that will yield rich dividends on way to Bangladesh becoming an Upper Middle-Income Country by 2031. Meanwhile, thanks to our young generation of RMG entrepreneurs and their backward linkage partners in the textiles and accessories industries, Bangladesh recently gained the epithet of “The New Asian Tiger” from the international business media (e.g. Bloomberg News), a tacit comparison to the East Asian Tiger Economies (S. Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore) of the 1960-70s. But all this praise stems from the enormous success in one export product group – RMG. If one looks at the export performance of non-RMG products for the past 25 years, there is nothing to write home about. Imagine where Bangladesh export performance would be without the inherent anti-export bias of the high and persistent tariff protection in the non-garment manufacturing sector.

In the year 2021, the 50th anniversary of Bangladesh’s independence and the centenary year of Bangabandhu’s birth, the Bangladesh economy is recognized for its robust growth performance in the past 25 years, solid record of poverty reduction, and above peer-level indicators in health, education and social outcomes, to earn the sobriquet of a “development paragon”. Nevertheless, the economy stands at a historical inflexion point with a long unfinished agenda. It is the ideal turning point in the country’s history to launch a major reform initiative in the realm of trade policy to instill the kind of growth momentum that was experienced by economies in East Asia over the past 70 years. The momentum is clearly evident. It has the potential to grow at sustainable rates of 7%+. But opportunities opening up in the global marketplace of the 21st century must be seized through aggressive trade and supportive economic reforms, like the East Asian economies did and are still doing, if Bangladesh is to live up to the reputation of resilience and dynamism that it has earned so far, defying the geopolitical doomsayers once and for all. Getting its trade policy right for the 21st century, just as it did for the 1990s, has become a national imperative.

Notes:

1 Refers to 18-19th century classical economists Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, who first articulated and formulated the theory of comparative advantage in trade.

2 East Asian economies that emphasized export promotion also kept their exchange rates depreciated. Most recent example is that of China, which was subject to regular accusation from US policymakers who frequently accused China of currency manipulation as a means to make their products appear more competitive.