FY 23 Budget Fiscal Policy and Macroeconomic Management

By

Recent Macroeconomic Developments

Macroeconomic stability has been a hallmark of Bangladesh development strategy. This has served the country well by providing a solid enabling environment for the private sector. Relatively low inflation (long term average rate of 6.1% over the 1990-2021 periods) has also been helpful in preserving the gains in nominal income for the poor and the fixed income groups. Periodic episodes of imbalances were quickly reversed through sound macroeconomic management involving relevant reforms.

In recent months, the combination of Covid-19 global supply disruptions and the food-fuel supply crisis related to the Ukraine War have created serious global inflationary pressures. Over the past 12 months, the inflation rate has increased from 4.2% to 8.3% in the USA, 1.5% to 9% in the UK, 2.0% to 7.4% in Germany, 3.4% to 6.8% in Canada, 4.2% to 7.8% in India, 5.5% to 33.8% in Sri Lanka, and 11.1% to 13.4% in Pakistan.

Bangladesh being an open economy is no exception. Although official CPI data show a much lower inflationary pressure (rising from 5.6% to 6.3%), this has met with skepticism in many quarters given the depth of global inflation. More importantly, individual commodity prices relating to food items show substantial increases over a 12- month period (e.g., Dhaka retail prices suggest the following increases: rice 15%; atta 30%; cooking oil 43%, sugar 29% and lentil 15%) that are hurting consumers at large but especially the poor and the fixed income group. Additionally, the import bill has surged while the flow of remittances has slowed. This has created huge excess demand for foreign exchange at the official rate, thereby exerting substantial pressure on the exchange rate in the open market.

Appropriate Macroeconomic Management

What are the good and sustainable policy options? The macroeconomic imbalances emerge from three sources: inflationary pressure; the balance of payments pressure and the fiscal pressure. Addressing these issues require the use of at least three policy instruments that best relate to each of these areas: use of monetary policy instruments to ease inflationary pressure; exchange rate policy to ease the balance of payments pressure; and tax/ expenditure policy measures to ease the budgetary pressure. Their combined use as a coordinated set of policy actions can help avoid the bluntness of any single instrument and reinforce the effectiveness of each of the policy reforms.

Monetary Policy

Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman had famously stated that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon. This is a truism because without monetary impulse, changes in individual prices cannot create sustained inflation. The debate about this extreme monetarism concerns the worry that using monetary policy instrument only can be blunt and hurt economic growth. For temporary inflationary pressure, one can ignore the need to use monetary policy. But for prolonged period of inflation, as presently, it is too risky to avoid the use of monetary policy instrument. Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors across many countries including USA, UK, Canada, Australia, and India have recognised this challenge and have raised interest rates to reduce aggregate demand. The European Central Bank (ECB) is also poised to hike interest rate in July. The increases are being calibrated to have the desired effect in lowering inflation while moderating the adverse effect on economic growth.

For Bangladesh, the monetary policy challenge is to modify what has come to be popularly known as the “6/9” policy, whereby the deposit rate cannot exceed 6% and the lending rate cannot exceed 9%. This played a positive role during the Covid-19 years (2020 and 2021) and along with other supportive policies helped the post-Covid economic recovery. With sustained inflationary and balance of payments (bop) pressures, the policy should be modified to let interest rate be market determined along with increases in the policy rate managed by the Bangladesh Bank. Without a change in the 6/9 policy, the increase in the policy rate will be largely futile. Creating a secondary market for T-bills will help increase the effectiveness of monetary policy. The policy rate, reserve requirements and open market T-bill operations can all be used to moderate increases in the interest rates.

Exchange Rate Management

Bangladesh Bank (BB) is well aware that the Taka has been appreciating in real terms steadily against major currencies like the US Dollar and the Euro, and also against the basket of currencies used by BB to calculate the real effective exchange rate (REER). The REER trend shows that the value of BDT appreciated in real terms by 71% between FY2011 and FY2020. This was clearly unsustainable, as has become evident now. So, the depreciation of the BDT was long overdue. Following the failure of some vain attempts to control the slide in the exchange rate in the open market, on June 01 the BB freed up the exchange rate and letting it be market determined. The freeing up the exchange rate was a smart move. A more flexible management of the exchange rate than in the past will allow the exchange rate to play its role in export growth and reduction of import. Along with flexibility of the exchange rate, monetary and fiscal policies should be used to moderate the demand pressure on imports to provide some stability to the downward movement of the exchange rate.

Fiscal Policy

The new national Budget for FY2023, effective from July 01, gives an opportunity for the government to accelerate its stabilising policies. Bangladesh has made solid progress with economic recovery from the initial downturn induced by the covid shock in FY2021. While the government is keen to push the recovery further using the new FY2023 Budget, this eagerness must be tempered with the reality that the macroeconomy must be stabilised first. For the immediate short term, this is the topmost priority, and the new Budget must acknowledge that and build its fiscal policy responses along that task.

The new national Budget for FY2023, effective from July 01, gives an opportunity for the government to accelerate its stabilising policies. Bangladesh has made solid progress with economic recovery from the initial downturn induced by the covid shock in FY2021. While the government is keen to push the recovery further using the new FY2023 Budget, this eagerness must be tempered with the reality that the macroeconomy must be stabilised first.

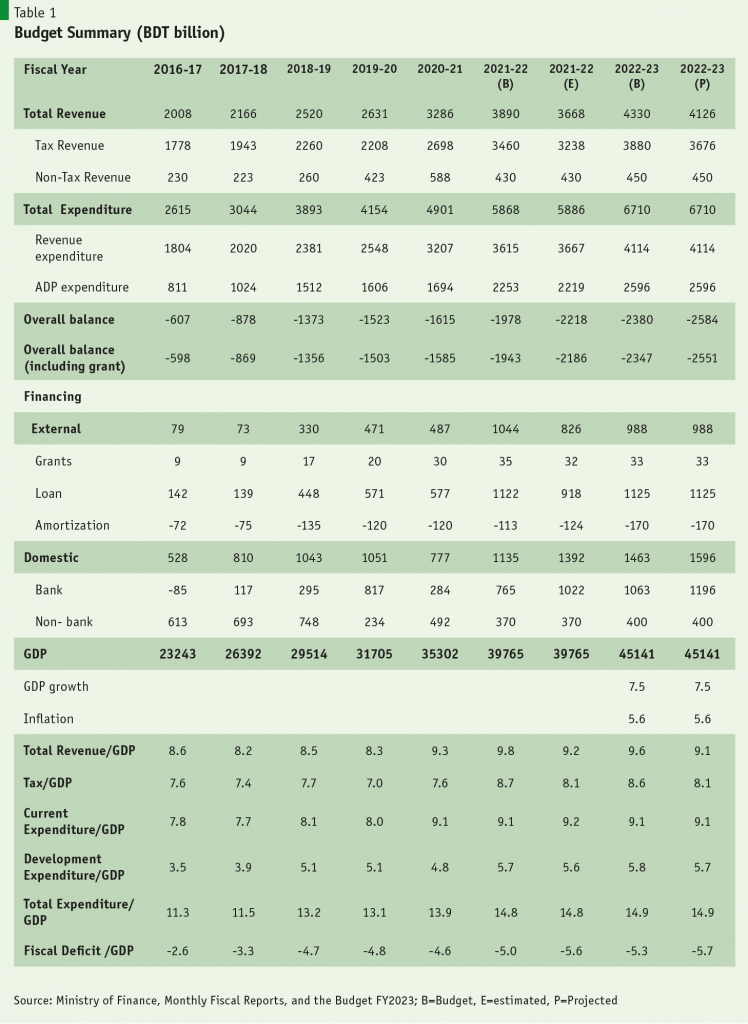

Unfortunately, the initial Budget proposal presented to the Parliament on June 06 gives a mixed signal (Table 1). It recognises the need for economic stability but builds the Budget around a higher GDP growth target than last year. Importantly, the announcement for changing the fixed 6/9 interest rate is missing from the Budget speech. Public expenditure is projected to increase by 12% in real terms over the revised expenditure for FY2022, largely fuelled by the burgeoning subsidy bill, and the fiscal deficit is projected at around 5.3% of GDP. On the surface, these spending and deficit targets do not appear excessive, but in the current situation of high inflation and import pressure on the exchange rate, a more prudent fiscal policy management would be appropriate.

Tax reforms

More generally, the fiscal policy pressure on economic management has been mounting for a while due to the slow growth in tax revenues. The Bangladesh tax/GDP ratio is one of the lowest in the developing world and has basically stagnated at 7-8% of GDP over the past 6 years (Table 1). Much has been written and known to the government about the need to modernise the Bangladesh tax structure with a view to increasing, tax efficiency, tax buoyancy and revenue growth. Unfortunately, no significant tax reforms has happened for over a decade. Without strong political signal, this will not be possible.

As in the past budgets, the FY2023 Budget does not have any coherent thinking or strategic approach to tax reforms. The Budget tinkers with a range of small tax measures that are a mixed bag of different elements, including supplementary tax increases for a large number of imported goods, some reductions in corporate income tax, some tax incentives and some removal of exemptions, and a few administrative measures to increase tax coverage. It is near impossible to systematically assess the overall revenue implications of these proposals. Regarding implication for resource allocation, it paints a mixed picture with a positive incentive for non-garment exports by extending them the same tax incentives as for RMG, but a further increase in the anti-export bias of trade taxes as reflected in increase in the average nominal protection owing to the new supplementary duties.

The long overdue reform of the personal income tax system, which is the key to improving tax buoyancy and tax collection, has not happened. These include measures like bringing all income under the personal tax net irrespective of source, simplifying tax filing requirements by eliminating the income-expenditure balancing that is an instrument of tax harassment and corruption, moving to a truly self-assessment tax filing system with limited, focused, and productive audits, removing discretionary approach to tax filing by removing the interface between tax filers and tax collectors, simplifying tax filing through online submissions and payments. The VAT Law of 2012 is still not properly implemented. Trade taxes have not been streamlined to lower trade protection. The property tax reform, which is essential to strengthen the revenue base of the local government institutions, has not happened.

Against the backdrop of the above, the most likely revenue outcome will be status quo. Thus, the total revenue (tax and non- tax) amounted to 9.3 % of GDP in FY2021 (7.6% tax to GDP ratio and 1.7% non-tax revenue to GDP ratio). The rapid increase in the import bill has facilitated a strong growth in tax revenue in the first nine months of FY2022, amounting to 19%. So, assuming a 20% increase for the full fiscal year, tax revenues is estimated to amount to BDT 3,238 billion, or 8.1% of GDP, for the full fiscal year. This is a welcome increase, but the revenue growth rate is not sustainable as it is linked more to the import base than the GDP base. So, in FY 2023, tax to GDP ratio will likely stay at 8.1% of GDP, rather than reach the Budget target of 8.6% of GDP. This implies that tax revenues will likely grow to BDT 3676 billion (14% increase) as against the budget target of BDT 3,880 billion (20% increase). Although this is a modest shortfall (BDT 204 billion) as compared with the past, nevertheless without expenditure cuts this will increase the budget deficit to 5.7% of GDP.

Non-tax revenues in FY2022 declined to 1.1% of GDP, lower than what was achieved in FY2021 because of the one -time surrender of surpluses of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in FY2021. No reforms to improve the financial performance of SOEs were included in the FY2022 Budget. The contribution of non-tax revenue is budgeted to fall further to only 1% of GDP in FY2023 since again no reforms of SOEs are included. So, total revenue will likely amount to 9.1% of GDP, slightly lower than estimated for FY2022. This absence of increase in fiscal revenues as a share of GDP will severely handicap the FY2023 Budget’s ability to support either stabilisation or GDP growth.

Expenditure reforms

The main stabilisation responses in the Budget is to lower the import duty for a few sensitive items and the proposal to use subsidy judiciously to reduce the inflationary impact of global energy and fertiliser price increases. The concern here is the fiscal sustainability of this expansive subsidy policy. Fiscal subsidies are estimated to reach BDT 625 billion in FY2022 (1.6% of GDP) and surge to BDT 850 billion (1.9% of GDP) in FY2023 if no energy and fertiliser price increases are allowed. In this scenario, subsidy alone will eat up 21% of total revenues. Given other fixed spending items: wages and salaries (2% of GDP), pension (0.8% of GDP), supply and maintenance (1% of GDP), transfers to local governments and SOEs (1.4% of GDP) and interest cost of debt servicing (2% of GDP), there will be very little fiscal space for spending on social protection and high priority development spending on health, education, and infrastructure. The Budget recognises this handicap and proposes a fiscal deficit of 5.3% of GDP to fund other critical spending. Even this level of fiscal deficit will be barely adequate to finance needed spending on health, education, infrastructure, and social protection. Additionally, the projected revenue shortfall will further create expenditure difficulties, unless the government increases the fiscal deficit, which will hurt the adjustment efforts.

The main stabilisation responses in the Budget is to lower the import duty for a few sensitive items and the proposal to use subsidy judiciously to reduce the inflationary impact of global energy and fertiliser price increases. The concern here is the fiscal sustainability of this expansive subsidy policy. Fiscal subsidies are estimated to reach BDT 625 billion in FY2022 (1.6% of GDP) and surge to BDT 850 billion (1.9% of GDP) in FY2023 if no energy and fertiliser price increases are allowed.

The Way Forward

Bangladesh is facing macroeconomic stability challenges that it needs to address swiftly. At the same time, it faces two longer term development challenges. First, the GDP growth path of the 2041 Perspective Plan (PP2041) was derailed by Covid-19 and the government is keen to restore that path. Second, income inequality in Bangladesh has grown substantially and the adverse effects of Covid-19 plus the prevailing high inflation will further aggravate the income inequality problem. So, Bangladesh needs to address this social problem decisively and comprehensively. How could fiscal policy be used to reconcile these three objectives?

Restoring macroeconomic stability: Needless to say, at the top of the fiscal policy agenda is the need to restore macroeconomic stability. This is the foremost economic challenge facing the FY2023 budget. A combination of flexible management of the exchange rate, some monetary tightening and a judicious use of tax and expenditure measures are required to support the adjustment agenda. Bangladesh has taken the first step to make the exchange rate flexible, but it has not removed the 6/9 interest rate policy, which makes monetary policy ineffective in increasing the market interest rate that is required to lower the demand for credit. Regarding fiscal policy, it has failed to take adequate tax measures necessary to lower the fiscal deficit to support the adjustment. Indeed, the budgeted fiscal deficit of 5.3% of GDP is high in an environment where the deficit should be cut to lower aggregate demand. Furthermore, as noted, this could increase even further because the tax target will likely be missed.

On the expenditure front, the attempt to lower inflation by trying to insulate the international price increases in energy and fertiliser from affecting domestic prices has basically taken away the flexibility to protect the income of the poor through higher increases in health, education, and social protection. In the absence of tax measures, a better policy would be to lower the fiscal deficit to below 5% of GDP and allow stepwise increases in the prices of energy products and fertiliser to keep the subsidy bill for these items under control. So, instead of providing 1.9% of GDP as budget subsidy, this should be restricted to 1% of GDP and the balance should be reallocated to reduce fiscal deficit (0.5% of GDP) and provide income transfers to the poor (0.4% of GDP).

Restoring the growth momentum: Regarding restoring the growth momentum, it is a medium-to-long-term development agenda that must be steadily pursued. In the near term, there might be a trade off between growth and stability. Restoring stability requires cutback in demand that will likely have a dampening effect on GDP growth. This is inevitable and it is best to recognise this upfront and moderate the GDP growth target somewhat. A 6-6.5% GDP growth target for FY2023 is very healthy and is by no means a signal of defeat or retreat. But if macroeconomic stability is not restored, the balance of payments deficit and inflation could hurt growth over the medium-to-longer term that can be far more costly.

Since inflation hurts the poor and the low-income group relatively more than the rich, an important and positive fiscal policy measure would be to put priority to spending on health, education, and social protection to support the income of the poor and the vulnerable. Acceleration of income-transfer programs to the poor and vulnerable will be a strong policy move to protect the poor from the adverse effects of inflation. So, instead of subsidising energy for all consumers, a combination of energy price increase and re-channeling the saved resources as income transfers to the poor and vulnerable through the social protection system is a better policy option. In health, a most urgent reform is the introduction of universal health care through government-funded health insurance schemes for the poor.

The medium-term growth agenda requires substantial reforms outside fiscal policy. Within fiscal policy, the implementation of the 8FYP Fiscal Policy Framework is absolutely critical to restore the growth momentum to the PP2041 growth path. Among other fiscal reforms, it calls for tax to GDP ratio to grow from 8% of GDP in FY2020 to 12% of GDP by FY2025. Bangladesh is way, way behind on this. This ought to be a top policy priority at the highest political level. An expert Tax Reform Commission might be helpful to develop sound tax reform program that is not diluted by vested interests.

Learning from the experience of Western Europe, Bangladesh must introduce a redistributive fiscal policy. In essence, this calls for a substantial increase in the tax revenue base through the deployment of a progressive personal income tax system and using a part of this revenue to finance social expenditures in health, education and social protection focused on the poor, the low-income group, and the vulnerable population.

Reducing income inequality: This is a medium to long-term agenda. Learning from the experience of Western Europe, Bangladesh must introduce a redistributive fiscal policy. In essence, this calls for a substantial increase in the tax revenue base through the deployment of a progressive personal income tax system and using a part of this revenue to finance social expenditures in health, education and social protection focused on the poor, the low-income group, and the vulnerable population. The redistributive fiscal policy reform was incorporated in the 8FYP. Unfortunately, this has not been implemented so far. The earlier this reform is implemented, the better the prospects for improved income distribution.