Building Resilience under Macroeconomic Strain State of the Bangladesh Economy 2022

By

Post-pandemic recovery stifled

After the catastrophic year of 2020, the year 2022 has been another annus horribilis – terrible year for the world economy as well as for Bangladesh. Sadly, as the Bangladesh economy was climbing out of the 2020 Covid-19 debacle, another ‘Black Swan’ event – the Russia-Ukraine war – cast a deep shadow on the prospects of robust growth as the economy faced severe macroeconomic strain arising from global developments. Not just Bangladesh, the global economy also dealt a massive blow from a war between two countries on which a substantial part of the world community relied for critical supplies of food (Ukraine) and fuel (Russia). As the war continues unabated, developing economies around the world are reeling under the strains of balance of payments and debt crisis. According to reports, some 60 developing countries have been desperately knocking on the doors of IMF for bailouts. Not Bangladesh.

Ever since Bangladesh authorities placed a request to IMF for a USD 4.5 billion funding –under various facilities, news reports have not been very palatable leading the IMF Dhaka office to come out and make the unusual clarification that Bangladesh’s request was merely a preemptive measure only to move to a comfort zone of reserve levels. Indeed, a few months ago (April 2022) IMF in its Article IV report, which undertook a debt sustainability analysis jointly with the World Bank (a standard practice), described Bangladesh’s debt situation as comfortable. Of course, global market developments of the last quarter of FY2022, which resulted in a 35% surge in our import bill, resulted in a record current account deficit of 4% of GDP at the close of June 2022. Short of disgorging copious amounts of foreign exchange from its reserves, Bangladesh Bank had no option but to let the exchange rate float (from its BDT 86/USD fix) until it had depreciated by about 20%, roughly the degree to which the US dollar, the primary means of Bangladesh’s international payments, had appreciated over the past year. A depreciation of the exchange rate is one way of restoring balance by curbing imports and incentivizing exports and remittances. The balance of payments (BOP), somewhat strained at the edges, is still under close watch by the central bank and all efforts are on to restore balance and sustainability to this critical macroeconomic indicator. IMF’s commitment (without much fanfare about conditionalities) of USD 4.5 billion, to be disbursed in 6 tranches over the next three years, will surely stabilise the situation. More budget support funds are expected from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank and few other bilateral and multilateral institutions. More than many other developing economies, Bangladesh deserves multilateral support as it has been a responsible debtor for the past 50 years. Such support should restore stability to the BOP and ease the pressure on the exchange rate over the medium-term.

The year 2022 has been rocky, to say the least. The first half of FY2022 (ended December 2021) saw robust recovery from the Covid pandemic setback. That cart was turned upside down by the events following the launch of the Russia-Ukraine war, with the year ending in a yawning current account deficit, high but imported domestic inflation, depleting foreign exchange reserves, and unprecedented exchange rate depreciation. As the first half of FY2023 comes to a close, the economy is still trying to cope with the emerging challenges that required invoking austerity measures in public and private spending besides putting the brakes on imports through various administrative curbs in addition to the restraining impact of exchange rate depreciation. The initial burst of exports and remittances at the start of FY2023 seems to have petered out as the calendar year 2022 closes. The second half of FY2023 is expected to experience measured economic expansion while restoring external balance. Much work remains to be seen in the effective management of the exchange rate as the authorities try to bring stability in the exchange regime. That is critical for macroeconomic stability, both external and internal.

Mellowing global outlook dampens Bangladesh prospects but….

The world economy has been rattled by the war in Eastern Europe and its aftermath. The situation is still evolving. Tectonic shifts could take place in the geopolitical order that will surely have ramifications for the post-WWII geoeconomic order. Post-1990 peace dividend is all but over. Leaders of the G20 countries who met in Bali last week have work on their hands to build a new globalization regime. How inclusive or how fragmented that will be is up to the leaders of these economies. Remarkably, China and Russia are both members of this group apart from the developed West and emerging market economies like Brazil, South Africa, India and Indonesia. Strong headwinds have emerged in the global economy with the idea of decoupling from China promoted by several western nations. While the recently concluded WTO MC12 reiterated the message of inclusive rules-based trade, ideas of ‘re-shoring’, ‘friend-shoring’, and ‘strategic autonomy’ have been gaining ground in the western world, which has historically provided leadership to the growth of world trade for more than 65 years since 1945.

In this background, the recently concluded G20 meeting in Bali, Indonesia, produced all the right commitments, like cooperatively addressing the challenge of climate change and mobilizing adequate resources to fund adaptation and mitigation. More important was the acknowledgement that the Russia-Ukraine war was causing immense human suffering and exacerbating existing fragilities in the global economy – constraining growth, increasing inflation, disrupting supply chains, heightening energy and food insecurity, and elevating financial stability risks. Though some members had diverse views on some commitments, the theme – Recover Together, Recover Stronger – was generally advanced as the principal agenda of the group which showed deep concerns about the challenges to global food security exacerbated by the rising tensions and conflicts. Other commitments included endorsing the need to protect macroeconomic and financial stability for a strong, inclusive and resilient global recovery through coordinated actions. More important than what they say, what the G20 members now do is the critical part for developing economies like Bangladesh.

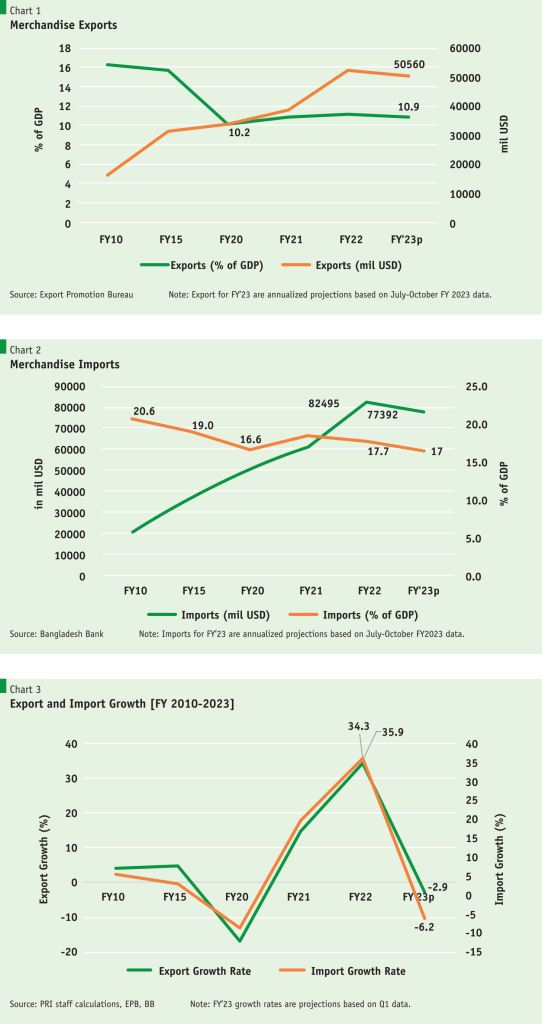

Thanks to its rising trade volume, which reached nearly USD 150 billion in FY2022 compared to only USD 12 billion in 2000, Bangladesh is now far more integrated with the world economy. What happens in G20 economies is key to Bangladesh’s export prospects, which is why we ought to follow what coordinated actions they plan for the immediate future. IMF has been tracking global developments and has come up with sharp downward revisions of world trade and output growth in light of the latest geopolitical and economic developments (Table 1). 2022 is closing with much lower world output growth of 3.2% compared to 6% in 2021. Trade growth appears more depressed at 4.3% compared to 10% in 2021. What is worse, projections for 2023 remain gloomy with lower expected growth in trade and output. These projections augur ill for the Bangladesh economy, particularly its export prospects in the near term.

What is worse, projections for 2023 remain gloomy with lower expected growth in trade and output. These projections augur ill for the Bangladesh economy, particularly its export prospects in the near term.

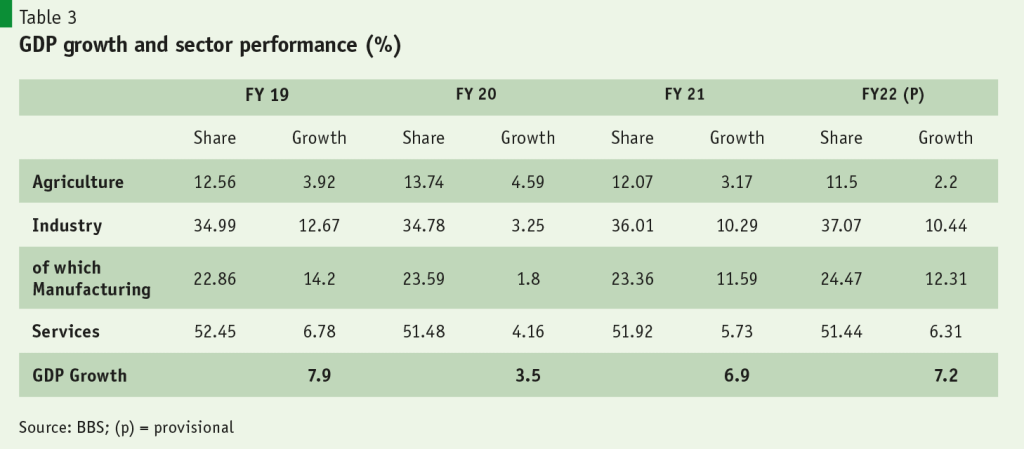

Given all the austerity measures coupled with unprecedented import restraint actions there is little doubt that industrial production (which contributes most to GDP growth) will be subdued. In the backdrop of a slowing global economy, our key development partners have made muted growth projections for the Bangladesh economy for the next year (Table 2) ranging from 6% by the World Bank and 6.8% by ADB, in contrast to BBS estimate of 7.5%, which is the figure coming out of the FY2023 Budget statement and is likely to be revised downward in light of the adverse trends in trade and domestic economic activity in the first half of FY2023. It would be realistic to expect a downward revision of BBS growth estimates for FY2023 to marginally below 7%.

Following resumption of post-Covid economic activity, industrial production has been strongly driven by robust export performance in FY2022. Despite the slowdown in the global economy the RMG sector, in particular, is expected to remain buoyant on the back of redirected orders from China over the near to medium-term as most Procurement Officers in EU and US have cited Bangladesh as the No.1 sourcing country over the next 5-10 years upon the decoupling trends in Sino-US trade. The export-oriented manufacturing in Bangladesh now dominates the manufacturing sector with 55% share.

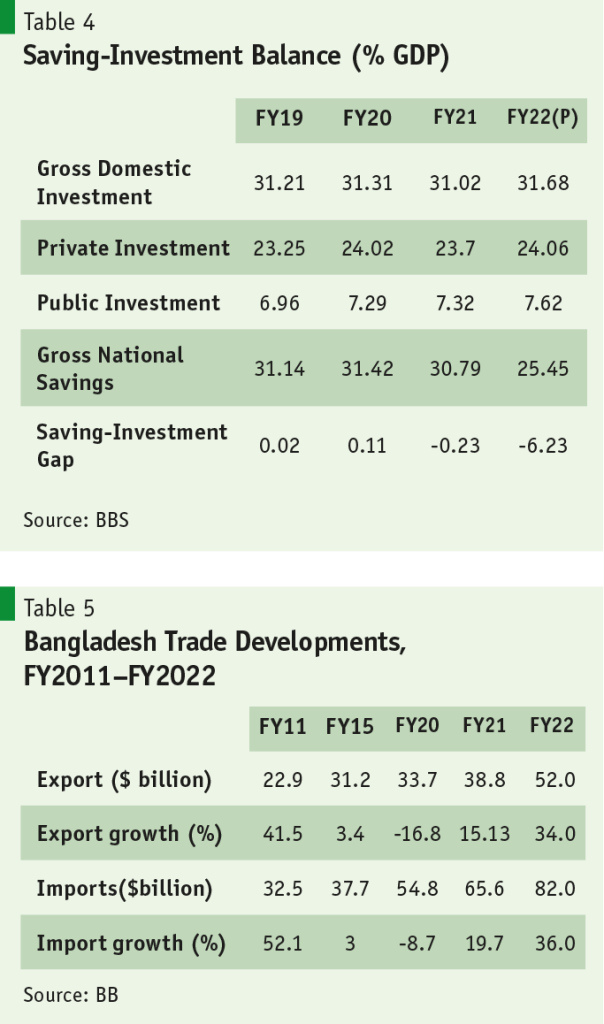

A quick review of the economy’s savings-investment balance is worthwhile. The economy’s growth is still driven by investment rather than consumption. Relying on past data the economy’s capital-output ratio (which defines investment requirement for output growth) works out to 4.5 so that to achieve targeted growth rates of 7-8%, the economy needs investment-GDP ratio of 31.5% or more. As data in Table 3 reveals, the economy finally achieved that requirement. However, the share of private investment, which remained sluggish until FY2021 showed some improvement in FY2022 while public investment continued to grow robustly.

Another notable feature of the savings-investment balance is the difference, called the savings-investment gap. For only a few years do we find the gap to be negative, implying an excess of investment over gross national savings (includes remittances) – what should be the case for a developing economy requiring massive investment in infrastructure. The fact that we find an excess of savings over investment for too many years gives an indication of under-investment of available savings. This is also reflected in the balance of payments data, where a current account surplus is recorded for 13 of the 21 years since FY2000. Indeed, the economy has lot of space for boosting investment with domestic and/or external resources.

Balance of Payments deteriorates under external shock

The robust trade outlook late in 2021 soon gave way to major disruption following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war in February 2022 and its aftermath. Of the several disruptive events that rocked the global economy, the following are notable as far as their impact on Bangladesh economy is concerned: 1) post-Covid supply chain disruptions were aggravated; 2) food and fuel prices rose sharply; 3) this was transmitted into broader commodity prices leading to global inflation; 4) US dollar appreciated by roughly 20%; and 5) China pursued lockdowns due to zero-Covid policy. Combined, these had damaging impacts on Bangladesh trade and balance of payments.

Despite building strong foundations for macroeconomic stability over a period of 25 years, cracks appeared in the system entirely due to external developments on which Bangladesh had no control. FY2022 was turning out to be a good year for the economy of Bangladesh. Until the end of December 2021, exports were surging at a record clip of 35%, but imports were surging as well, at a rate of 50%. FY2022 ended in June (Table 4, Chart 1&2)) with exports up 34% and imports at 35% (declining from the 50% clip due to high import prices and tightening of import and foreign exchange utilisation procedures in the closing months).

Our import bill typically is higher than export receipts by some USD 10-20 billion because import requirements rise with a fast-growing economy resulting in trade deficits which also tend to rise with growth. PRI research on import categories show that in the past decade, consumer goods make up only 18% of all imports, the rest (82%) is comprised of basic raw materials, intermediate and capital goods, all headed for the productive sectors of the economy, particularly industry.

It is notable that Bangladesh is primarily an exporter of manufacturing goods (95% of exports) which require imported inputs, unlike primary exports (like jute, cotton, oil) which are extracted from the soil. Consequently, a surge in exports automatically results in a surge in imports. There is no episode of an export surge that is not accompanied by an import surge. The label of an ‘import dependent’ economy should not be taken to describe a hapless situation because industrialization begets import reliance. But there is nothing bad about that. China, which is known as an export powerhouse and is the largest exporter in the world (exports of over USD 3 trillion) is also the second largest importer of the world (over USD 2 trillion).

Such export-import linked surges also lead to a spike in the trade deficit which need to be financed. Thankfully, Bangladesh has a ready source of import financing besides exports – export of factor services, namely, remittance from migrant workers. Rising remittances covered much of the trade deficit for most years since 2001, leaving modest surpluses in our current account, except in the past five years which experienced modest but sustained current account deficits (CAD). That is why the spike of 36% in imports which jumped to a whopping USD 82 billion led to a spike in the CAD (Chart 4 &5) causing huge pressure on the BOP and the exchange rate.

The challenge for any economy lies in its capacity to service its current account deficit through capital and financial inflows. Bangladesh has maintained a sustainable external balance for the past 25 years by maintaining moderate CADs at around 1% of GDP, with occasionally brief jump for one year or so (e.g. FY2012), well below the 3% threshold that is often considered as the red line for CADs (Chart 6). Indeed, since 2001 there were more years when CAD was positive than negative. Only in the past five years, CAD has been moderately negative around 1% of GDP.

There is also a concomitant relationship between the CAD and savings-investment balance. A positive CAD is usually the product of positive savings-investment balance, implying that the country – if it is a developing economy – is probably under-investing. It should not be a surprise to find a rapidly growing economy like Bangladesh running CADs and negative savings-investment balance at the same time. This is the picture that we see in the past 5-10 years when massive infrastructure projects have been commissioned and implementation is on-going. This investment drive could partially explain running persistent CADs in recent years.

For the first time, Bangladesh’s CAD shot up to 4% of GDP in FY2022, thanks to the import surge that was not matched by export surge plus remittance inflows. This is untenable. Cross-country and historical evidence reveals that persistent CADs of 3% or higher for three years or more invariably leads to financial crises and eventual downturn for the economy. So, Bangladesh Bank (BB) was right in moving swiftly to stem the tide of imports by invoking two measures: 1) imposing administrative curbs on imports (e.g. clamping down on opening LCs of unproductive imports); and 2) substantial depreciation of the exchange rate which resulted in a steep rise in import prices. However, we believe the additional measure of introducing multiple exchange rates was unorthodox, should be deemed temporary and abandoned sooner rather than later.

Gross FE reserves on the radar

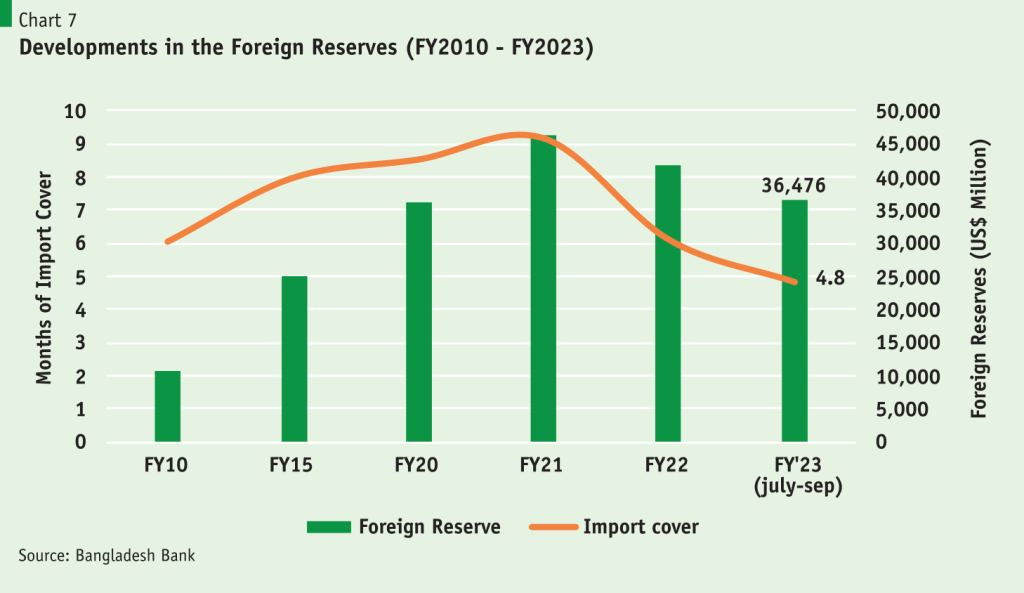

Ever since the external shock reached our shores, Bangladesh’s official reserves of FE, called gross foreign exchange reserves, has been on the radar not only of the media but also of IMF, the multilateral institution that monitors FE adequacy across nations. Bangladesh’s FE reserves reached its peak of USD 46.3 billion at the close of FY2021 with a coverage of almost 8 months of projected imports (Chart 7). That comfortable situation evaporated with the onset of external pressures shortly after February 2022, on two counts: 1) import surge; and 2) abortive attempt of BB to shore up the exchange rate by reportedly shedding some 10 billion out of official reserves until it became untenable.

IMF has raised some issues regarding the BB statement of FE reserves by bringing in the issue of net international reserves (NIR) — gross reserves minus short-term foreign currency drains — in determining adequacy. In this regard, the treatment of some USD 8 billion export development fund (EDF), a revolving fund that finances short-term import of inputs used in exports (mostly RMG), was disputed though not settled as potential short-term drain. Thus far, EDF stocks have held well thanks to the regular servicing of loans by exporters who treated this mostly as short-term trade credit. Current gross FE reserves (including EDF) of about USD 35.8 billion (end October) will cover about 5 months of projected imports which is reasonably adequate though addition of a few billion dollars would take FE reserves to a more comfortable zone. IMF commitment of USD 4.5 billion will do just that.

Exchange rate depreciates

Under these circumstances, it turned out that the efforts of Bangladesh Bank to maintain the BDT-USD exchange rate fixed at around BDT 86/USD by unloading foreign exchange in the market was no longer tenable. So, the exchange rate had to be floated resulting in a depreciation of about 20% reaching BDT 103/USD.

Source of the problem was import surge

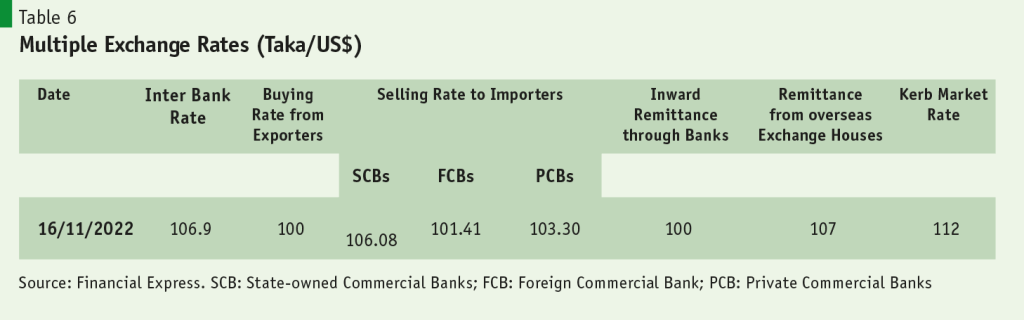

It was the import surge that created the exchange rate (ER) problem in the first place. The import surge was linked primarily to the export surge together with the global price spike in food and energy. The ER is simply the price of foreign exchange (e.g. USD). It is determined by the demand and supply of foreign exchange. The demand comes from imports of goods and services and the supply comes from exports of goods and services, in addition to official development assistance (ODA) received from multilateral and bilateral institutions (like WB, IMF), and inflows of FDI. The import surge, which was not matched by the sum of exports and remittance inflows, created an excess demand situation, putting pressure on the exchange rate to depreciate, i.e. BDT price of USD to rise. Though Bangladesh moved into the ‘floating’ exchange rate regime back in 2003, the actual practice was a ‘managed float’ – perhaps too much managed to make it look almost like a ‘fixed’ exchange rate system. For instance, the BDT/USD rate remained at BDT 85-86 for nearly three years until May 2022. After drawing down some USD 10 billion from FE reserves BB had to let the ER float. However, rather than settle at a uniform ER, a system of multiple rates was introduced – a rate for exporters, another for importers, and still another for remitters (Table 5).

The expectation is that this measure is temporary and will be dispensed with soon. For the longer term of course, it is important to recognise proper exchange rate management as a development strategy, as critical as the strategy of export led growth.

Trade economists are not great fans of such multiple ER systems. Few countries have actually resorted to multiple ER systems. Usually, in times of economic turmoil, it is a mechanism by which governments can quickly implement control over foreign currency transactions. Such a system can buy some extra time for the governments in their attempts to fix the underlying problem in their balance of payments. Bangladesh economy did face an external shock that gave BB some justification for resorting to this extreme measure; but suffice it to say that it is a highly complex and inefficient system for alleviating excess demand pressure on foreign reserves. Therefore, it should be transitional and short-lived, and disbanded sooner rather than later.

Of late, it is clear that remittance inflows through informal channels have been rising, as the data shows no sharp rise in monthly inflows through formal channels. With some 900,000 migrant workers having left for employment abroad by September 2022 (a record), mostly to the Gulf states, which are booming on the back of gas and oil price hikes, the decline of remittance inflows from about USD2 billion monthly (July-Aug) to USD1.6 billion in Sep-Oct, indicates flows through informal channels are on the rise. This has to be reversed. One quick way to do that is to equalize the formal remittance exchange rate with that on the kerb market. Simultaneously, the messy system of multiple exchange rates needs to be phased out by bringing on a ‘unified and flexible exchange rate regime’.

To restore balance in the BOP, and bring current account deficits to sustainable levels like before, the road is pretty straightforward: imports will have to be restrained for a brief period while exports and remittances (plus ODA and FDI) generate an adequate flow of foreign exchange to keep official reserves accumulating rather than depleting. That will require a return to orthodox exchange rate policy, that is, moving as quickly as possible to a unified and flexible (or floating) exchange rate system for all international transactions. The move towards a unified and flexible exchange rate need not be instantaneous, but can be done with incremental adjustment until such time as the external sector balance is restored. As the Chinese saying goes, if you don’t know how deep the river is ‘you should cross the river by feeling the stones’.

Make no mistake, restraining imports in an export-led economy will have its own setbacks, as Bangladesh imports are overwhelmingly (some 80%) destined for the productive sectors of the economy. So, the policy brakes on imports need to be as short-lived as possible leaving market forces to get back in charge. While exchange rate depreciation is dampening the demand for imports, on the one hand, it has added fuel to the fire of hike in import prices, on the other. So, managing domestic inflation and managing exchange rate stability has become a dual-edged sword that honestly is not so easy to manage in these challenging times.

Make no mistake, restraining imports in an export-led economy will have its own setbacks, as Bangladesh imports are overwhelmingly (some 80%) destined for the productive sectors of the economy.

Our external balances and the exchange rate in particular will have to be on the policy radar for some time to come as we grapple with the possibility of adverse external forces reaching our shores with the fury of a ‘perfect storm’, as the former US Treasury Secretary, Larry Summers, would like to describe it. Our hope is that calm minds prevail in managing the exchange rate such that the external sector is handled with the deftness it deserves in order to help resume the path of sustainable growth in imports, exports, remittances, and consequently, ensuring stability in the balance of payments. These external sector indicators are conjointly the most critical drivers of our macroeconomic stability and prosperity.

Imported inflation shock and unorthodox remedy

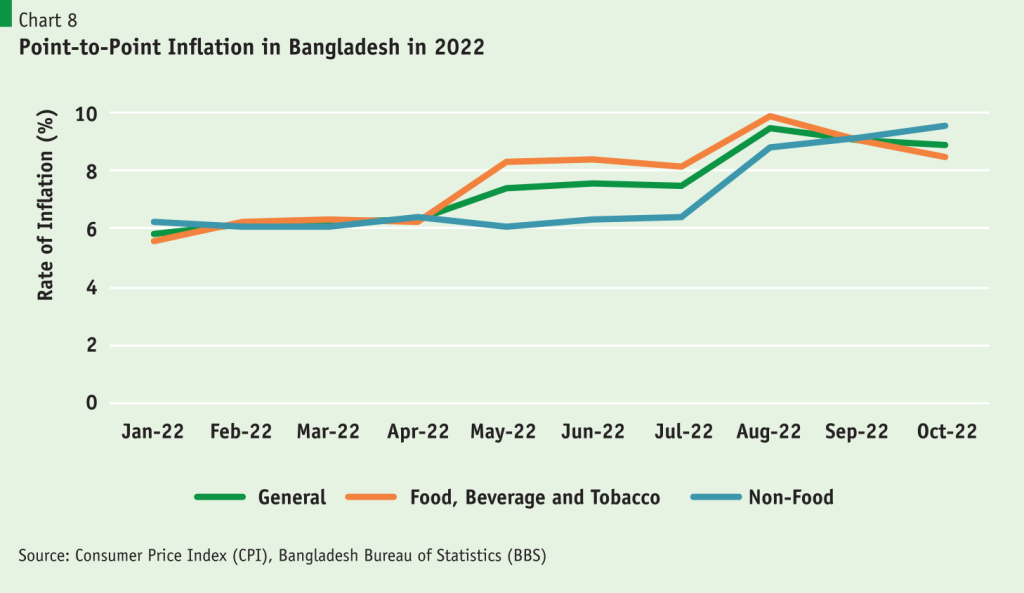

Unlike inflation in some Latin American countries inflation in Bangladesh is known to be moderate and stable. Inflation averaged 5.6% during the period of the 6th and 7th Five Year Plans (FY2011-2020). That situation has changed dramatically over the past few months. Official statistics indicate point-to-point inflation at 8.9% in October 2022, though, 12-month moving average CPI index is about 7% (Chart 8). That is the highest in a decade or more. The poor are hurting most. Fixed income earners are finding it difficult to make ends meet. Something needs to be done.

But this inflation is different. The spike in domestic price level is not the result of a crop failure in our agriculture or disruption in industrial production. It was external events that caused it. It can be euphemistically described as ‘imported inflation’ because its roots are to be found in recent external developments: post-Covid supply chain disruption, Russia-Ukraine war, hike in food and energy prices and, eventually, global inflation.

Practically all products that Bangladesh imports have seen a rise in prices, though international energy prices have recently abated somewhat. Food prices still remain at record levels thanks to the continuation of the Russia-Ukraine war that has impeded grain shipments from Europe’s grain basket – Ukraine. Consequently, our economy has experienced a rise in the prices of traded goods as well as non-traded goods (services, transportation and the like). Clearly, this inflation is import-induced.

In the past fiscal year, we have seen an import surge of 35% which was associated with an export surge of 34%. The import surge resulted in merchandise imports of USD 82 billion in FY2022 against total imports of USD 60 billion in the previous year. The rise in imports was partly due to rise in global prices of imported goods but largely due to the import-export linkage that occurs when an economy primarily exports manufactured goods. The rise in imports was not matched by the inflow of foreign exchange from exports and remittances resulting in a record current account deficit of USD 18.7 billion or 4% of GDP. This put pressure on the BDT-USD exchange rate which could not be held at the old rate of BDT 86/USD even after disgorging some USD 10 billion from the official foreign exchange reserves of Bangladesh Bank.

Quite appropriately, BB had to let the exchange rate float resulting in a depreciation of over 20% in a matter of weeks. Coincidentally, this matches the appreciation of the US dollar by some 20% over the past year. Note that most if not all of Bangladesh’s international payments involving trade in goods and services have to be made in US dollar – the currency that is the means of payment for over 75% of all international trade and capital transactions. If the Taka did not depreciate, the exchange rate would have been over-valued by 20% for just the reason of dollar appreciation.

So domestic prices of imports have risen on two counts: one, global inflation that saw the rise of food and energy prices with spillover effects on all other traded and non-traded goods and services; two, the exchange rate depreciation raised the landed price of imports by the extent of the depreciation. Contiguously, as domestic price of imports rose, so did the price of import substitute products produced domestically. All this translates into a rise in the domestic price level – inflation. Bear in mind that 80% of our imports comprise raw materials, intermediate inputs, and capital goods, all of which are destined for the productive sectors of the economy. This contributes to what is called a ‘cost-push’ inflation that was transmitted from across the border – a supply shock inflation indeed.

In the circumstances, I will argue that this inflation might not be tamed by the standard demand-side management that we see in most developed economies today. Those economies were engaged in monetary easing for almost 12 years since the outbreak of the global financial crisis (GFC). This was at a time when inflation was running at below 2 percentage points and interest rates were even lower. They have now reverted to a course of monetary tightening (restraining credit demand) to deflate the rise in prices on account of the post-Covid supply chain disruption and the Russia-Ukraine war. Interest rates have risen in order to tame inflation by restraining demand.

That is unlikely to work in the Bangladesh scenario. Quashing inflation has to start at the border. One phenomenon already mentioned is the 20%+ exchange rate depreciation that was implemented within a matter of a few weeks. Quite apart from the transmission of price effect to the domestic market there are three simultaneous impacts of note. First, a 20% depreciation of the Taka-US dollar is the equivalent of a 20% spike in tariffs across-the-board. This comes from the fact that assessable value (on which import taxes are assessed by customs) of all imports are up by 20%. So, any ad valorem tariff now goes up 20%. Simply put, a 10% tariff on imports worth USD 100 at BDT 85/USD would have been BDT 8500. A 20% depreciation (BDT 102/USD) now makes the USD 100 imports equivalent to USD 10,200 on which a 10% tariff yields revenue of BDT 1020, i.e. 20% higher revenue than what would have been generated by the old exchange rate. Thus, the exchange rate depreciation of 20% is the equivalent of a 20% hike in tariffs (10% tariff becomes a 12% tariff rate). This is a windfall tariff hike for NBR, without the need for any legislation!

Second, applying the principle of uniform tariff protection, a 20% exchange rate depreciation has the effect of raising effective rate of protection by an equal 20%, as it raises the tariff-induced price of output and inputs by the same percentage point. That means import substitute industries get a boost from the exchange rate depreciation as well. Caveat: since domestic import substitutes are imperfect substitutes of imported products output prices may not rise as much as the tariff spike. So, a rise in effective protection may not exactly match the rate of depreciation but there will be a rise nevertheless.

Third, exporters get an extra 20% from every dollar of exports – we may call it a subsidy that is different from the cash subsidy they receive which comes out of the government budget.

Quite apart from the fact that consumer goods prices have risen, since 80% of imports are destined for the productive sector, costs of production in the industrial, agricultural, and services sector have increased to push up output prices as well resulting in a point-to-point general inflation rate of 8.9% in October 2022. In large part this uptick in inflation is import-induced. One effective instrument to quash this import-induced cost-push inflation is to use the tariff handle. Since NBR finds itself benefiting from an unanticipated 20% spike in tariffs it is well placed to make some downward adjustment in tariffs that could help quell domestic inflation without any loss of revenues. Even a modest reduction in tariffs will have noticeable impact on reducing inflation.

There is no issue of revenue loss to NBR because it comes out of the windfall. Domestic lobbies favoring import substituting protection have no reason to complain as the tariff reduction comes out of the 20% extra protection from exchange depreciation. The fact is larger the neutralization of the price effect of exchange rate depreciation greater will be the downward impact on the current import-induced inflation.

At a time when the interest rate handle has been effectively frozen so credit restraint (i.e. demand restraint) is no longer possible through raising interest rates, the tariff handle remains as a potentially lethal instrument to stifle imported inflation. The sharp depreciation of the Taka-dollar exchange rate was an essential requirement to combat the challenging impacts on our balance of payments emanating from external developments. Nevertheless, it presents an unorthodox scenario for neutralizing an import shock induced inflation given Bangladesh’s current tariff structure. PRI research finds definitive scope for using the tariff handle to remedy the bug of imported inflation.

Food prices up but Bangladesh stocks adequate

The Russia-Ukraine war has disrupted food production and impeded global supplies from a region that exports a third (36%) of the world’s wheat. Ukraine was known as the ‘bread basket’ of Europe for its massive production of surplus wheat, maize and other agricultural products. The war has impeded Ukraine’s export capacity from sea lane blockages and labor shortages due to conscription and population displacement. Access to vital agricultural inputs such as fertilizers is also constrained. The conflict has added to food supply chain pressures by pushing up costs of fertilizers, animal feed and energy. This has led to a rise in food prices globally, as well as in Bangladesh.

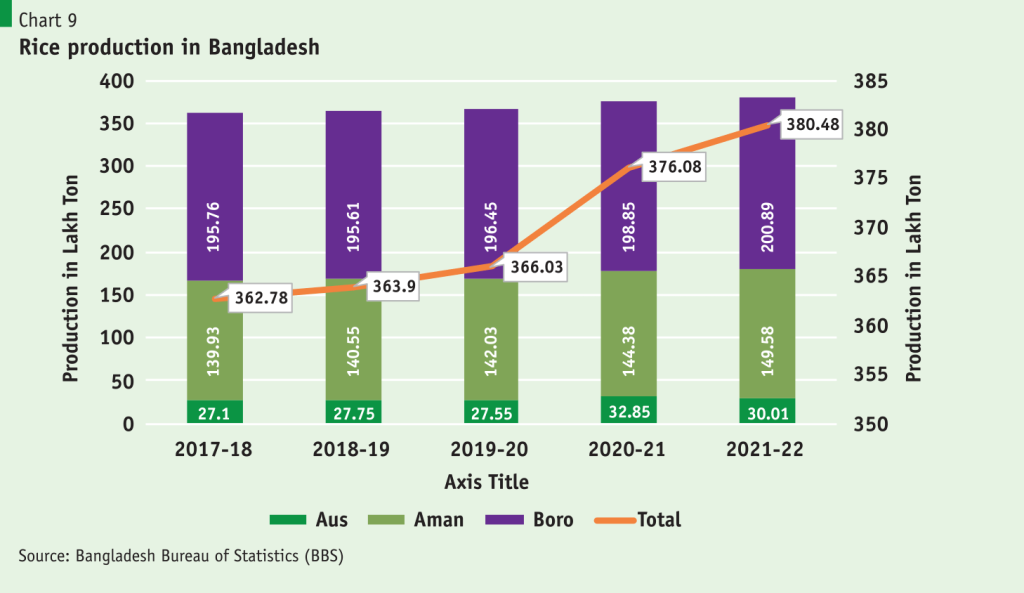

Though population of Bangladesh has more than doubled since independence production of food grains quadrupled over the past fifty years making the country approach food self-sufficiency. In recent times, food grains production (particularly rice) has been rising modestly (Chart 9), enough to keep any food security concerns at bay. In the past year, domestic rice production at 39 million metric tons (MMT) appears adequate according to estimates of food supply and net food grain requirement by Food Planning and Monitoring Unit (FPMU, Nov 2022). FPMU informs that public stocks at 1.62 MMT is also satisfactory, while agricultural experts project that private stocks are likely to be higher than before as they tend to consolidate stocks in times of uncertainty.

All in all, this state of play in the food grains sector should allay any food security concerns for the time except to make sure that the targeted import of 4 MMT of rice and wheat in FY2023 is not impeded by any dearth of foreign exchange (unlikely). For the longer-term interest of maintaining food security, agricultural experts (e.g. Dr. Sattar Mandal) recommend: 1) keeping up the momentum of rice production by harnessing modern techniques; 2) pursuing a combined policy of cost support to fertilizer, diesel, and other inputs to protect farmer’s incentives; 3) diversifying the food bundle by substituting rice-based foods for wheat; and 4) involving private sector food industries in a major way.

Deficits, debt and the external shock

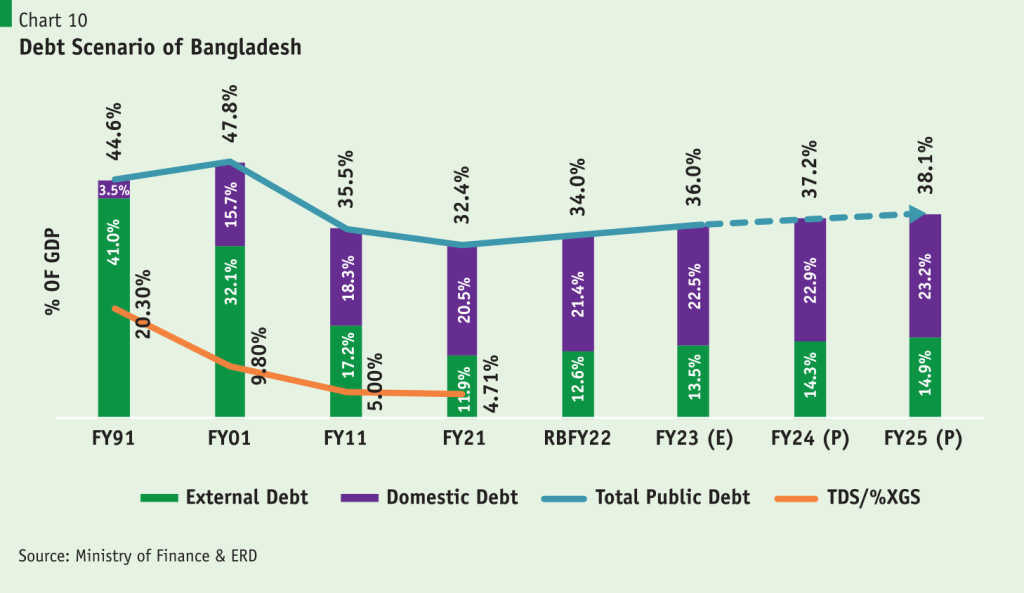

For almost 30 years, Bangladesh’s prudent macroeconomic management has earned appreciation. The budget deficit is manageable, an indicator of the policy’s effectiveness, and the economy as a whole is stable (sustainable current account balance for most years). Since the economy entered the 21st century, a stable and manageable budget deficit has been underpinned and limited to 5% or less of GDP. In an effort to help the economy recover from the effects of Covid-19, the government declared a large expenditure budget for FY2022. This increased the fiscal deficit (6.2%); however, it has now been revised down to below 5.5%. Actually, until 2015, the fiscal deficit averaged under 4% of GDP for 25 years.

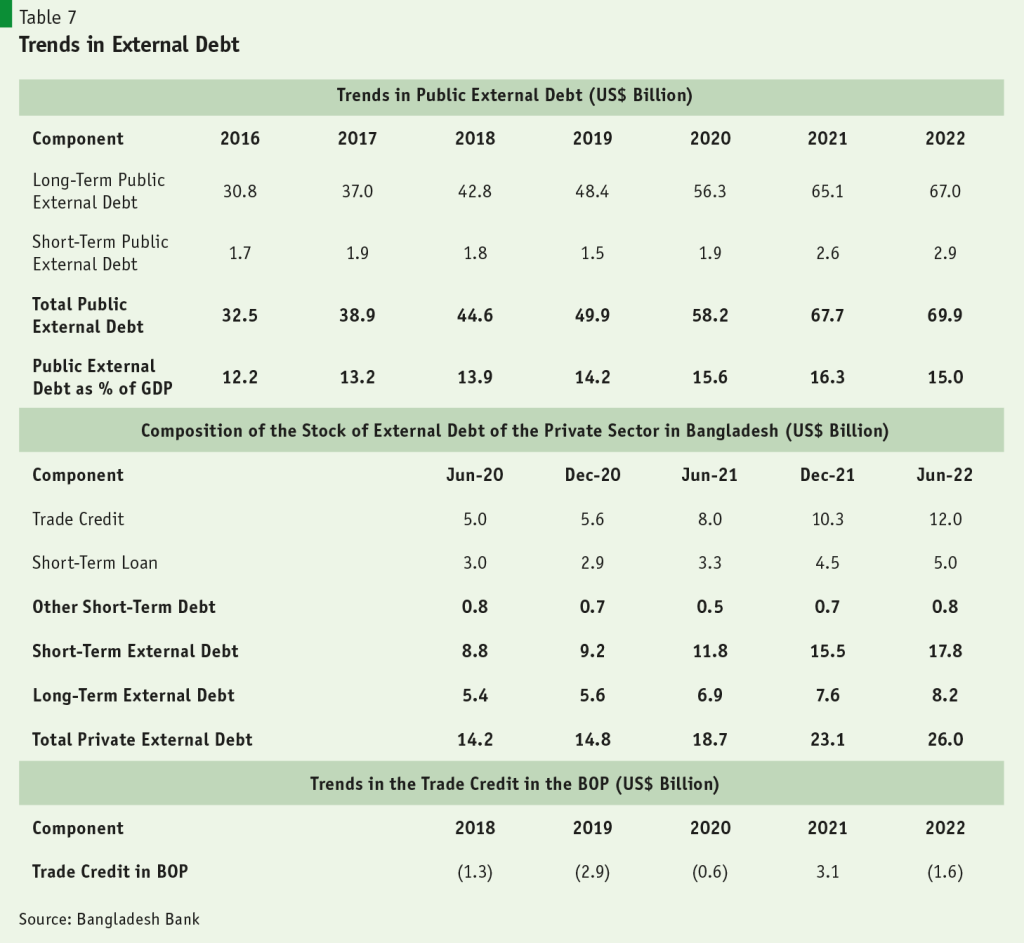

Fiscal deficits result in national debt. To meet the deficit every year, the government borrows from both domestic and external sources. The country’s public debt-to-GDP has dwindled over time, reaching 34% in FY2022, from 44.6% in FY1991 (Chart 10). In FY2022, the share of external debt stock is estimated at 16% of GDP; compared to 41% in FY1991. However, external debt servicing has multiplied in terms of local currency as a result of the recent exchange rate depreciation, and the dollar crisis may put the government under strain in the upcoming days. For instance, considering a 20% appreciation of the dollar into account would result in USD 60 billion more being spent in local currency on servicing the public sector’s debt (which was 33 billion in FY2021).

However, external debt servicing has multiplied in terms of local currency as a result of the recent exchange rate depreciation, and the dollar crisis may put the government under strain in the upcoming days.

In terms of long-term external debt (as of June FY2022), the stock has risen to USD 67 billion (95.8% of total stock) from USD 30.8 billion in FY2016, while short-term debt increased from USD 1.1 billion to USD 2.9 billion for the same period (Table 6). Moreover, the private sector-led external debt crossed USD 25 billion for the first time in FY2022, where most of it was borrowed in short-term. Since 2018 and onwards, short-term debt has been experiencing a double-digit figure and rising over time.

However, the idea of adding public and private external debt would be like adding apples and oranges. Trade credit is the largest component of ST Private external debt. It is usually an advance over export orders to be settled with export proceeds. It does not have a significant impact on the BOP. No textbook rule says what the level of external debt should be and what should be the ideal rate of growth annually. IMF/WB, which monitors external debt across economies, usually sets some guidelines, but there is nothing sacrosanct about them. Each country will have to set its own guidelines, using IMF/WB guidelines as reference. One strategy would be to limit the annual growth rate of external debt below the growth rate of GDP. Higher GDP growth could allow a higher intake of external debt.

Epilogue……and the way forward

Calendar year 2022 is closing after posing many policy challenges for the economy. Export proceeds and remittance receipts have not kept up the buoyancy experienced until September this year. Bangladesh Bank had to put the brakes on the massive import surge of last year, which brought on the BOP crunch in the first place. The approach taken was that the substantial exchange rate depreciation was not enough to stem the import tide, so administrative curbs (e.g. curbs on LC opening) had to be put in place. That has started working as of November and the expectation is that by January-February 2023, the current account deficit will have narrowed to reasonable levels provided the flow of exports and remittances continues to tick. In this backdrop, 2023 looks to be a year of uncertain prospects for the economy, until some positive trends emerge early in 2023. In this backdrop, the IMF commitment of USD 4.5 billion could be a game changer in restoring confidence in the strength of the economy to pursue its medium-term goals of preparing for the impending graduation out of LDC status and moving up to the Upper-Middle Income Country (UMIC) category by 2031.

Globally, gloom and doom about prospects of output and trade growth are widespread across developed economies and IMF projections provide no sign of light in the near-term outlook. This comes at a time when analysts reckon that globalization is in retreat. Globalization was the one positive force driving global prosperity for several decades in the past. After decades of fostering trade openness, the new approach seems to be to treat trade as a zero-sum phenomenon. A combination of ideas like ‘re-shoring’, ‘friend-shoring’, and ‘strategic autonomy’ are on the march, all sounding like a return of protectionism.

The emerging geopolitical trend is the Sino-American decoupling which threatens to leave the global economy, supply chains and markets more balkanized and fragmented. Though President Biden promised no prospect of a return to ‘Cold War’, their economic and trade relationship seems to be turning colder by the day leading to something of a Thucydides Trade Trap in the world economy. Chinese exports were a major factor in keeping inflation low in developed country markets. In the absence of a China factor in international trade world markets are likely to sustain a period of higher prices — a stagflationary prospect in a slowing global economy.

The silver lining for Bangladesh in this backdrop comes from what the chief procurement officers (CPO) of leading retail companies in Europe and USA say about which country will be their top sourcing nation in the next five to ten years. Bangladesh was mentioned as the No.1 sourcing country by 90% of the CPOs, not Vietnam or India, or any other, according to a survey by McKinsey. Capacity and pricing criteria played the predominant role to seal this position for Bangladesh. Redirection of apparel orders away from China in substantial volumes is expected over the medium-term. A strong pick up in export orders in the coming months is being reported by BGMEA. If the latest BGMEA Apparel Expo-2022, which was attended by numerous international companies is any guide, the future of our RMG industry looks brighter than its past.

In concluding, I leave with the message that stabilizing the macroeconomy must be the uppermost policy priority. But it must be done appropriately. The first item on the agenda should be to move out of the multiple exchange rate system as soon as possible, unifying the exchange rate and making it flexible and market-determined. A build-up of reserves should be next on the agenda. With imports restrained, a pickup of exports and remittances is absolutely essential for that to happen. Come February, as IMF releases its first tranche and World Bank and others chip in, that should further stabilize the balance of payments. The inflation bug would then have to be quashed with tightening of fiscal and monetary policies.

Addressing macroeconomic challenges to restore internal and external stability will remain the policy priority in 2023 in order to put Bangladesh economy back on its higher growth trajectory. Beating heavy odds has been an integral part of Bangladesh’s journey of economic progress, often referred to as ‘Bangladesh surprise’. Next year should be no different.

Research support to the SOE report was provided by PRI Senior Research Associates Promito Musharraf Bhuiyan, Sumaiya Fatima Farah, Karisa Musrat, Md. Masudul Haque Prodhan, Tanzila Sultana and Research Associate Md. Salay Mostofa.