Tackling the External Deficit – The Interest Rate Imperative

By

Arecent Bangladesh Bank Policy Note provided a timely alert on the current macroeconomic situation. Titled the “Impact of Exchange rate and Global Commodity Price inflation on private sector credit,” it was written by the Chief Economist, Dr Habibur Rahman, and his two colleagues, Dr Md. Salim Al Mamun and Ms. Nasrin Akter Lubna and acknowledged the “instruction, guidance and valuable suggestions” from the Governor, Dr Abdur Rouf Talukdar. Although the note stated that it only expressed the authors’ views and not the Bank’s official stance, it is fair to assume it expresses the Bank leadership’s evolving thinking.

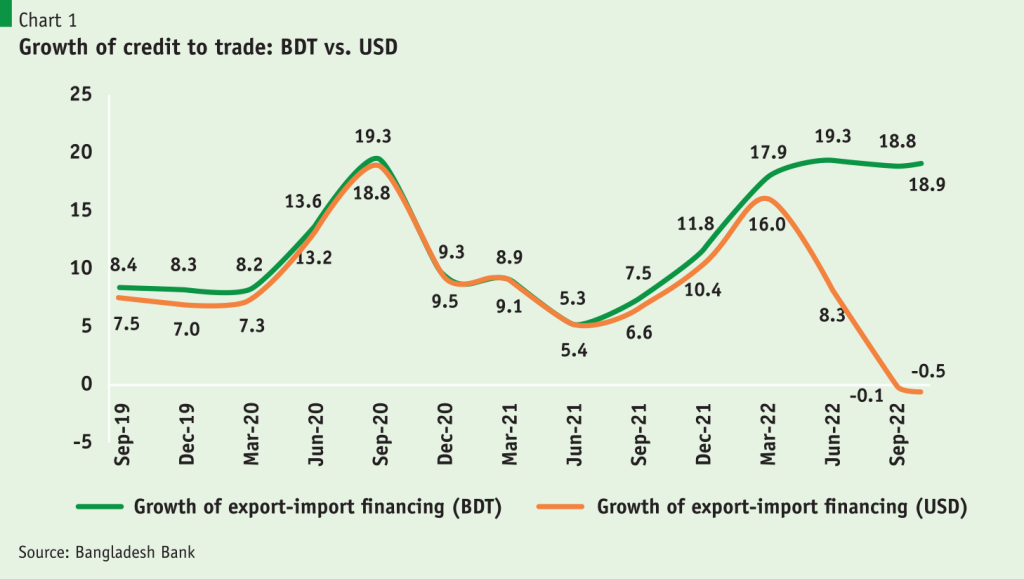

Ostensibly, the main point is that the marked uptick in credit growth to the private sector should not be seen as excessive or inflationary. Rather, after adjusting for the high commodity inflation and exchange rate depreciation, real private sector credit growth is much less. The export-import credit growth turned negative in dollar terms last September and October (See Chart 3 from Policy Note). The note also suggests that the combination of global commodity price inflation and exchange rate depreciation has mainly been driving private credit growth.

So far, so good. The main point is factually correct, and the last point is reasonable even if not conclusively made. But if all this seems a bit academic, that is not the case.

The concluding section of the note has quite dramatic policy relevance. Three significant macroeconomic management challenges for Bangladesh are discussed there. One, the combination of global commodity inflation and exchange rate depreciation creates an asymmetrical impact on trade finance surges import payments relative to export receipts. That creates a “liquidity mismatch” for banks: advances are growing faster than deposits.

…the combination of global commodity inflation and exchange rate depreciation creates an asymmetrical impact on trade finance surges import payments relative to export receipts. That creates a “liquidity mismatch” for banks: advances are growing faster than deposits.

Second, ongoing exchange rate depreciation adversely affect private firms’ and governments’ ability to make debt payments as they become larger in Taka terms. These pending debt payments and international commodity import prices – payable in dollars – also lead to a currency mismatch and put pressure on foreign exchange reserves. Third, it notes, quite rightly, the continued risks of global commodity price increases and imported inflation will affect the budgets of firms and the Government, requiring belt-tightening.

So, what is to be done? The note concludes, with some former U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan-style ambiguity, that “there are not many policy options available other than making appropriate supply side interventions while managing the exchange rate adversities requires market-oriented flexibility”.

Responses to the note

I have two responses to this note. First, I welcome the seriousness with which the current situation is addressed. It is a departure from the “don’t worry, be happy” style of wishful thinking that we sometimes see: the problem is being solved, and good days are coming.

That is likely not the case, and the Policy Note has done a service by alerting us to this. Consider that in the first four months of the current fiscal year, we have imported over USD 27 billion of goods and run a trade deficit of USD 10.7 billion. While our exports crossed USD 5 billion in November, the Bangladesh Bank website has not provided import figures. On the overall current account side, our deficit is USD 3.7 billion over the same period. Annualized, the current account deficit stands at about 4% of GDP. Beyond financing these deficits, we have also had to make debt payments to the Asian Clearing Union recently. Altogether, our foreign exchange reserves have declined by another USD 8 billion in the first five months of this fiscal year. That places our reserve import cover at less than four months if we use the IMF’s definition or five months if we use the Government’s definition.

Altogether, our foreign exchange reserves have declined by another USD 8 billion in the first five months of this fiscal year. That places our reserve import cover at less than four months if we use the IMF’s definition or five months if we use the Government’s definition.

Clearly, the situation is fraught, and the Bangladesh Bank policy note dutifully points out that we are vulnerable to shocks. It rightly calls for action to reduce demand for imports and asks for using flexible market instruments. That is, it seems to imply, quite wisely, using administrative methods and higher tariffs to reduce import demand is not adequate to reduce import demand.

That leads me to my second point. The note is not explicit enough regarding instruments. It indeed refers to the need for exchange rate flexibility, which is already partially in place, and the Bank has just depreciated its exchange rate by one more notch. But beyond exchange rate flexibility, the Policy Note may also be asking for interest rate flexibility. If correct, one wishes it was more explicit. Making interest rates flexible and increasing them have become an urgent necessity.

Suppressed interest rates are harming the economy

The reality is that using only exchange rate movements without interest rate action and flexibility will deepen the crisis. Bangladesh Bank has increased its overnight lending (repo) rate a few times to 5.75%. But oblivious to exchange rate pressure and liquidity demands, it has held fast its main policy rate of lending to Banks at 4% throughout this crisis, and commercial Bank lending rates have also been stuck at just over 7%. We know these long unchanged rates are below market rates because the market-based call short-term money interest rates have doubled since last December.

Further, Banks’ saving and lending interest rates are currently lower than inflation rates or negative in real terms. If this continues, it will benefit both consumers and firms to borrow money and spend now, especially on imports, and repay later – or not- if they are well connected.

There are five ways these negative real interest rates are hurting the economy. First, as just noted, there is no reason for either consumers or firms to reduce demand for credit and spending at these rates. The fundamental reason for having a current account deficit is because we spend more than what we earn. Not adjusting interest rates is, thus, an assured way to deepen our reserves problem.

The fundamental reason for having a current account deficit is because we spend more than what we earn. Not adjusting interest rates is, thus, an assured way to deepen our reserves problem.

Second, suppressing interest rates means a wealth transfer from the primarily middle-class savers and pensioners, whose savings are taxed, to the mostly wealthy borrowers, who get subsidized credit. Further, credit will have to be rationed at below-market rates because there will be excess demand. Likely, favoured borrowers, many of whom have already caused the economy a lot of pain, will gain again.

Third, given the insider-lending biased governing structures of Bank Boards such rationing of capital will probably lead to capital flows to favoured borrowers. That will mean a misallocation and lower productivity of capital and investment. These will have long-term consequences of lowering growth.

Fourth, depending only on the exchange rates to adjust can create an exchange rate depreciation-inflation spiral: depreciation will increase inflation, leading to further depreciation. Such a spiral will hurt most of all wage-earning workers and the middle class, but will also adversely affect producers by creating uncertainty. The deeper danger is that persisting with fixed interest rates could make the depreciation-inflation spiral part of expectations, self-fulfilling, and runaway. If that happens, the Government will lose credibility and our problem will become vastly deeper.

Fifth, it hardly needs to be stressed that introducing such volatility in a banking system burdened by high levels of nonperforming assets brings a significant risk of causing a systemic crisis in the economy. The Banking system has already been weakened by misgovernance, misallocation, bad loans and interest rate suppression. As a result, the returns on equity of Banks have decreased precipitously from 26% to 5% or less in recent years. Currently, non-performing loans are anywhere from BDT 1300 billion, per Government estimates, to about BDT 3000 billion per IMF estimates (Ahsan Mansur, Daily Star, 29 November, 2022) – i.e. from 3 to 7% of GDP. In effect, the Bangladesh Banking system that is already very shallow with less than 48% of private sector credit to GDP ratio is even shallower in practice as more than 10% of its assets are inert.

Arguments for suppressing interest rates to help industry are self-defeating

Three arguments are made to keep interest rates suppressed. One argument is suppressing interest rates will help out borrowers and the Government from facing higher interest payment charges. But in the face of large external deficits, the whole point is to make borrowers pay more interest and thereby restrain their demand, reduce our domestic absorption and the current account deficit. While raising interest rates to reduce demand may dampen, by design, short-term growth rates, it will help long-term growth by keeping the economy stable, lowering risks and maintaining investor confidence.

Without such action, the risk will be to destabilise the economy by sharply reducing reserves and risking runaway depreciation and inflation. Such destabilisation can create huge losses, some even terminal, to the balance sheets of Banks and the corporate firms that suppressed interest rates are trying to help. Thus, such interest rate inaction can become self-defeating.

That is the reason why, like most Central Banks around the world, the Reserve Bank of India – which is facing similar current account deficit pressures – has raised its main policy rate of lending to Commercial Banks to 6.5%. By not similarly adjusting interest rates, we are deepening the current account deficit and reserves problem and bringing hardship to workers and the middle class through inflation.

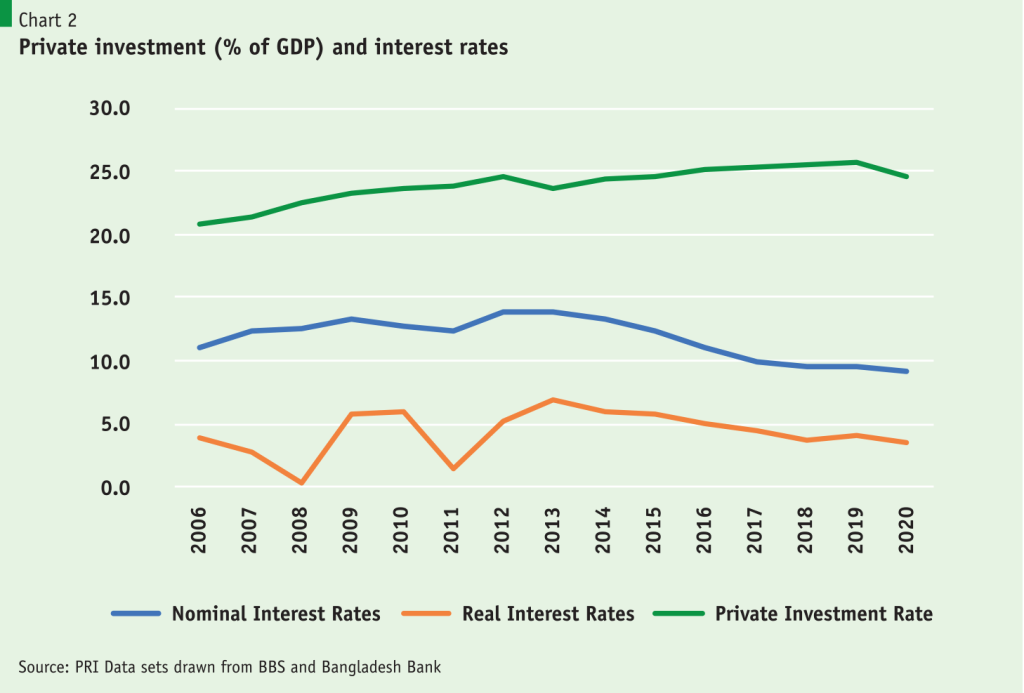

The second argument for keeping interest rates low is that suppressed interest rates will support higher investment and long-term growth. In practice, however, the relationship between interest rates and investment activity is complicated by several other factors. Thus, as shown in the diagram below, there is no statistically significant relationship between private investment rates and nominal or real interest rates in the case of Bangladesh for the past 15 years. When interest rates increased from 2006 to 2012, private investment rates also increased. On the other hand, when nominal interest rates and, to a lesser extent, real interest rates have declined from 2013 onwards, private investment rates have remained standstill.

Thus, because the interaction between interest rates and investment is complicated by other factors, under certain conditions not raising interest rates and increasing risks can lower investment rates. That may be happening in Bangladesh now. The conditions are which these can happen are discussed in the Annex.

A third argument for caution in using monetary policy and interest rate actions are that these can take time to have an impact because monetary transmission mechanisms are underdeveloped in lower-income economies. Thus, the impact of interest rates could come later when the crisis will have passed and then it will create more costs than benefits. As it happens the transmission speed of interest rates and monetary policy action is asymmetrical depending on the objective: their transmission and impact may indeed be slow when the objective is to stimulate demand during economic slumps through lower interest rates and pumping higher liquidity. The effect here is analogous to pushing on a rope – that may not work if the demand is weak, and the rope is slack.

However, interest rates and monetary policy should have a swifter impact when the aim is to reduce domestic absorption and aggregate demand by raising interest rates and the costs of funds when demand is high. Pulling at the rope that is already taut has more and faster impact. Bangladesh clearly is at this scenario when excess aggregate demand is creating high, unsustainable current account deficits. The rope is taut and needs to be pulled. And if transmission takes some time, the action needs to start earlier not later.

Annex: The Relationship between Interest Rates and Investment are Complicated by Other factors – How not increasing interest rates can lower Investment.

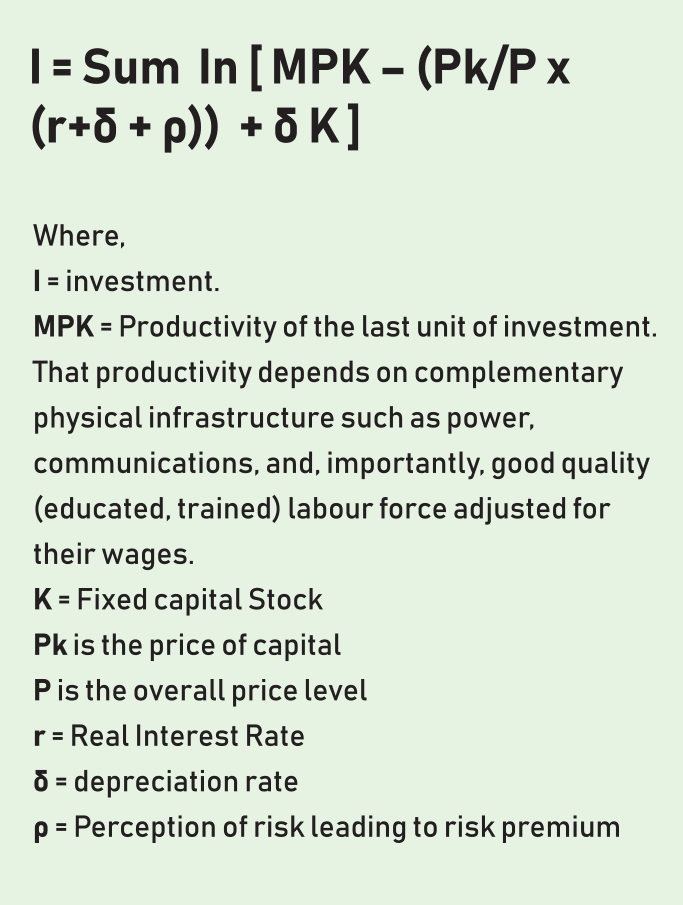

Sometimes in economics, complex matters are best explained with a little algebra. Thus, the reasons for the ambiguous effect of interest rates on investment are best brought most clearly by the standard investment equation such as below. Here the basic logic is investment – both new and incremental – depends on expected profits: revenues minus costs.

That is investment decision depends on the marginal productivity of adding one unit of capital K (i.e. MPK) less the costs of that unit of capital. The costs are the relative price of capital goods to the general price level, times the interest cost (r), the depreciation of existing capital stock ( δ ), and the last term δ, representing risks.

This simple equation gives a quite comprehensive picture of how investment decisions are made. But let us focus here on interest rates (r) and two other key variables that are relevant.

1. Other things unchanged if real interest rates went up, investment would fall.

But at present in Bangladesh, at least two other variables are at play.

2.Exchange rate is depreciating due to the current account deficit – i.e. excess demand for foreign exchange and excess supply of Takas, but they are depreciating even more because of the absence of interest rate increases. That is the earnings on Taka is lower than what it would be with higher interest rates. Then exchange rates will depreciate faster. Further, proportionately more capital goods than other goods are imported. Then under these two conditions, relative prices of capital goods, Pk/P, would increase faster because of the absence of interest rate increase. This would cause investment would fall.

3.Further, if due to the absence of interest rate increase, the perception of instability and risk in general, and expectations of exchange rate depreciation increased then the risk premium ( ρ ) would be higher and investment would also fall.

In the current situation of Bangladesh, it is straightforward to foresee scenarios when conditions (2) and (3) would dominate (1) and thus investment could fall in the absence of an adequate interest rate increase.