Avoiding the Middle-Income Country Trap Challenges and Opportunities for Bangladesh

By

A major challenge in development is that developing and emerging market economies fall into the Middle-Income Country Trap (MIT). That term refers to the empirical observation of the slowdown of productivity growth of middle-income countries when they approach higher income per capita levels. Consequently, relatively few higher middle-income countries have been able to cross over and become high-income economies. Hence, countries such as Argentina, Malaysia, Turkey, and others have been marking time for decades at the doorstep of higher-income economies without becoming one. Some even reverse, go backward, and become poorer.

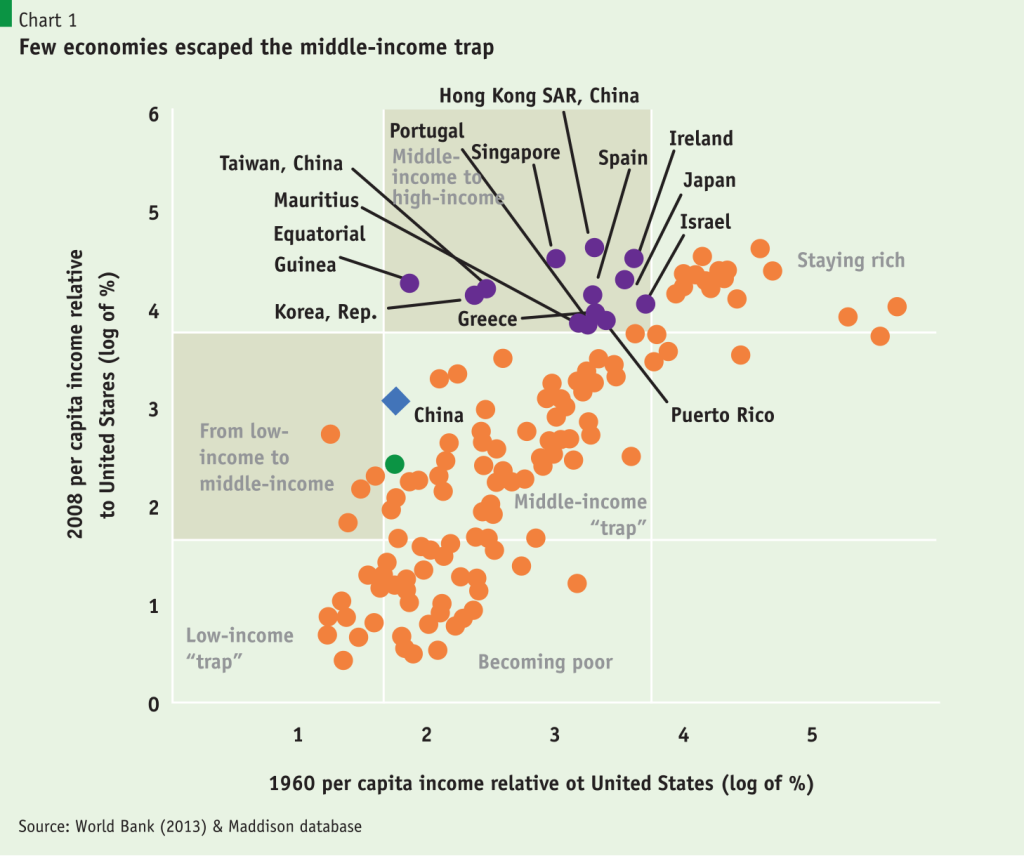

Most of the research literature defines higher-income economies as relative to the United States, as done in the diagram below. Approximately 40% of the U.S.’s per capita income, or USD 25,000 to USD 30,000, is the threshold for becoming a high-income country.

As the Chart 1 shows, in the 48 years between 1960 and 2008, only 15 middle-income countries (in the middle of the top row) managed to become high-income countries measured by the increase in their income relative to the United States in purchasing power parity dollars2. Looking at the middle cell below the top cell – labelled Middle-Income ‘trap’ – one can find many countries with a similar position in 1960 as these successful 15 that could not grow into a high-income economy.

The middle-income trap has persisted. In the last few years until 2019, several upper-middle-income countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Venezuela, and Equatorial Guinea have made U-turns: their per capita income declined not only relative to the U.S. but also absolutely.

Where is Bangladesh in this chart? There is no reliable data for Bangladesh in 1960 in PPP dollars. Given that in 1960, Bangladesh was at approximately the same per capita income as the People’s Republic of China, and Bangladesh’s per capita income in PPP dollars is available for 2022, we locate that as the green dot below and slightly left of China. By this measure, Bangladesh has started its middle-income journey.

Another more straightforward and inclusive is the World Bank’s definition of high-income countries measured in per capita income to be between USD 12,000 and USD 12,700 in current prices for the past ten years. In either case, the results are similarly forbidding. In the past 33 years, for which the World Bank has data and classification benchmarks, only 21 countries have crossed from middle-income to high-income countries. However, most of these countries were island states that prospered in tourism booms, city-states, and members of the European Union, such as Portugal. Only four countries that did not belong to these groups during this period – Chile, Uruguay, South Korea, and oil-rich Oman – managed to become high-income.

Why does growth slow down in middle-income countries? Because sustaining economic growth at that higher stage requires robust institutions, knowledge, innovation, and research. Institutions need to secure human and property rights, not only from the state but also from powerful oligarchies. Preventing excessive economic inequality and elite capture of the state, which often go hand in hand, is also needed. It is worth noting that Chile, one of the three breakthrough countries that graduated into the high-income category, did so in 2012, well after the overthrow of military dictator Pinochet and the restoration of electoral democracy.

How is this relevant for Bangladesh, whose current per capita income is about USD 2,800 or almost 7,400 in PPP dollars? It is relevant because, as the bottom row of the diagram above suggests, income traps may exist at lower per capita income levels. A look at the evidence for some of the countries discussed above also shows a pause in growth when their per capita incomes were between USD 3,000 and USD 5,000. Much of that took place in the 1990s when, as today, these countries were dealing with exchange rate volatility, fragile financial sectors, the Asian financial crisis, and internal structural problems, including the dominance of oligarchies and crony capitalists.

As it happens, such a scenario faces Bangladesh today. After a record of solid macroeconomic management, Bangladesh is approaching a similar range of per capita incomes, also in a comparable period of turbulence and some similar features. Having embarked on our middle-income development journey, we must improve our economic management using technical expertise, research, and critical discussions.

Having embarked on our middle-income development journey, we must improve our economic management using technical expertise, research, and critical discussions.

Let us now turn to three sets of challenges facing Bangladesh as it starts its middle-income journey. Notably, these challenges will become opportunities if Bangladesh can successfully meet them. They will turn into sources for sustained long-term growth.

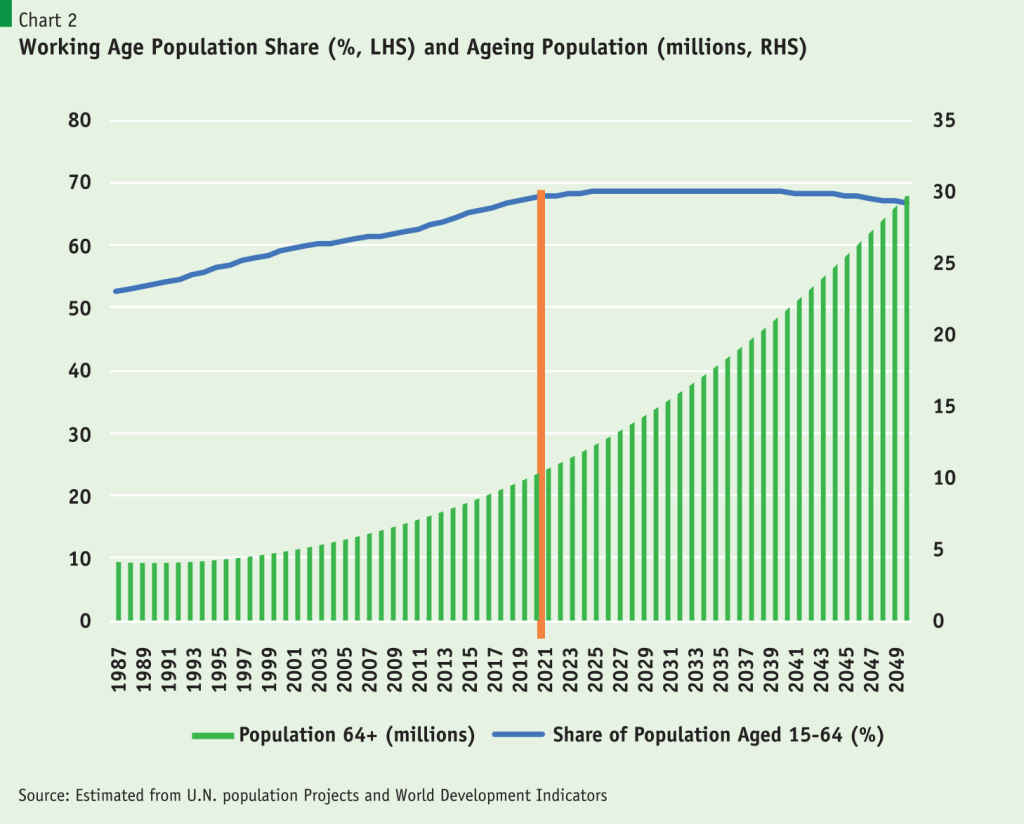

The Challenge of the Demographic Dividend: The issue is whether it will be a dividend or a disaster. Bangladesh has a young population: more than a quarter are below the age of 16, and since 2017, more than two-thirds of Bangladesh’s people have been working age (16 years to 64 years). U.N. projections in the diagram below forecast the share of the working-age population to peak at around 2033 at about 69%, but the two-one ratio will persist until about 2050. Thus, for the next 27 years, there will be two working-age persons for every dependent child or older person. The challenge is to boost long-term growth by productively employing this youth. On the other hand, if they are engaged in low-skilled jobs or unemployed, then there will be stagnation in society and social unrest, similar to the situation in countries in Africa, the Middle East, and South America caught in the middle-income trap.

Labour market survey data suggests Bangladesh has been struggling to cope with the employment challenge in recent years. While the slowdown in manufacturing employment growth has been known for a while, the preliminary result of the 2022 labour force survey shows that there have been dramatic job losses in industry and a sharp slowdown in urban job growth in the past five years.

A second issue in the diagram above is the rise in the ageing population from 10 million people to 30 million by 2050. That will mean a steep increase in pension and health care costs that will have to be provided.

Using the Demographic Dividend – Education Quality and Technical Training: A related challenge here is education. Bangladesh has made good progress in providing equitable access to school education. Net enrollment rates in primary education are in the high 90% with full gender equality. Overall, school years have increased to nearly 11 years. However, education quality has become a challenge. According to the 2017 National Student Assessment of Class 5 students, only 12% had grade-level competency in Bengali and 18% in Mathematics. In the World Bank’s harmonised test score data for countries, Bangladesh ranks 123rd among the 158 countries in the data set, while its competitors Vietnam and Cambodia rank 26th and 57th, respectively. Another issue here is the neglect of technical and vocational education, where the training of skilled workers is not only highly inadequate but the quality of training provided is uneven and unable to meet the needs of employers, as witnessed in the October Job Fair in Rajshahi where many companies could not fill their vacancies.

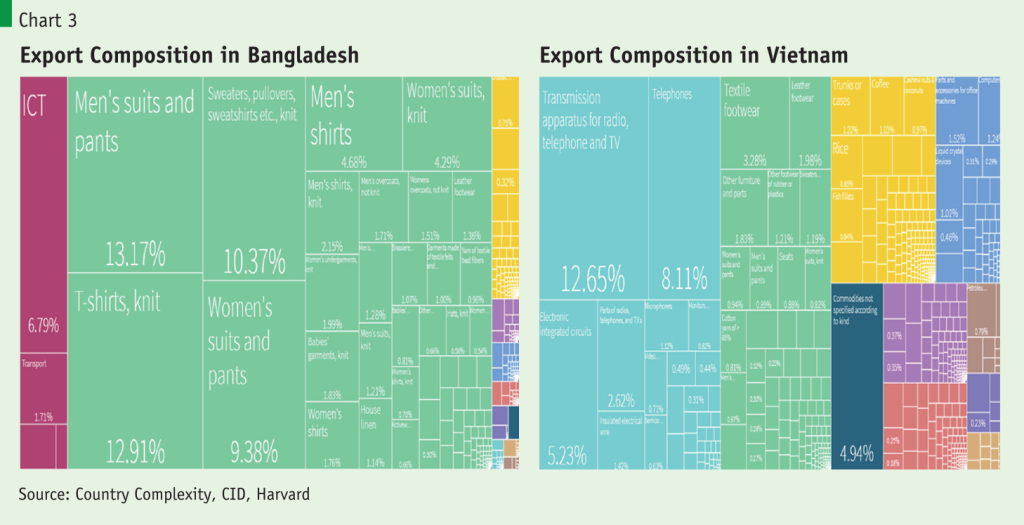

The Challenge of Providing Jobs – Economic Diversification and Foreign Direct Investment: How can good manufacturing and service jobs be provided? Sustained productive employment for Bangladesh’s rapidly growing 70 million labour force can only be provided by making the economy globally competitive. The critical constraint here is inadequate investment in diversified and competitive export sectors. Although Bangladesh exports more than 1400 items, most have remained incipient. Ready-made garments still constitute over 80% of Bangladesh’s exports (See figure below).

By comparison, Vietnam, a similar country and Bangladesh’s near competitor, exported USD 458 billion in 2022, of which less than 10% was in garments. Instead, it exported USD 187 billion in electronics and electrical appliances, USD 40 billion in computer equipment and USD 33 billion in leather. Worth stressing here is that Bangladesh’s RMG export prospects will be under pressure when Bangladesh graduates into the U.N.’s ‘Developing Country’ status a few years from now and loses all its tariff preferences by the end of the decade. Hence, increasing productivity, even in the RMG sector, has become a paramount necessity.

How can Bangladesh shift to more diversified exports and increase overall productivity? We will turn to several factors later, but the critical constraint is the marked absence of export-oriented foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2019, in the pre-COVID period, the total stock of FDI was just short of USD 20 billion while it was eight times larger, USD 160 billion in Vietnam. FDI brings not only capital for investment. The technology, knowledge, market access, and linkages to supply chains are as important as the capital.

Because of the absence of a supportive investment climate and regulatory framework, Bangladesh has been unable to attract export-oriented foreign direct investment. The critical point here is to attract export-oriented investment.

Bangladesh currently has extraordinarily high tariff and protection rates. Bangladesh’s overall nominal protection rate – including supplementary duties, is twice the rate of India and thrice that of Vietnam and Thailand. Hence, the rates of returns for manufacturing for the domestic economy are markedly higher than that for exports.

However, because the global economy is much larger, it necessarily means the employment a domestic market-oriented sector can provide will be far less than it would be for export-oriented industries. A telling example comes from the electronic home appliances sector, where domestic manufacturing, such as television, is expanding with nearly 100% protection in some cases. The current sales of the dominant firm in the home appliances sector, which has an 80% market share, is just over USD 1 billion, a drop in the ocean compared to the global market of USD 500 billion. If our home appliances manufacturing sector could be made export-oriented in the same way as our ready-made garment sector or as the home appliances sectors of East Asian economies such as Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia, the prospects for growth and job creation in Bangladesh would be vastly larger.

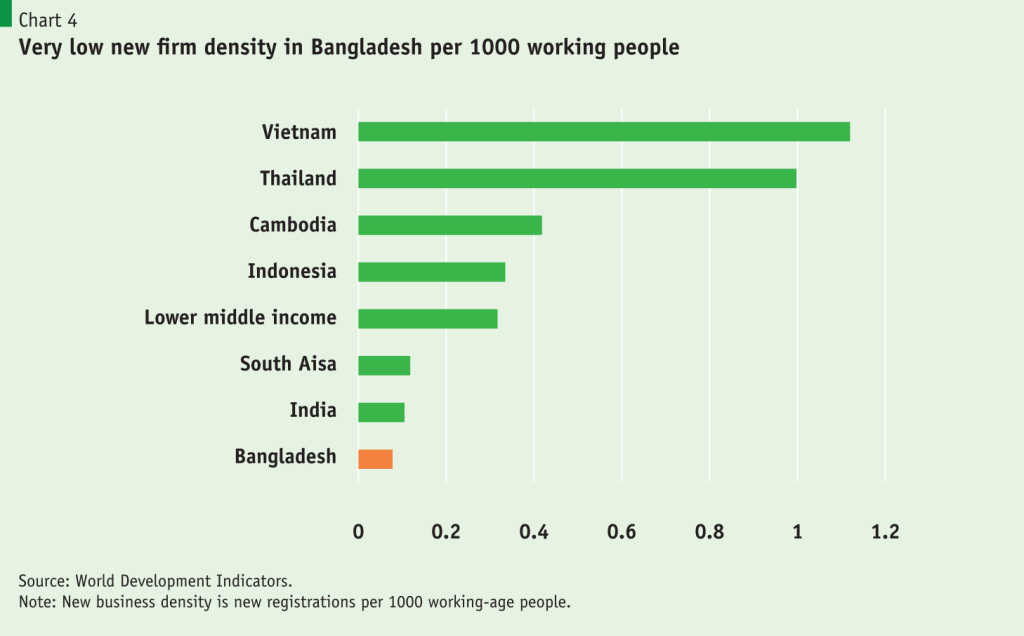

One impact of this inward orientation of the current manufacturing regime is the growing market dominance of the few firms. As a result, the churning and entry of new industries that are the hallmarks of a dynamic economy are absent in Bangladesh. International surveys show that new business entry per 1000 people in Bangladesh is only one-tenth that of Vietnam or Thailand, one-fourth that of Cambodia, and one-third that of lower-middle-income countries’ average. When market dominance by firms is as high as in Bangladesh, the high-profit margins from such market power create disincentives for these firms to become globally competitive and export-oriented. Job growth will remain limited in such a scenario.

A closely related issue here is the dysfunctionality of the financial sector of Bangladesh. The financial sector is the nerve centre of modern economies as it mobilises and allocates savings and capital to the most productive sectors. The financial sector in Bangladesh is both shallow and unstable. The summary indicator here is that private sector credit to GDP at 48%, is the lowest among middle-income economies. Comparatively, Vietnam has a private credit to GDP ratio of 126%.

Bangladesh’s financial sector’s shallowness is further compounded because more than 10%–15% of loans are non performing. Effectively, it means private credit flows are about 40% of GDP. Moreover, the high rates of nonperforming loans lead to constraints such as liquidity crunch and the lack of investor confidence in the economy, which are potential sources of macroeconomic instability.

Another critical challenge for growth and employment prospects in Bangladesh – which has surfaced only recently after the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, is finding energy sources. Over the past decade, in the wake of declining gas production, Bangladesh has taken the much more expensive LNG import strategy instead of investing in exploring and drilling. At present, estimated reserves of 10 or 11 Tcf are expected to be available for drilling and consumption against our current demand of 1 Tcf per year. But going further, several respectable studies have pointed to anywhere between 30 to 40 Tcf of probable reserves that will require exploration. At a more advanced phase, also waiting is the exploration of the Bay of Bengal, where India and Myanmar have discovered considerable gas reserves from their maritime areas adjacent to Bangladesh.

Another critical challenge for growth and employment prospects in Bangladesh – which has surfaced only recently after the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, is finding energy sources.

The Challenge of Building State Capacity and Institutions: The overarching challenge for long-term development is building institutions and norms that can provide public services and goods – whose benefits are jointly shared by many, such as clean air, water, better education and health, public transport, cities, and towns. Because of their shared nature, markets will not deliver these services on their own. In building institutions, transparency, accountability, and contestability in the Government’s executive, legislative, and judicial branches will need strengthening. Governments will have to be brought closer to the people through decentralisation. Further, Bangladesh has to build institutions that not only use expertise but also encourage critical discussions. Otherwise, there will be no course corrections for inevitable policy mistakes.

The overarching challenge for long-term development is building institutions and norms that can provide public services and goods – whose benefits are jointly shared by many, such as clean air, water, better education and health, public transport, cities, and towns.

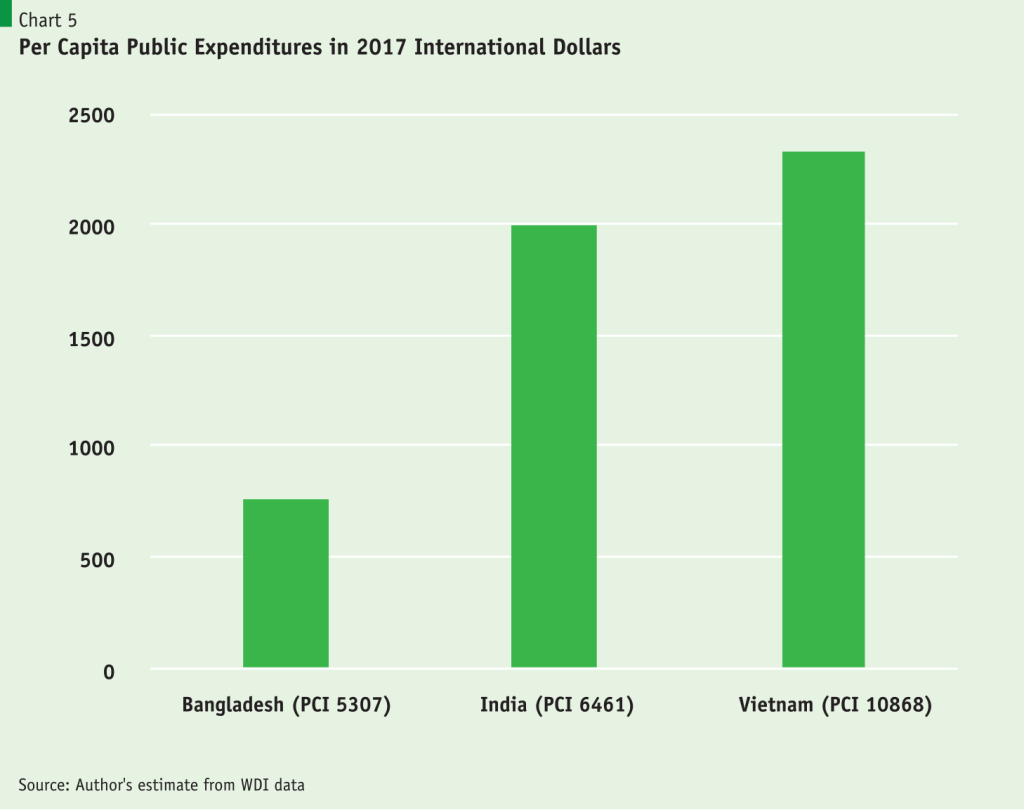

Let us specify using three examples. Bangladesh’s first task here will be raising revenues and increasing public expenditures. Bangladesh’s revenue collection of about 8%–9% of GDP ranks in the bottom 10% of countries. One consequence is that our public expenditures are highly inadequate, as shown in the figure below. Our per-capita public expenditures in comparable international dollars is about one-third that of India and one-fourth of Vietnam’s. Public expenditures in human capital are woefully below international norms. There is also the need to ensure that our public expenditures are effective where much attention is needed, as noted below.

A second broader task is to strengthen our weak and eroding economic management capacity. This wide-ranging matter affects many institutions, such as the Ministry of Finance, the National Board of Revenue, the Ministry of Planning, the Bangladesh Bank, and regulatory bodies. But the critical issue here is the need to invest in implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, and more broadly, in data. Bangladesh invests staggeringly little in these matters: about 0.1% of the Annual development budget is spent on its monitoring and evaluation. Not surprisingly, project implementation suffers. Equally alarmingly, we expend only 0.05% of our GDP in gathering data on our increasingly complex 460 billion-dollar economy (in 2022 exchange rates). Data collection is thus poor and delayed. Policymakers have to make decisions blindly, looking at the rearview mirror.

Third, the challenge will be to make our governing institutions more accountable, transparent, and closer to the people. By that, we mean moving away from the highly centralised public service delivery system where the central government spends about 92% of all government expenditures. In contrast, 900 other city, municipal, and upazila governments, including Dhaka, formally have wide-ranging responsibilities for public services and basic infrastructure and have less than 10% of the national budget for their use. The big agenda here is to develop high-quality urban centres that house and provide residents with public services and higher productivity jobs. That will be an essential requirement for raising overall economic productivity. Unless town and city governments are empowered and made accountable by providing them resources through taxation powers, shared revenues, and the capacity to coordinate urban activities well, such transformations will not be possible. In that event, Bangladesh will be in a lower middle-income country trap.