The Challenge of Export Diversification

By

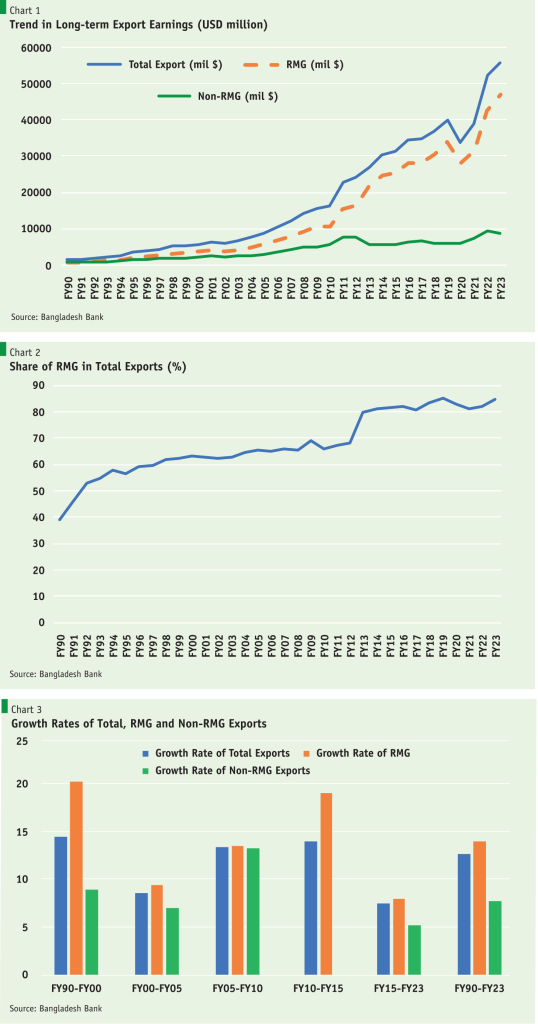

Bangladesh has secured outstanding long-term export performance, growing from a mere USD 1.5 billion in FY1990 to an astounding USD 55.6 billion in FY2023 (Chart 1). On average, exports grew by an amazing 12.7% per year over a 33-year period, which makes Bangladesh one of the fastest growing export countries. This export-orientation of the development strategy has served Bangladesh well, contributing handsomely to GDP growth, employment and poverty reduction. Moving forward, the main development challenge for Bangladesh is to preserve this superb export performance as it seeks to climb up from a lower-middle income country status, as defined by the World Bank, to an upper-middle income country by 2031.

While the long-term highly favorable export trend is good news and speaks well to the Bangladesh potential, over the past 18 months or so the economy is facing some severe headwinds that are threatening to derail this long-term progress with export performance. These headwinds have been cumulating over the past several years, although they gathered force in the wake of the 2022 global inflation and the Ukraine War. Imports have surged, growth of exports has slowed, and foreign exchange shortage has mounted. Import and exchange controls are being used to manage the shortage of foreign exchange. The reduction in imports is deep and has tended to hurt both investments and GDP growth. The push for higher growth of exports has become critical to restore the momentum for investment and GDP growth.

A review of Chart 1 tells the clear story of the domination of ready-made garments (RMG) in the export basket. Not only that RMG has led the way to the remarkable expansion of exports in Bangladesh, but its domination has also rapidly expanded and has continued to do so (Chart 2). Thus, the share of RMG in total exports has surged from a low of 46% in FY1990 to a high of 85% in FY2023.

Except for a brief period from FY2005–FY2010, non-RMG exports have generally performed sluggishly. Compared with 14% annual growth of RMG exports between FY1990 and FY2023, non-RMG exports grew by 7.7%. More importantly, the average growth of non-RMG exports is falling over the years (Chart 3). The decline has been pretty sharp in recent years when the average growth of non-RMG exports slumped to only 5.2% between FY2015 and FY2023.

The heavy concentration of the Bangladesh export basket on one commodity group and the associated absence of export diversification has posed a major challenge for strengthening export performance. While the global RMG market is very large and Bangladesh has scope for increasing its market share, as it has been doing in the past, excessive concentration on RMG faces several risks.

The heavy concentration of the Bangladesh export basket on one commodity group and the associated absence of export diversification has posed a major challenge for strengthening export performance.

First, Bangladesh has benefited heavily from the trade concessions granted by the European Union (EU) and others as a Least Developed Country (LDC) under UN classification. It is now slated to graduate from the LDC status by 2026. The loss of trade preferences, especially the duty free-quota free (DFQF) access to EU markets, would hurt the growth of RMG exports.

Second, stiff competition from Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Turkey, Latin American countries, Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan could dampen RMG export growth prospects for Bangladesh. Regional Free Trade Agreements of competing countries with USA and EU could further hurt Bangladesh RMG export growth.

Third, global demand for RMG is subject to many uncertainties including slowdown in income growth, buyer domestic policy requirements and political imperatives. Any unanticipated shock to the global RMG market could easily derail Bangladesh export performance.

Fourth, the recent balance of payments developments show that exports need to grow much faster than the present rate of 7% to avert the growing pressure on the exchange rate. Without the expansion of non-RMG exports, which recorded a massive reduction of 9% in FY2023, the prospects of achieving double-digit growth in exports are doubtful.

Finally, the RMG sector in Bangladesh is undergoing technological transformation that is causing growing automation and rising capital intensity. As a result, the job creation potential of RMG has literally vanished. Without the expansion of a labor intensive diversified non-RMG manufacturing base and exports, the job creation prospects of the Bangladesh economy are dim.

The imperative for export diversification is obvious and has been well-known to Bangladesh for the past several years. Yet the performance of non-RMG exports show that nothing effective has been done to diversify the export base. Research done at the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI) shows that in FY2021 Bangladesh exported some 1393 non-RMG products, of which 346 items registered export values of USD 1 million or above. Among these, Bangladesh has strong comparative advantage in 39% of the products and moderate comparative advantage in another 27% of the products. So, potential competitiveness of a large, diversified export basket is not an issue.

The reason that this potential has not materialised in actual sustained export growth for most of the products is because of the large anti-export bias of government policy, especially related to trade policy and the exchange rate. On the trade policy front, there is huge protection accorded to import substitutes through a range of tariffs and para-tariffs that make production for the domestic market much more attractive than exports. Fortunately, RMG exports are insulated because of enclave benefits such as duty-free access to imports through the Special Bonded Warehouse (SBW) scheme. But non-RMG exports do not have this benefit. As a result, the non-RMG export initiatives mostly fizzle out and investors flock to production for the domestic market.

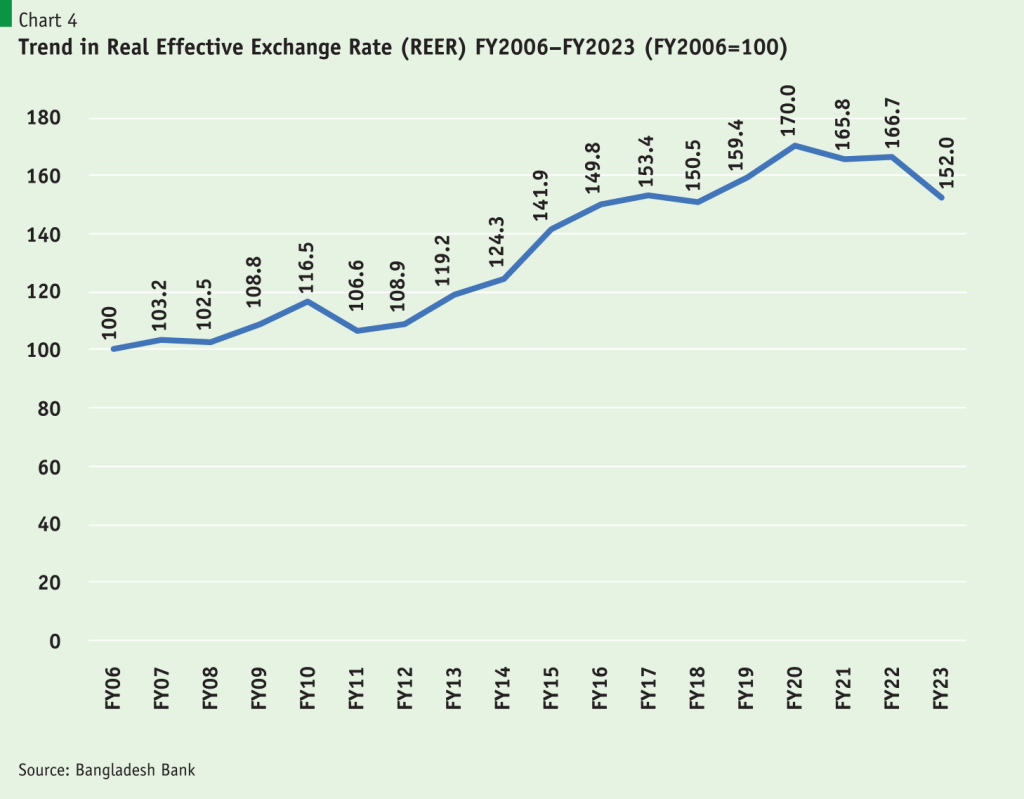

Regarding the exchange rate, Bangladesh managed its exchange rate flexibly and kept it competitive for the periods FY1990–FY2006. But between FY2006–FY2022, there was a sharp appreciation of the real effective exchange rate (REER). The REER appreciated 67%, which badly hurt exports (Chart 4). The adverse effect was particularly harsh for non-RMG exports, which grew by a mere 5.2% during FY2015–FY2023. There has been a welcome correction of this in FY2023; the REER depreciated by 9% between June 2022 and June 2023. Even so, the REER remains appreciated by 52% as compared with the level in FY2006. Clearly, the management of the exchange rate has been hurting exports for a fairly long time.

Additionally, while RMG exports have access to several other benefits related to concessional finance, special subsidies and tax incentives, most other non-RMG exports do not have similar benefits.

Effective management of the export diversification challenge will require concerted policy actions on several fronts. The government’s recent decision to free up the exchange rate to market forces is a smart move, although its implementation is still open to debate. But unfortunately nothing significant has been done to eliminate the anti-export bias of trade policy. Without appropriate tariff reform that minimises trade protection, there is very little hope of diversifying the export basket.

Export diversification will also require additional efforts to strengthen market access through Free Trade Agreements, comply with safety and environmental regulations, improve trade logistics through deregulation and investments in port and transport networks, promote export oriented FDI by lowering the cost of doing business, and strengthen labor skills through investment in education and training. This is a medium-term agenda, but concerted actions are needed now, especially by fast-tracking the reform of the trade policy regime for imports.