Macroeconomic Challenges and Policy Options in Bangladesh

By

Background

Bangladesh economy is facing multiple challenges on the macroeconomic front: inflation is running high with negative impacts on the standard of living of most of the households; balance of payments imbalances are creating tensions in the exchange market; and government interventions to stabilise the exchange rate have contributed to a rapid loss of reserves. The balance of payments (BOP) imbalances resulting from supply disruptions in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, the commodity price shocks at the outbreak of the Ukraine-Russia war and inadequate domestic policy response. The difficult BOP situation has been manifested through

- rapidly declining foreign exchange reserves of Bangladesh Bank (Chart 1);

- a sharp depreciation of Bangladesh Taka against the US dollar and other major currencies; and

- a surge in inflation as measured by the increase in the consumer price index (Chart 2)

The decline in foreign exchange reserves is a major concern since it has contributed to a sharp depreciation of the exchange rate and also contributed to the surge in domestic inflation. After a long period of exchange rate stability, the exchange market has become unstable initially due to post-pandemic supply side disruptions and Ukraine-Russia war. But subsequently the problem continued due to domestic issues.

The decline in foreign exchange reserves is a major concern since it has contributed to a sharp depreciation of the exchange rate and also contributed to the surge in domestic inflation.

After remaining fairly stable in the 6%–7% range, inflation started to surge since 2022, and still remains high at close to 10% level. While the surge in inflation was broad-based, food inflation surged to 12% contributing to the price pressure.

The Problems Facing Bangladesh Originated over a Long Time and from Multiple Sources

Although the Terms of Trade shocks resulting from Post Pandemic supply side disruptions and the Russia-Ukraine war sharply deteriorated the BOP situation, Bangladesh’s macroeconomic management has also been complicated by a number of domestic economic policies and developments. These include:

- Maintaining a fixed interest rate regime (9%–6%) for a long time despite the rapidly changing global economic and financial environment.

- Maintaining a virtually fixed exchange rate (ER) regime for more than a decade despite high inflation compared with trading partners and competitors.

- Very low tax/GDP ratio and its declining trend. Bangladesh has the lowest tax/GDP ratio among its comparator countries.

- A very shallow financial system along with significant weakening of the banking system.

In response, Bangladesh Bank for a long time only hoped for a positive supply response to fight inflation. The fixed interest rate policy (9%–6%) was the only monetary policy that Bangladesh Bank followed in recent years. Inflation fight remained unattended since, after fixing the interest rates, Bangladesh Bank could not have any other monetary policy instrument to influence the inflation outcome. At the same time, in addition to the liquidity support provided at the time of the pandemic, BB printed massive amounts of high-powered money in FY2023 to finance budgetary spending. Liquidity support for banks facing withdrawal of funds and other special BB financing schemes also injected liquidity into the economy. The Net Domestic Asset (NDA) of BB more than doubled in FY2023, implying that the NDA expansion in one year was more than the cumulative NDA expansion of BB over the last 50 years since independence. There was a complete disregard for inflation fight from a central bank perspective, relying on the hope that an improved domestic supply situation will help contain inflation.

There were serious and persistent structural problems in the external sector. A review of the external sector developments indicates serious structural problems and policy lapses. Some of the structural problems include:

- Concentration of export products—with readymade garments (RMG) accounting for 84% of total export receipts. The share of non-RMG exports is slowly but surely declining over time despite talks about export diversification over many years.

- Concentration of export markets—Bangladesh exports are mostly concentrated in the developed western economies like the European Union, Canada and the USA.

- Stagnation of inflow of workers remittances and very low per capita inflow of workers’ remittances due to high share of unskilled workers. The number of workers going abroad has been increasing rapidly in the post-covid period, but due to capital flight through Hundi operations and the low-income level of Bangladeshi unskilled workers the inflow of remittances have remained low.

- Service sector deficit due to very limited service sector exports but large sums of service related payments on account of health, education, tourism, shipping, insurance and higher finance charges due to weak financial system and economic vulnerabilities.

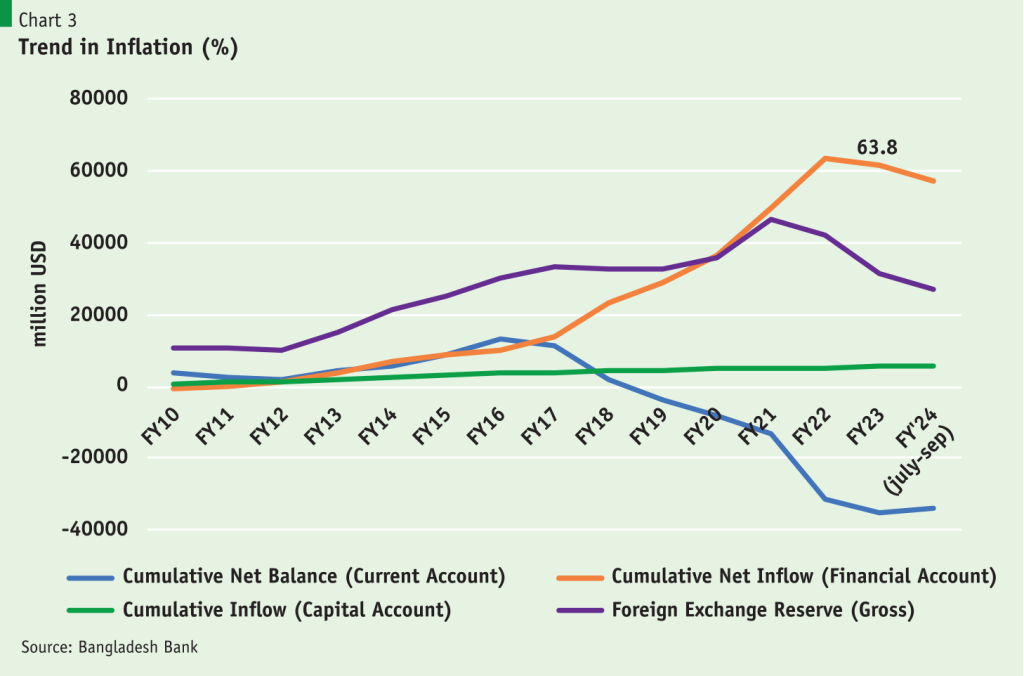

A new development is that, silently Bangladesh has become dependent on financial account flows. In our usual discourse on BOP developments, we generally focused on the external current account balance and the contributing factors like developments in exports, remittances and import payments. While on a cumulative basis the current account balance (CAB) was positive until FY2016, thereafter it turned negative and the cumulative CAB turned to negative USD 35 billion by FY2023 from a cumulative surplus position of USD 12.9 billion in FY2016.

In contrast, the cumulative financial account (net) (FA) surplus sharply increased to USD 63.8 billion in FY2022, before it started to reverse starting from FY2023. When we examine the buildup of reserves, it is interesting to observe that until FY2016, both CA and FA surpluses contributed to the growth of reserves. The situation changed thereafter as the CAB turned negative but reserves continued to increase supported only by the continued surge in FA surplus.

Managing Financial Account is thus a Major Challenge for Bangladesh—but are We Ready?

There is nothing wrong with Bangladesh experiencing higher inflows through the financial account in recent years. Most dynamic emerging economies including India, Vietnam, Thailand and others have high financial account inflows. Attracting and managing financial account flows require proactive management of interest rates, containing the inflows if too much hot money is coming to complicate domestic monetary management, avoid fixing the exchange rate for a long time, keeping the domestic currency attractive through higher interest rates and by containing inflation and making the investment climate attractive.

A strong financial sector is a major attraction for the foreign portfolio and private capital investors. In particular foreign portfolio investors like to invest in good companies in the stock market, they want to invest in domestic bond and securities markets and in banks and companies with good governance structure. We must keep in mind that mismanagement of financial accounts and the resulting capital outflows were the main contributing factors for the Asian Crisis of the 1990s. Those economies also kept their ERs virtually fixed, like Bangladesh, for a prolonged period prior to the Asian crisis.

The fixed exchange rate regime for almost one decade until FY2023 and the policy of ultra-low global interest rates contributed to carry trade. Carry trade is a globally observed phenomenon under which domestic entities borrow in foreign currency at cheaper interest rates to save interest costs. This phenomenon is more encouraged when domestic interest rates are virtually fixed. The policy of fixed ER in Bangladesh coupled with an environment of ultra-low interest rates globally, created incentives for the domestic firms to borrow in foreign currency without regard to the potential ER risk. The surge in private sector foreign debt to almost USD 26 billion was a manifestation of this ‘carry trade’ phenomenon. Private borrowers were lured by low interest rates on foreign debt coupled with the virtually fixed ER regime of that time.

The sudden ER depreciation of more than 32%–45% in the ER rate has increased the liabilities of the corporate sector by almost BDT 1.0 trillion, for which the companies had to take additional provisions and losses of this magnitude eroding the corporate sector profitability. As the private sector lost its interest in foreign borrowing, inflows stopped and outwards payments pressure increased leading to loss of reserves and accumulation of unsettled foreign payments. The improvement in the CAB, primarily through import compression, is important but could not reverse the loss of reserves. The outstanding USD 12 billion of short-term debt is a sword hanging over Bangladesh.

Low Tax Collection is a Major Drag and the Ultimate Source of Major Problems in Bangladesh

Low level of domestic resource mobilisation coupled with other structural problems have diminished the government’s capacity to cope with the macroeconomic challenges and meet the political aspirations of the government. Some stylized facts presented below indicate the extent of the problem and the structural challenges facing Bangladesh on the revenue front.

Low level of domestic resource mobilisation coupled with other structural problems have diminished the government’s capacity to cope with the macroeconomic challenges and meet the political aspirations of the government.

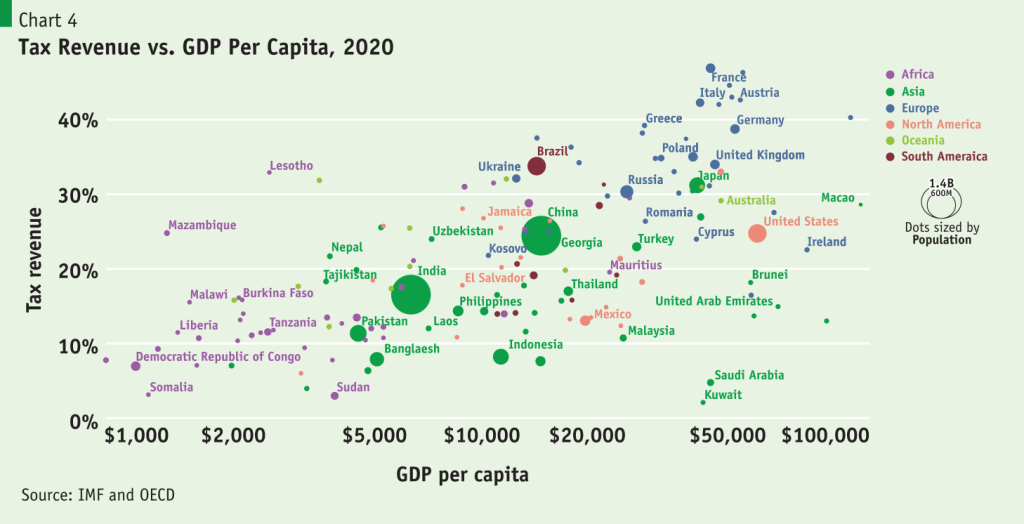

For its per capita income level Bangladesh has one of the lowest tax/GDP ratios globally. Generally, it is expected that tax/GDP ratio increases in a country in line with increase in per capita income. Bangladesh, despite being close to India in per capita income terms, has much lower tax/GDP ratio. Despite being much higher per capita income, Bangladesh’s tax/GDP ratio is lower than Pakistan. European countries generally have much higher tax/GDP ratio—higher than 40% in France, Austria, Italy; and Germany, Greece, Poland and the UK in the 35%–40% range.

Where Bangladesh Stands in a Global Context

Furthermore, Bangladesh’s tax /GDP ratio has stalled or declined since 2012. In the early years, 1984–1994, Bangladesh’s per capita income did not increase much, but the tax/GDP ratio almost doubled to 7%. Since 2001, per capita income started to increase along with the increase in the tax/GDP ratio. The ratio crossed the 9% level in 2012 when per capita income reached USD 1000 level. After 2012, the line became almost vertical, indicating that despite acceleration in per capita income the tax/GDP ratio was stagnant around 9% of GDP.

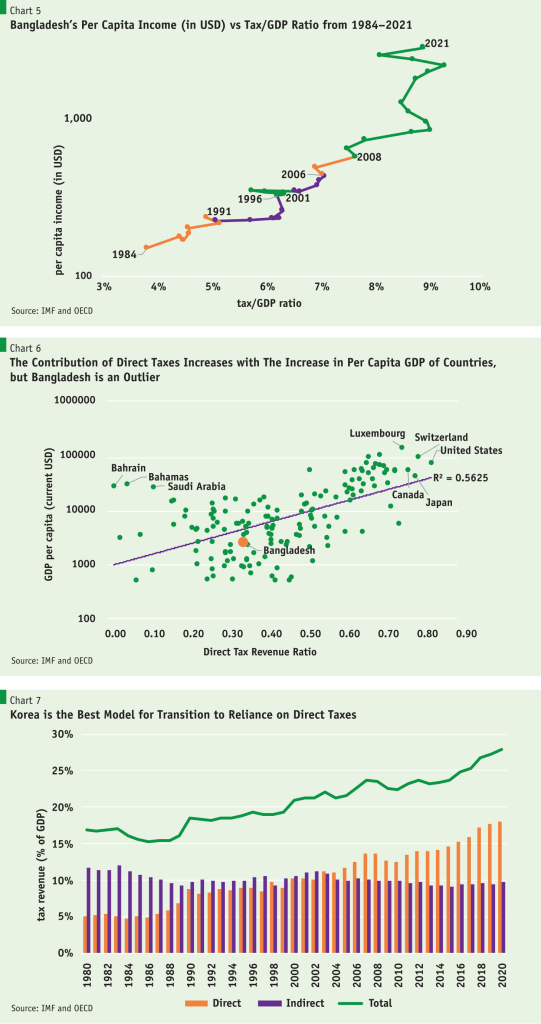

Lack of buoyancy in the direct tax system is one of the major contributing factors behind the poor tax/GDP ratio. The observed global phenomenon is that the ratio of direct taxes in total tax revenue or dependence on direct tax increases with the increase in per capita GDP. The best performer in collecting direct taxes is the USA where more than 85% of the total tax revenue comes from direct taxes. At about 35%, the share of direct taxes in total taxes for Bangladesh is very unsatisfactory and Bangladesh direct tax administration has a long way to go.

This phenomenon of increasing dependence on direct taxes is observed in almost all regional countries like India, China, Korea and Thailand. In all these regional countries, the share of direct tax increases over time with the increase in per capita GDP. Bangladesh is an exception. Thus, future reform thrust at NBR should be more on direct taxes. Bangladesh cannot sustain its development objectives given its very low tax/GDP ratio. The size of the government is already very small, about 13%–15% of GDP and further declining in relation to GDP. Bangladesh cannot achieve its cherished high-middle status by 2031 and high-income country status by 2041, given its current very low level of domestic revenue mobilisation.

While most emerging economies have increased their reliance on direct taxes over time in line with the increase in per capita GDP, the case of Korea is especially worth mentioning. Korea’s drive for higher tax/GDP ratio over the years, has been entirely on account of the steady increase in the share of direct taxes. The key lesson from the regional countries including Korea is that the importance of direct taxes must be underscored in future tax reform.

The reform agenda for revenue mobilisation must be broad based and encompass administrative and tax policy issues. Despite the secular decline in the tax/GDP ratio over more than one decade, there was no political pressure for bringing about the necessary changes. Now this has come to the point that it cannot wait anymore. Government is suffering from liquidity shortages in both foreign and domestic currency. It is borrowing heavily from both external and domestic sources to finance the budget deficit. The debt/GDP ratio may still look favourable in a conventional sense, but in terms of capacity to service debt—measured more appropriately in terms of debt/revenue ratio—Bangladesh’s debt burden is one of the highest in the world. Bangladesh once was considered to be HIPC countries (based on IMF criteria) because of its debt/revenue ratio close to 400%, a threshold for HIPC eligibility.

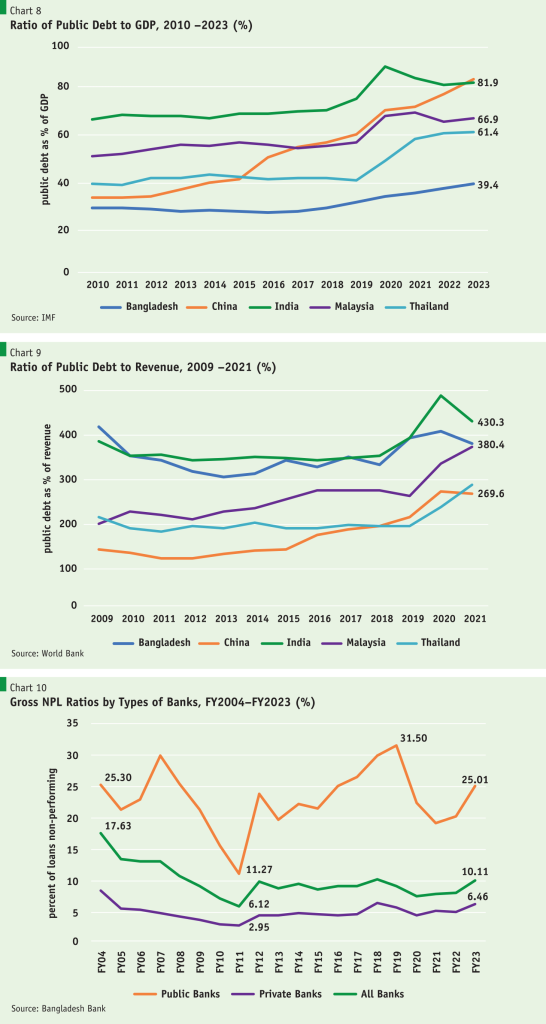

At 39.4% of GDP, Bangladesh government’s debt/GDP ratio is one of the lowest among the comparator countries. But Bangladesh government’s very poor revenue performance makes its debt burden excessive when expressed in terms of its capacity to pay measured in terms of debt/revenue ratio. The two Charts below (Charts 8 and 9), indicate the vastly different conclusions that could be derived from the two ways of presenting the debt burden for a country. While Bangladesh’s debt/GDP ratio is less than half of India and China, in terms of capacity to pay—measured in terms of debt/revenue ratio—Bangladesh’s burden is much higher than China and close to that of India.

The agenda for reforms are well understood and there is no need for going into details. We should simply underscore that the focus should be on fundamental tax administration and policy reforms, with emphasis on international best practices and automation.

Financial Sector is the Other Major Area Which Needs Massive Overhaul in the Post-Election Period

Financial sector in Bangladesh is in a very poor state and needs overhaul. Banking sector is the largest component and better managed part of the financial sector, but that is also in a very bad shape. Banking system is suffering from a huge burden of nonperforming loans, slowdown in deposit growth and low profitability. Some banks are also suffering from chronic liquidity crisis, but are being bailed out by Bangladesh Bank through frequent and large-scale liquidity support. The bailouts are happening without much accountability.

Banking system is suffering from a huge burden of nonperforming loans, slowdown in deposit growth and low profitability. Some banks are also suffering from chronic liquidity crisis, but are being bailed out by Bangladesh Bank through frequent and large-scale liquidity support. The bailouts are happening without much accountability.

The state of the banking sector is being demonstrated below:

The problem of non-performing loans is worsening. Following a period of steady decrease in non-performing loans due to the financial sector reform program initiated in early 2000s, the situation started to deteriorate after FY2011.NPLs of both public and private banks improved significantly until FY2011. Thereafter, with the deteriorating governance, the NPLs started to increase once again and exceeded more than 10% in FY2023. The true picture is much worse. After including the repeatedly rescheduled nonperforming loans and the loans stuck in the court system for a very long time, the actual level is believed to be about 25% of the outstanding total loans.

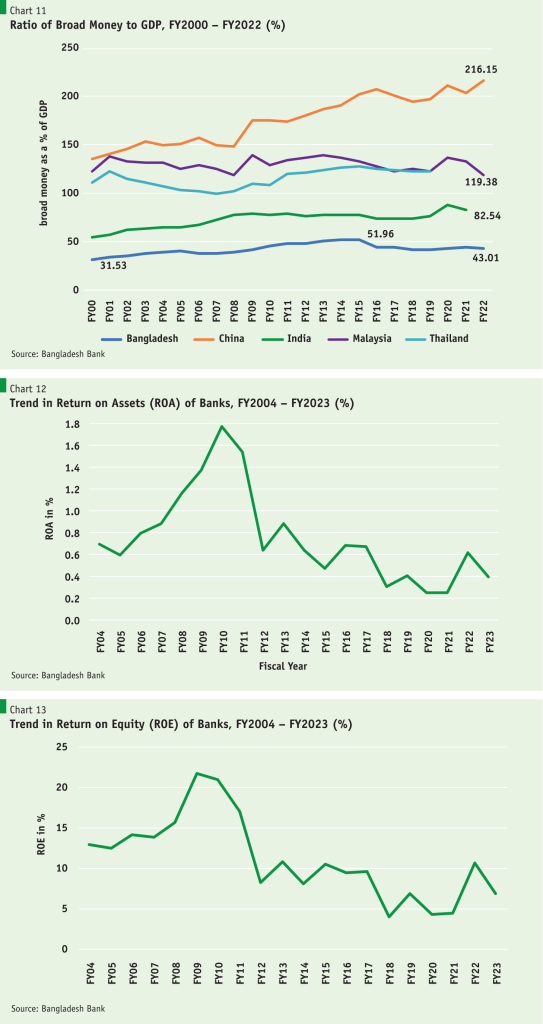

Bangladesh’s financial sector is extremely shallow. The depth of the financial sector may be measured in terms of the ratio of broad money (M2) over GDP. After increasing by 20 percentage points to 52% over the period FY2000–FY2015, the ratio started to decline in line with the general deterioration of the financial sector in Bangladesh (Chart 11). Currently at only 43%, the ratio is almost half of the level of India, and well below East Asian countries (more than 100%) and China (more than 200%).

Reflecting the poor performance of the banking system, the Return on Assets and Return on Equity of banks have deteriorated sharply in recent years. Both the ROI and ROE improved significantly following the reforms undertaken in the early 2000s. In the decade following the reforms the performance of the banking sector improved remarkably as reflected in the improvements in these two important indicators. The underlying improvement in the non-performing assets of the banking system and other systemic measures contributed to this outcome. However, the indicators started to reverse after FY2011, as the overall governance of the banking system deteriorated. The banking sector which is a major part of the stock market and contributes significantly to tax revenue due to its very high corporate tax rate at 40% and above, also fell behind in its contribution to domestic revenue with the decline in its profitability.

The rapid decline in the growth of savings at banks is troubling. Historically, Bangladesh banking system had enjoyed a buoyant growth in bank deposits ranging between 15%–20%, allowing the banking system to expand domestic lending at about similar rates. However, like many other indicators, deposit growth also steadily decelerated after FY2011 and reached its lowest point of 7.46% in FY2023. This very low deposit growth—a reflection of the withdrawal of liquidity through loss of foreign reserves associated with the BOP problem—seriously undermines the government’s ability to borrow from the domestic banking system to finance the budget deficit. The drop in bank deposits also reflects This decline in bank deposits also reflects a lack of confidence in banks and is also a result of the poor return on savings accounts for a long time due to the caps on the domestic interest rate structure under the ‘6%–9% Interest Cap’ policy. The prevailing high inflation rate also made savings in banks much less attractive with a negative real rate of return.

At a time when bank deposits are falling, the reliance of the budget on borrowing has been increasing (Chart 15). The proportion of expenditure covered by revenue has declined from almost 75% of total expenditure in FY2010 to 63%–65% range in recent years. This growing dependence on deficit financing is primarily attributable to the dismal revenue performance of the government as discussed earlier. At the same time, this higher borrowing pressure is happening when banks are experiencing a serious liquidity pressure. This combination of higher borrowing pressures and tightened liquidity is also complicating both monetary and fiscal management of the relevant authorities. This situation creates problems for budget financing, sometimes leading to money creation by the central bank and the consequent inflationary pressure as happened in FY2023.

Concluding Observations and Way Forward

Bangladesh is facing multiple challenges on the macroeconomic front. Bringing down inflation, restoring exchange rate stability, preserving and then rebuilding foreign exchange reserves to much higher levels and managing the fiscal situation despite revenue shortfalls will be extremely challenging. The short-term problems have also been compounded by the long-term structural problems associated with the structure of BOP, the extremely vulnerable banking sector, and the poor state of revenue administration.

Bangladesh Bank has been much slow in reacting to the emerging BOP problem—But must fix them. Bangladesh Bank took a long time to address the widening CA deficits, but the growing financial accounts inflows masked the underlying BOP problem until late in FY2022. The growing levels of reserves made BB complacent about the sustainability of its virtually fixed exchange rate regime. But the situation has changed and the government needs to work on several front to:

- get out of the current difficult BOP situation;

- prevent future problems by putting in place mechanisms for exchange market operations; and

- adopt an interest rate policy which is proactive, flexible and market based.

The Bangladesh government also needs to work out a plan for settling the payments liabilities. In addition to the short-term private sector debt of USD 12 billion, Bangladesh has many other unpaid liabilities which need to be quantified comprehensively. Right now, there is no comprehensive official picture that is publicly available. Some of the other overdue payments include payments to: energy sector companies believed to be more than USD 4 billion; and unknown but sizable amounts to the international airlines, fertiliser importers, overdue payments to settle LCs, and repatriation of profits and dividends by foreign companies. There is also a huge pent-up demand for imports, which could not be met due to shortage of dollars. The economy is already paying some of the costs: Fees/charges for LC settlement has gone up significantly; the rating agencies have downgraded Bangladesh and its economic and BOP outlook; airlines have increased their airfares in and out of Bangladesh by using much depreciated ER and some international airlines have reduced their flights to Bangladesh. The total amount, although unknown, may easily be close to the available reserves of Bangladesh Bank. Thus, paying all of these private creditors at this time is not a viable option. The authorities need to work out a comprehensive plan to settle these payments over the next several years and engage with the creditors in a constructive manner.

Restructuring the banking and the broader financial sector and improving the elasticity of the tax system will require comprehensive medium-term reform programs. International expertise and financial support from the multilateral organisations may help in preparing the right strategy and reducing the financing requirements through additional support under new programs. External technical and financial support were never problems in initiating reforms in these areas in the past, and will not be in future. But what is really needed is the political will to undertake real and not superficial reforms.

While not much can be done before the forthcoming national elections, preparations must be taken to roll out major reforms to ensure market-based interest rates, proper management of the exchange market to ensure unified market-based exchange rate along with exchange rate stability, and regularise or restructure the overdue payments to the international creditors. Notwithstanding the challenges, the situation can be stabilised and turned to a positive direction. However, for that to happen, the post-election political leadership of the economic team should be credible and with a strong political mandate. The current narrative of the government must change to prepare the public for some of the short-term difficulties and pains that are likely to be associated with any strong reform strategy. Business as usual is not an option.