Will Bangladesh’s Urbanisation Pattern Promote or Hinder Growth?

By

One of the most established findings in growth economics is that there is a robust relationship between urbanisation – the increasing share of population living in urban areas – and long-term growth. In short, as we will see below in Chart 1, without urbanisation, there is no long-term growth. However, more recent research has qualified this finding by stressing that without “good” or productive urbanisation, there can be no long-term growth. Good urbanisation provides opportunities for investment and more productive jobs for migrant workers from rural areas through higher demand, through the pull factor. Thereby, such a process provides higher income for workers, enables the structural transformation of the economy from agriculture to industry and services, and increases overall economic productivity, the source of long-term growth.

Economic theory and evidence have appreciated over the last few decades that without proper strategy, planning, and implementation, there can be unproductive or “bad” urbanization that hinders growth. As the overall population grows without opportunities for gainful employment in rural areas, people move to urban areas to work in the informal sector, living in poor conditions slums. Such urbanisation is driven by labor supply, not labor demand. That is, this is a “push-factor” urbanisation with only marginal gains in productivity. Due to the nature of urbanisation, the physical construction, form and changes in land use involved, such “bad” urbanisation can hinder growth because these changes are hard to reverse. This is called the putty-clay problem: what was malleable before these changes turn into unmalleable clay afterwards and traps the economy into a low-productivity equilibrium.

In this article – the first of a two article series – we discuss whether the pattern of urbanisation in Bangladesh is promoting growth or hindering growth. We present evidence that: (i) while Bangladesh’s past development was stimulated by robust, albeit not well planned, urban development, it is now facing the prospect of entering the second “bad” kind of urbanisation; (ii) As a result, urbanisation is slowing and as industry is moving out of urban areas to rural areas, job growth in urban areas have sharply decelerated; and (iii) And while there is the positive churning – new urban areas are emerging – the process has become diffused with urban development bypassing many secondary cities and towns and haphazardly becoming spread across the country. Such patterns will have an adverse impact on industrial development and jobs. Because such processes have strong network externalities and are driven by building and infrastructure construction, they are difficult to reverse. So, it has become an emergency now to build institutions and implement policies that create good urbanisation.

A.The Bangladesh Context

After making remarkable economic and social progress over the last few decades, especially after the restoration of democracy in 1991, Bangladesh is now facing the challenges of becoming a more complex middle-income economy. After achieving growth rates of above 6% p.a. in the 2010s, globally lauded improvements in health and education, and a market decline in poverty to 18% (from 44% in 1991), Bangladesh became a lower-middle-income economy and is about to graduate out of a least Developed Economy into a Developing economy as per the United Nations terminology. Success in raising food production, labor-intensive textiles exports and manufacturing, and employing Bangladeshi workers abroad were drivers of growth. So was the rapid urbanisation that increased the urban population by 10 times since independence.

In the past three years, however, the need to contain high current account and fiscal deficits and monetization has caused persistent high inflation, foreign exchange and domestic liquidity pressures and weakened balance sheets of firms, banks, and government. These economic problems are currently compounded by a complex political transition after the overthrow of an autocratic regime that was involved in grand-scale corruption and capital flight. The uncertain environment has stifled investment and slowed growth.

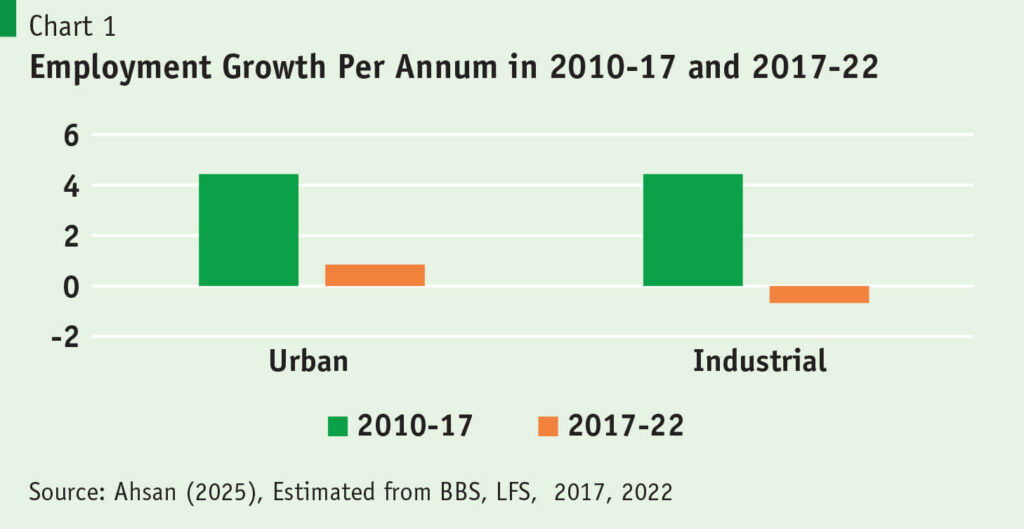

Moreover, these short-term economic instabilities have their roots in the lack of structural development and reforms in Bangladesh. Economic diversification has been limited, trade with the world as a share of GDP – a key indicator of competitiveness – has declined markedly and lags far behind neighboring competitor countries; both revenue collection and public investment in social sectors and infrastructure are woefully inadequate. Human capital development and, specifically, the quality of education and even health improvements are now stalling. The impact of these failures has been widespread – economic growth in FY 2025 at 3.7% has been the lowest since 1991, except in the Covid-affected FY 2020. However, more ominous and structurally challenging is the sharp drop in employment growth in 2017-22 in general and the absolute decline in industrial employment during the same period.

Effective urbanisation–urbanisation that attracts investment, people and workers; provides higher productivity jobs, and good public services and amenities–lies at the intersection of the challenges. Only well-functioning urban centers can provide ecology and scale for infrastructure, finance, public services, education, workers, and markets for attracting investment, creating higher productivity jobs, diversifying the economy, and accelerating growth. Worth noting, urban development has already been critical in achieving manufacturing and economic growth in Bangladesh. The urban population of Bangladesh has grown about 10 times since independence, the fastest in South Asia, which enabled a structural transformation of the economy and a five-fold increase in real per-capita incomes.

The critical challenge for Bangladesh is to sustain and improve the quality of urban development.

Now, however, the critical challenge for Bangladesh is to sustain and improve the quality of urban development. Bangladesh faces several critical challenges. As much as a third of urban population growth occurred in Dhaka, where the population grew at an annual rate of 5.4% between 1974 and 2017. Other large cities, i.e., Chattogram and Khulna, with populations of more than one million, have grown at a far lower rate of 1.7% p.a. Not only that, but overall urban population growth has also slowed in recent years from over 7.8% p.a. in the first two decades to less than 4% in the last two decades. Further, the sharp slowdown in urban employment growth to 0.4% per year over 2017-2022 compared to 4% in the previous period (2010-17) suggests declining dynamism.

Overall urban population growth has also slowed in recent years from over 7.8% p.a. in the first two decades to less than 4% in the last two decades. Further, the sharp slowdown in urban employment growth to 0.4% per year over 2017-2022 compared to 4% in the previous period (2010-17) suggests declining dynamism.

With a housing deficit estimated to have crossed eight million units in 2021 (Jahan, 2021), urban land prices have sharply increased. The most dramatic has been the nearly 100% annual increase in land prices in Dhaka between 1972 and 2012 (Ahmed, 2017). Given these trends, not surprisingly, more than half of the urban population lives in slums. Bangladesh’s long-term growth prospects will decline without addressing these challenges to the quality of urban life.

The urban development patterns and impact are the topic of this paper. Section B provides some theoretical background and international evidence. Section C presents some stylised facts laying out the urban development challenges for Bangladesh: (a) urban development trends; (b) excessive dominance of the Primate City; (c) some promising developments in terms of churning and centrifugal forces; and (d) some concerning trends about the distribution of urban growth bypassing secondary cities. Section D concludes. In Part II of this paper for publication in the next issue of Policy Insights, we will discuss the adverse implications of these developments and the institutional and policy failures that are driving these results.

B.International Experience and Theory

As noted earlier, the association between urban development and economic growth is one of the most robust relationships in economics. Let us take the urban population of 93 countries (with populations greater than 20 million), their growth from 1992 to 2017, and account for country fixed effects and time trends. We find a robust relationship: a one percentage point increase in the share of the urban population is associated with about a 1.1% increase in PPP dollar per capita incomes after controlling for country effects and time trends. Interestingly, these cross-country results match Bangladesh’s experience well. While urbanisation in Bangladesh rose from 8.8% in 1974 to about 39% now–i.e., nearly four times–real per capita incomes have increased by nearly five times.

While urbanisation in Bangladesh rose from 8.8% in 1974 to about 39% now–i.e., nearly four times–real per capita incomes have increased by nearly five times.

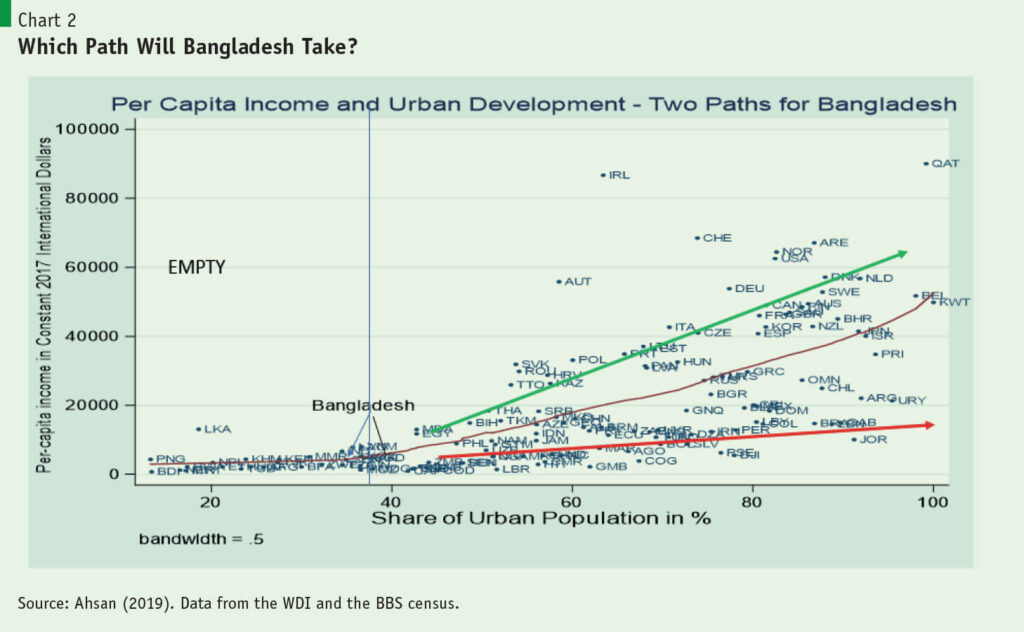

Because, as the chart below makes clear, the relationship between urban development and per capita incomes is non-linear, denoted by the thin red curve drawn using econometrics. Countries above the curves are those that have successfully used Urban Development to generate growth. Countries below that curve are those that have urbanized but were not able to generate growth. There are three implications of this diagram. First, without urban development, there is no growth, as the left-hand corner makes clear. However, second, urban development, per se, does not lead to growth. See the pack of countries on the lower right-hand side corner where the red line goes. Finally, there are countries in the top right-hand corner – those that have urbanized successfully.

Bangladesh, with an urban population of 59 million (BBS estimate is 54 million, while UN DESA estimate is 69 million), roughly stands on the middle non-linear curve. The question for Bangladesh now is which part will it take? Will it move along the green line above the curve, or will it move along the red line below the curve?

The answer will depend on the policies and institutions chosen by Bangladesh for economic growth and urban development. If the right policies and institutions are used, then Bangladesh will follow the green line of higher growth. Otherwise, it will be stuck in the middle-income trap of the red line. What are these good policies and institutions? We will now turn to theory and literature to answer that question.

Two major economic forces link urbanisation to economic growth: returns to scale and agglomeration economies. The first is economies of scale arising from high fixed costs and lumpy infrastructure investments. These become affordable by serving large numbers of people. Agglomeration externalities – that is, the benefits of concentration and clustering of people and economic activity – arise from pooling and creating the availability of labor, intermediate goods, and markets to which products can be sold. A final agglomeration externality is the diffusion of knowledge as farms and people learn from each other by being together. Once a clustering of industry and economic activities starts in cities, agglomeration economies such as returns to scale, externalities, and network effects come into play to create further concentration and increase the size of the market cyclically. Agglomeration effects can be of two kinds: localization economies and urbanisation economies. The first, typically in mid-sized cities, leads to intra-sectoral externalities, increasing firms’ productivity within one sector. The second relates to inter-sectoral externalities that provide productivity spillovers across sectors, leading to the rise of productivity across different sectors and the economic diversity of large cities.

The opportunity to work in higher productivity and higher wage jobs in the urban areas draws migrant populations from rural areas, leading to faster urban growth and urbanisation. In addition, the amenities (housing, public services, recreation) that urban areas can provide better than rural areas, and their preference for such amenities draws people to urban areas, creating urban dynamism.

The central role of externalities in urban development creates two classes of market failures. First, fixed costs and externalities create complementarities in urban growth and the need for coordination. Markets are initially unable to provide the scale, coordination, services, and amenities needed to support urban development adequately. Second, the presence of externalities means there is a wedge between social/public and private returns (Ahluwalia et al., 2014; Ahsan, 2019) because private agents – employers and workers – do not internalize the gains of agglomeration externalities of a growing city or town. As a result, left to themselves, cities initially grow less than optimally. That is where the Government’s provision of public goods and services, such as infrastructure, education, and other social services, becomes necessary to promote urban growth.

On the other side of the coin, as cities grow, the costs of diseconomies of scale and negative externalities – such as the costs of congestion and pollution – start outweighing the benefits of scale and agglomeration. The rising costs of immobile factors of production, such as land, water, or other factors whose inelastic supply raises costs prohibitively. Ultimately, when the costs of these diseconomies and supply problems overcome economies of agglomeration, a city should stop growing.

All these factors work to limit primate city size to the optimum point. Nevertheless, here again, market failure works to push a city’s growth beyond the optimum point. It happens because private agents do not internalize the costs, and network externalities continue to operate as if other firms, workers, and services are already there. Thus, new firms and workers find it advantageous to continue to locate in the larger cities even though overall welfare declines due to congestion and pollution problems and because resources are misallocated to the primate city instead of to other cities. Thus, primate cities continue to grow beyond their optimal levels because these market failures create circular cumulative causation (Henderson et al., 2001). Due to these factors, there is an inherent bias in pure market forces to lead to the overgrowth of cities. Empirical research suggests that many cities are too large in practice, where social marginal costs (congestion, commuting, environmental, and coordination failures) exceed social marginal benefits (Henderson et al. 2001).

All these factors work to limit primate city size to the optimum point. Nevertheless, here again, market failure works to push a city’s growth beyond the optimum point. It happens because private agents do not internalize the costs, and network externalities continue to operate as if other firms, workers, and services are already there.

Political economy also plays a role in creating excessively large and dominant primate cities. The geographical location and concentration of the political elite in a city can bias economic decisions about the location of economic activity. The elite can direct more of both public and private resources to develop the primate city to the neglect of other cities. Added to the forces of market failure that drive excessive concentration, the overgrowth of the primate city can lead to a sub-optimal allocation of resources as well as negative externalities of congestion and a poor environment.

One evidence of this excessive growth of large cities is significantly higher population densities in developing country cities in South and South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa compared to cities in developed economies. Consistent with this trend, the productivity levels of workers in developing country cities are no longer as significant as they were during the urbanisation of developed economies (Henderson and Taylor, 2020). Hence, we have the phenomenon of urbanisation without industrialization and development represented by the red line in Chart 2 above.

The theory of urban development rests on two key points. The presence of agglomeration externalities (including negative externalities) and economies of scale. These, in turn, lead to the separation between private and social returns and costs and coordination challenges – a number of complementary factors have to work together. Inherently, the market and the private sector cannot address these issues and government intervention, and policies are required to develop cities, manage them and prevent overgrowth that leads to social losses. We will discuss these issues in more detail in Part II of this article, which will appear in the next issue of Policy Insights.

C.Stylised Facts About Urban Development in Bangladesh

Four trends stand out in a review of the stylised facts concerning urban development in Bangladesh in recent years. First, the continued predominance of the primate city, Dhaka, and its adverse effects on Bangladesh’s development. Second, the slowdown in urban population growth is much below past projections. Third, welcome evidence of some churning in the distribution of urban population growth. Finally, the more disturbing evidence of the bypassing of the urban population away from secondary cities to smaller towns.

Excessive Predominance of Primate City

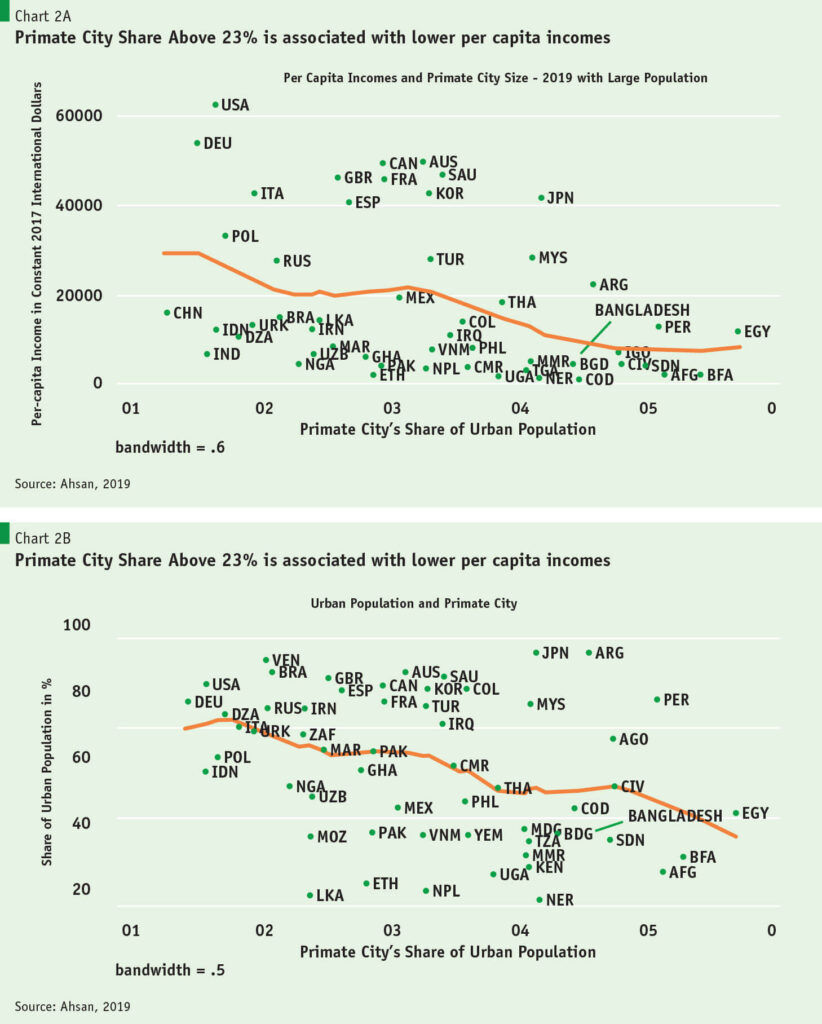

Empirically, the effect of excessive growth of large cities is well brought out in the case of primate cities – that is, the cities with the largest share of urban population in the country. International evidence and research (Ahsan (2019), Henderson (2000)) have suggested that there is an optimum threshold size of the primate city. When the share of the primate city population in total urban population crosses that threshold, approximately 23%, it starts to have an adverse impact on per capita income levels (Chart 2A) through its effects on adversely affecting overall urbanisation rates (Chart 2B, Ahsan, 2019). The mechanism is that due to the market and political economy failures mentioned above, it draws in disproportionately higher public and private resources to the primate city, away from other urban areas. The process is similar to the concept of Krugman’s “Externality Shadow” but extended nationally, where the primate city’s externalities affect overall urban development in Bangladesh (Fujita et al., 1999). It is also similar to the concept of the “parasitic” city (Hoselitz, 1955) as opposed to a “generative” city: i.e., a city that extracts more resources from its surrounding region and the country than the value it produces.

As Charts 2A and 2B make clear, Bangladesh’s primate city share has crossed well beyond the 23% threshold level. Thus, the implication is that the concentration of the population in Dhaka is adversely affecting both urban development and per-capita incomes. We examine the evidence below to test the first implication. Earlier research has suggested that the excessive concentration in Dhaka costs the economy by 6% or more due to internal costs of congestion and pollution in Dhaka (Khan and Islam, 2013), due to lower economic productivity (Henderson, 2000) and by adversely affecting overall urban growth (Ahsan 2019).

Slowdown in Urban Population Growth

Determining the trend in Bangladesh’s urban development is a challenge, given the absence of consistent definitions and time series data since 2011. Nevertheless, the following can be stated about Bangladesh’s population growth. Bangladesh’s urban population has grown between 4.6 and 4.7% p.a. since 1974, the fastest in South Asia. Since 2001, Bangladesh has crossed a milestone as urban population growth has been higher in absolute numbers than rural population growth (Islam 2018), as further confirmed by this paper’s estimates for the past two decades since 2011.

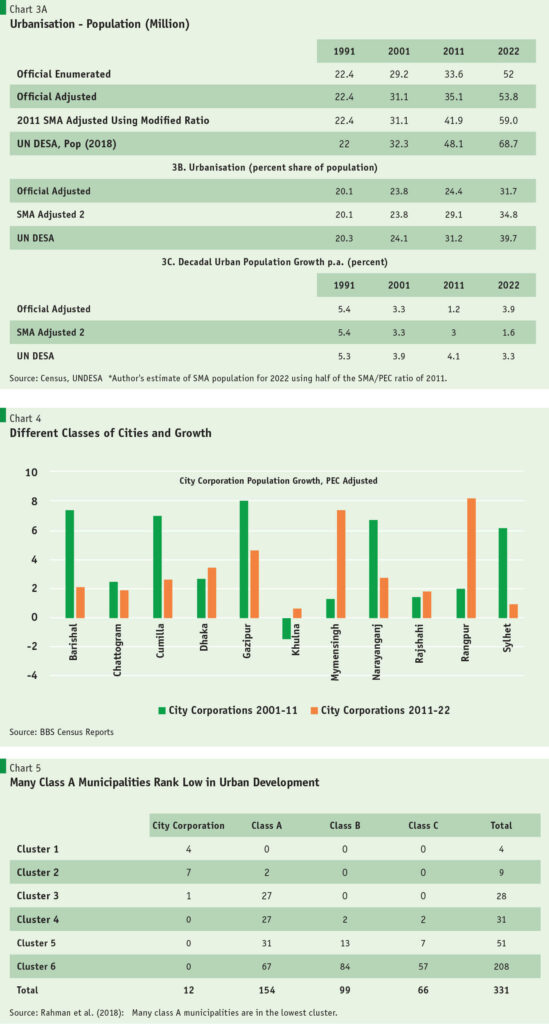

Urban population growth has slowed down after the fast growth of earlier decades, as seen in other countries too. However, in Bangladesh’s case, the slowdown has been marked using official numbers. The official post-enumeration census (PEC) estimate indicates that the urban population in 2022 is nearly 54 million, reflecting a notable deceleration in urban population growth compared to the UN-DESA projection of 69 million (see Chart 3 A). Using the Census 2022 numbers, we arrive at an urban population share for Bangladesh at 31.7%, far below the 39.7% of the UN-DESA projects (Chart 3 B). Also, if we accept the official 2011 and 2022 urban population numbers, we have an odd kink in the growth rate. The growth rate decelerates sharply from 2001 to 2011 to 1.2% and then accelerates to 3.9% over 2011-2022 (Chart 3 C). This latter growth is inconsistent with the significant slowdown in urban employment growth (from 4% over 2010-2017 to 0.8% over 2017-2022) and the unexpected significant rise in the share of agricultural employment reported in the 2022 LFS.

The problem arises because in the 2011 official numbers, the Statistical Metropolitan Area (SMA) adjustment to Dhaka and Chattogram was made, which increased urban population numbers by 19% to nearly 42 million (Chart 3A) in 2022. These adjustments included a number of unions and urban areas outside of but contiguous to the cities. Most analysts agree that these adjustments were valid. However, the BBS has not made SMA adjustments to the 2022 data and has now dropped reporting the 2011 SMA adjusted numbers. As a result, we have a strange kink in growth numbers. In Charts 3A to 3C, we provide our own unofficial SMA estimates of the urban population by using half of the 2011 SMA-PEC adjustment ratio for 2022. The assumption is that the official 2022 estimates have accounted for half of the underestimated figures of 2011. Based on this adjustment, the SMA urban population growth also increased to 3.2% over 2011-2022 from 3% in the earlier decade. This presents a smoother and more reasonable trend that is closer to the UN-DESA estimates. Population growth rates have slowed down, but more gradually.

While BBS urban population numbers are likely to be underestimated, even then, there is a slowdown in urban population growth. Two pieces of evidence support such a proposition. First, there is no controversy that city population growth has slowed down. As the PEC-adjusted numbers for the 11 city corporations for 2011 and 2022 show in Chart 4, population growth slowed down in 8 of the city corporations. Two exceptions – where the population increased – were likely caused by the increase in city land area when Mymensingh and Rangpur became divisional headquarters. In the case of Rangpur, 12 Unions were added to the Rangpur corporation, contributing to the increasing population growth there. Thus, in general, the increase in urban population growth over 2011-22 has taken place mainly outside the major cities. We will return to this point below.

Second, there is good research suggesting that the urban population may be overestimated in some areas. An empirically rich paper classifies 331 towns and cities from the 2011 Census in Bangladesh based on data on five urban spatial features collected from remote sensing: city size (area), urban form (AWMPFD), the ratio of built-up and non-built-up areas, urban growth rate, and total night lights intensity (Rahman et al. 2018). Using these five urban spatial features, the paper classifies the municipalities’ urban development into six groups based on a clustering algorithm. The paper then establishes that urbanisation closely correlates with non-agricultural employment, per-capita income, and expenditures. Nearly 100 of the class A municipalities in the 2011 census, the most developed according to official definitions based on revenue collection, fell in the bottom two of the six clusters of urban development. That is, they are among the least urbanized by this classification (Chart 5 below). We found corroborating evidence to support this finding.

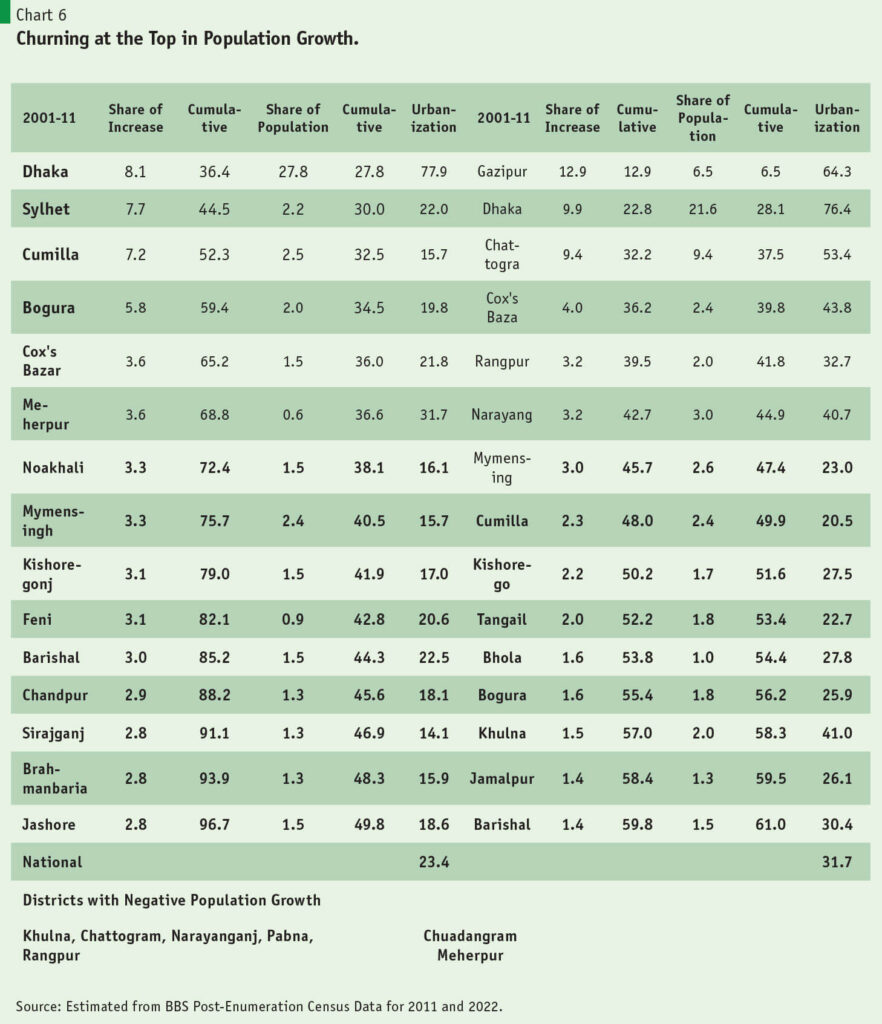

Churning of Urban Population

Although trends in the overall urban growth rate in the last decade are not entirely clear, the evidence suggests that there is churning in the ranks of districts by urban growth. Chart 6 below shows that seven of the top 15 fastest-growing urbanized districts in 2001-11 dropped out of that group in the next decade of 2011-22. These seven were Sylhet, Noakhali, Chandpur, Feni, Sirajganj, Jashore, and Brahmanbaria. They were replaced by Gazipur, Chattogram, Narayanganj, Tangail, Bhola, Khulna, and Jamalpur. Gazipur ranked at the very top by this indicator, accounting for almost 13% of the increase in the urban population.

However, while there has been churning in the ranking of districts by the share of increasing urban population, the urban population has become more concentrated. The top 15 urbanizing cities accounted for 61% of the urban population growth in the 2011-22 period, as opposed to a 50% share in the previous decade.

But what is interesting here is that Dhaka district’s share of the national urban population fell significantly from 28% to 22%. However, the move of the urban population was mainly to the next district of Gazipur, which accounted for the maximum 12% of urban population growth. Chattogram district’s urban population grew by 9.4% after previously declining in the last decade. While Khulna district’s urban population share was modest, 2%, it was also a reversal from the last decade, when it lost its urban population.

Diversion away from Secondary cities.

A more formal approach to examining the distribution of city population sizes and their welfare implication is to use Zipf’s Law, an empirical regularity seen in many phenomena, including linguistics, natural and physical systems and, relevant for us, in the distribution of urban population. In the case of the urban population, the law would be equivalent to

PopCi = Population of Primate City/Rank(Ci).

Where PopCi = population of City i and Rank(Ci) is the rank of the size of city i. This formula states that the second ranking city would have half the population of the Primate City (largest city), the third ranking city would have 1/3rd the population of the primate city and so on.

Before going further, it is worthwhile to explain the logic behind Zipf’s Law in urban population distribution. Zipf’s Law basically upholds the trade-off between the gains of high agglomeration and scale at one end and the costs of congestion at the other end. While it does not have direct welfare implications, it serves as a benchmark to evaluate the distribution of a country’s urban system. A marked deviation from the law would identify the costs of excessive concentration or the costs of inadequate agglomeration.

A rank-order test is used to test Zipf’s Law. We follow the method used in the study of China’s urban system and development by Chen and Lu (2019). Under this “law,” city populations follow the following equation:

Ln(PopCi) = Constant + β * Ln(RankCi) + ei.

Where Ln is the natural log, PopCi i is the population in city i, and RankCi is the rank of urban population in city i.

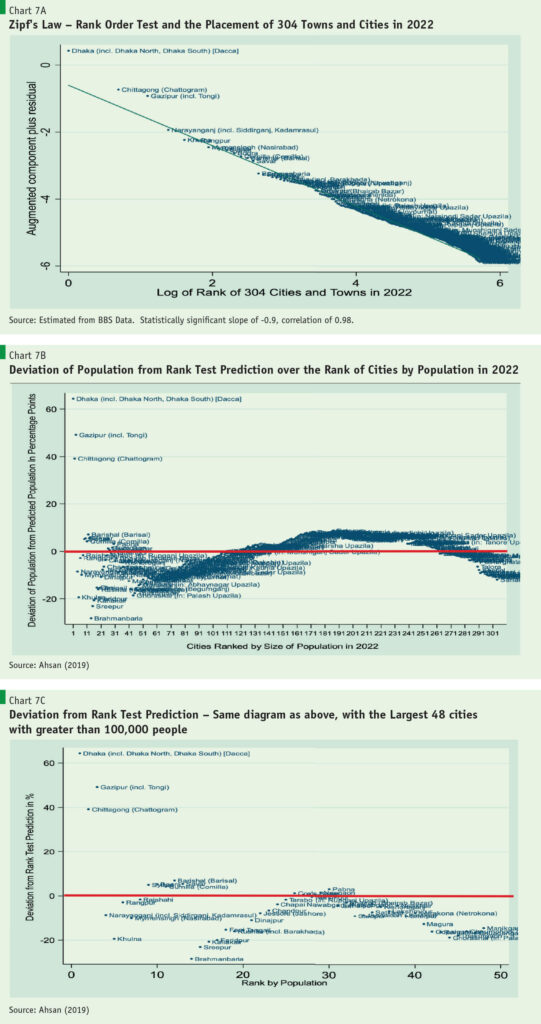

Interestingly, the estimation of this equation in the case of 304 cities and towns of Bangladesh from the 2022 census shows a remarkable consistency of its distribution as predicted by Zipf’s Law, as shown in Chart 6A below, with a regression correlation of 0.98. The β estimate of -0.9 is highly statistically significant. Moreover, it implies that the overall distribution of the urban population displays a sign of weak agglomeration.

However, when we measure deviations of the actual population from the predicted population of the Rank Order test, we have two important findings. The three largest cities have much higher populations than would be predicted by the test. On the other hand, most of the top 100 cities and towns after the most populated cities are underpopulated per the prediction of Zipf’s Law.

A closer look at the 48 largest cities and towns with populations above 100,000 suggests that all but a handful of them are underpopulated compared to the predicted Zipf’s Law Benchmark. In sum, this would suggest that the secondary cities and towns of Bangladesh are suffering from inadequate agglomeration.

D.Conclusion

As noted, this is the first part of a two-part article. In this section, we highlighted the Importance of Bangladesh choosing the right path of urban development. That is the path that aids productivity growth and provides higher productivity jobs to its workers. Otherwise, it will fall into the urban slum trap that many countries face: increasing urbanisation but without the commensurate productivity and job growth. We showed some signs of increasing risks of the latter in the slowdown in urban population growth, especially in the large cities. The data also suggested that while there was some churning in the urban population distribution among the districts, Urban Population growth seemed to be bypassing the secondary cities, leading to the risk of lower agglomeration gains. In the second part of the article, we will discuss some of the adverse implications of these patterns and the policy and institutional failures that are impeding urban development in Bangladesh.

The data also suggested that while there was some churning in the urban population distribution among the districts, Urban Population growth seemed to be bypassing the secondary cities, leading to the risk of lower agglomeration gains.

References:

Ahluwalia, Isher J. Ravi Kanbur, P.K. Mohanty, editors (2014). Urbanisation in India: Challenges, Opportunities and the Way Forward, Sage Publications, New Delhi, California

Ahmed, Sadiq (2017). “Managing the Urban Transition in a Rapidly Growing and Transformational Economy,” The Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Ahsan, A. (2025). “Urbanisation Patterns and Economic Development in Bangladesh – An Overview,” BIDS-PRI mimeo

Ahsan, A. and Wasel Shadat (2025). “Is Urbanisation Promoting Industrialisation in Bangladesh?,” BIDS-PRI mimeo

Ahsan, A. (2019). “Dhaka Centric Growth: At What Cost?” Policy Insights, Policy Research Institute Quarterly, November 2019.

Ahsan, A. (2020). “Bangladesh’s Economic Geography: Some Patterns and Implications,”

Journal of Bangladesh Studies Vol 21 – Issue 1 (2019), Pennsylvania State University, October 2020.

Ahsan, A. and Wasel Sadat (2024). “Is Urbanization Promoting Industrialisation in Bangladesh?” Forthcoming in Urbanisation, Industrialisation, and Development in Bangladesh, BIDS and PRI, Dhaka

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2014), Population and Housing Census-2011, National Volume -3: Urban Area Report

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2017a). Household Income Expenditure Survey 2016/2017

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2017b). Statistical Yearbook 2016

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2013). District Statistics Series 2011

Chen, Zhao and Ming Lu, (2019) “Urban System and Urban Development in the People’s Republic of China” in Wan, Guanghua and Ming Lu, edited (2019). Cities of Dragons and Elephants: Urbanization and Urban Development in China and India, Oxford.

Fujita, M., P. Krugman and A. J. Venables (1999). “On the Evolution of Hierarchical Urban Systems”, European Economic Review, 43, 209-251

Gabaix, X. (1999). Zipf’s Law for Cities: An Explanation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 739–767.

Henderson, J. Vernon and Mathew A. Turner, (2020) “Urbanization in the Developing World: Too Early or Too Slow?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34: 3, 150-173

Henderson, J. Vernon (2003) “The Urbanization Process and Economic Growth: The So-What Question” Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 8, issue 1, 47-71

Henderson, J. Vernon, Z. Shalizi, and Anthony J. Venables (2001) “Geography and Development,” Journal of Economic Geography, I, pp. 81-105

Henderson, J. Vernon (2000) “The Effects of Urban Concentration on Economic Growth”, NBER Working Paper 7503, National Bureau of Economic Research, USA

Hoselitz, B. F. (1955), “Generative and Parasitic Cities,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 3: 278-294.

Islam, Nazrul. (2018). “Urbanisation in Bangladesh: Recent Trends and Challenges,” Daily Sun

Jahan, Sarwar (2021). “Urbanization Challenges, Strategies and Way Forward,” in Agriculture, Land Management, and Urbanization, 8th Five Year Plan, Background Papers, Vol. 3. GED, Planning Commission, GOB

Khan, Tanzila and Mohammad R. Islam (2013) “Estimating Costs of Traffic Congestion in Dhaka City,” International Journal of Engineering Science and Innovative Technology,

Krugman, Paul R. (1991). “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography” Journal of Political Economy, V. 99, p. 483-499

Rahman, Md. Shahinoor, Hossain Mohiuddin, Abdulla-Al Kafyd, Pintu Kumar Sheele,

Liping Dia (2019) “Classification of cities in Bangladesh based on remote sensing derived spatial characteristics” Journal of Urban Management 8 (2019) 206–224.

Kwok Tong Soo, (2005). “Zipf’s Law for cities: a cross-country investigation,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 35, (3), 239-263

World Bank (2015). Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability, Washington, D.C.