Macroeconomic Imbalances: A Tale of Two Episodes

By

It is quite normal that economies pass through certain episodes of macroeconomic imbalances and adjust economic policies or allow the market forces to correct the imbalances. Countries with strong economic growth performance have also gone through episodes of macroeconomic imbalances as happened recently in India. Bangladesh is no exception in this respect. Despite its sustained economic growth at a respectable pace in recent years, it has experienced one episode of macroeconomic imbalances during FY11 and it is experiencing another one at the moment.

Despite many similarities, these episodes of macro instability may have different origins and calls for different policy responses. This policy note analyzes these two episodes in terms of origins/sources of the imbalances during the episodes, the outlook without policy measures for the FY11 episode, and the outcome after policy response for the FY11 episode. While the developments and outcomes of the current (FY18) episode is still unfolding, a systematic policy response still appears to be lacking. Against this backdrop, a discussion on the FY11 episode is worthwhile because of the resolute policy response on the part of the government which brought the imbalances firmly under control.

The FY11 Episode

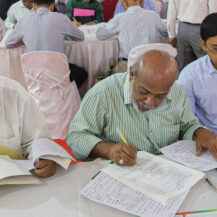

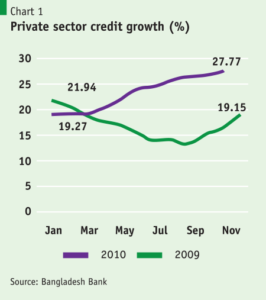

A rapid growth in private sector credit contributing to a huge surge in liquidity expansion was fueled by excessive lending by commercial banks and was also supported by a steady increase in deposit growth (Charts 1 and 2). The emerging problem became visible in March 2011, when the data for credit growth was showing a growth rate exceeding 27.7% by November 2010.

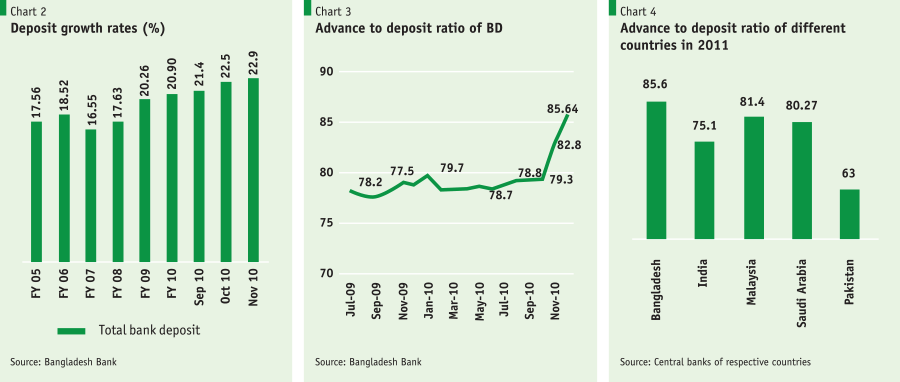

The banks in their push for higher profits pushed the Advance-to-Deposit Ratio (ADR) above 85% in early 2011, well above the norm of less than 80% (Chart 3). Bangladesh was certainly an outlier compared to comparator countries (Chart 4).

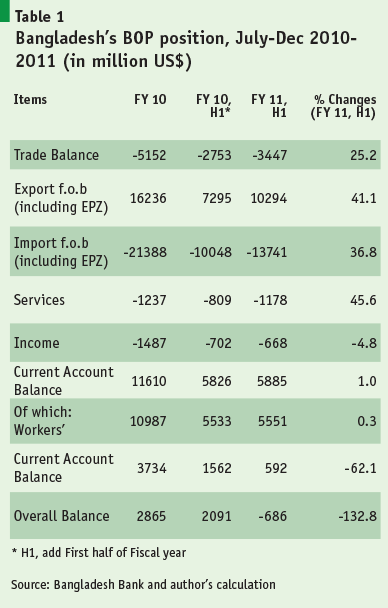

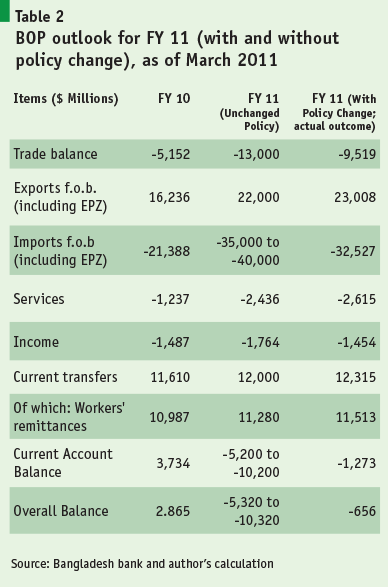

The excess demand pressure arising from the easy monetary policy led to a weakening of the Balance of Payments (BOP) with the overall balance turning negative in the first half of FY11, compared with a surplus of more than $2.2 billion in the corresponding period of the preceding year. While exports rebounded strongly, it was also accompanied by a strong surge in import payments. Because of higher base effect for imports compared with exports and concurrent stagnation in remittance flows, the overall balance recorded a deficit of $686 million in the first half of FY11, compared with a surplus of $2.1 billion in the corresponding period previous year (Table 1).

Question emerged whether Bangladesh had the capacity to finance the emerging BOP gap in early 2011. Based on the prevailing trends, Bangladesh was on the way to a record trade balance deficit of $13 billion and a current account deficit of $5.2 billion in FY11. The projected swing of $8.9 billion in the current account balance and the resulting financing gap of $5.3 billion were matters of deep concern for the authorities. It was ascertained that in the absence of appropriate policy measures, the foreign exchange reserves of Bangladesh Bank could come down to less than $6 billion (2 months of imports) with further downward pressures in the coming months.

The policy options were unpleasant and no single measure could address the growing imbalance on the BOP front. Soon after the identification of the emerging unsustainable imbalances in March 2011, the authorities implemented a number of strong measures along the following lines: (i) eliminated the root cause of the problem—the monetary policy—by abolishing the interest rate cap on lending (set at 13% since 2009) to make the cost of fund higher and determined by market forces; (ii) strong enforcement of the prudential regulation relating to ADR to bring down the average ADR from 85% to less than 80%; (iii) aggressive open market operations to bring broad money (M2) expansion closer to the monetary policy target for FY11; and (iv) liberalization of the exchange rate in the interbank market which led to an immediate depreciation of Bangladesh Taka.

The impact on the interest rate was significant with lending rate going up by 5 percentage points to 18%. The exchange rate adjustment followed the typical Dornbusch style overshooting to Tk. 82 per US dollar from Tk. 69 and thereafter stabilizing at about Tk. 78. The outcomes of these strong policy measures were quick and positive (Table 2).

Did the policies of Bangladesh Bank work? A review of the BOP outcome indicates that import growth slowed down markedly to about $32 billion instead of the earlier trend of reaching $35-40 billion for FY11. The slowdown in LC opening was remarkable: coming down from a peak of more than 60% in January to a moderate pace of 11% in April. A Similar trend was visible in the growth of LCs settled. The external current account deficit was limited to less than one billion compared with more than $5-10 billion projected under unchanged policies.

The Ongoing Episode

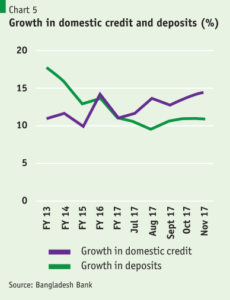

Currently Bangladesh economy is at another crossroad due to the emergence of serious imbalances in both the money market and the balance of payments. The external trade account deficit widened to more than $7.5 billion in first five months (July-November 2017) of FY18, contributing to a current account deficit of $ 4.4 billion over the same period, compared with less than $0.7 billion recorded in the same period a year earlier. Exacerbating the situation, a wide gap is also emerging in credit and the deposit growth rates in the banking system, contributing to an acute liquidity crisis in the banking system. Some banks are also trying to maximize profit by violating macro-prudential conditions like the ADR, as happened during the FY11 episode.

In this episode there is no excess liquidity in the money market, rather there is liquidity crunch in the money market. At the outset, we need to understand why did the liquidity crunch emerge? The ingredients for the liquidity problem was in the making for the last several years as the banking system was experiencing a declining growth in deposits, primarily due to the diversion of financial savings to National Savings Directorate (NSD) instruments/bonds offering interest rates well-above market rates. Since the growth in bank deposits continued to plunge and eventually declined to only 10.6% in December 2017, compared with historical average growth of 16%-18%, and growth in private sector lending accelerated to 18%-19% range, the tightening of the liquidity situation accentuated. Certainly, banks cannot meet 19% credit demand with 10.6% deposit growth. The liquidity problem was also accentuated by the increasing burden of non-performing loans, which limited banks’ role as the source of “Revolving Loanable Fund” and significantly reduced banks’ capacity to expand new credit.

In order to sustain profit growth in an environment of slower deposit growth, many banks started to violate macro-prudential conditions like the ADR. These violations have pushed the ADRs of many banks to 90%-92% range, well above the prudential requirement of less than 85%. Due to this excess lending, some banks are on the verge of becoming illiquid and scrambling for deposits thereby pushing up the deposit rates. Deposit rates of banks have already increased by 4-5 percentage points (more than 75% above the levels prevailing only a few months back). The outcome of this process is already visible in the permanent loss of “single-digit lending rate” that Bangladeshi entrepreneurs and other borrowers used to enjoy in recent months.

Could Bangladesh Bank have prevented this situation on its own? Since the policy with regard to NSD interest rate structure is dictated by the government and in recent times against the advice and plea by Bangladesh Bank, we should not blame the central Bank for pursuing the suicidal NSD policy that was never under its jurisdiction. Bangladesh Bank is trying to minimize the damage by focusing rightly on the macroprudential condition with respect to ADR and has instructed all commercial banks to reduce their ADR ratios to 83.5% and to 89% for Islamic banks. It has also given 11-month time—which is too generous–to the banks for improving their liquidity by lowering their ADRs as appropriate.

Questions may arise whether Bangladesh Bank can and should prevent the rise in the interest rate structure. The interest rates offered for the NSD instruments are currently serving as the anchor for the deposit rates in the banking system and, as long as the NSD rates remain well above the deposit rates in the banking system, the deposit growth will remain subdued and there will be pressure to mobilize deposits and the deposit rates would continue to rise. As a matter of fact, much of this adjustment has already happened with deposit/FDR rates increasing by 4—5 percentage points in most recent weeks. Historical data indicate that, once bank deposit/FDR rates come up to within 1 to 1.5 percentage points of the NSD rates of corresponding maturities, the deposit rates will stabilize and deposits will start flowing back to the banking system.

Since the policy with regard to NSD interest rate structure is dictated by the government and in recent times against the advice and plea by Bangladesh Bank, we should not blame the central Bank for pursuing the suicidal NSD policy that was never under its jurisdiction.

The adjustments brought about by market forces will surely help accelerate deposit growth from its recent historic lows, and at the same time help decelerate credit growth due to the combined pressures of lower ADR and higher interest rates. This convergence of the lending and deposit growth rates will be critical for easing the liquidity crisis in the banking system, allowing it to happen through market forces has inflicted a substantial cost to the economy. This development is essentially the punishment enforced by market forces—an outcome that is undesirable, unfortunate and could have been avoided had the government brought down the NSD interest rate structure when the market interest rate structure was at its lowest points.

It is well established in economic theory that there cannot be two prices or rates of return for the same/similar financial instruments in a unified financial system. Since administered NSD interest rates were not allowed to come down (a very costly decision on the part of the government) to the levels of market determined rates, the market rates had to move up towards the NSD rates to ensure market equilibrium (which is an unfortunate suboptimal and costly outcome).

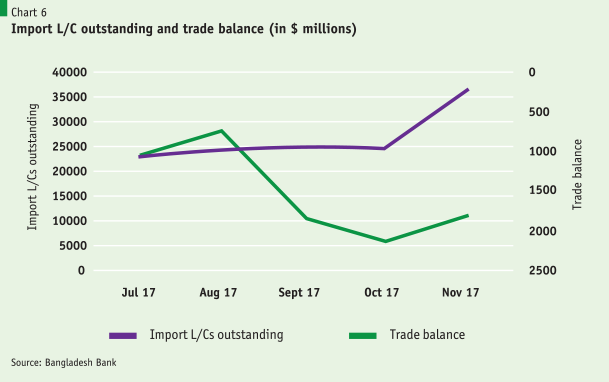

The second major problem is the growing tensions in the interbank foreign exchange market in the face of a mounting balance of payments imbalance. The external current account deficit has surged to $ 4.76 billion in the first half of FY18, compared with a deficit of $ 0.54 billion in the corresponding period previous year. The corresponding trade account deficit was $ 8.6 billion, almost double the level of deficit in the corresponding period last fiscal year. This situation is creating imbalances in the foreign exchange market, forcing Bangladesh Bank to sale foreign exchange in the interbank market to stabilize the exchange rate of Taka against the Dollar. Bangladesh Bank has already injected Dollar liquidity by selling about $ 1.5 billion in the interbank market, but there is no end in sight.

In this respect, Bangladesh Bank should stop injecting dollars into the interbank market to prevent further taka depreciation against the dollar because such interventions would lead to further withdrawal of liquidity from the banking system. Moreover, such interventions should not be used and cannot be successful in changing the market dynamics when the fundamentals indicate continued large imbalances in the BOP and in the interbank foreign exchange market. The interbank exchange rate has depreciated to almost Tk. 83 per dollar, and this is happening despite Bangladesh Bank’s use of moral situations and arm twisting of the banks while at the same time pumping of foreign exchange in the interbank market which is draining down its own reserves.

Bangladesh Bank should stop injecting dollars into the interbank market to prevent further taka depreciation against the dollar because such interventions would lead to further withdrawal of liquidity from the banking system.

This cannot continue for an indefinite period. The country cannot afford to run down its reserves significantly without addressing the fundamental factors contributing to the growing imbalances. No country can sustain a situation such as this forever and Bangladesh will not be an exception. The fundamental problems need to be addressed immediately. The pipeline for import is very strong. The value of new import L/Cs opened during July 2017 – November 2017 stood at $20.6 billion, and the outstanding stock of import L/Cs opened as of end-November was at $ 36.4 billion. As this large stock of L/Cs gets settled, there will be further pressures on foreign reserves of Bangladesh Bank. Unless these imports are backed by foreign financing associated with mega projects, there will be a large drop in foreign exchange reserves which may not be good for Bangladesh economy.

It is therefore important that the government contains the domestic demand pressure by pruning the self-funded large projects that do not have counterpart foreign financing. Some form of belt tightening may be essential over the next 6 months to one year. Higher interest rates and a further depreciation of the currency to discourage imports and encourage exports are important elements to address the imbalances. Tightening the belt in an election year when political economy calls for stimulating economic activity will certainly not be an easily agreeable step politically.

Similarities and dissimilarities of the two episodes

The two episodes described and analyzed above have common elements as well as dissimilarities. Initial conditions are also different in certain aspects, particularly with respect to movement of interest rates. Money market conditions are vastly different. The pressures in the BOP in FY18 is not the result of loose monetary policy as it was the case in the FY11 episode. The BOP pressure observed today is the result of higher domestic demand resulting from accelerated implementation of power and other large infrastructure projects. The slower growth in exports and remittance inflows also accentuated the BOP pressure. Unlike FY11 when interest rates were capped, interest rates are currently market determined and already responded to the liquidity condition by moving upward, potentially helping contain private sector demand pressure. The higher interest rate will also help towards restoring exchange market stability by enhancing the attractiveness of Taka denominated assets.

As regards exchange rate management, the initial conditions were very similar in both episodes, but the policy responses appear to be different. Bangladesh Bank has always been trying to maintain the virtual peg against the US dollar until such time when pressures build up in the exchange market. In FY11, once the pressure built up strongly, the exchange rate was allowed to move freely, and as a result the exchange rate depreciation overshoot before stabilizing at an equilibrium level of about Tk. 78 per $1. At that time, Bangladesh Bank’s reserve cushion was not that high (at $11 billion) and allowing for a significant drawdown by several billion dollars was not a viable option. In contrast, during the current episode, the exchange rate adjustment has been managed in the form of small steps and the extent of depreciation has been limited to about 4%. This time Bangladesh Bank has better reserve cushion and is willing to intervene in the exchange market to ensure stability in the exchange rate. This policy has its costs in terms of reserve loss, but Bangladesh Bank appears to take some hits within a reasonable limit.

The tightening of monetary policy stance is already underway through market forces as the interest rates are increasing rapidly. This higher interest rates although costly for the economy in many ways will, however, enhance the attractiveness for holding taka assets, contain domestic demand and thereby also help stabilize the exchange rate over time. Some degree of depreciation of Taka is unavoidable—a part of the required adjustment has already happened and more will probably be needed. It is important that the process is managed through close monitoring and appropriate policy adjustments (as needed) to avoid being overwhelmed by the brutal force of the market which will be disorderly and much costlier for the economy.