Revisiting the balance of payments and liquidity crisis

By

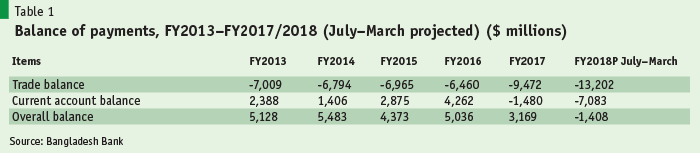

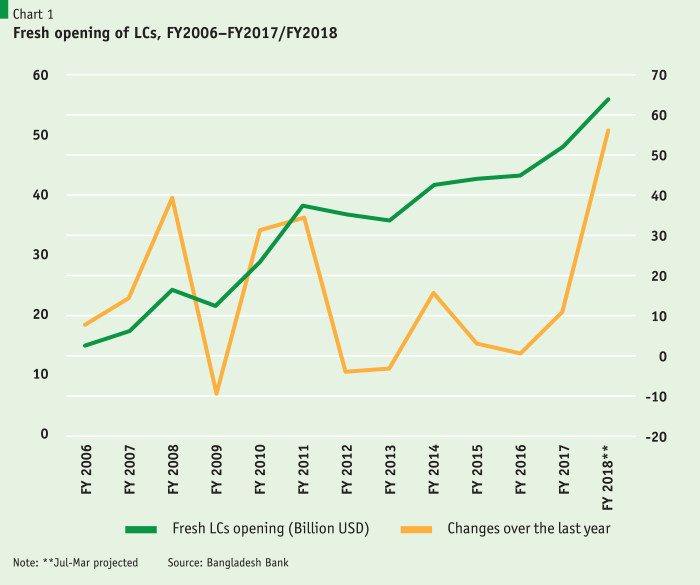

Bangladesh’s ongoing external balance of payments (BOP) and the liquidity problem of the domestic banking system are dominating the discourse on economic developments and policy response. Following a long period of surpluses in the external current account and the overall balance of the BOP, since FY2017 the external accounts have weakened significantly, causing a loss of reserves and a slow but steady depreciation of the Bangladesh taka. In the first nine months of the current fiscal year (FY2018), the external current account deficit reached a record high level of more than $7 billion. At this pace, the current account deficit is likely to reach or even exceed $10 billion in FY2018. This level of current account deficit has never been seen in the history of Bangladesh and is likely to pose challenges in managing exchange rate stability in the coming months. The imbalance in the external current account and pressures on foreign exchange reserves are likely to be accentuated in the coming months, since outstanding letters of credit (LCs) opened but not settled are still showing 55% plus growth over the corresponding period last year.

The liquidity situation of the commercial banks appears to have improved, at least temporarily, as a result of the easing of macro-prudential conditions related to the Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR) and the increase in the limit on the government deposits to be held with private commercial banks. While the two measures have brought some relief to some banks – which is temporary and also reversible – it would be interesting to observe whether we will experience any sustainable improvement in the liquidity situation of the banks.

This article assesses the appropriateness of the measures taken by Bangladesh Bank in response to the two problems. It analyses developments in the BOP and the money market following or in response to the measures adopted by Bangladesh Bank and suggests in passing some remedial measures that are appropriate in the current context.

Imbalances on the external front

Imbalances on the external BOP front are increasing steadily. The external current account deficit, which traditionally used to be in sizeable surplus, turned negative in FY2017 and has further deteriorated throughout FY2018. As of end-March 2018, the current account deficit stood at $7.1 billion, which is much higher than the deficit level of $4.3 billion projected for the full year in Bangladesh Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement of January 2018. By the end of this fiscal year, the current account deficit is likely to reach $10 billion, equivalent to almost 3.75% of gross domestic product (GDP) – a level that is not sustainable over the medium and long term.

A sharp increase in import payments (26% growth during the July–March period) against slow export growth of about 6% has contributed to a record deficit in the trade balance. Based on current trends, the trade account deficit is likely to reach $18 billion, almost double the level of last year and almost three times the deficit level of FY2016. As the external current account deficit approaches $10 billion, there may be a permanent shift in Bangladesh’s BOP structure – we have moved to a new normal. This new normal will continue to be characterized by a sizeable current account deficit. The years of sustained surplus positions in the current account are probably gone for the foreseeable future, if not permanently.

The years of sustained surplus positions in the current account are probably gone for the foreseeable future, if not permanently.

This significant shift in the structure of the BOP in itself is not a problem as long as it is funded from capital and finance account inflows. Since the surge in imports owes at least partly to large import payments associated with implementation of foreign debt-financed mega-projects, the payment obligations are to a large extent funded by accumulation of foreign debt. However, concerns are deepening about Bangladesh Bank’s capacity to maintain exchange rate stability, when outstanding LCs opened but not settled stood at $56 billion as of March 2018, an increase of 56.9% over the corresponding month last year. A surge in LC opening of this magnitude has never been seen in the history of Bangladesh. Except on two occasions, in FY2008 and FY2010/FY2011, when growth in outstanding LCs surged by 40% and 34%, respectively, growth rates in LC opening have usually ranged between -10% and +20%, generally growing in line with the actual level of imports. The 40% surge in LCs opened in FY2008 was associated with an increase in imports in the aftermath of cyclones Sidr and Aila and two rounds of major floods that caused widespread damage to homes, crops and infrastructure. The surge FY2010/FY2011 was the result of overheating of the economy owing to lax monetary policy. In FY2008, since imports associated with relief and rehabilitation were funded to a large extent from external sources, there was no pressure on the exchange rate and the loss of reserves was manageable. During the FY2010/FY2011 episode, the reserve loss was contained by allowing the exchange rate to depreciate by about 14% in one go.

Based on the discussion of past developments, it would be interesting to observe how the exchange rate depreciation pressure is being managed currently and whether this is the right approach. In view of elections and other considerations, Bangladesh Bank is trying to maintain exchange rate stability through a combination of direct sale of foreign exchange on the interbank market and putting pressures on authorised foreign exchange dealers to keep buying and selling rates stable. However, despite the sale of almost $2 billion on the interbank market by Bangladesh Bank, authorised foreign exchange dealers are facing a serious imbalance between supply and demand of foreign exchange. Many authorised dealers are misreporting the true the exchange rate to Bangladesh Bank by understating the extent of taka depreciation and charging the additional costs to other operational expenses. Given the outstanding level of opened LCs, the pressure is likely to increase further in the coming months. This is despite the fact that a large part of the LCs are related to ongoing mega-projects that are being debt-financed from external bilateral and multilateral sources.

The way the exchange rate is being managed has a number of problems:

- Compared with one-step significant devaluation of the taka, the current approach does not address the root cause of the problem with full force and thus imbalances persist.

- Since a major correction in the exchange rate of the taka is perceived to be overdue, the exchange market remains unsettled and many exporters are delaying repatriation of export proceeds and under-invoice exports, contributing to slower growth in exports.

- Importers are rushing to banks to open LCs and lock the exchange rate with a view to avoiding the costs associated with a significant depreciation in the near future.

- Foreign investors tend to cash out of their portfolio investments in Bangladesh and wait on the sidelines to come back to the market after a major step devaluation, which is also depressing the stock price index.

- Bangladesh Bank has failed to build up reserves and is slowly drawing down its reserves, implying a sharp decline in its import coverage, which still remains respectable at about six months of the current pace of annual imports.

The essential question is: should Bangladesh Bank prolong the pain of BOP adjustment over a long period and perhaps until after the election? Or should it bite the bullet now and go for a major one-step devaluation of the currency to restore BOP equilibrium? Certainly, the first approach, which is the current one, is costly for the economy and for Bangladesh Bank, and also entails higher risk of an uncontrolled exchange market in the months just before the national elections. The decision lies with Bangladesh Bank, and only time will tell whether it will really succeed in its efforts to contain the pace of the exchange rate depreciation until the end of the year, and at what cost to the economy.

Liquidity problem of the domestic commercial banks

Two major and one minor factor have contributed to the current liquidity crisis in the banking system and the consequent upward surge in the interest rate structure.

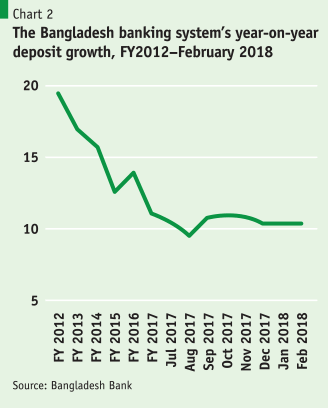

The first is a sharp decline in the growth of deposits in the banking system, from 19.4% in FY2012 to the lowest point of 9.5% in September 2017, thereafter remaining at around 10%. Certainly, a deposit growth rate of 10% cannot sustain private sector growth rates of 16–18%, which are needed for the economy to grow at more than 7% per annum.

The second factor is the high amount of non-performing loans in the banking system, which severely restricts the amount of new loanable funds and undermines the revolving nature of banks’ pool of such funds. Although, according to Bangladesh Bank statistics, the amount of non-performing loans represents more than 10% of the assets of the banking system, it is widely believed that the actual amount is more than twice the published figure.

The third, relatively minor but still important, factor is the sale of US dollars by Bangladesh Bank on the interbank foreign exchange market. For every US dollar Bangladesh Bank sells, it also withdraws liquidity from the banking system of about Tk. 83. Selling $2 billion on the interbank market has led to at least Tk. 166 billion-worth of liquidity being withdrawn from the banking system.

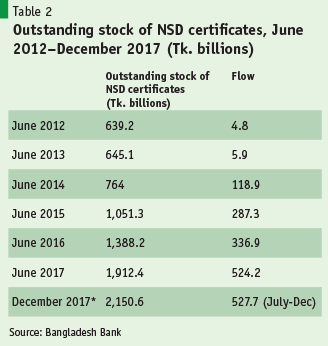

The sharp decline in deposit growth in the banking system is attributable to two major factors: 1) diversion of funds to National Savings Directorate (NSD) deposit instruments lured by markedly higher interest rates; and 2) drying-up of the injection of liquidity through the BOP accounts, represented as increases in net foreign assets (NFA) of the banking system, owing to the current imbalance in the BOP.

The sharp decline in deposit growth in the banking system is attributable to two major factors: 1) diversion of funds to National Savings Directorate (NSD) deposit instruments lured by markedly higher interest rates; and 2) drying-up of the injection of liquidity through the BOP accounts, represented as increases in net foreign assets (NFA) of the banking system, owing to the current imbalance in the BOP. The NSD instruments attracted only about Tk. 5–6 billion during FY2012/FY2013, when the spread between the NSD and bank interest rates was modest. However, as the spread in interest rates has widened since FY2014, more and more household and institutional savings have been diverted to NSD instruments. The cumulative amount of funds going to NSD instruments is estimated to be almost Tk. 1.8 trillion during FY2014–December 2018. By the end of F20Y18, the amount could increase by Tk. 200 billion, taking the cumulative amount over the past five years to Tk. 2 trillion. This massive diversion of funds has contributed significantly to the massive slowdown in deposit growth in the banking system.

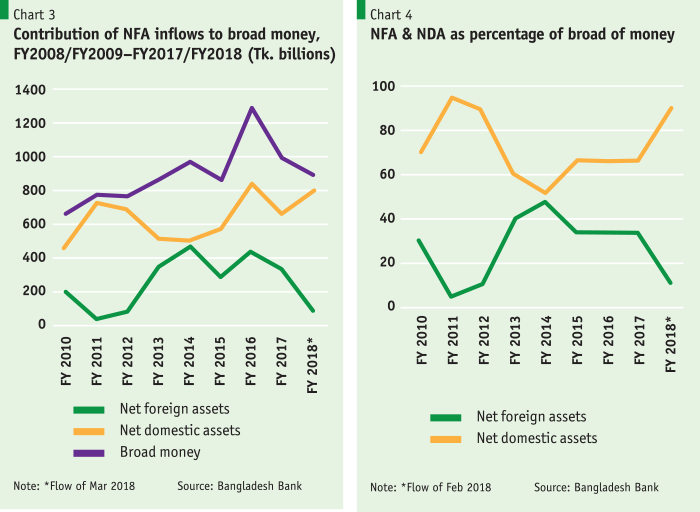

While the decline in deposit growth has broadly followed the pattern of diversion of funds to NSD instruments, we might raise a question as to why the banking system’s deposit growth and liquidity position deteriorated so fast in early FY2018. The answer to this lies in the fact that money supply in Bangladesh was being driven significantly by the inflow of net foreign assets deposited in the banking system through surplus positions in the BOP. As the BOP position deteriorated, the injection of liquidity and deposit growth through NFA tapered off, turning negative in recent months. During the period FY2013 through FY2017, cumulative inflows through NFA amounted to almost Tk. 1.9 trillion. It is no surprise that, when such a major source of liquidity in the money market dries up as a result BOP difficulties, this leads to an overall shortage of liquidity in the money market and, in particular, in the availability of foreign currency.

It is quite normal, when NFA inflows go down, for the net domestic assets (NDA) of the banking system to go up. At the same time, when NDA account for most of the expansion in money supply, the economy tends to face scarcity of foreign exchange. This happened during FY2011/FY2012, when on average more than 90% of broad money expansion was on account of NDA and the money market experienced a serious shortage of foreign exchange and the exchange rate depreciated. As the share of NFA in broad money expansion increased to 30% during FY2013–FY2017, the market was well supplied with foreign currency and there was no pressure on the exchange rate. The exchange rate of the taka against the US dollar remained stable throughout this period. Importantly, in FY2018 monetary expansion has been primarily on account of NDA, which is accounting for more than 90% of broad money expansion. Thus, it is no surprise that there is a crunch in the foreign exchange market.

The government and Bangladesh Bank announced a number of measures in April 2018 to alleviate the liquidity problem faced by the banks. These measures included 1) a reduction of the CRR by 1 percentage point to 5.5% of assets; 2) postponement of the reduction of the lending to deposit ratio (LDR) of banks by 1.5 percentage points to 83.5% till end-March 2019; and 3) allowing government ministries and agencies to increase their deposits with private commercial banks up to 50% of their total deposits. The reduction of the CRR made available for the commercial banks an amount up to Tk. 12,000 crores (0.9% of banking system assets), which is easing the liquidity situation for certain banks that have put themselves in a corner by violating macro-prudential conditions in their efforts to maximise profits while taking unacceptable levels of risk. Unless households are attracted back to the banking system and the BOP conditions ease, leading to a resumption of inflows of NFA into the banking system, there will be no sustainable improvement in the situation. Meanwhile, depositors are exposed to undue risks as a result of the shaving of the CRR ratio.

The decision on increasing government deposits with private banks will have a redistributive impact but no overall impact on the level of deposits held by the banking system. This policy, without any investment guideline, may put government deposits at risk, as happened in the case of the illiquid Farmers’ Bank. The reduction in the LDR should have some tightening effect on the monetary situation, which could help contain import demand pressure and support external sector adjustment. Overall, the measures announced by the authorities are short term in nature, and do not provide a sustainable solution to problems faced by the banking system. And if anything, they further enhance the risks to the banking system and to depositors. These kinds of measures are sending the wrong signals to market participants and also raising moral hazard issues by bailing out errant financial institutions.

The decision on increasing government deposits with private banks will have a redistributive impact but no overall impact on the level of deposits held by the banking system. This policy, without any investment guideline, may put government deposits at risk, as happened in the case of the illiquid Farmers’ Bank.

Concluding observations

Problems remain in Bangladesh with regard to external sector imbalances and tight liquidity in the banking system. Interest rates have already shot up, and there is absolutely no reason for the interest rate structure to come down under the current situation of tight liquidity. If the government is serious about bringing down the interest rate structure, it has to start with a significant reduction in the NSD interest rates. At the same time, an early resolution of the imbalance in the external accounts – primarily through adjustment of the exchange rate – will also be important if we hope to restore normal inflows of liquidity into the banking system through the NFA channel.

As long as these external sector imbalances are allowed to persist, uncertainties will prevail about the impending depreciation of the taka. Because of this lingering uncertainty, exporters will hold on their export earnings by delaying their repatriation, importers will try to rush to book their imports at the prevailing exchange rate, and workers remitting from abroad will continue to hold onto their financial assets. Under these circumstances, inflows of NFA will not resume, pressures on the exchange rate will intensify and the liquidity situation of the banks will not improve.