Is there a trade-off between social protection and investment?

By

Introduction

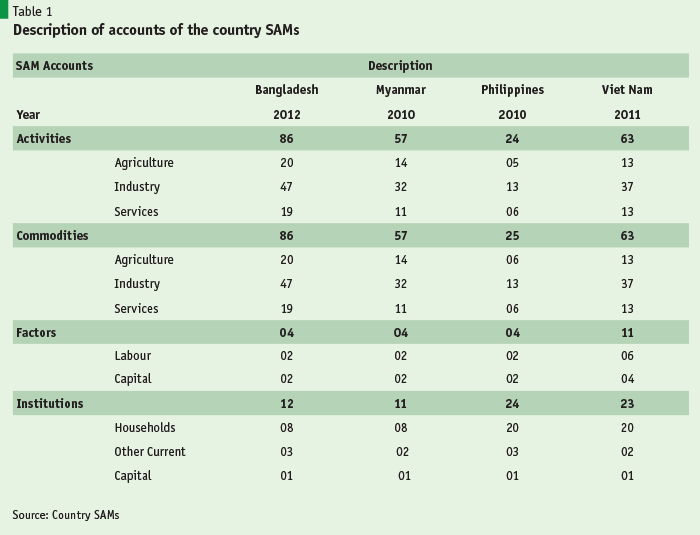

Do social protection schemes generate economic growth? To answer this question – and based on the previous experience in macro-economic simulations – I decided to use a standard economy wide model to estimate the impacts of a universal pension in some selected countries including Bangladesh on economic growth and test it against alternative investment options, in this case investment in construction and capital machinery. The other countries included are the Philippines; Viet Nam and Myanmar. The model used is an economy wide multiplier framework, popularly known as a Social Accounting Matrix (SAM), or the SAM multiplier model.

Data SAM and SAM model

An economy is composed of various agents: producers; factors of production (e.g. labour, capital and land); and institutions (e.g. households, government, enterprises, NGOs, and institutions maintaining linkages with the rest of the world). A data SAM brings together all the numerical outcomes of these agents as accounts for a particular time period –usually a specific year– in a matrix format that preserves the consistencies between supply and demand, income and expenditure, exports and imports, and savings and investment. A data SAM, thus, encompasses all the agents of an economy, capturing their interdependence within a consistent framework. In other words, a data SAM provides a snapshot of the entire economy for a particular time period. The SAM accounts of the four economies are provided below.

A data SAM model has two components: a dependent (endogenous) variable or set of variables; and, an independent (exogenous) variable or set of variables. Changes in independent (exogenous) variables change the values of dependent (endogenous) variables. Accordingly, a data SAM is converted into a SAM multiplier model by separating the SAM accounts into endogenous and exogenous components. Generally, accounts intended to be used as policy instruments – e.g. government expenditure including – such as output, commodity demand, factor return and household income or expenditure– must be made through the interdependent SAM system among the endogenous accounts. For any given injection into the exogenous accounts of the SAM, the influence is transmitted through the interdependent SAM system among the endogenous accounts.

Simulation design and outcomes

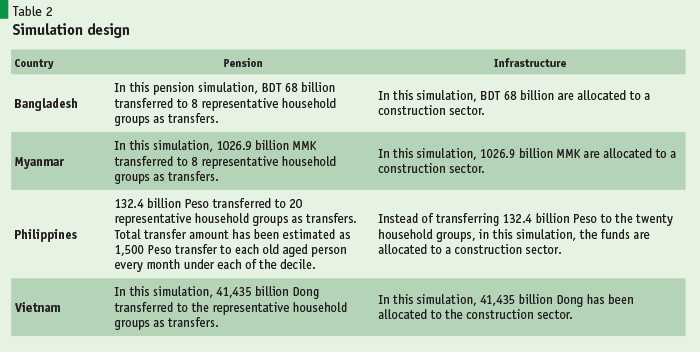

Simulation design: in all cases, two simulations have been considered. The simulations design by the four countries and two types of interventions are shown below.

Simulation outcomes:

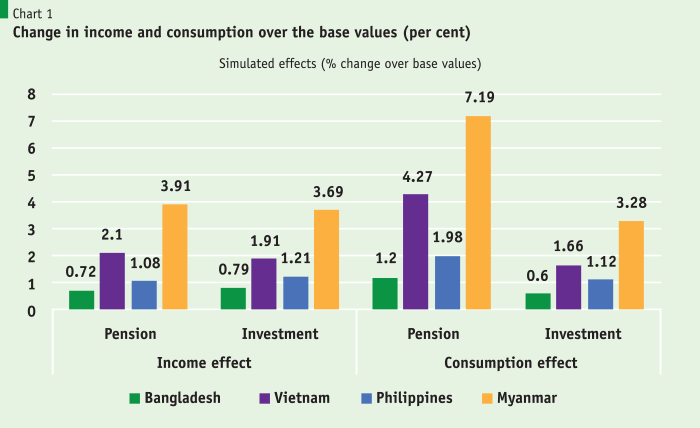

Simulation outcomes have been captured via impacts on the national income (or GDP) and household consumption. They are presented as percent changes over the base values captured in their respective SAMs. In the case of GDP impacts, the results are mixed with impacts on GDP has been found higher for Vietnam and Myanmar under the pension simulations. In the other two cases, the GDP impacts are slightly lower under the pension simulations.

Pension is a direct transfer to household groups compared to an investment scheme which is implemented through enhancing demand for investment generating activities. Thus, the impact of the pension on household consumption expenditure is expected to be substantially higher than that found under the investment scheme. Accordingly, the impacts on consumption are significantly higher under the pension simulation compared to the infrastructure investment simulations.

Thus, the impact of the pension on household consumption expenditure is expected to be substantially higher than that found under the investment scheme.

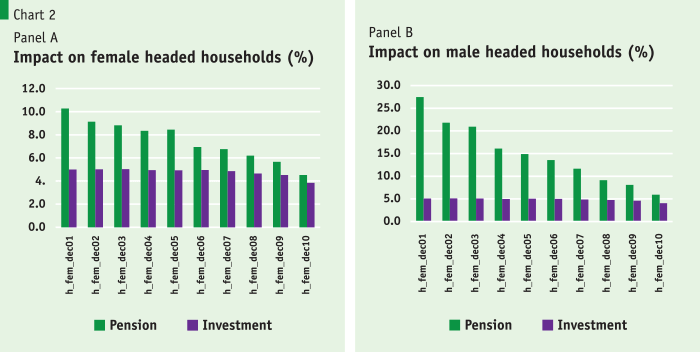

In the case of the Philippines simulation, it was possible to assess income distribution effects of pension and infrastructure investment since households have been categorised by decline. The Philippine simulation provide the more interesting point that the pattern of distribution of additional consumption gain across the representative household groups. Under the pension simulation the distribution appears pro-poor. The simulations provide some very interesting lessons for policy makers.  It would appear that investing in a universal pension (or a social protection scheme) has similar economic impacts to those of investing in infrastructure and capital goods. Moreover, the distribution of economic benefits of a universal pension appears pro-poor. Previously considered to be social welfare on a charitable basis, analysis presented here using macro-simulations confirms that social pension is not a cost to the economy but rather an investment. Furthermore, there is comparative advantage in domestic output from agriculture through increased value added to land and labour through investment in a household-level transfer. Similarly, macro-economic modeling finds comparable advantage in terms of increased as well as pro-poor household consumption. This reinforces the widely acknowledged role of social protection (i.e. pension in this particular case), and in particular cash transfers to beneficiary households, in supporting a consumption-led growth.

It would appear that investing in a universal pension (or a social protection scheme) has similar economic impacts to those of investing in infrastructure and capital goods. Moreover, the distribution of economic benefits of a universal pension appears pro-poor. Previously considered to be social welfare on a charitable basis, analysis presented here using macro-simulations confirms that social pension is not a cost to the economy but rather an investment. Furthermore, there is comparative advantage in domestic output from agriculture through increased value added to land and labour through investment in a household-level transfer. Similarly, macro-economic modeling finds comparable advantage in terms of increased as well as pro-poor household consumption. This reinforces the widely acknowledged role of social protection (i.e. pension in this particular case), and in particular cash transfers to beneficiary households, in supporting a consumption-led growth.

So, governments should not fear that investing in social protection is a wasted resource. Instead, it can generate significant economic impacts and may be as effective an investment as infrastructure…

While these findings are from simulations, it is interesting to note similar findings during the economic recession in the USA, as a result to its fiscal stimulus packages. A study by Zandi (2008) compared the growth impact of a dollar spent on two social protection schemes – the food stamp programme and unemployment insurance – with investment in infrastructure. While the investment in infrastructure had a multiplier effect of 1.6, the spending on the social protection schemes was similar (1.6 for unemployment benefits and 1.7 for food stamps).

While the investment in infrastructure had a multiplier effect of 1.6, the spending on the social protection schemes was similar (1.6 for unemployment benefits and 1.7 for food stamps).

So, governments should not fear that investing in social protection is a wasted resource. Instead, it can generate significant economic impacts and may be as effective an investment as infrastructure and capital goods. In addition, of course, social protection has a significant impact on poverty. The findings suggest that the government of Bangladesh as well as the three countries should seriously consider investing in a universal pension (as well as child benefit) if it wants to generate further economic growth, tackle poverty and, importantly, ensure that the elderly can live out their final years in dignity.

References

HelpAge International (2017), Macroeconomic Impacts of Pension Reforms in Philippines: A SAM Based Simulation Exercise, January, 2017.

HelpAge International (2017), Macroeconomic Impacts of Pension Reforms in Myanmar: A SAM Based Simulation Exercise, July, 2017.

Bazlul Khondker (2015), Is there a trade-off between Social Assistance and Investment in Viet Nam? Application of a SAM based Model, July 2015.

Zandi, M. M. (2008), Assessing the Macro-Economic Impact of Fiscal Stimulus 2008, Report January, 2008. Available at www.moodys.com.