Challenges of the Budget 2023-2024

By

The annual National Budget arguably is the most prominent reflection of the government’s perception of the state of the economy and the main short-to-medium-term economic challenges it is facing. The Budget is then seen as an indication of the way the government seeks to respond to those challenges.

From my perspective, I see the FY2024 Budget facing 4 key challenges: a) Restoring Macroeconomic Stability; b) the Challenge of Revenue Mobilisation; c) Prudent Financing of the Budget Deficit; d) Protecting Social Sector Spending.

A. Restoring Macroeconomic Stability

Few would debate the contention that restoring macroeconomic stability is the foremost and immediate policy challenge facing Bangladesh today. This challenge emerged last fiscal year at around the time when the FY2023 Budget was adopted. The record shows that the FY2023 Budget failed to anticipate the depth of the macroeconomic crisis and ended up without securing any sustained progress with macroeconomic stability.

Inflationary pressures that showed its ugly head since April 2023 spiked at 9.5% in August 2022 and has remained roughly unchanged at 9.24% in May 2023. Blaming this sustained inflationary spike on global inflation and the Ukraine War is politically convenient but not entirely based on facts. While the origins of the domestic inflationary pressures lay in those external sources, they have been sustained for so long owing to the absence of adequate demand management policies.

Evidence shows that countries that adopted demand reduction policies through hikes in interest rates have all succeeded in reducing inflation substantially. For example, inflation decelerated by 65% in Thailand, falling from 7.7% in June 2022 to 2.7% in April 2023. In USA inflation plunged to 4.9% in April 2023, down 46% from its peak of 9.1% in June 2022. In EU, inflation came down to 7% in April 2023, declining by 34% from its peak of 10.6% in October 2022. In India inflation fell by 40% between April 2022 (7.8%) and April 2023 (4.7%). In Vietnam inflation rate spike has been successfully curbed and contained in the 2−3% range.

The pressure on the balance of payments was lowered substantially by reducing imports through higher tariffs and a range of import control measures. But as imports fell and the current account balance improved, the flip side was a substantial slowdown in GDP growth, which is now estimated at 6% for FY2023 as compared with 7.1% in FY2022 and the Budget target of 7.5%. Global experience shows that import controls can at best be a temporary measure and not a sustainable way to manage the balance of payments.

Additionally, these measures could not prevent a substantial worsening of the capital account as foreign direct investment did not expand as projected, short-term trade credit dried up and MLT credit also slowed down. Furthermore, there is evidence of significant capital flight. The signal value of import and exchange controls was highly negative for FDI, suppliers of trade credit, and the confidence of private investors.

So, the FY2023 Budget has ended up with substantially higher rate of inflation than budgeted, a significantly lower GDP growth and continued pressure on the balance of payments.

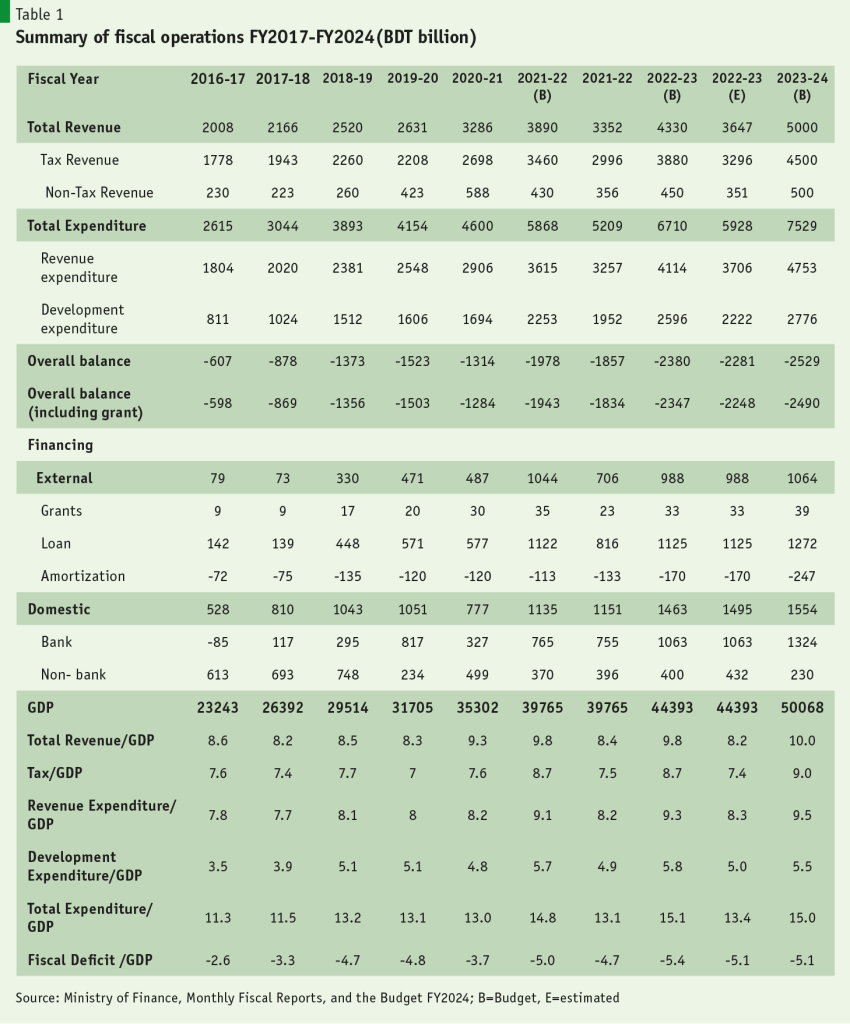

In some ways, the FY2023 Budget contributed to inflationary and balance of payments pressures by running higher fiscal deficits (3.7% in FY2019 rising to 5.1% in FY2023) and resorting to substantial reliance on bank financing of fiscal deficit. Rising fiscal deficit and relying on banking financing of that deficit are inconsistent with inflation control.

The experience with the implementation of the FY2023 Budget provides important inputs for instituting corrective measures in the FY2024 Budget. To what extent this is the case?

The FY2024 proposed Budget targets a GDP growth of 7.5% and inflation rate of 6.0%. It projects a fiscal deficit of 5.1% of GDP and use of 3% of GDP as bank financing. These targets nearly repeat the targets of the FY2023 Budget. So, once again the FY2024 Budget sets an ambitious GDP growth target and there is no effort to reduce demand through lower fiscal deficit or slowdown in the growth of domestic credit by reducing the bank financing of the budget deficit. The inevitable conclusion is that the FY2024 Budget like the FY2023 Budget is focused on boosting growth and not macroeconomic stability.

FY2024 Budget sets an ambitious GDP growth target and there is no effort to reduce demand through lower fiscal deficit or slowdown in the growth of domestic credit by reducing the bank financing of the budget deficit. The inevitable conclusion is that the FY2024 Budget like the FY2023 Budget is focused on boosting growth and not macroeconomic stability.

B. The Challenge of Revenue Mobilisation

The restoration of macroeconomic stability is intimately linked with the challenge of revenue mobilisation. The main source of government revenues is tax revenues. Every year the government sets ambitious tax targets, which it then fails to meet (See Table 1). This situation also emerged during the implementation of the FY2023 Budget. The Budget projected an increase of 30% in tax revenues from BDT 2996 billion actually collected in FY2022 to BDT 3880 billion in FY2023. Based on actual tax collections until March 2023, the estimated tax revenue is expected to reach Taka 3296 billion, which is 15% lower than the target. Because of revenue shortfalls, the tax to GDP ratio has been falling in recent years from its already low levels. The estimated tax revenues in FY2023 amounts to a mere 7.4% of GDP, which is lower than 7.7% of GDP in FY2019.

The inability to introduce meaningful tax reforms over the past several years has constrained tax revenue mobilisation. Ad-hoc tax measures announced during the budget seasons have failed to make a dent in the resource mobilisation effort. This situation will likely repeat itself for the FY2024 Budget. The proposed Budget sets an overly ambitious target of increasing tax revenue to BDT 4500 billion in FY2024 as compared with estimated tax revenues of BDT 3296 billion in FY2023. This amounts to a mammoth increase of 37%, which belies credibility. Actual increase in tax revenue over the past six fiscal years was only 10% per year. The new tax measures proposed in the budget may provide scope for some modest additional increase but the projected 37% increase is absurdly optimistic and the most likely outcome will be a huge shortfall in actual tax revenues.

Meaningful reforms require an overhaul of the tax system that involves major institutional changes in tax planning and tax administration. These reforms include separation of tax planning from tax collection; modernisation of NBR through simplification and digitisation of tax administration; eliminating expenditure accounting requirement in tax filing; removing the interface between tax payer and tax collector; adopting a truly self-assessment system with enforcement though a selective and productive computer based audits; audits conducted by trained and professional tax auditors; converting NBR from a tax policing department to a tax service agency; introducing a proper property tax system; and the full implementation of the 2012 VAT Law.

These are far reaching reforms and can be best introduced through a detailed workout of a modern tax system designed by an Expert Tax Reform Commission (TRC). Similar TRC-based reforms have helped to modernise the Indian tax system and raise the tax/GDP ratio.

There is another potential revenue mobilisation instrument that has not been used to generate revenues. Over the years the government has invested heavily in a range of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Total assets of non-financial SOEs are conservatively estimated at around 20% of GDP. A 10% rate of return on these assets should yield a revenue of 2% of GDP. In reality, SOEs at their peak earned a profit of BDT 152 billion in FY2021, which is a mere 0.4% of GDP. Most SOEs are incurring losses and require subsidies to cover operational deficits. Furthermore, most investments of SOEs are funded through the budget. As a result, net fiscal transfers from the budget, after accounting for profit taxes and dividends from SOEs, is in the range of 2.5–3.1% of GDP over the FY2019–FY2021 periods. Turning around the performance of the SOEs through corporate governance and pricing reforms could yield an additional 1.6% of GDP as revenues for the government.

C. Prudent Financing of the Budget Deficit

In addition to the challenge of keeping the fiscal deficit at below 5% of GDP, the government faces an additional challenge of finding prudent ways of financing the budget deficit. In the current environment of high inflation and pressure on the balance of payments, the government will need to cut the growth of domestic credit. To avoid a crowding out of private sector credit, the government financing of the budget deficit must reduce its use of bank financing. Possible options are to increase reliance on low-cost foreign borrowing and market based domestic borrowing. The high cost of national savings certificates has been a serious problem. While a resolution of this is constrained by political economy issues, a good option would be to fast track the development of a secondary market for T-bills which will allow the Treasury to borrow directly from the public at significantly lower cost than national savings certificates.

D. Protecting Social Sector Spending

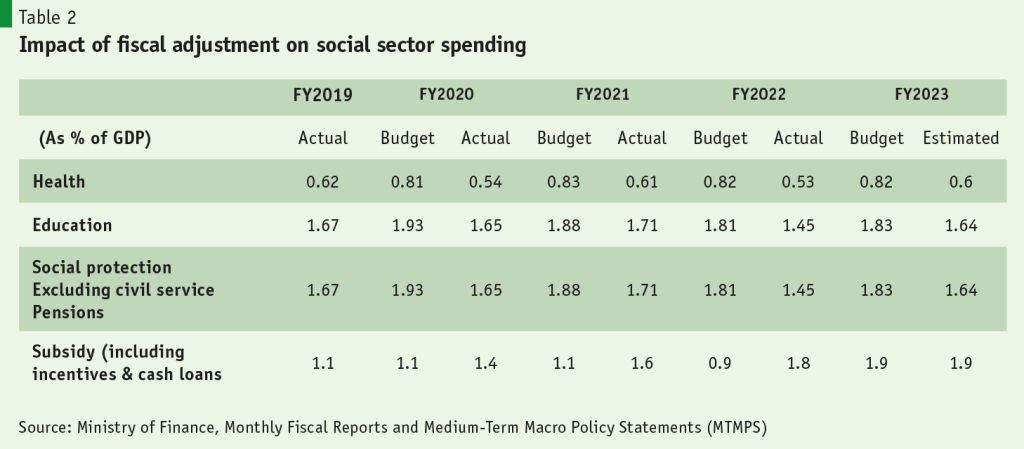

Evidence shows that revenue constraints have hurt the ability to adequately finance spending on health, education, and social protection (Table 2). Since some 50% of the budget is already committed to fixed spending items (wages and salaries, civil service pensions, materials and supplies, security spending, and interest cost) the flexibility for strengthening expenditure priorities in the face of revenue shortfalls is limited.

The tendency to accelerate spending on large, visible and long gestational infrastructure projects may appear politically appealing in an election year but in reality, they do not create immediate benefits for the common citizens unlike income transfers from social protection programs, and spending on irrigation, flood control and water supply where benefits are more direct and immediate.

Even so, the government must make an effort to curb subsidies and phase the implementation of capital-intensive large infrastructure projects, while increasing allocations for health, education, irrigation and flood control, water supply and social protection. Along with efforts to lower inflation these spending can also help the government politically by improving the income levels of the poor and vulnerable. The tendency to accelerate spending on large, visible and long gestational infrastructure projects may appear politically appealing in an election year but in reality, they do not create immediate benefits for the common citizens unlike income transfers from social protection programs, and spending on irrigation, flood control and water supply where benefits are more direct and immediate.