Key Drivers of Bangladesh Success Story Opportunities and Challenges under China+1 Geo-Polynomics

By

In Historical Context

Bangladesh emerged in 1971 as the world’s ninth poorest nation with a poverty rate of over 75%, GDP of USD 7 billion, per capita income of USD 90, infant mortality at 210 per 1000 births, and an average life expectancy of 46 years. Today, Bangladesh is the 35th largest economy in the world by GDP size (25th in PPP USD), GNI per capita of USD 2765 (current USD), and where infant mortality declined to 23 and life expectancy rose up to 72. The country has also gained international recognition as a model for poverty reduction which is down to 19%. Categorised by the United Nations as a Least Developed Country (LDC) since 1975, it has achieved the lower middle-income status in 2015 and today it is the largest graduating (LDC), with graduation scheduled for 2026.

From a ‘Test case of development’, Bangladesh is now being described as a ‘success story of development’. What brought this about and is it sustainable?

The Present Context

Tectonic shifts are now taking place in the world order. No country is an island in this global village. These shifts are consequential for Bangladesh, its economy and its people.

The strong recovery out of the COVID-19 episode has been interrupted by challenges emerging from the Russo-Ukraine conflict. Bangladesh is facing macroeconomic strains – both internal and external – and policymakers are trying hard to grapple with the situation. Elections are closing in so economic decisions are willy-nilly being influenced by political developments. An IMF program is on. But with USD 80 billion of foreign exchange earnings from exports and remittances, supplemented by ODA of about USDS 10 billion and FDI of another USD 4-5 billion, the prospective import bill of about USD 80 billion in the coming year appears manageable and should relieve the stress on the BOP and foreign exchange reserves provided the exchange rate remains flexible, as promised. Containing domestic inflation running at 10% plus is being curbed via monetary contraction and expenditure restraint, following standard prescriptions. Some fundamental reforms in the banking sector and revenue mobilisation have become absolutely critical. We need to wait until after the elections in January to see if the economy resumes its growth trajectory consistent with its potential.

The Long View

To get a good sense of where the Bangladesh economy and society stands, it is necessary to take a long view of the rise of this economy from a ‘basket case’ story to one with a bright future.

Since the decade of reforms in the 1990s, Bangladesh economy experienced rapid GDP growth, averaging 5.7% a year for three decades, lifting the economy from low income to middle income, on the way to graduate out of LDC status in 2026, and on course to reach the upper middle- income country threshold by 2031. Though not extraordinary, it is fair to say that Bangladesh crossed its 50-year milestone (2021) with some sense of fulfilment at the level of progress achieved in human and economic development in the face of heavy odds. The rise of Bangladesh to becoming the world’s No.2 exporter of readymade garments (RMG), propelled by first generation entrepreneurs, is a story of remarkable economic success. RMG prospects look even better under the new geo-economics of China+1.

Though not extraordinary, it is fair to say that Bangladesh crossed its 50-year milestone (2021) with some sense of fulfilment at the level of progress achieved in human and economic development in the face of heavy odds.

In the current development discourse, the name of Bangladesh pops up almost without fail – in the academic debates of leading universities as well as in the corridors of multilateral aid agencies. For underdeveloped nations on the path of development, Bangladesh offers an appealing case study.

Bangladesh is now described by some leading development economists as a success story of development having long shed the derisive epithet of a ‘basket case’. Some economic analysts would describe the Bangladesh phenomenon as the ‘Bangladesh surprise’, while governance experts prefer to think of it as a ‘Bangladesh paradox’ – significant progress despite pervasive governance deficiencies.

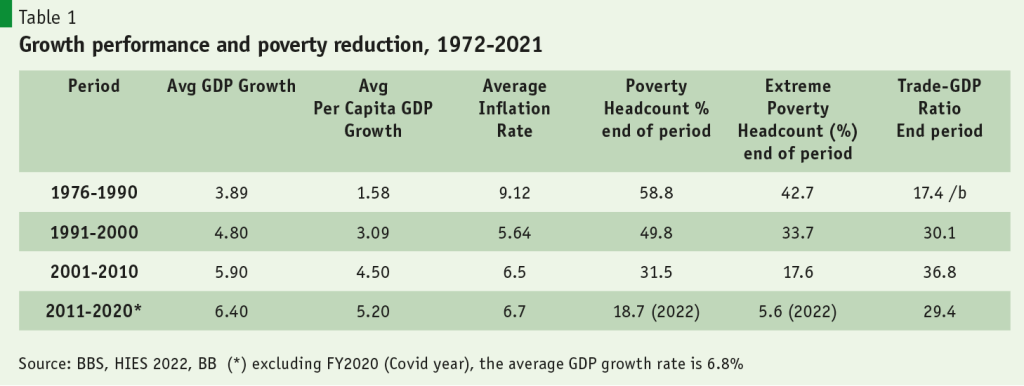

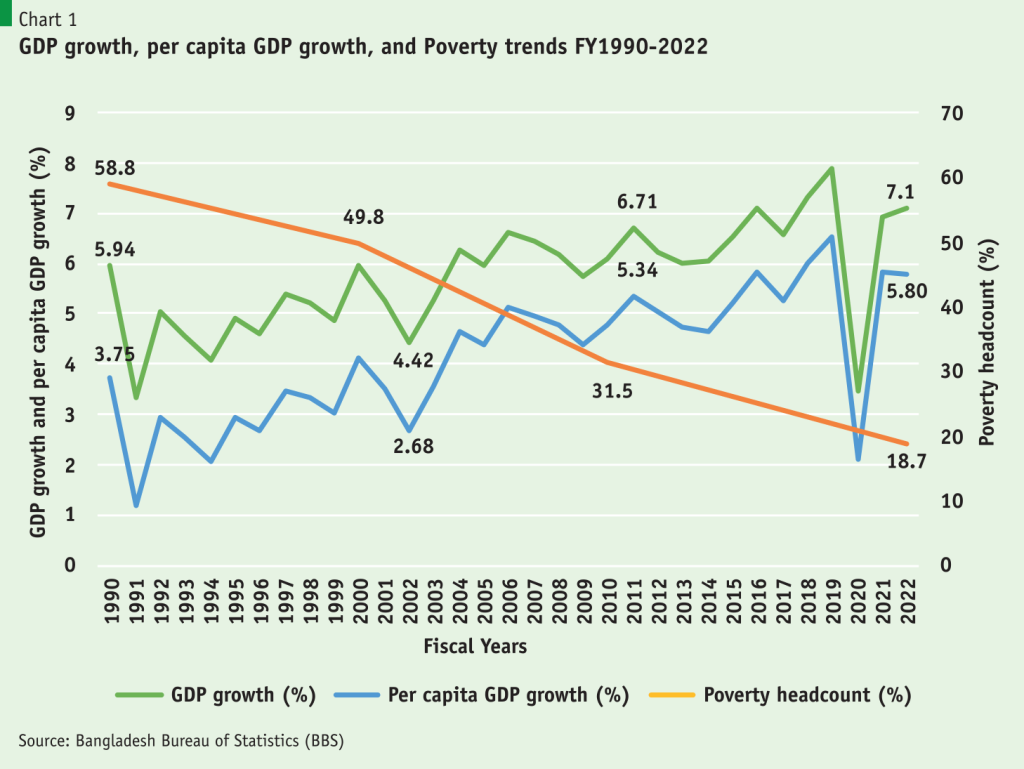

True, not everything has gone the way it could for a nation that suffered from a massive food deficit with 70 million mouths to feed at independence in 1971. Analysts who have monitored progress from the inside could argue that due to opportunities lost along the way development has fallen short of potential for this nation of 170 million people today. Yet, the truth is that Bangladesh has nearly obliterated extreme forms of poverty while acquiring tremendous expertise in disaster preparedness and management. Currently, poverty is at a historical low, at 18.7% in 2022 (Table 1), what used to be over 75% in the 1970s, the latter situation gave Bangladesh the label of a ‘poor country’. Slowly but surely, that label has started to wear off as the country crossed the threshold of a lower middle-income country (LMIC, by the World Bank income classification) in 2015 and is on course to graduate out of LDC status in 2026.

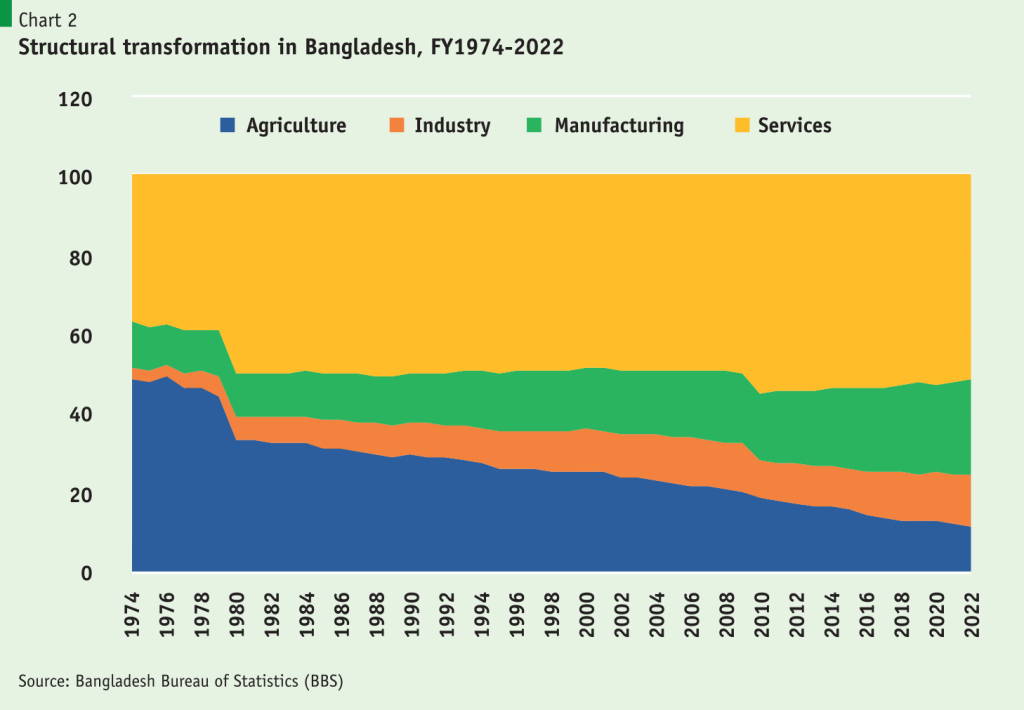

While GDP growth has been rising by roughly one percentage point every decade, averaging 6.4% in FY2011–FY2020, poverty has been on the decline as well, falling from 59% in 1990 to 18.7% in 2022 (Table 1, Chart 1). Meanwhile, the economy has been going through structural transformation which fits in with the stylized facts of development: the share of industry in GDP has grown from 17% in 1980 to 37.5% in 2023, while the share of agriculture has fallen steeply from 33% to 11% during the same period. The service sector, which is largely informal, has remained steady at around 51%–54% of GDP. Most notable is the rise of the manufacturing sector, largely driven by superior export performance, which rose from 11% of GDP in 1980 to 25% in 2023. There is no tendency towards de-industrialisation that is the feature of many other developing economies. Currently, almost 50% of manufacturing value added comes from export-oriented production.

So, what is the secret of Bangladesh’s success story?

So, what is the secret of Bangladesh’s success story?

Nexus of Trade and Bangladesh Development

Among other attributes, trade and industry have been key drivers of Bangladesh’s development phenomenon (Sattar, 2023) that was thankfully premised on Comparative Advantage Following (CAF) strategies: e.g. the case of readymade garments.

Throughout history, trade has been the lifeline of nations and communities and a powerful driver of economic growth and poverty alleviation. Among others, a trade-led strategy of development has been at the core of Bangladesh’s record of economic progress of the past 30 years. It was in the 1990s decade that Bangladesh made the ‘leap of faith’ into the world of trade openness by switching from an inward-looking import substituting trade strategy to an outward looking export-oriented regime which earned it the title of ‘globaliser’ among developing economies (Trade, Growth and Poverty by Dollar and Kraay, World Bank, 2001). World Bank research confirmed that economies that globalised grew faster than those that did not. Bangladesh economy has continued to reap the benefits of the regime switch in terms of export growth, job creation, and poverty reduction.

Among others, a trade-led strategy of development has been at the core of Bangladesh’s record of economic progress of the past 30 years.

The case for export-oriented development came out strongly in the report of the Growth Commission set up by the UN in the early 21st century and led by Nobel Laureate Michael Spence. One important conclusion that came out of that research was that unlike in the past centuries, developing economies could now grow at rates of 7,8,9, or 10, by leveraging demand in the global marketplace, something the domestic market cannot offer. Trade economists like Anne Kruger argued strongly that the domestic market of most developing economies was too small to offer the kind of scale economies that the global economy can provide. The global market is just too big so that no single country can affect world prices. That means, basically, that you can export and grow as fast as you can invest, provided you have some competitive edge. East Asian countries, eager to develop rapidly, realised this early on in the 20th century. And East Asian economies (e.g. China and Vietnam) continue to show the world new variants of export-led growth in the 21st century. Bangladesh was able to build on that experience.

After some prevarication Bangladesh policymakers embraced trade and export-led growth strategy which yielded the greatest benefits via export and GDP growth over the past three decades. Actually, we are now demonstrating to the world our own version of export-led growth, the Bangladesh way.

True, Bangladesh’s export success has been limited to one manufacturing product group – readymade garments (RMG) – but that is in itself a major transformation for an economy that began exporting only primary products like jute, tea, and shrimps in the 1970s. Putting a densely populated developing economy on the world map of manufacturing exports was itself a validation of the fundamental proposition in international trade – gains from trade based on a nation’s comparative advantage which in turn is driven by factor (resource) endowments. It was strong confirmation of the time-tested principle of comparative advantage laid out by classical economists Smith-Ricardo-Mill.1 Apparel making was a labour-intensive activity and Bangladesh’s abundant cheap low-skilled labour was just the resource needed to produce and exchange competitively in the world market. But that also needed creation of a level playing field in the world marketplace. That is where multilateralism and Bangladesh’s trade regime comes into play.

The strategy of export-led growth built on the back of trade liberalisation policies had finally taken hold in the policy space. The liberalising reforms of the 1990s, albeit incomplete, generated enough momentum to stimulate export-oriented manufacturing growth, job creation, and poverty reduction for the next two decades, and the momentum continues to this day. Like everywhere else, the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic and ramifications of the Russo-Ukraine war clearly disrupted the steady path of economic progress as well as poverty reduction during 2020–2023, but there are signs that Bangladesh economy has built enough resilience to cope with the current externally driven challenges to steer the economy through a rejuvenation of its export strategy in order to return to its pre-pandemic growth path.

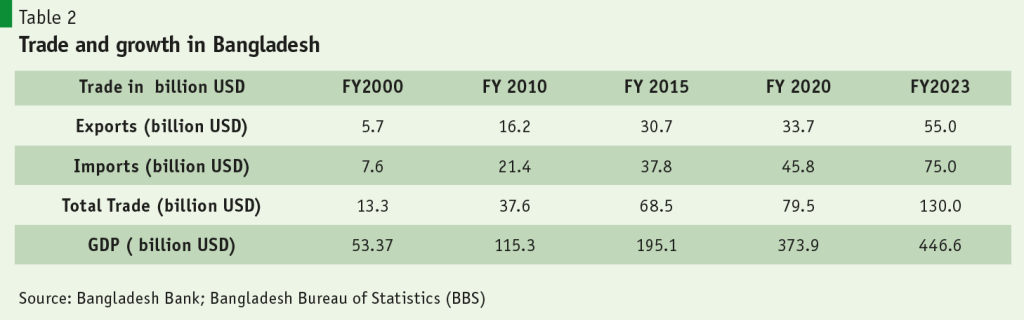

Still, there is much to cheer about. Thus far trade and output growth in the Bangladesh economy have grown in tandem with each other (Table 2). Merchandise exports, imports, and total trade in FY2023 have grown to ten times what they were in FY2000. Exports, imports and trade averaged annual growth rates of 11%, 13%, and 12%, respectively. GDP has been rising (in size and growth) alongside this trade phenomenon. Planning and performance of the last decade were evenly matched thanks to the government strategy of facilitating rather than interfering in private business and investment initiatives.

In the year 2023, just past the 50th anniversary of Bangladesh’s independence, the economy stands at a historical inflexion point. It is the ideal turning point in the country’s history to launch a major reform initiative in the realm of trade policy to instil the kind of growth momentum that was experienced by economies in East Asia over the past 70 years. The momentum is clearly evident. It has the potential to grow at sustainable rates of 7% plus. But opportunities opening up in the global marketplace of the 21st century must be seized through aggressive trade and supportive economic reforms, like the East Asian economies did and are still doing, if Bangladesh is to live up to the reputation of resilience and dynamism that it has earned so far, defying the geopolitical doomsayers once and for all.

Opportunities opening up in the global marketplace of the 21st century must be seized through aggressive trade and supportive economic reforms, like the East Asian economies did and are still doing, if Bangladesh is to live up to the reputation of resilience and dynamism that it has earned so far, defying the geopolitical doomsayers once and for all.

Here is the million-dollar question being asked around academia and policy making circles. Can Bangladesh sustain its growth performance on the back of one single industry group, readymade garments (RMG), as the premier driver of growth?

DRIVER 1:RMG Success Relies on Trade Policy Dualism in Bangladesh

Exporters of Bangladesh are governed by different sets of rules depending on whether they belong to the 100% export-oriented RMG sector or the rest. The provision of special bonded warehouses (SBW) for stocking duty-free imported inputs, back-to-back letter of credit (LC) mechanism that facilitates imports of inputs on credit against master export LCs, and ‘green channel’ import-export customs clearance make RMG sector operate in something of a ‘free trade enclave’ in an otherwise high-tariff and restrictive import regime. While quotas under the now defunct Multifibre Arrangement (MFA) gave Bangladesh RMG producers initial market access, that is not the whole secret of RMG success. I would argue, based on principles of trade theory and policy, that it was the free trade arrangement that provided the right impetus for global success in an industry that fitted squarely with Bangladesh’s competitive advantage in low-skill intensive manufacturing. Other exporters (who are not 100% export-oriented) are not so privileged and must plough their way through the cumbersome tariff and duty-drawback regime often coupled with many burdensome regulations as well.

Bangladesh could benefit hugely from a radical change in this policy area. Why?

High and persistent tariff protection is the problem. Trade economists have long argued that export performance and tariff protection are not mutually exclusive. Tariffs on import substitute production are indirect subsidies that undermine support to exports and create anti-export bias. Having carved out a virtually free trade regime for the 100% export-oriented RMG sector, by ensuring world-priced inputs through the SBW system, there seems to be too much internal resistance to the replication of this regime for the non-RMG exports. A trade economist would argue that the protectionist lobbies appeared insurmountable to create an RMG-like regime for some 1600 (HS-6-digit) non-RMG export products that Bangladesh exported annually.

Consequently, despite evidence of potential comparative advantage, non-RMG exports got no traction, continuing to remain in the shadows of RMG exports that continue to dominate the export basket (84% of exports). The evidence is strong that these non-RMG exports which are not 100% export-oriented – in the sense that its producers cater to the domestic as well export markets – find profitability from the highly protected domestic markets relatively higher. Result: with all its flaws Bangladesh’s claim to export success is built on the record of the readymade garment industry.

The enclave system The fact is Bangladesh’s leading and most successful export sector – RMG – is virtually unaffected by the anti-export bias of the tariff regime. Why? From the very beginning, RMG industries evolved within a sort of ‘free trade enclave’ that essentially neutralised an otherwise high tariff regime through the institution of SBW to ensure duty-free imported inputs. Supporting facility of back-to-back LC system provided much needed access to working capital in foreign exchange. Later, once RMG became the leading export, it was given high priority for port clearance and other administrative processes. The RMG industry thus developed as a 100% export-oriented sector, not in competition with other manufacturing geared to domestic sales. However, other exports were not as privileged as they had to cope with the high tariff regime while importing required raw materials and intermediate or capital inputs. The dysfunctional duty drawback system was no match to the SBW facility. Neither were export subsidies (5%–25%) in comparison to high protective tariffs (56%–128%), which were tantamount to indirect subsidies to import substitutes.

So when non-RMG manufacturing producers compared relative incentives between exports and domestic sales, they found significantly higher profits in domestic sales. In a recent study carried out by PRI (2023), which measured anti-export bias of incentives, it was found that incentives were significantly higher (26%–67%) for import substitutes that were declared as ‘thrust sectors’, or ‘priority sectors’, such as footwear, home textiles, light engineering. That meant that whereas processing margins were close to free trade margins for exports, they were significantly higher for sales in the domestic market. This is how the trade policy regime reveals an anti-export bias for non-RMG exports thus discouraging emergence and expansion of new products in Bangladesh’s export basket.

Bangladesh RMG industry has come of age and is now a global player, highly price competitive as well as quality competitive when it comes to basic garments, knitwear, and cotton products. It now has a notable presence in the world market not to be ignored by buyers, retailers and consumers, in Europe, North America and Asia. Lately, RMG exports to non-traditional markets in Asia-Pacific (Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Middle East) have been growing faster than traditional markets. The future potentials of RMG exports in the world market have not been fully exhausted. There is a long way to go.

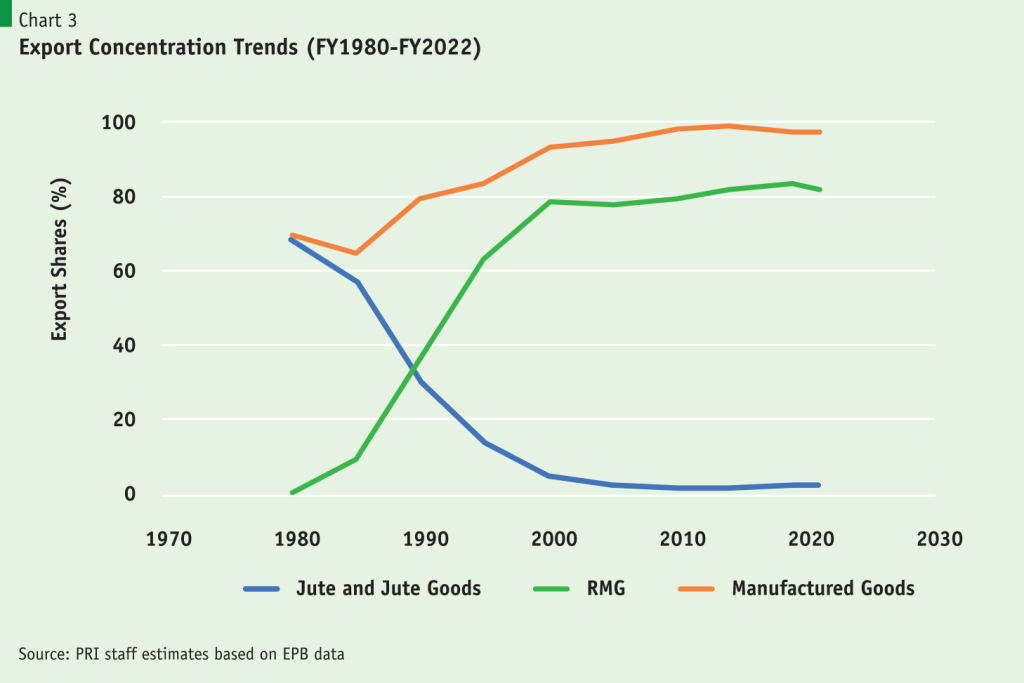

But other exports lag behind stalling export diversification Bangladesh has managed to surpass the stage of vertical diversification, as manufactured exports overtook primary exports such as jute, jute goods, and tea in the early 1990s. For several decades, Bangladesh experienced export concentration, primarily dominated by jute and jute goods, accounting for 70% of exports in 1981. However, by 1990, RMG exports had surpassed jute exports, and by the late 1990s, a renewed concentration in exports emerged, with RMG exports reaching a share of 77% by FY2000 (Chart 3). Now, RMG share in exports hover around 82%–84%.

Some important non-traditional exports like footwear and leather products, light engineering products (bicycle and electronics), pharmaceuticals, ceramics, jute goods, plastic toys and miscellaneous products, and many labour-intensive products not yet on the export radar, are likely to grow at a much faster rate if the anti-export bias of trade policy can be removed. Export diversification should be a key objective underlying the future strategy for manufacturing growth. Before the emergence of RMG exports, jute and jute goods dominated the export sector for many decades making up 70% of exports until 1981. By 1990, RMG exports overtook the traditional export, but its concentration in the export basket, which has risen to 83%, added a new dimension of export vulnerability. Export diversification has become a major challenge for future trade policy. While Bangladesh’s export growth for the last decade and a half could be characterised as robust, a sudden decline in demand for Bangladeshi RMG would send shock waves throughout the economy. Such a prospect can be avoided through the creation of a diversified export basket.

With the labour cost advantage that Bangladesh enjoys, there seems to exist good prospects for extending into exports of labour-intensive products other than RMG such as agro-processed industry, food products, other manufactures (e.g. electronics and auto parts) and assembly operations. By broadening the range of exported items and export destinations, diversification can stabilise and expand export revenues, enhance value added, and boost economic growth.

Bangladesh experienced double digit export growth over the past two decades. Yet this superior performance is overshadowed by the fact that the increase was mostly due to one product group – readymade garments. The empirical analysis of export trends in Bangladesh reveal lack of product diversification which has remained practically unchanged, if not slightly worsened, for the past two decades. This contrasts with progress in export diversification attained by most developing countries. Research suggests that some 60% of developing countries managed to diversify their export baskets to some extent over the past 25-30 years.

The sooner we can make our tariff structure reflective of a dynamic export-oriented economy the better our chance of diversifying our exports with a bustling diversified export-driven manufacturing sector that creates jobs and income to win the war on poverty. This is exactly the strategy laid out in the Government’s 8th Five Year Plan (FY2021–FY2025).

The sooner we can make our tariff structure reflective of a dynamic export-oriented economy the better our chance of diversifying our exports with a bustling diversified export-driven manufacturing sector that creates jobs and income to win the war on poverty.

It would be a fair assessment to suggest that Bangladesh energetically launched first generation trade reforms in the 1990s and is still reaping the benefits of those reforms in terms of export, growth and poverty impacts.

But tariff reforms, one critical ingredient of trade policy, still remain largely unfinished with some ossification evident in recent times. Can the economy achieve its medium-term and long-term goals without modernising its tariff structure? The fact that the current tariff regime is a ‘binding constraint’ to the realisation of export diversification – a priority development agenda of the Government – is now confirmed through research and recognised at the highest levels of Government. A National Tariff Policy 2023 (NTP 2023) has been launched that aims to modernise the tariff structure such that it supports rather than impedes dynamism of the Bangladesh economy going forward.

Nevertheless, the dominance of RMG exports prevails, and this is likely to continue for at least another decade before non-RMG exports start becoming just as important. Nevertheless, there are two positive developments on the diversification front within RMG. First, there has been growing diversification of products, from lower-end to higher end, with movement from cotton-based products to manmade fibre (MMF) products, which are the fastest growing segment of RMG. Second, geographical diversification – expanding destination markets beyond Europe and North America to the Asia-Pacific and Middle East region – is taking deep roots, quite rapidly. Prospects in Asian markets remain bright in the future.

Throttling anti-export bias to open doors for export diversification Begin with the recognition that we have essentially two trade policy tracks, one for RMG exports and another for the rest. RMG operates in a ‘free trade’ enclave (zero tariffs), nearly immune to the high tariff and protection regime that creates significant anti-export bias for non-RMG exports. That is the crux of the problem. This trade policy dualism has got to change. Unless trade policy for non-RMG exports is brought to par with RMG, export diversification has no chance. Until such time as we can unify the two tracks of trade policy, our only option is to revamp the twin tracks of trade policy, along the following lines:

First, the biggest challenge to export diversification comes from the high protection regime in the domestic economy. The problem with non-RMG exports (firms are not 100% exporters), like footwear, plastic, agro-processing products, light engineering, is that domestic tariff-induced protection is so high, making domestic sales so profitable, that exporting is not an attractive option. To get any traction on export diversification, this incentive system must be turned around. The overarching challenge in future trade policy lies in making all exporting activity more attractive than selling in the domestic market. The NTP 2023, announced in August 2023, has all the right ingredients to throttle anti-export bias and achieve that objective.

Second, prepare a vigorous plan for geographical diversification to break into new markets in East Asia and the Pacific (e.g. China, Japan, S Korea, Australia, New Zealand, RCEP countries).

Third, all out measures will have to be undertaken to enhance export competitiveness, based on comparative-advantage-following (CAF) strategies, including improved trade infrastructure, access to finance, ease of doing business, and so on. Until such time as the two trade policy tracks are brought to par with each other, all non-RMG exporters will have to be given facilities to get world-priced (zero-tariff) imported inputs in order to compete on a level playing field (see NTP 2023).

Fourth, while recognising that RMG export prospects globally are not fully exhausted, efforts should continue to improve competitiveness by raising quality, efficiency, productivity, and compliance in the RMG sector and its backward linkage industries. Strategies for diversification within the RMG industry (e.g. going beyond basic garments to higher value items, expanding man-made fibre (MMF) exports) ought to be pursued with vigour and policy support.

Fifth, as part of the export diversification strategy, diversify into intermediate goods production for exports (e.g. automotive and electronic parts and components) by vigorously seeking FDI to integrate with global value chains (GVC). Emulating Vietnam’s experience would be worthwhile.

Finally, robust export performance requires two common traits for the exchange rate: (a) flexibility, and (b) strict avoidance of overvaluation. Recognising that it would be well-nigh impossible for the economy to export and grow its way out of the COVID-19 slump with an overvalued exchange rate, the crisis presents a timely opportunity for ‘compensated’ depreciation of the exchange rate (e.g. depreciation associated with complementary measures to neutralise inflationary or other negative effects) to give a boost to post-pandemic export performance and its diversification. One strategy for ‘compensated’ depreciation would be to reduce tariffs by about the same percentage as the central bank lets the exchange rate depreciate in a year (such as a 5% reduction in tariffs equivalent to a 5% depreciation of the exchange rate, an action that will essentially eliminate the inflationary price effects leaving import revenue unchanged).

DRIVER 2: Remittances –– the Export of Factor Services

That said, it is important to highlight another key driver of the Bangladesh economy – copious amounts of remittances from migrant workers, second in volume to our export of merchandise goods. Indeed, foreign exchange inflows from remittance cannot be differentiated from foreign exchange earnings from RMG and non-RMG exports. Remittance is another term for export of ‘factor services’, which also takes place under the rules-based global trade order – General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), mode 4. With remittance making up as much as 5%–6% of GDP, Bangladesh is a major participant in the global trade in services.

Harnessing remittance flows for development Remittance, the income and savings of migrant workers, is unquestionably a strong driver of growth via its impact on consumption and investment spending as well as its singular contribution to Bangladesh’s sustainable current account balance in the wake of rising demand of foreign exchange for import of goods and services to meet development requirements.

Cross-country research evidence confirms that remittances from migrants have positive impacts on poverty reduction and development in originating countries, mostly developing ones, substantially contributing to the achievement of development goals. These positive impacts become greater when remittances can be saved and invested in infrastructures and productive capacity. Government policy measures could induce such use. So significant barriers to migration and remittance transfers in Bangladesh need to be addressed in order to harness opportunities for development and poverty reduction, including through easing financial transfers, setting appropriate incentives, improving policy coherence in migration and remittances policies, and facilitating the temporary movement of people.

So significant barriers to migration and remittance transfers in Bangladesh need to be addressed in order to harness opportunities for development and poverty reduction, including through easing financial transfers, setting appropriate incentives, improving policy coherence in migration and remittances policies, and facilitating the temporary movement of people.

Remittance and Exports – twin sources of development finance It is important to consider the impact of the two mediums of foreign exchange earnings for Bangladesh that started to show promise since the 1990s. Together they account for 20% of GDP, driving consumption, investment and job creation. Steady flows of remittances from migrants have had important stabilising effects on the balance of payments. The chronic trade deficits resulting from the import-dependent development programs that arguably involves rising imports of machinery, capital goods, and industrial raw materials, has been regularly offset by consistently rising remittance inflows to yield current account surpluses for 13 years since 2001. Remittances have contributed significantly to the sustainability of our external balance thus facilitating accumulation of foreign exchange reserves.

DRIVER 3: Rise of Agriculture and Approach to Food Self Sufficiency

It would be a mistake to ignore the contribution of agriculture in the Bangladesh story. Bangladesh began its journey in 1971 as a food deficit country with 70 million mouths to feed, with 10 MMT of rice production which was 10% short of domestic requirement. The deficit was met with food aid and imports. Food aid is now history having disappeared from the radar in the 1990s.

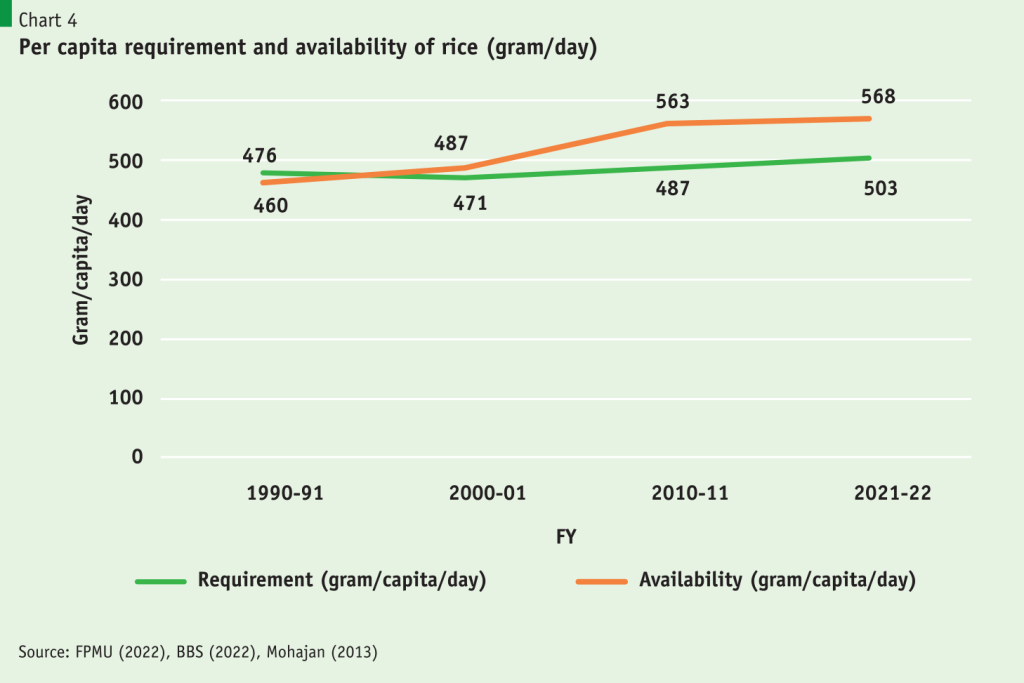

In the past five decades, both rice output and productivity (MT/ha) quadrupled. Rice (the staple food) production has quadrupled to over 40 MMT in 2023 while population rose 2.5 times to 170 million, making the country nearly self-sufficient in food.2 Indeed, since 2001, the government has been proactively keeping per capita availability of rice above requirement (holding adequate quantity in storage to meet emergencies) so that per capita availability has exceeded requirements (Chart 4) for all of the past two decades to keep any shortage at bay.3 Rice production shifted rapidly from traditional varieties to high yielding varieties (HYV) in a matter of two decades with the main crop shifting from Aman (now 40%) to HYV Boro (now 60%) with use of fertiliser, seeds and irrigation, and adoption of mechanisation in various stages of production.

Though ongoing, there was something of a mini-green revolution which ensured food security to the country while trade and industry drove rapid economic growth.

The prime movers in this remarkable turnaround in the agricultural sector and in food supply were government policy support and private enterprise activity in turning agriculture from an entirely subsistence activity to a quasi-commercial farm and non-farm enterprise. Moreover, the cultivation of HYV and climate-resilient rice varieties, including those tolerant to drought, submergence, and salinity, has played a vital role in enhancing rice production. Superior public disaster management (in handling regular floods and natural calamities) also helped build resilience in ensuring stable domestic food supply.

There was another critical driver of productivity in the agricultural sector. Agricultural input market liberalisation in Bangladesh in the 1980s was a transformative policy shift aimed at reforming the country’s agricultural sector (Ahmed, 1995). Prior to that, Bangladesh’s agricultural sector was heavily regulated and controlled by the government as it played a central role in the production, distribution, and pricing of agricultural inputs like seeds, fertilisers, and pesticides.

The liberalisation process involved reducing the government’s direct involvement in the agricultural input markets. This included allowing private sector companies to import, produce, and distribute agricultural inputs (fertiliser, seeds, farm implements), fostering competition and market-driven pricing. The results have been phenomenal, changing the skyline of not only agriculture but the overall economy.

DRIVER 4: NGOs as Driver of Social Change and Human Development

The Bangladesh story would remain incomplete without an acknowledgment of the critical role of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) in its development.

A pivotal force behind Bangladesh’s remarkable progress in various social indicators, particularly poverty reduction, improved health and education outcomes, and rural income growth, has been the concerted efforts of NGOs. These organisations have played a central role in implementing effective social action initiatives, complementing the government’s endeavours. They have been critical in empowering women through microfinance initiatives, reducing infant and maternal mortality rates, and promoting education in rural areas. Furthermore, NGOs have been influential in disaster relief and climate adaptation efforts, which are increasingly essential in a country vulnerable to climate change impacts. NGOs have not only contributed to improving the lives of millions but have also showcased the potential of civil society organisations to drive positive change in human development outcomes.

A pivotal force behind Bangladesh’s remarkable progress in various social indicators, particularly poverty reduction, improved health and education outcomes, and rural income growth, has been the concerted efforts of NGOs.

One of the standout successes in Bangladesh’s development story is the delivery of accessible and effective health services. While the government has certainly expanded healthcare services, the most dynamic and widespread impact has come from NGOs. BRAC (originally the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee), in particular, has been a driving force.

In addition to healthcare, Bangladesh has witnessed significant advancements in education, welfare programs, and targeted credit initiatives. What sets Bangladesh apart, as observed by Stefan Dercon (2022) in his book Gambling on Development: Why some countries win and others lose, is that ‘this expansion has been primarily driven by local NGOs, and in no other developing countries have indigenous development organisations, set up explicitly to support poor populations, had such an impact’. These NGOs have been instrumental in delivering education to underserved populations, fostering welfare programs, and facilitating access to credit for those in need. Their tireless efforts have not only transformed individual lives but have also contributed significantly to Bangladesh’s impressive human development journey.

A mature, sensible state Few people studying development would claim that the state does not play a role in it, but there are huge differences in how much the state takes on in the quest for development. This is true even in successful cases, as well as in failures. Success requires finding a balance between what the state should do and what it can do—and local circumstances will dictate what this is.

However, NGOs could not have achieved what they did without the express support of the government. So, in all of the NGO-driven progress that we see, the tacit concurrence of government was pervasive, partly to bridge the gap between government’s own limited capability and the tremendous need for health and education services, particularly at the grassroots level, The NGO success story is part of the government’s commitment to deliver social services by whatever suitable means possible. Bangladesh remains a unique example of GO-NGO partnership for delivery of health, education, and social protection outcomes that are vital ingredients of development.

When it comes to health-education service delivery, Bangladesh may be described as a laissez-faire developmental state in which NGOs fill the gaps left by the state. Literacy rate has reached 74% from 22% in 1974, gender parity has been achieved in primary and secondary education along with near universal access to primary education– within a span of 50 years, all in an environment of serious governance deficit. That is the Bangladesh surprise.

DRIVER 5: Aid as the Catalyst

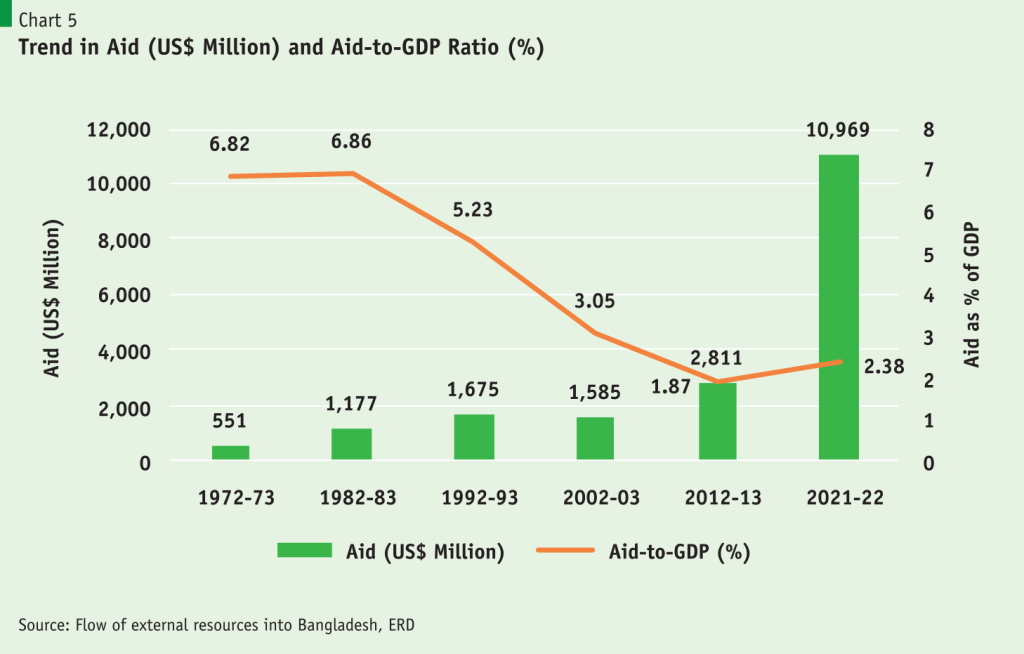

Bangladesh, often described as a messy state but one with the necessary structures in and outside government, has a record of spending well and to benefit from aid. Bangladesh is not only a story of development success but also a model of development cooperation. Since independence, the country has been receiving significant amounts of official development assistance (ODA), which rose from USD 8 per capita in 1972 to USD 65 in 2022. Throughout this period of development progress, the reliance on aid has been falling, from 6.8% of GDP down to 2.4% (Chart 5) – a crucial sign of aid effectiveness. In FY2023, 94% of outstanding public external debt of USD 70 billion was concessional debt, with an average interest rate of 1.3% and repayment period of 23 years. Annual debt servicing is under 5% of its foreign exchange earnings revealing strong debt carrying capacity, as determined by World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis.

Though not perfect, Bangladesh presents a notable example of effective aid utilisation where ODA has been a catalyst for its rapid progress. The World Bank calls Bangladesh ‘an inspiring story of reducing poverty’ – 25 million people lifted out of poverty in 25 years.

China+1: Opportunities, Challenges, and Sustainability of Growth

Of the four drivers of Bangladesh’s success story, China+1 creates opportunities and presents some challenges for the RMG sector.

Bangladesh has become a global player in the world market of readymade garments. Prospects are bright that it will maintain its position at least until 2031, when it is expected to cross the upper middle-income country (UMIC) threshold. RMG will continue to be a key driver of Bangladesh’s growth.

The sourcing of RMG is experiencing a new phase of transition, as the geopolitical order unfolds in the wake of ‘China+1’, which is creating the need for companies to react accordingly in order to secure their cost positions in the apparel market. While China was once considered ‘the place to be’ for sourcing, the light is starting to shine ever brighter on Bangladesh. When it comes to the future of sourcing, there appears to be a radical shift away from China.

McKinsey Global reports that at least USD 100 billion out of the USD 625 billion apparel market in 2030, will move away from China, in light of shifting geo economic and geopolitical order, on top of the already rising wage costs in China. Since 2020, China has lost a quarter of its RMG exports as buyers look desperately for alternatives. China exported USD 182 billion of apparel in 2022 (31% of world exports) while Bangladesh edged up from a share of 6.4% to 8% in 2022.

For many years, China was almost always the hands-down answer to all buyers’ needs, but those times are changing. No longer China is ‘the place to be’. Buyers are making sourcing strategy revisions based on five considerations: price, quality, capacity, speed, and risk. Bangladesh offers the two main ‘hard’ advantages – price and capacity. It provides satisfactory quality levels, especially in value and entry-level mid-market products (called basic garments), while acceptable speed and risk levels can be achieved through careful management. For the next ten years, McKinsey forecasts a continuation in the high growth of Bangladesh’s RMG sector and Bangladesh looks to be the sourcing country of choice for 90% of Chief Procurement Officers (CPOs) of leading buyers in the US-EU.

Bangladesh must position itself to accommodate the new sourcing strategies away from China. Leave it to Bangladesh’s first generation entrepreneurs and see them rise up to it. Over the past decade, Bangladesh’s RMG sector has made impressive progress in tackling the challenges of growth—particularly in diversifying export destinations and products, improving supplier and workforce performance, and strengthening compliance and sustainability. The sector’s participation in new initiatives regarding climate change and circularity have advanced the sustainability agenda, for example, through the Circular Fashion Partnership, a multi-stakeholder initiative aiming to scale up recycling of production waste.

Bangladesh’s garment sector has every prospect of remaining one of the world’s largest RMG manufacturers and continuing its impressive story of growth and improvement. All indications are that Bangladesh’s medium-term prospects will ride on the fortunes of this one sector.

But beyond 2030 the country must be prepared for a new ball game of even tougher competition for survival and prosperity. For Bangladesh, the challenge will be to spot the opportunities in the evolving global order, build competitiveness, and continue to leverage the global marketplace for future export growth. That calls for economic diversification for which radical changes in direction will have to be made now.

To continue succeeding, Bangladesh needs to update the business mindset and the policy approach. The preparation should begin now, as the country – the largest LDC – approaches graduation in 2026. To secure a prosperous future, Bangladesh needs to prioritise new drivers of growth. It needs to shift from a price-led competitiveness model to one grounded on quality and innovation. But that is easier said than done. Radical increases in health and education expenditures as a share of GDP must be made to catch up with comparators with a sharp focus on up-skilling the workforce of the future.

Macroeconomic stability and future growth While the Bangladesh economy was posting a strong post-Covid recovery, the economy was struck by the aftermath of the Russo-Ukraine war that caused significant stress on the country’s balance of payments, depleting foreign reserves, like many other developing and emerging economies. But prudent macroeconomic management, both internal and external, for the previous three decades had built strong foundations for resilience against such external developments. Since the 1990s, inflation has been moderate and steady, fiscal and current account deficits have been in sustainable range, and external debt remained impressively moderate (confirmed by recent Debt Sustainability Analysis of World Bank-IMF). Nevertheless, in the wake of balance of payments stresses arising out of external shocks, an IMF program is currently underway that should help contain inflation, stabilise the balance of payments and shore up foreign exchange reserves to set up the economy for a resumption of its past trajectory of growth with stability. GDP growth, which moderated to 6% in FY2023 is expected to continue at a respectable 6.5%–7% over the next three years, according to projections of the multilateral agencies.

Leveraging the G20 module for sustainable and inclusive growth Bangladesh is a strong beneficiary of a globalised world of interconnectedness and gainful interdependence via trade and investment. In pursuit of its past legacy, Bangladesh stands to gain from its continued commitment to its classical stance of international diplomacy guided by the dictum of ‘friendship to all and malice to none’. In this regard, India’s current presidency of the G20 with the theme of ‘One Earth, one family, one future’, suitably jibes with Bangladesh’s foundational political stance. Bangladesh’s long-term focus on international trade and investment are also in line with the trilogy track of global macroeconomic stability, environmental sustainability and climate resilience, and multilateral reforms for globally inclusive, equitable and sustainable growth that are part and parcel of G20 goals under India’s presidency.

Bangladesh looks forward to continued association with this select group of large and consequential economies of the world in the hope of accessing global markets in a level playing field under a rejuvenated rules-based and inclusive global economic order. Furthermore, Bangladesh looks forward to receiving the support of G20 leaders in getting access to climate funds that will be available for ‘loss and damage’ compensation in the short-term along with prospects of long-term financing of Bangladesh’s adaptation and mitigation goals.

References

Ahmed, R. (1995). Liberalisation of agricultural input markets in Bangladesh: Process, impact, and lessons. Agricultural Economics, 12(2), 115-128.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) (2022). Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Dercon, Stefan (2022). Gambling on Development: Why some countries win, and others lose. C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London.

Food Planning and Monitoring Unit (2022). Database published in Directorate General of Food, Ministry of Food, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, http://fpmu.gov.bd/fpmu-database/Section%205.htm

Mohajan, H. (2013). Food and nutrition of Bangladesh. Peak Journal of Food Science and Technology, Vol.2 (1), 1-17.

Ministry of Commerce (2023). National Tariff Policy 2023. Bangladesh Trade and Tariff Commission.

Sattar, Z. (2023). Trade and industry in 21st century Bangladesh. WhiteBoard, Issue 12.

Sattar, Z. (2021). The Rise of Readymade Garment Industry: Still a Beacon of hope for Bangladesh. The Apparel Story. 40 Years of BGMEA.