FY2025 National Budget for Macroeconomic Stability

By

Over the past two years Bangladesh has been facing serious macroeconomic instability reflected in high inflation, depleting foreign reserves, pressure on the exchange rate, declining capital inflows and pressure on the budget. In response, the government has devalued the currency, imposed import controls, tightened public spending and very recently it has allowed interest rates to increase. The full range of demand management policies that is necessary to reduce demand and stabilise the economy has not yet happened. Consequently, macroeconomic imbalances continue to persist.

The monetary policy response allowing interest rate to increase to stem the growth of domestic demand came late in the day, starting in September 2023. Nevertheless, since September 2023 Bangladesh Bank (BB) has stopped financing the Treasury deficit through money creation. Most importantly, it formally abandoned the controversial ‘6/9’ interest rate policy that set ceilings on deposit (6%) and lending (9%) rates. Now there is no limit on deposit rates and lending rates are flexible, set by the market on the basis of 3 plus premium over the six -month average treasury bill rate. Since the T-bill rate is flexible, the lending rate is also flexible.

While the flexibility of the interest rate has already reduced the demand for credit and lowered the demand pressure on the foreign exchange, the impact on reduction in the inflation rate has been less visible. This is partly because of the time lag, but also because the demand pressure emanating from fiscal deficits has not been addressed. Despite significant cutbacks in annual development spending, the budget deficit remains stubbornly high at around 5% of GDP owing to shortfalls in tax revenue mobilisation. While a fiscal deficit of 5% of GDP may not appear high in a normal year, in the present context of high inflation and pressure on the balance of payments there is a need to contain the fiscal deficit to 2–3% of GDP. This is particularly important to avoid putting all the pressure of adjustment on interest rate and private credit. Government domestic borrowing required to finance the fiscal deficit must also be contained.

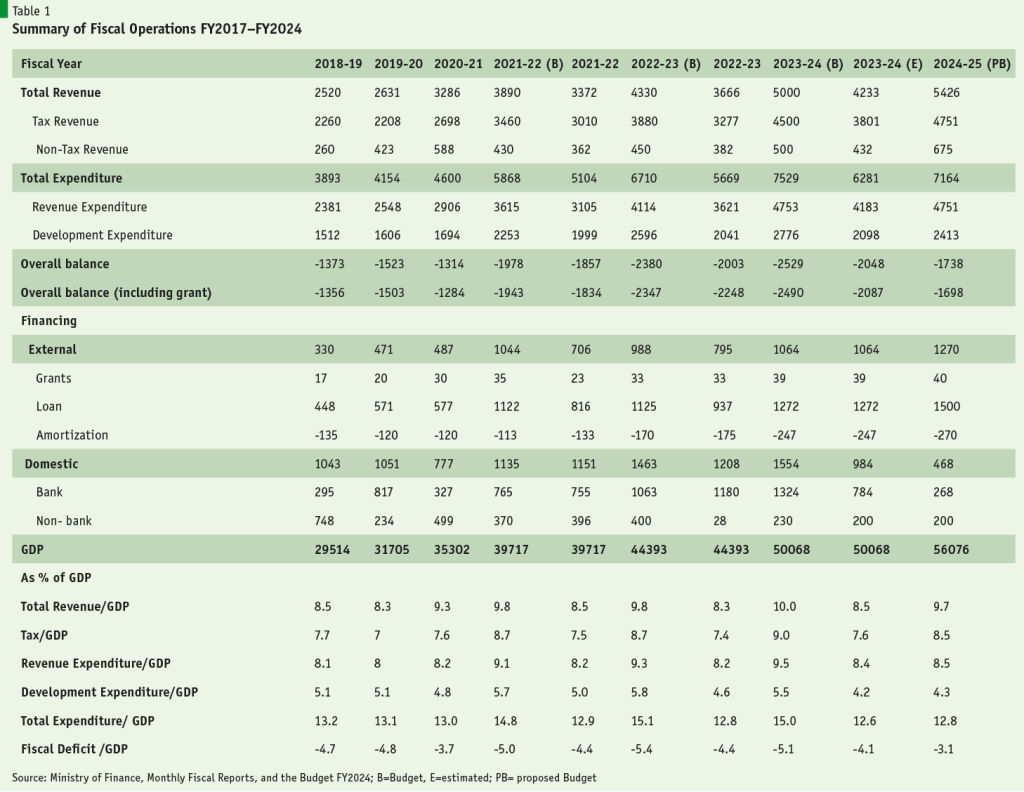

Two years in a row, fiscal policy failed to address the stability problem. But the forthcoming FY2025 presents an opportunity. How would a budget that supports macroeconomic stability look like? The summary structure of such a budget is illustrated in Table 1. The numbers for the proposed FY2025 Budget (PB) are illustrative. The important points are the underlying budget strategy and associated reforms. The main elements of the budget strategy should be to reduce fiscal deficit significantly to lower aggregate demand. This demand reduction should be achieved in a way that it does not compromise the future growth prospect or reduce equity. For this to happen, the strategy involves raising tax revenues through effective tax reforms, increasing the profitability of State Owned Enterprises (SoEs) through corporate governance and pricing reforms, reducing subsidies and increasing spending on human development and social protection. The numbers in Table 1 illustrate how this can be possible.

The main elements of the budget strategy should be to reduce fiscal deficit significantly to lower aggregate demand. This demand reduction should be achieved in a way that it does not compromise the future growth prospect or reduce equity.

Increasing tax revenues through focused tax reforms: Instead of ad-hoc tax measures with uncertain revenue prospects, Table 1 assumes that the government will start implementing a focused medium-term tax reform program. The Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI) has done considerable research on the tax reform agenda. So, the main elements of the tax reform are well known and have been presented in public fora and shared with the government many times. These include i) separating tax planning and tax policy from tax collection; ii) substantially strengthening both units with autonomy, professional management and quality staffing; iii) digitising tax assessment and collection thereby eliminating the interface between taxpayer and tax collector; iv) simplifying tax filing by eliminating the income, expenditure and wealth reconciling; v) selective and productive audits done by professional auditors; vi) implementing the 2012 VAT Law; and vii) introducing a modern property tax system.

While the full implementation of the tax modernisation plan will take 2–3 years, an early start can be made in the FY2025 National Budget with emphasis on items iii), iv), v) and vi). Items iii), iv) and v) can have substantial positive revenue effects by eliminating leakages resulting from the present system of one-on-one dealings between the taxpayer and tax collector and the incidence of negotiated settlements. These reforms will also encourage greater tax compliance by eliminating the prospects of harassment resulting from the complexities of the income, expenditure and wealth reconciliation requirement and the personalised tax collection and audit system. Implementation of the 2012 VAT Law can also have substantial revenue boosting effects by reducing exemptions and improving the efficiency of the VAT system. In Table 1, the implementation of these reforms is conservatively estimated to yield additional tax revenue of 0.9% of GDP in FY2025.

Generating higher revenues through SOE reforms: The government has invested heavily in SOEs. Most SOEs suffer from operating losses. Only a few enterprises make profits, mostly involving Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC), Telecoms Regulatory Authority and the Chittagong Sea Port. As a result, as against a book value of total non-financial SOE assets of 17% of GDP in FY2021, profits were a mere 0.6% of GDP. A 10-12% financial rate of return should yield profits equivalent to 1.8–2% of GDP. Research done by the PRI shows that a combination of corporate governance and pricing problems constrain the financial performance of SOEs. The research has also identified specific policy reforms to turn-around this performance. Corporate governance reforms essentially involve giving autonomy to SOEs in the selection of management, staffing, production and investment decisions, while keeping an arm’s length relationship with the government as owners and also facing a hard budget constraint. This is the only way that SOE management can be held accountable for performance. Pricing reform entails setting market prices for SOEs operating in a competitive environment, while establishing autonomous regulatory bodies to set prices for public utilities.

While implementation of the corporate governance reform will take time, pricing reforms can be easily done and will immediately boost non-tax revenues by increasing the profitability of SOEs. In Table 1, it is conservatively assumed that the Treasury can raise an additional surplus of 0.3% of GDP from SOEs in FY2025.

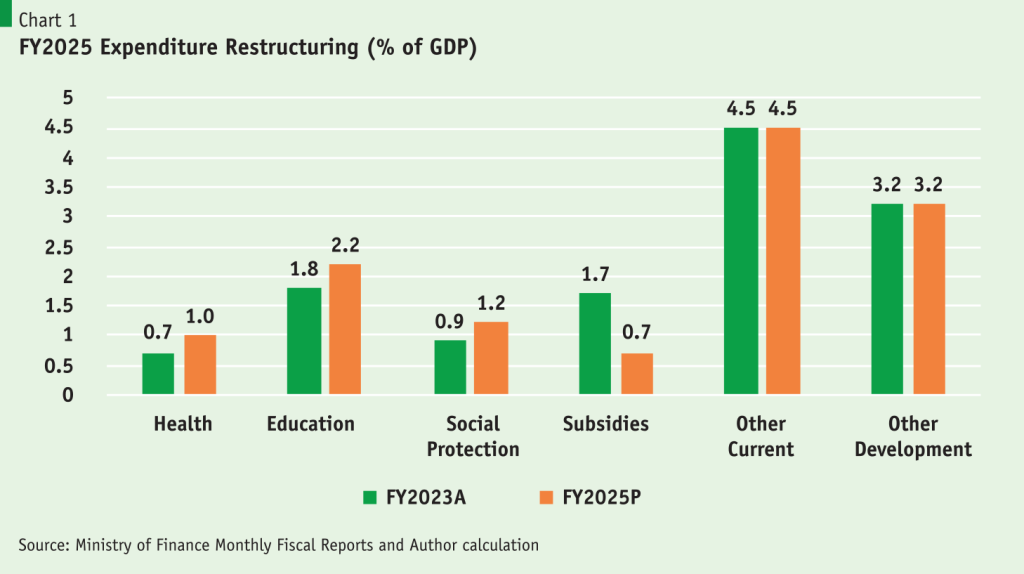

Reforming expenditures to minimise subsidies and increase higher priority spending: This is an easy win. Subsidy on fossil fuel is contradictory to the government’s stated intention to reduce its carbon imprint. So, eliminating this subsidy will help reduce carbon emission. It will also save considerable budgetary resources. By freeing up the exchange rate the government can also eliminate subsidies on exports and remittances. Some agriculture input subsidies on fertiliser, seeds and water may be necessary, but these can be contained to a modest level. The shape of the restructured expenditure pattern is illustrated in Chart 1. Overall, it should be possible to reduce subsidy spending from a high of 1.7% of GDP in FY2023 to 0.7% of GDP in FY2025. The savings of 1% of GDP can be redeployed to spending on health, education and social protection. Additionally, of the 1.2% of GDP mobilised through higher revenues, 1% of GDP can be used to reduce the budget deficit while some 0.2% of GDP can be used to further boost spending on health, education and social protection.

Chart 1 illustrates the power of such expenditure restructuring in a constrained revenue and spending environment. In addition to significantly lowering the budget deficit to reduce aggregate demand, expenditure restructuring reallocates public spending from subsidies to human development and social protection. This restructuring will be much more supportive of the poor than untargeted general-purpose subsidies that also hurt the climate change agenda. The graph also powerfully illustrates how deficit reduction can be reconciled with the poverty reduction agenda.

Non-inflationary financing of budget deficit: Treasury borrowings from BB to finance budget deficit has been a major source of inflationary pressure. By eliminating such borrowing, the budget can make a positive contribution to reducing inflation. Instead, deficit financing can rely on additional foreign funding in the form of budget support loans, use of national savings certificates and selling T-bills to the general public.