Role of Tax Policy in Inequality Abatement

By

1. Introduction and Context

A key feature of the currently pursued economic growth model is that it is often not associated with reducing inequalities in income or consumption. Accordingly, after a pause, the discourse on inequality is back. Sustained economic growth in the last three decades has been effective in reducing poverty – in spite of rising inequalities in income or consumption. The inability of economic growth to reduce inequality has motivated many countries to emphasise policies to support inclusive growth.

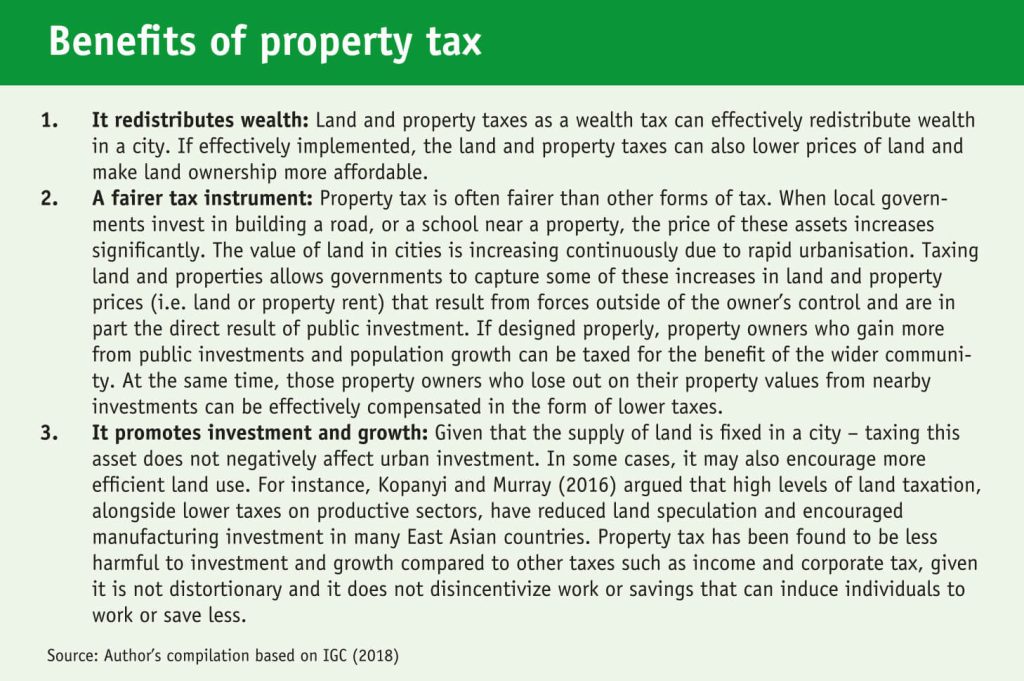

If implemented appropriately, fiscal policy which is composed of a tax and expenditure system can be seen as an effective policy instrument to ensure equity. However, the progressivity of a tax system can be nullified by a regressive expenditure system and vice versa. Thus, the equity aspect of the tax system can be best understood in the context of the entire fiscal system. Fiscal policies are heterogeneous across different regions of the world as delineated by indicators such as tax efforts; tax composition; and expenditure patterns. Tax efforts (i.e. tax to GDP ratio) in developing countries are significantly lower than in the developed countries. Low tax efforts limit the fiscal space and the spending capacity of a country. Moreover, a major portion of the tax revenue in developing countries has been collected through the indirect tax system – which is regressive and it imposes disproportionate burden on the less well-off groups. Diversity of the tax system is also underdeveloped in developing countries given the weaker role of wealth and inheritance tax – two types of direct taxes known to reducing income inequality. Taxes on land and property, known as property tax, are also at nascent stage in many developing countries. If administered properly, land and property taxes as a wealth tax can also effectively redistribute wealth within society. Inability to tax the informal sector and widespread tax evasion in collusion with corrupt tax administration underpins this low tax effort and increases our dependence on public debt – denting the pathways to ensure equity for the future generation.

Against these developments, the article summarises key findings of a literature review by focusing on the implications of the tax types on inequality in particular and on the economy in general. Since Bangladesh has the dual problem of high (underestimated due to lack of data of the richer segment of the society) inequality and low tax efforts with low share of direct taxes in tax revenue, some of the findings may have relevance for the tax reforms in Bangladesh.

2. Review of Literature on Approaches to Equity via Tax System

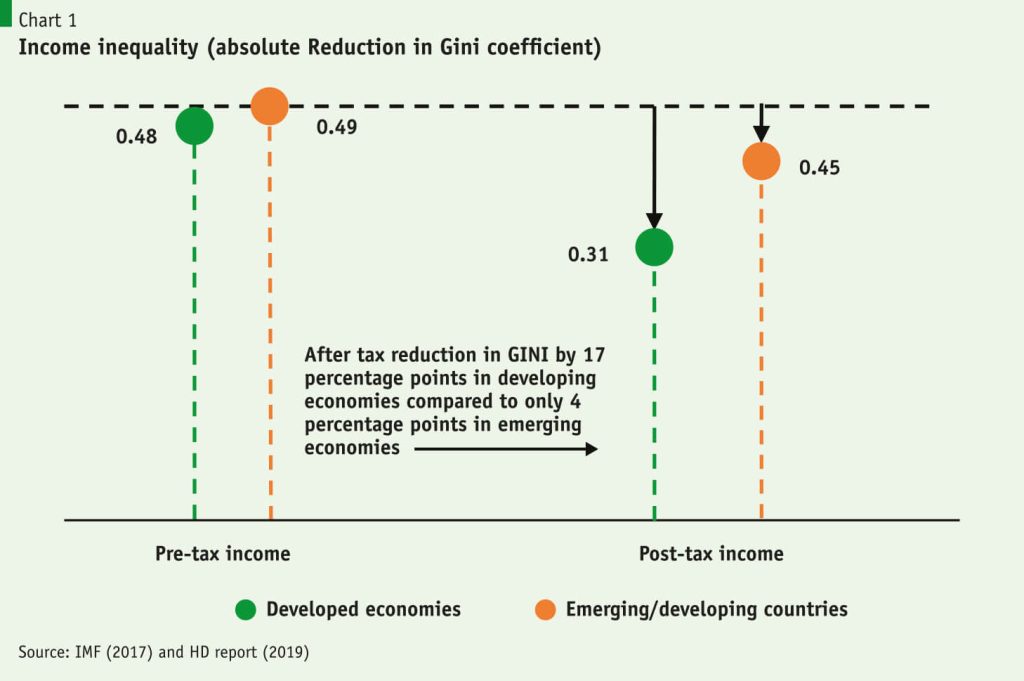

In the past decade, the commendable progress in fight against poverty has reduced income disparities across the world. Income and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) have seen remarkable growth in many emerging economies. However, the decadal healthy growth has not supported the distribution of wealth and income in many developing countries, which experienced a widening income gap between the rich and the poor. The growing inequality indices (i.e. GINI and the Palma Ratio for instance), constructed using Household Budget Surveys, clearly reveals the biased impact of economic growth on the richer segment of the society. This highlights the need to understand the causes of inequality and the necessity to build suitable policies to reduce the gap. However, it is also highlighted that given the data limitations and exclusion of high-income groups in developing countries, it is highly likely that the actual inequality picture is worse than portrayed. Nora Lustig (2018), provides an excellent synthesis of the factors that give rise to the ‘missing rich’ problem in household surveys – especially in developing countries. It is recognized in literature that tax policy in this respect can play a major role in making the post-tax income distribution less unequal (Carter, 2012).

Is Progressive Income Tax the Answer?

According to various OECD studies, progressive taxation of income is one of the main ways’ governments can redistribute income. However, the effects of taxation on income distribution needs to be seen in the context of the trade-offs between growth and equity, and this means looking at the overall effects of any reform on the fiscal regime as a whole, and not just at whether individual taxes are progressive or regressive (Carter, 2012). This is because lower inequality is not only guaranteed by proper tax collection but also on redistribution in the form of benefits to those with lower incomes. In this respect, governments’ intervention to reduce inequality and poverty should be brought through employing both the tax and benefits systems which would take proportionately more tax from those on higher levels of income, and redistribute benefits to those on lower incomes. On average in the OECD, around three quarters of the reduction in inequality were due to such transfers; personal income taxes and social security contributions (SSC) account for the remaining quarter (Causa, 2019).

…governments’ intervention to reduce inequality and poverty should be brought through employing both the tax and benefits systems which would take proportionately more tax from those on higher levels of income, and redistribute benefits to those on lower incomes.

Household budget surveys further suggest that OECD-wide taxes and cash transfers reduced the market income dispersion – as measured by the concentration coefficient – by about 25% and relative poverty by about 55% in the late 2000s (Pisu, 2012). The data clearly portrays a positive link between the redistributive impact of taxes and transfers and the level of market income inequality (Pisu, 2012).

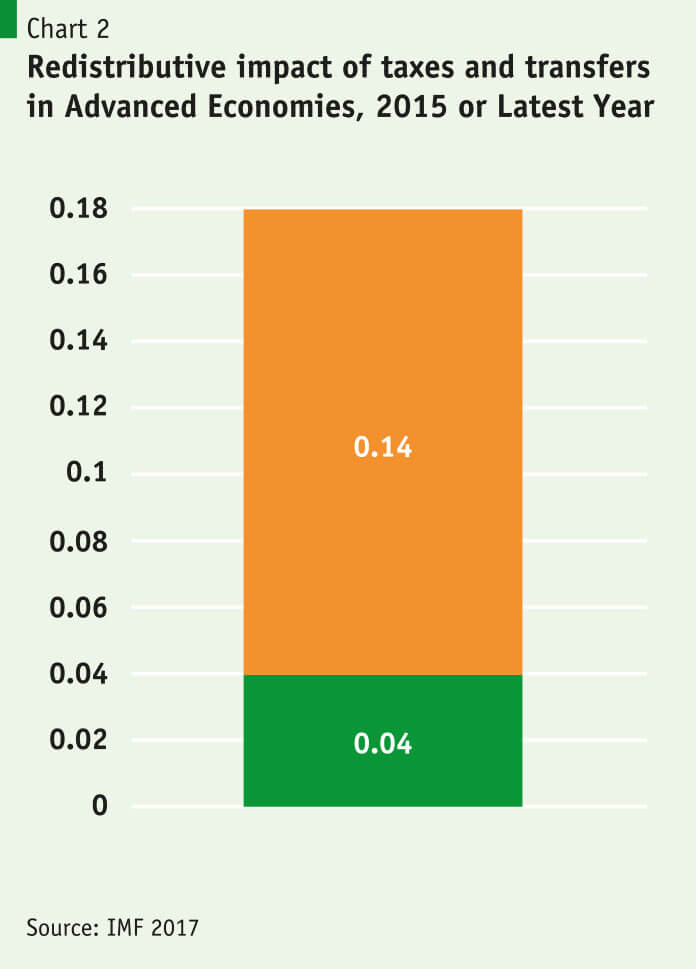

IMF (2017) envisaged that fiscal policy can help reduce income inequality through various channels. First, progressive direct taxes and transfers can reduce disposable income inequality (that is, inequality of income after taxes and transfers) so that it is less than market income inequality (that is, inequality of income before taxes and transfers). Second, it further qualifies that the extent of fiscal redistribution will depend on both the magnitude of taxes and transfers and their progressivity (Arestis, 2018). Adjacent chart captures the impact of tax and transfers on the absolute reduction in GINI of OECD countries. The Impact of these policies on GINI reduction is 0.18 of which transfer accounts for 0.14 per cent.

In light of employing a proper tax mix to discourage inequality, horizontal and vertical equity play important roles. Policy reforms towards inequality and poverty are often influenced by the desire to achieve both horizontal and vertical equity Horizontal equity demands a guideline for tax and benefits policy in which individuals in the same financial circumstances have the same fundamental ability to pay taxes, and, therefore, should be taxed at the same rate. The principle of vertical equity on the other hand is concerned with redistributing income within society. It demands higher tax rate for people with higher incomes thus entailing a proportional or progressive tax policy.

However, even with a progressive tax system in place, many countries do not witness significant improvement in income distribution or narrowing inequality. The loopholes existing in the system allow certain groups of companies’/individuals preferential tax rates, tax exemptions, high tax-free thresholds and scopes for evasion. This compromises the objective of achieving horizontal equity. Proper tax realisation therefore still remains a major concern for many economies where simply raising marginal personal income tax will not reduce inequality.

Brazil for instance has remained a very unequal country despite having an overall tax burden similar to the OECD average (above one third of GDP), and its tax system as a whole, i.e., taking into account both direct and indirect taxes, actually increased inequality. This was due to a high reliance on regressive indirect taxes; low progressivity of the personal income tax; and a cap on social security contributions (Brief, 2015).

Can Progressive Consumption Tax Address Inequality?

Some also argue switching from income tax to a progressive consumption tax can address growing wealth inequality. On the grounds of simplicity and efficiency, a consumption-based tax system can definitely raise revenue. Kenneth Rogoff carefully highlights the debate on this issue in an article on World Economic Forum titled ‘Could a progressive consumption tax reduce wealth inequality?’. It analyses how an ultra-millionaire tax can raise revenue collection to a significant level. Contrary to this theory, a better path has been argued to be the implementation of a broad range of more conventional fixes, including an increase in the corporate-tax rate and eliminating ultra-wealthy families’ ability to avoid capital gain taxes through bequests (Rogoff, 2019).

In her paper on Consumption Taxes and Redistribution, Portuguese macroeconomist Isabel Correia analysed the effect on welfare equity of replacing labour-and-capital-income taxes with flat tax on consumption, complemented by a large lump-sum transfer to every household. She shows that the reform results in both higher efficiency and equality, implying that the households at the lower end of the welfare distribution are made better off (Correia, 2010). Correia’s analysis focuses on the long run, but with a transition suitably designed to protect small family businesses, it should be possible to ensure short-run gains as well (Rogoff, 2019).

Carter (2012), argued that the absence of a proper transfer structure, consumption tax can prove to be harmful in low-income countries. According to him, ‘raising indirect taxes, for instance, is often regressive where these taxes fall on the consumption of goods and services that make up a larger share of the budgets of poorer than richer households. However, even if a regressive indirect tax system is in place, the effects of it can be counterbalanced by other tax and benefit changes (Carter, 2012)’. Income-related benefits, for example, are a much more efficient way of increasing the disposable income of poorer households than reduced rates of consumption tax for the poor (Carter, 2012).

What Role Can the Property Tax Play in Reducing Inequality?

Given the tendency of the wealthy to escape tax brackets, property tax can prove to be highly effective in taxing the wealthy. Lack of an adequate tax base on wealth and property amplifies income inequality. High income holders are investing in land and properties and escaping the periphery of the income tax band. By promoting idle resources, governments of many emerging economies deprive themselves from the avenue of significant revenue generation. While countries do not necessarily need to tax property at higher statutory rates than personal income tax, there are strong arguments for broadening the base of property taxation to raise both efficiency and equity (OECD, 2018). Property taxes are economically efficient, easily linked to service provision, and should be relatively easy to enforce owing to the immovability of property. However, it has to be uniformly enforced, and progressive in nature to ensure a reducing gap in income and wealth.

Is There an Agenda for Equitable Taxation?

A paper by Wilson Prichard on Agenda for Equitable Taxation has carefully identified a few key elements of a more equitable tax system or agenda. The paper primarily focuses on refining and developing the already existing agreements and policies related to taxation. The brief presents the following tax reforms as key elements (some of which have been discussed above) that may help reduce inequity:

- Stronger and broader personal income taxes

- Improved property taxation, emphasising simplicity

- Transparency around tax exemptions

- Improved taxation of multinational corporations (MNCs)

- Reducing opportunities and incentives for informal taxation

- Pairing consumption taxes with simple exemptions for essential goods

- Encourage civic engagement and reciprocity

- Reasonable efforts to balance potentially poverty-increasing taxes with new transfers.

However, it is important to understand that switching or reforming tax systems would require a potentially complex transition. The distortionary effect of progressive taxation cannot be ignored. It can disincentivize work – culminating in reduced investment, entrepreneurship and labour supply, and also provide strong incentives for individuals to reduce their tax liability (OECD, 2018). This means that the inequality-reducing effects of taxes and transfers will critically depend on the interplay between the size (i.e. transfers received/taxes paid relative to household income), the tax mix and the progressivity of the system (targeting in the case of transfers).

Moreover, it may also entail an agreement at the global level and international coordination enforcing the agreements. Otherwise, it may open up competition to shift resources from country to country in search for lowest tax incentives, which requires multilateral cooperation.

3. Concluding Observations

This article tries to synthesise the role of tax policy in abating inequality in income and consumption. Careful review suggests that a country may resort to various types of taxes to raise revenue with a focus on improving inequality or at least arresting the worsening of it. In a country like Bangladesh where tax effort is extremely low, and inequality is high the reform agenda should cover two components of the tax policy – tax system and tax administration. Reforms in the tax system focus on direct tax and their progressivity (i.e. revenue and equity consideration); less distorted consumption such as consumption VAT (i.e. revenue consideration); and property tax (i.e. revenue and equity consideration). It is also important to recognise the crucial role of an efficient tax administration in pursuit of both efficiency and equity. The reform may focus on following aspects:

- Enhancing the share of direct tax in total tax mobilisation;

- Introducing or expanding property tax;

- Introducing or expanding a broad-based consumption tax (value added tax);

- Lessening tax evasion and the shadow economy; and

- Improving efficiency and transparency of the tax administration.

…the reform agenda should cover two components of the tax policy – tax system and tax administration. Reforms in the tax system focus on direct tax and their progressivity

References

Nora Lustig (2018), provides an excellent synthesis of the factors that give rise to the “missing rich” problem in household surveys – especially in developing countries. Citing the works of Alvaredo and Londoño-Velez, 2013; Alvaredo et al., 2015 and Belfield et al., 2015), she stated that ‘the missing rich problem may explain as well why there are striking discrepancies in inequality levels and trends, depending on the source of the data (e.g., surveys vs. tax records).’

Carter, Alan. How Tax Can Reduce Inequality. OECD Observer (2012)

Causa Orsetta and Mikkel Hermansen. Income Redistribution Through Taxes and Transfers Across OECD Countries. OECD Working Paper (2019)

Joumard, Isabelle, Mauro Pisu and Debbie Bloch. Tackling income inequality: The role of taxes and transfers. OECD Journal: Economic Studies (2012)

Arestis, Philip and Sawyer, Malcolm Inequality: Trends, Causes, Consequences, Relevant Policies, 2018

Brazil Policy Brief. Improving Policies to Reduce Inequality and Poverty. OECD Better Policies Series (Nov 2015)

Rogoff, Kenneth. Could a progressive consumption tax reduce wealth inequality? World Economic Forum (Sept 2019)

Correia, Isabel, Consumption Taxes and Redistribution, American Economic Review, 2010

OECD, Tax Policies for Inclusive Growth in a Changing World, 2018

Prichard, Wilson What Might an Agenda for Equitable Taxation Look Like, ICTD