The costs of industrial protection: Who pays?

By

Ghosts of protection

Protection to domestic industries has been an integral part of Bangladesh economic policy since independence. This was one policy we inherited from Pakistan times without much thinking, as if it was received wisdom for all developing economies aspiring to become industrialised. In the 1970s, there emerged an alternative path to industrialisation and growth: export-oriented industrialisation. The success of the East Asian economies – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore – showed the way. China is an extraordinary example, having achieved double-digit gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates for a quarter of a century on the back of exports. Bangladesh finally moved to embrace the policy of export orientation and trade openness, although this has been gradual and intermittent over the past 30 years or so. A closer review of the state of industrial protection as it stands today reveals that the ghosts of protection remain alive and kicking, imposing costs on the economy. This is despite the fact that Bangladesh has achieved enormous success in export-oriented industrialisation and growth.

Since the switch to trade openness in the early 1990s, exports have averaged double-digit growth. The dynamic export-oriented readymade garment (RMG) industry is now a global showcase of entrepreneurship and competitiveness, a robust validation of trade theory on comparative advantage driven by specialisation based on resource endowment – in this case cheap labour. But this validation of trade theory did not come easy in an economy where high tariff protection persists stubbornly to this day. This is another validation of the political economy of trade protection, whose basic premise is that trade protection, once started, takes a life of its own, giving rise to vested interests that wield sufficient influence on policy-making to prevent dismantling of the protection regime. This means that, if there are social and economic costs associated with persistent protection, these are being borne by some groups, with full knowledge of these costs or without. It is the premise of this brief analysis that the burden of protection costs falls unevenly on consumers in Bangladesh, and yet they are increasingly becoming the growth drivers of this economy as it transitions from being a purely investment-driven economy towards being a consumption-driven economy. But are they being treated fairly in the policy space?

…the burden of protection costs falls unevenly on consumers in Bangladesh, and yet they are increasingly becoming the growth drivers of this economy as it transitions from being a purely investment-driven economy towards being a consumption-driven economy.

Bangladesh is on track to graduate out of least developed country status by 2024. The latest data coming out of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics shows the economy’s GDP at $270 billion, with a per capita income of over $1,700. The poverty headcount is down to 24%, and the middle class is on the rise. This comes as no surprise: glimpses of the country’s emerging income status can be foreseen in the everyday sights of buzzing restaurants, crowded shopping malls and burgeoning retail stores sprawling across the country. Yet the reality is that a close inspection of Bangladesh’s tariff structure gives no indication that tariff trends are moving in the direction reflective of a dynamically growing economy moving up the income scale to middle-income status.

The surging middle class

Bangladesh’s middle class is surging in size and spending power. In a recent roundtable held in Dhaka, the global market research firm Nielson shed some perspective on this phenomenon. Its findings highlighted the rapid expansion of the middle class in Bangladesh – fuelled by rising disposable incomes – and their propensity to spend on new and wide-ranging products and services. According to Nielson’s estimates, the number of retail stores in the country has grown by 8.6% year-on-year to 1.64 million in 2015. This momentum is continuing.

These findings substantiate previous research on this development, particularly a Boston Consultancy Group (BCG) report (2015) entitled, ‘Bangladesh: The surging consumer market nobody saw coming’. This report focuses particularly on the middle and affluent class (MAC) in Bangladesh, defined as consumers earning more than $401 (approximately Tk. 34,000) a month, or above $5,000 annually. This segment of consumers, estimated at around 12 million strong, provides insights into the consumption trends of goods and services that go beyond basic necessities and into the realm of convenience and luxury. Examples include air conditioners, flat-screen TVs and imported cosmetics. What is evident from the report is the rapid expansion of the consumer class, and their eagerness to spend their cash surplus on quality brands, goods and services – regardless of origins. If you add to this the larger group of lower-middle-class (LMC) consumers who buy a whole range of import substitute consumer products, this will add another 25 million to the MAC population. BCG projects the size of Bangladesh’s MAC population to rise to 34 million by 2025, when our GDP will have crossed $500 billion. The MAC plus LMC consumer market could reach $100 billion – an attractive market indeed in terms of size and spending power. The question is, what prices do Bangladeshi middle class consumers pay as they grow in number?

Yet the report by BCG is also quick to point out that the Bangladeshi MAC population accounts for only 7% of the country’s population – meagre by Asian standards. In comparison, the number stands at 21% for Vietnam, 38% for Indonesia and 59% for Thailand. Recognising that Bangladeshi consumers pay around 70–100% above world prices for consumer products – either imported or produced locally – this does not seem all too surprising.

Bangladeshi consumers pay high tariff-induced prices

While liberalisation of the import regime since the 1990s has given consumers more choice, they still continue to pay prices for consumer goods that are well above international prices – and it seems they have accepted this almost without complaint – until now. The Consumer Association of Bangladesh (CAB) is now voicing concern that consumers are being left out of budget consultations and discussions on tariff-setting, even though they are the ones who ultimately bear the burden of the tariffs.

Even on a global scale, Bangladeshi consumers incur the highest average rate of tariffs on imports, especially compared with their Association of South-East Asian (ASEAN) neighbours, all of whom face substantially lower average rates…

Even on a global scale, Bangladeshi consumers incur the highest average rate of tariffs on imports, especially compared with their Association of South-East Asian (ASEAN) neighbours, all of whom face substantially lower average rates, as shown in Table 1. Since tariff rates on consumer goods are typically higher than average rates, it might be astonishing to many but the fact remains that Bangladeshi consumers pay some of the highest prices for consumer goods in Asia, if not the world. It becomes starkly obvious, then, why the Bangladeshi MAC population today comprises such a small portion of the population compared with that in its neighbours and comparators.

Tariffs serve the dual purpose of generating revenue and protecting domestic manufacturing activities. Though a strategic shift has been taking place as the National Board of Revenue (NBR) moves away from its reliance on trade taxes to increase its reliance on domestic taxes such as Value Added Tax (VAT) and income taxes, trade taxes (customs revenue) still remain a significant component of NBR revenues (about 30%). Scaling down tariff protection is often viewed as giving up revenue, which accentuates the resistance to tariff reduction. But this is counterintuitive. If tariff protection is effective, it restricts imports and revenue is constrained. Barring the high tariffs and para-tariffs on automobiles, alcoholic beverages, cigarettes and firearms (meant for revenue mobilisation or discouraging consumption), other high tariffs on consumer goods imports have an inherent protection objective. To the extent that protection is effective in restricting competing imports, revenue mobilisation becomes a sideshow (especially in the application of Supplementary Duty). More revenue could be raised by removing or scaling down Supplementary Duty on consumer goods that typically have high income and price elasticities.

Measuring the costs of protection

Economists measure the cost of protection in terms of static efficiency, growth rates and firm- or industry-level productivity effects. Economist Arvind Panagariya (2002) lucidly summarised the findings of many empirical studies of protection costs, concluding that high protection imposed high costs on the economy, which could range from 2% to as high as 10% of GDP. Bhagwati (1982) added the political economy dimension to this discourse in putting the lobbying costs (which he termed as ‘directly unproductive profit-seeking’ (DUP) activities) on the table. Bangladesh’s tariff protection structure presents a unique case, where much of the protection is accorded to producers of import substitute consumer goods (with a minimum of protection going to the production of intermediate or capital goods). This makes it possible to implement a unique but simple approach to measuring the costs of protection to consumers – measuring the divergence between the international price and the tariff-induced domestic price of protected consumer goods. The focus of this analysis being on consumers, we avoid the complexities arising from the theoretical framework of deadweight losses endured by society (when gains to producers from price hikes and to government from revenue fall short of losses to consumers).

A tariff raises the domestic price of the product over the international price by at least the amount of the tariff. As such, it is in essence a tax on the consumer and a subsidy to the producer, in the sense that, without it, the producer would have to sell at the international price, which is lower. At the end of the day, it is consumers who bear the burden of these tax instruments as producers pass on the tax burden to consumers in the form of higher tariff-induced prices including mark-up. Moreover, the higher tariff-ridden prices contribute to restraining imports and limiting the consumers’ choice. PRI research has monitored trends in nominal tariffs and landed cost of imports for over 25 years in order to be able to measure the extra cost to consumers as a consequence of protective tariffs on consumer goods.

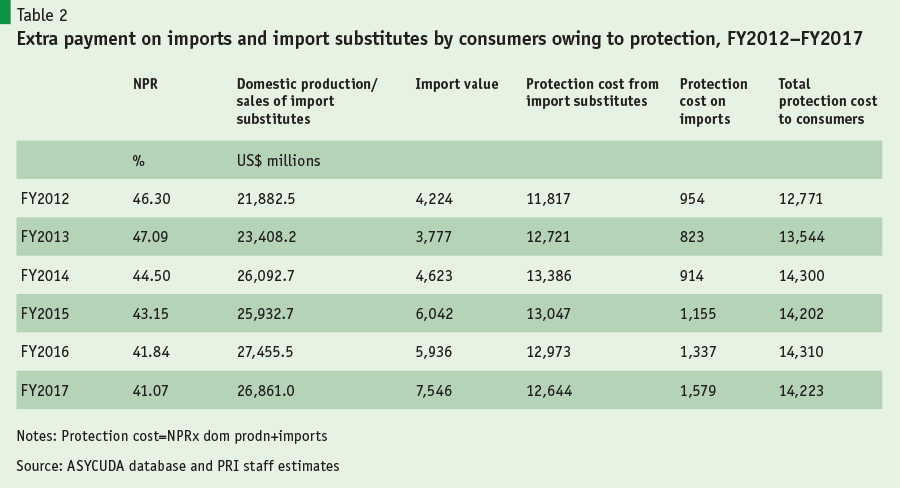

In theoretical terms, a tariff leads to a gain in the producer surplus but a loss in consumer surplus that can be broken down into two effects: the revenue effect and the redistributive effect. The revenue effect refers to the transfer of the consumer surplus to government in the form of higher government revenue, whereas the redistributive effect refers to the transfer in consumer surplus to producers. Consumers pay not just a higher price for the imports but also an extra cost in the form of higher prices on domestically produced import substitutes, as producers potentially raise prices up to the tariff-induced price. Estimations of the extra cost borne by consumers owing to protective tariffs can then be computed by adding up the protection-induced price effect (the nominal protection rate, NPR) – extra cost – on the sum of imports and domestically produced import substitutes. These costs are then propounded as a proportion of GDP. Table 2 highlights these computations for several years from FY2012.

This estimate of the protection cost is based on the importation of consumer goods and domestic production and sale of import substitute consumer goods only. During the five-year period, FY2013–2017, the total protection cost to consumers works out to a substantial amount of $70.6 billion. For FY2017, the protection cost to consumers works out to $14.2 billion, or 5.7% of FY2017 GDP, and 31% of manufacturing value added. This is in essence the extra cost consumers pay over international prices – a veritable transfer of resources from the pocket of consumers to that of producers. Although the average NPR for all consumer goods works out to 44% for the period in view, the top protected ones have an NPR ranging from 53% for soap and toiletries to 156% for air-coolers and non-alcoholic beverages. Taking total tariffs into account (including VAT paid by consumers), on average consumers paid 70% above international prices for buying consumer goods in the domestic market.

In pursuing this issue further, it is useful to look deeper into the NPR. The NPR provides the total proportional difference between domestic and international prices of a good, taking into account import tariffs and para-tariffs (trade taxes other than customs duty). Domestic prices could also be subject to other market distortions such as licensing, prohibitions and price controls. Therefore, in principle, analysing the NPR provides an estimate of the total price-raising effects of tariffs and other trade restrictions. In the absence of any robust estimate of the distortive effect of other restrictions, the NPR is a reasonably good estimate of the price-raising effect of tariffs and para-tariffs (i.e. the protective effect of customs duty and other trade taxes). In Bangladesh, research shows that the majority of all domestically produced manufactured products are subject to the highest NPR rate. At present, the consumer products with the highest rate of NPR include air conditioners (156%), plastic tableware and kitchenware (113.44%), non-leather footwear (113.44%) and sanitary wares (104.80%) – products that have been integral in fuelling the rapid expansion of the brand-savvy MAC population. As such, despite the resilience of the Bangladeshi consumer class, the financial burden of tariffs continues to act as a major constraint to its growth.

Consumers suffer collective action failures

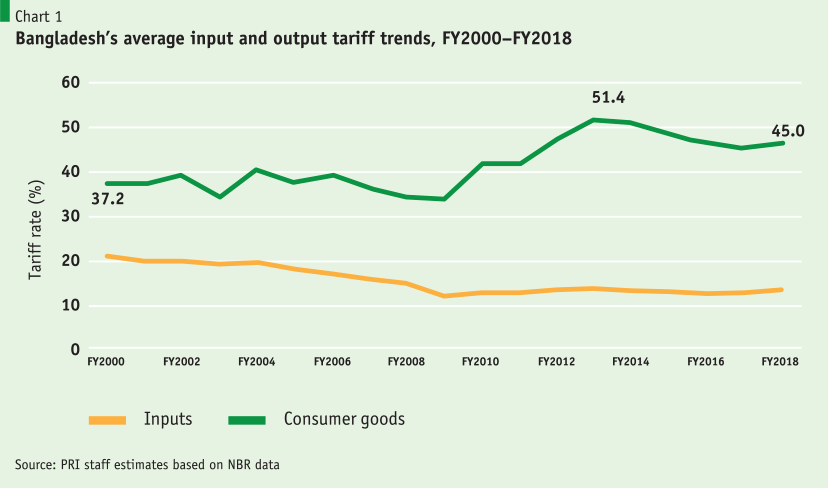

Evidently, when it comes to tariffs, the consumer seems to have no voice. Amid a plethora of stakeholder consultations pre- and post-budget organised around the year, chamber representatives put forth various proposals for tariff adjustments, understandably, to raise their profitability, which can happen if output tariffs are raised or input tariffs are cut. In the past five years, input tariffs have been cut such that they now average about 13% while output tariffs average 46% – all benefiting producers. This divergence between input and output tariffs is shown in Chart 1. Producer groups, of which there are many, lobby hard to get input tariffs (on intermediate, capital and raw materials) reduced and output tariffs (on consumer goods) increased as much as possible. Their goal basically is to get higher tariffs on the outputs they produce and lower tariffs on the inputs they source from imports or domestic suppliers. To the extent that producers get their way – and it seems they do – the outcome is skewed in favour of producer interests and against consumer interests, as consumers end up paying prices that are significantly above international prices. This is essentially a protection tax on consumers. But nobody, not even CAB, has raised the issue of how long consumers should continue to be taxed to protect producers. This situation is quite unique to Bangladesh and not something that is much talked about in economic literature.

Why do producers consistently get their way at the expense of consumers? Economist Mancur Olson (1971) offered an answer in his Logic of collective action. According to Olson’s theory, smaller groups are generally easier to organise, and more effective in lobbying their case than larger groups, which have difficulty in organise themselves to press their case, however strong it may be. And, typically, the smaller the group, the quicker it is able to organise, and the more vociferous it becomes in pushing its demands. As such, it becomes easy to see why consumers – spread all over the country and comprising children and adults, students and professionals and a host of other categories of individuals, simply cannot organise themselves to press for their legitimate demands for lower prices and a greater choice of goods, as easily as, say, the small yet powerful producer groups.

Amid the ever-growing demand for consumption, rationalising the protection regime has become a national imperative, to spur domestic spending to fuel growth.

Rationalising protection as a national imperative

The strategy of import substitute protection for industrialisation comes at a high price in Bangladesh, paid for by consumers who end up bearing the brunt of the protection tax. This could make sense only if it were a time-bound initiative. But theory and practice tell us that this is not how protection works. Once started, it takes a life of its own. Besides, import substitution has not given us jobs and growth. Export orientation has. RMG success is not a story of import substitution transiting into exports; it started off as an export industry. Not only is the economy stuck in the quagmire of high protection, but also this policy is characterised by an anti-export bias, which is preventing numerous non-RMG exports (some 1,400 products in FY2017) from becoming significant export items, thus hampering the product diversification of exports. Amid the ever-growing demand for consumption, rationalising the protection regime has become a national imperative, to spur domestic spending to fuel growth. It is time for CAB to become proactive on the issue of protection costs, thus going beyond those of ensuring unadulterated foodstuff or proper product labelling.

References

BCG (2015)’“Bangladesh: The surging consumer market nobody saw coming’. Boston: BCG.

Bhagwati, J. (2982) ‘Directly unproductive profit-seeking (DUP) activities’. Journal of Political Economy 90(5): 988–1002.

Olson, M. (1971) The logic of collective action. Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Panagariya, A. (2002) ‘Alternative approaches to measuring the cost of protection’. Mimeo. College Park, MD: Center for International Economics, University of Maryland.