Looking for Trade Policy directions in the Forthcoming Budget

By

The FY2025 Budget, coming in the first week of June, will give us economists an idea of whether the new Government means business. In the past couple of years, the economy has confronted challenges on multiple fronts, particularly with respect to the country’s external balances. Thankfully, engagement with an IMF program creates the scope for managing the external shocks and internal instability, characterised by high inflation, with sound technical analysis and supporting policy programmes.

Among the critical economic challenges that have emerged as the economy faces impending graduation out of LDC status in 2026 and consequent phase out of International Support Measures (ISM) together with preference erosion in market access, are i) the impact of trade taxes (tariffs and para-tariffs) on export performance and its diversification and ii) the persistence of high inflation for over two years. Following the presentation of the Annual Budget, the media is usually awash with reporting on the fiscal dimensions of the Budget and its potential impacts. What appears to catch least attention is the trade policy regime emanating from it. Even monetary policy directions can be gleaned from the budgeted fiscal operations – e.g. size of the fiscal deficit and its mode of financing.

The Government budget is not all about revenue mobilisation and allocation of public expenditure. A big chunk of it has to do with setting directions of trade policy, i.e. the domestic policy content of how exports will be stimulated and imports and import substitution will be managed through the imposition of tariffs and para-tariffs, impacting revenue and protection. Though the tri-annual Import Policy Order and Export Policy Order framed by the Ministry of Commerce (MoC) make up the regulatory regime for import-export transactions, the fact that quantitative restrictions on imports no longer exist for protection purposes, these Orders no longer constitute trade policy per se. In the last Trade Policy Review of Bangladesh, WTO noted that tariffs were the main instrument of trade policy in Bangladesh. If not the entire package of trade policy, tariffs do make up the bulk of Bangladesh’s trade regime. The Budget does articulate the structure and distribution of tariffs and other trade taxes. Economists have the task to sense the direction of trade policy from these stipulations.

In light of the balance of payments challenges, foreign exchange reserve depletion, and the exchange rate depreciation shock in the recent past, it is incumbent upon the forthcoming Budget to delineate the trade policy regime that will address, among other things, these challenges in a forthright manner, with standard and perhaps, innovative policies. In the export-import trade landscape, Bangladesh economy presents some unique features that call for unique policies.

This brief note will analyse, discuss and offer trade policy options for the budget to consider on two critical challenges facing the economy: i) the export diversification challenge, and ii) the challenge of stubbornly high inflation.

Addressing the Challenge of Export Diversification

Bangladesh’s economic landscape has undergone a significant shift, transitioning from a predominantly agrarian economy to one driven by manufacturing. Despite this, agriculture still plays a critical role, ensuring food security, contributing over 11% to GDP, and employing over 40% of the labour force.

With the manufacturing-GDP ratio surpassing the global average at 22%, Bangladesh’s growth has been fuelled by the remarkable rise of the ready-made garment (RMG) sector alongside other manufacturing industries. However, the non-RMG manufacturing sectors face challenges, particularly in export performance.

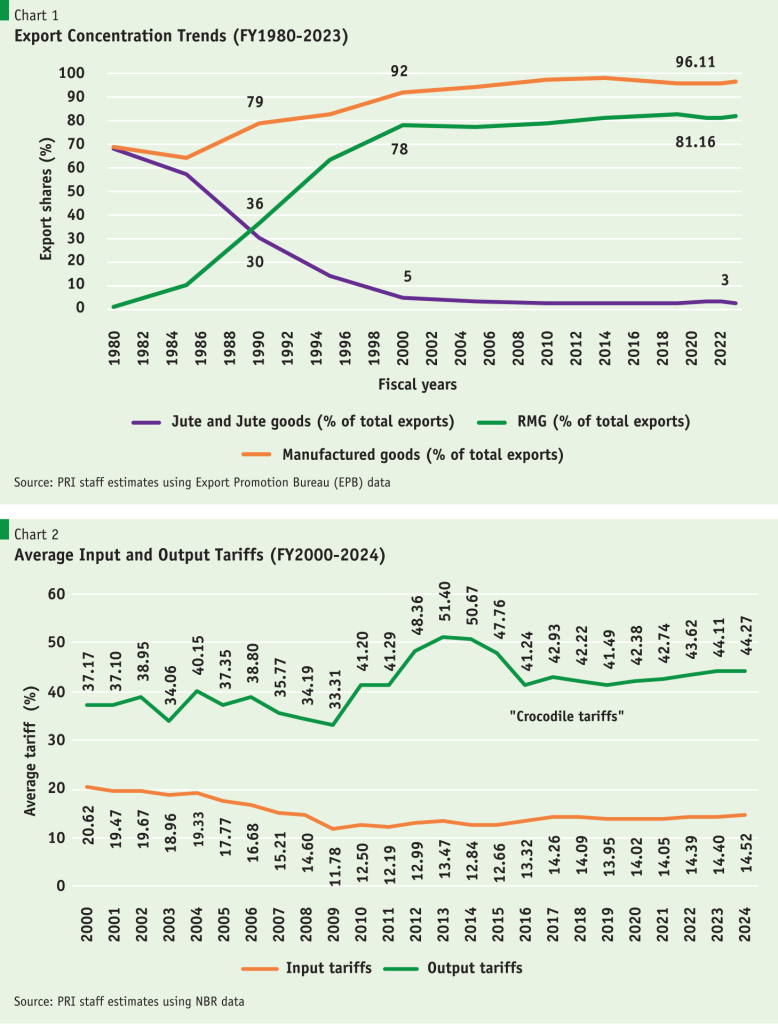

Over the past two decades, Bangladesh has seen impressive double-digit merchandise export growth, primarily driven by the RMG sector. Manufacturing goods constitute a remarkable 96% of the country’s exports, setting Bangladesh apart as an LDC with such a substantial share of manufactured exports. However, this heavy reliance on the RMG sector, which contributes 85% of export earnings, poses inherent risks, highlighting the urgent need to develop non-RMG exports to reduce concentration. (Chart 1)

One of the key drivers of the Bangladesh economy for the past decades has been the RMG industry, which has become an export behemoth for the economy. A trade policy innovation – duty-free imported inputs in a high tariff regime – ensured strong competitiveness in a labour-intensive export product, i.e. apparel. Although the success of the RMG sector is commendable, being a one-trick pony may not take Bangladesh very far. After graduating from LDC status in 2026, Bangladesh will lose a large chunk of the preferential benefits that it now gets in the western markets, especially in the EU (albeit with a 3-year lag). That could potentially undermine dynamism in RMG exports in the future. That calls for renewed focus on product and geographical diversification of exports.

After graduating from LDC status in 2026, Bangladesh will lose a large chunk of the preferential benefits that it now gets in the western markets, especially in the EU (albeit with a 3-year lag). That could potentially undermine dynamism in RMG exports in the future. That calls for renewed focus on product and geographical diversification of exports.

Chart 1 captures the trend of export concentration in RMG over time. The share of RMG exports has risen from 30% in 1990 to 78% in 2000 and is now about 84% in 2023. This trend toward concentration continues unabated. The share of RMG exports could hit 90% over the next five years if this trend is not reversed by higher growth in non-RMG exports.

Chart 2 shows how there is a persistent gap between average input and output tariffs over the years. This is a phenomenon called tariff escalation. The government keeps the tariffs on inputs lower than the tariffs on outputs/finished goods, so that the domestic producers get access to lower priced imports of raw materials. The higher output tariffs ensure that the competition from foreign consumer goods is lower and hence, the domestic producers retain an advantage in the domestic market. The trend of these input and output tariffs over the years create a sort of crocodile shape with a ‘hump’ of higher output tariffs during the 2009–2015 period. The snout of the crocodile is formed when the values of output tariffs plateau after 2016. The values of average input tariffs have remained fairly stable post-2009 ranging from 12–15%.

Bangladesh’s persistent history of protectionism in its tariff regime poses a significant challenge to exports in general and export diversification in particular. Despite sporadic attempts at rationalisation, the regime remains laden with WTO non-compliant para-tariffs, raising profitability of domestic sales, and hindering export diversification. Notably, the divergence between input and output tariffs fosters a high degree of anti-export bias, favouring domestic sales over exports. While the RMG sector benefits from a ‘free trade enclave’ due to the Special Bonded Warehouse system that ensures world-priced inputs, non-RMG exports face constraints due to trade policy dualism that generally denies duty-free imported inputs to them. No matter how much cash subsidy is offered to non-RMG exporters, such subsidies are no match to the high protective tariffs. As long as domestic import substitution remains more profitable than exports for non-RMG products, export diversification will remain elusive, to the point that the tariff regime becomes a binding constraint.

The forthcoming Budget must give new directions for trade and tariff policy that takes into account the constraint to export diversification posed by the prevailing tariff and protection structure. Hopefully, the kind of tariff rationalisation stipulated in the National Tariff Policy 2023 will be deftly articulated, in whole or in part, in the forthcoming Budget to address the problem.

Addressing the Challenge of Taming Stubbornly High Inflation

Inflation in Bangladesh was triggered by two simultaneous events in 2022: the supply chain disruption of the Russia-Ukraine war, which caused a spike in commodity prices (particularly for food, fuel, and fertiliser); and the sharp depreciation of the taka against the US dollar (which approximated to 30% as of September 2023). Though international commodity prices abated somewhat, the second-round effects of the two triggers are incurring their impacts. The 50% hike in fuel prices by the government in August 2022 did not help, either. General inflation is running at a tad below 10%, with food inflation at over 12%.

It is now clear that inflation in Bangladesh was induced primarily by cost-push factors. The impact of supply chain disruption and exchange rate depreciation was a supply shock that triggered inflation, which was reinforced by monetary expansion. The latter has now been reversed by Bangladesh Bank through the standard prescription of monetary contraction and interest rate hikes. Also, the tendency to finance the budget deficit by borrowing from BB (which is pure inflationary money creation) has been suspended since July 2023. A neutral fiscal policy is expected to limit the monetisation of the fiscal deficit to keep inflation at bay.

In Bangladesh’s context, the preceding standard prescription may only restrict demand but does not do anything to counter the supply shock emanating from import price hike and taka depreciation. Indeed, the severe import compression imposed on the economy by BB is likely to raise import costs (driven by scarcity), thus becoming an additional cost-push factor of inflation over time.

One particular trigger of inflation which needs to be seriously examined is the massive exchange rate depreciation. This has upset the cart of macroeconomic stability like no other event in my memory. Understanding the mechanism of exchange rate pass-through to inflation is critical for addressing the challenge at hand. The extent and periodicity of such pass-through depend on the economic environment that prevails, such as the degrees of i) exchange rate flexibility, ii) import penetration and share of imports in the domestic market, iii) competition or monopolistic structure in the domestic economy, iv) prevailing trade openness and v) public intervention in markets. As was evident, the speed of transmission or pass-through was almost contemporaneous and significant. The substantial triggering of inflation, prompted by the massive depreciation, sustains inflation as no compensating countermeasures are in sight or discussed.

Understanding the mechanism of exchange rate pass-through to inflation is critical for addressing the challenge at hand. The extent and periodicity of such pass-through depend on the economic environment that prevails…

So, how much of Bangladesh’s inflation is caused by the pass-through? From May 2022 to September 2023, the depreciation of the taka against the US dollar was approximately 30%. Given that Bangladesh is a small economy when it comes to its import share on the world market, it is a pure price taker facing a horizontal import supply curve. Domestic prices reflect import prices, converted to taka using the exchange rate plus any trade taxes. This results in a one-to-one rise in domestic prices corresponding to any rise in import prices, including any spike caused by exchange rate depreciation. However, the impact on overall price level (inflation) will depend on the degree of import penetration (share in GDP), import share in the domestic market, and share of imported inputs in domestic production. Using an applicable model, the IMF did a rigorous exercise to determine the precise degree of exchange rate pass-through and found that, of Bangladesh’s nearly 10% inflation, as much as 5% could be accounted for, directly or indirectly, by the exchange rate depreciation.

If that is the case, then what is the panacea? Is there any counter-measure that could neutralise, partly or wholly, the pass-through effect? The IMF’s ECF-EFF-RSF programme is largely focused on enhancing domestic resource mobilisation. As such, it is silent on the matter of prevailing high trade taxes which account for some 26% of the National Board of Revenue’s tax revenue. What is missing is any guidance regarding the changing composition of trade versus domestic taxes. The challenge of enhancing domestic resource mobilisation entails augmentation of direct domestic taxes, such as income and corporate taxes as well as the value added tax, while gradually reducing reliance on trade taxes. Furthermore, revenue augmentation has to be done by expanding the tax base rather than by raising any rates, as a matter of principle.

Trade taxes (that is, tariffs and para-tariffs), considered the most distortionary taxes in public finance literature, primarily have two objectives: i) to raise revenue; and ii) to offer protection to domestic industries. Raising tariff rates yields higher revenue up to a point (called the optimum rate) beyond which revenue yield declines (as imports fall) but protection continues to rise.

Bangladesh’s average tariffs, at 27.6% currently, is higher than the average of Low-income countries (9.79%), Lower middle-income countries (7.2%), High-income countries (2.02%), and the world average of 6%.

It is time we started rationalising our tariff structure, not just to make them comparable to those of our peers, but to make our exports more competitive and eliminate the anti-export bias of protection that has currently become a binding constraint for our national imperative of export diversification. The stubborn resistance to lowering or rationalising tariffs is based on the argument that revenue loss goes against the objective of enhancing revenue mobilisation, while domestic industries need protection to survive and prosper.

This is where our current tariff structure presents a uniquely Bangladeshi opportunity to counter the inflationary pass-through effect of depreciation, through an approach that can be described as ‘compensated depreciation.’ Rather than let the exchange rate pass-through have an unabated impact on inflation, it can be countered with a reduction in tariffs. In the Bangladesh import scenario, a depreciation of the exchange rate has the effect of raising tariffs across the board by exactly the percentage increase in the assessable value of imports. In this case, the 30 % depreciation of taka has resulted in a 30% rise in the value of imports. Even if the tariff rate remains unchanged, the higher import value now yields 30% more revenue from the same ad valorem tariff rate – equivalent to an increase in the tariff rate.

That is a bonus for NBR. Why? Without actually raising rates, revenue yields have risen due to an increase in import value post-depreciation.

Just as the exchange rate depreciation has a pass-through effect on domestic prices (in the form of inflation), so does any change in the tariff rate. As such, a negative pass-through trigger on inflation could be induced by a reduction in tariffs. If not the entire 30% depreciation, at least a partial remission in inflation could be induced by lowering some tariffs or para-tariffs—a case of compensated depreciation. This could be a ‘favourable disinflationary shock’ that could be delivered in the forthcoming national budget.

One low-hanging fruit is the 3% regulatory duty (RD) imposed on nearly half of all imports. Depending on how deep and how fast the government would like to see inflation tamed, the removal of RD could be associated with removing or setting various caps on supplementary duty (SD). These adjustments would incur negative pass-through triggers on inflation, just as the exchange rate depreciation triggered higher inflation in the first place.

To conclude, a downward shock to inflation (disinflation) could be brought about by a downward tariff adjustment. Any downward tariff adjustment would partly neutralise the price or inflationary impact of depreciation, swiftly and sharply. Some formulation of this radically and uniquely Bangladeshi approach to counter the inflationary impacts of depreciation—if the objective is to tame inflation swiftly and sharply— could be stipulated in the FY2025 Budget, without us having to wait for another 18–20 months for the orthodox monetary contraction to take effect.

The argument that tariffs cuts will cause loss of revenue is not valid in this case as all tariffs have increased by 30% due to taka depreciation. Furthermore, using exchange rate depreciation as a strategy for revenue mobilisation cannot be a valid tax effort. Simultaneously, the basic principle of effective protection tells us that the depreciation has raised effective protection by 30%, since both input and output tariffs have risen in tandem. Thus, neither the revenue nor the protection arguments hold water. Besides, import compression applied for the past year will soon have to be lifted as that policy is slowing down production activities and causing more pain than is necessary. Rising imports should yield more revenue for the NBR over the next few months.

Tariff remission of 5 to 10 to 15% (from existing rates) will have an immediate effect on domestic prices of imports as well as import substitutes and costs of production. This is one great opportunity to remove RDs as an emergency measure to control inflation. More downward adjustments in tariffs and para-tariffs could and should be done in the national budgets for 2025 and 2026, as part of the tariff rationalisation initiatives stipulated in the National Tariff Policy 2023. These measures are consistent with the need to get our overall tariff structure to be WTO-compliant as we approach 2026, the year of our graduation from LDC status.

The FY2025 Budget could give the right signals for addressing two of the critical challenges facing the Bangladesh economy: the challenge of export diversification and the challenge of stubbornly high inflation.