Can Bangladesh Develop Without Decentralising? Some Lessons from East Asia

By

Introduction

This article is the first in a series of three articles that tries to answer the title question drawing on lessons from East Asian countries. The answer is that it is highly unlikely that Bangladesh, a large country of 161 million people, can sustain its impressive development record with its current highly centralised government. Future development will become more knowledge intensive and institutionally demanding, needing strong governments, knowledge, and initiative at both the central and local levels. Across the world, countries decentralise as they develop. But it is the experience of East Asia’s spectacular growth and some of their highly decentralised governments that draws out most clearly the linkages between development and decentralisation and provides the most relevant lessons. This first article in the three-article series lays out the context for decentralisation in Bangladesh and shows how decentralised many East Asian countries are. The second article, in the next issue of Policy Insights, will show how decentralisation supported development and growth in East Asia and helped create the East Asian miracle. The third article will draw on the lessons of East Asian decentralisation, of both successes and failures, and suggest a course to implement decentralisation in Bangladesh. It is worth noting that while these articles will draw extensively from data and economics, this author’s primary motivation comes from his experience of working on East Asian development for eight years and observing and learning first hand about the energy and activism of local governments in that region.

Decentralisation in Bangladesh provokes strong views and thus it may be worth addressing some of them at the very start. Most common among these are decentralisation is politically unrealistic because both the Central government political leaders in Dhaka and the Members of Parliament, who are unwilling to share power in their constituencies, will obstruct it. Another objection is that there is not enough local level administrative and technical capacity. A third objection may be that we are a small, homogenous country and there is no need to have decentralisation.

There are several responses to these objections. First, on the politics. De jure, local governments in Bangladesh already have a firm basis in Bangladesh in the constitution and several legislations as it will be discussed in the last article. However, de facto, it is true implementation that lags well behind, indicating the opposition to decentralisation that exists. Second, a more appropriate design of decentralisation than currently exists can address both political opposition and the technical capacity constraints. Currently, our decentralisation is principally based on Upazila governments. By focusing on this small-sized tier we exacerbate political and capacity problems. A key lesson from the East Asian experience is indeed that decentralisation needs to take place to the right tiers.

This article suggests the 64 district governments can be the most effective sub-national government tier for two reasons. They are large enough in size and population to create political space for both Members of Parliament and local governments. This will help to diffuse political opposition. Their larger size can also address capacity constraints by being able to draw on greater administrative and economic resources. Creating powerful district governments will also respond to the third objection. Bangladesh, with a population of 161 million people, is not a small country: it is significantly larger by population than the Philippines, South Korea, Vietnam, and Thailand– all countries significantly more decentralised. Further, uneven development in Bangladesh has led to heterogenous economic conditions across the country which calls for more differentiated development strategies across regions. A decentralised government framework of 64 powerful district governments – we could even title them provincial governments – would be similar to the 81 provinces of the Philippines or the 61 provinces in Vietnam. The third response to these objections is we probably do not have a choice: future development will have to be more knowledge intensive and regionally balanced. But regional development, especially city and town development, needs detailed knowledge of local conditions and local “preferences” or needs of the people and of local conditions. It will need to harness the energy of the people which can only be possible if the local governments have power. It will also need effective coordination. It will not be possible for the 35 development related Ministries headquartered and sitting in Dhaka to provide this coordination for the 64 districts, the 340 city and municipal corporations, and the 492 Upazila governments across the country. In closing, it is worth noting that creating powerful district governments would also restore the vision of the founder of the country who had envisioned such governments.

…uneven development in Bangladesh has led to heterogenous economic conditions across the country which calls for more differentiated development strategies across regions.

But what about the opposition of the Dhaka based central government political elite? As once our former Local Government and Rural Development Minister, Syed Ashraful Islam laughingly – and I believe sarcastically – told me at a seminar I was moderating in Washington D.C., decentralisation was one issue where the Awami League and the BNP leadership were united: they opposed it. How does one overcome this opposition? There are two answers to this. First, the political views of even the elite evolve, often under pressure during change. Thus, countries such as China, Indonesia, and the Philippines became decentralised as a part of major political transitions and democratisations: China after Mao, Indonesia after Suharto, and the Philippines after Marcos. Second, the main issue is not whether decentralisation is politically realistic. The main issue is whether development for a large country is possible without decentralisation. If the answer to the second question is no and a country like Bangladesh cannot decentralise, it will become stuck in what we economists call a middle-income country trap.

Before closing this first section, it will be useful to clarify some definitions. First, when we refer to East Asia it will be to the larger developing countries of East Asia: China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. At times we will also refer to Japan and South Korea. It is worth noting that all these countries, except China and Indonesia, are smaller than Bangladesh by population size. The two exceptions, China and Indonesia, are huge in terms of land size and population.

How relevant are these countries’ examples for Bangladesh? As an old Chinese saying goes “Shan gao, huangdi yuan” — “The mountains are high, and the emperor is far away”. Indonesia is an archipelago of 18,307 islands that span just over 3,000 miles from the East to the West. Thus, to some extent, decentralisation would be natural in these countries. While this argument is true, it ignores history: that both China and Indonesia were highly centralised countries until the reforms of Deng Xiaoping in China and the post-Suharto democratic reforms in Indonesia. Another argument can be that China and Vietnam are highly disciplined one-party run states and thus are not examples applicable to democratic countries such as Bangladesh. But the point is that underneath the one-party state there are highly decentralised provincial and prefecture governments that engage in fierce competition with one another. So even when their political systems are different there are institutional designs which can be useful even in other contexts. And that is the case in East Asia where highly heterogenous political systems have also adopted decentralisation to varying degrees.

Second, when we refer to decentralisation we will be referring to a narrow version of fiscal federalism and fiscal decentralisation. We will be focusing on “provision decentralisation” (Gadenne and Singhal, 2013) or “expenditure decentralisation”. Under this definition, local governments have significant discretionary fiscal resources and administrative authority to provide critical public services and functions, but not necessarily the authority to tax. Thus, when we refer to decentralisation, we will not be referring to taxation decentralisation or political federalism, where, under the latter, subnational governments’ leaders need to be elected and have formal political autonomy from the central government. At least some degree of taxation decentralisation can be extremely important as we shall see when we discuss East Asian experience in the next article. Political decentralisation or federalism is essential for democratic countries such as Bangladesh and India in South Asia or Indonesia and the Philippines in East Asia. However, the data suggests that it is “provision” or expenditure decentralisation that has the most beneficial effects. The reason for this is probably that taxation decentralisation is complex, and implementation is difficult. Political federalism and election of local officials are important for large and heterogeneous states. Even so, when countries have political federalism they may not have fiscal decentralisation and the beneficial effects become limited. This is one reason India and Pakistan are federal states that fall well short of effective decentralisation- because they have not decentralized fiscal and administrative authorities to lower levels. Fiscal decentralisation in India and Pakistan stop at the state or provincial levels that are huge entities, larger than most countries of the world.

The Bangladesh context: achievements and challenges

Bangladesh was famously declared to be “a test case for development” at the time of her independence. As of now, Bangladesh has passed the test impressively. Per-capita income and food production have grown nearly three-fold since independence. We have emerged as an important manufacturing power in textiles, the second largest source of ready-made garment exports in the world. We have been included by Goldman Sachs as one of the “Next Eleven” group of dynamic emerging economies. Although still nascent, the economy has started towards diversity, exporting some 1400 products. No less impressive have been poverty reduction and human development: extreme poverty rates have declined by two-thirds from more than 40% 30 years ago to about 13% in 2016. We have achieved near universal primary school enrollment and gender parity. Perhaps the most telling, life expectancy now stands at 72 years, higher than in India and Pakistan. We have been officially classified as a lower-middle income country in the World Bank’s classification for a few years now and have recently started the graduation process out of the Least Developed Country Group under the United Nations Classification.

Even so, Bangladesh is at an early stage of development and poverty and growth will remain deep challenges. Consider the poverty line of internationally comparable Purchasing Power Parity Dollar 3.20 consumption per person per day, which is roughly estimated to be the average national poverty line for the World Bank classified lower middle-income countries, the group to which we now belong. This poverty line is equivalent to a modest Tk. 11,408 of monthly consumption for a family of four. More than half our population live below this level.

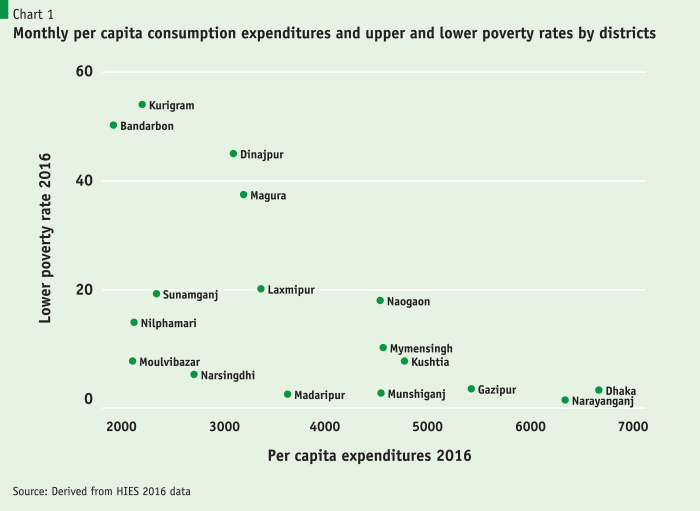

Thus using the lower middle-income country poverty lines, more than half of our population is poor and they are regionally concentrated. More than half of the poor people live in one-fourth of the districts concentrated in the North, North-West and the Chittagong Hill Tracts (Chart 1). Given Bangladesh’s population density and the vulnerability of our coastal areas, there will be little scope to use out-migration to address poverty in the poor districts. Instead, a more spatially balanced local area development strategy will be needed to create good jobs and higher incomes in poorer districts. Local governments will need to be strengthened and made more responsive to development challenges as we will elaborate below.

More than half of the poor people live in one-fourth of the districts concentrated in the North, North-West and the Chittagong Hill Tracts…

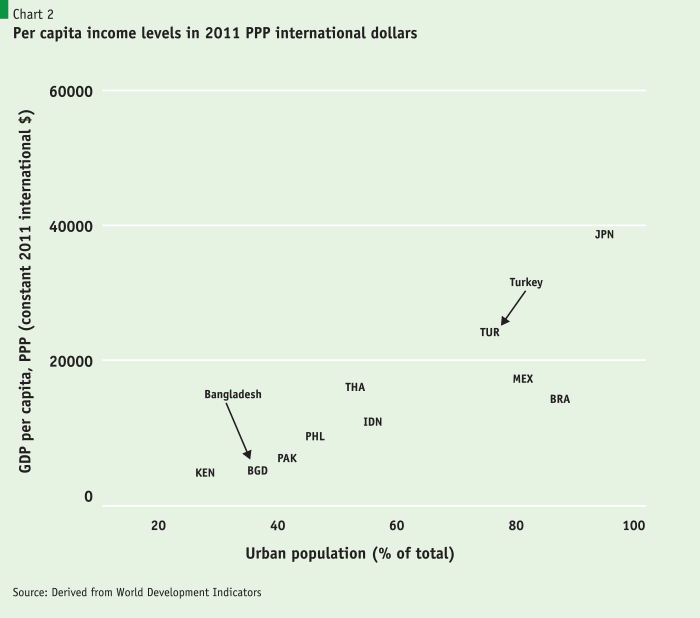

Despite the acceleration of growth in recent years, Bangladesh still has a long way to grow even to be an upper-middle income country. A key task will be sustaining the acceleration in growth rates to 7% per annum in recent years. Although there is an uncomfortable inconsistency between this growth rate and the sluggishness of real wages in the economy, let us take it at face value. Bangladesh’s per-capita income in internationally comparable 2011 dollars today is PPP$3,523 (Chart 2). Upper middle-income Turkey’s per-capita income is PPP$25,129. If Bangladesh can sustain its 7% growth rate, Bangladesh will need 29 years – i.e. till 2046 – to reach Turkey’s per capita income level.

To sustain 7% income growth over three decades in future, the quality of growth will need to be improved. Raising productivity and improving human capital will be critical. We will have to make sure that not only are the children going to school but also they are actually getting a good education and graduating to higher education. We will need to see that not only are there medical clinics available in small towns and villages but also there are doctors and medical supplies available there. We will need not only to build roads and infrastructure, but also to maintain them well and not let them deteriorate frequently as it happens now. To enable all this to happen we will have to ensure that governments of districts and Upazila towns are proactive and energetic in providing these services, attracting private investment, and creating and finding jobs for their constituencies. But, as it happens, these are all areas where Bangladesh is lagging.

Bangladesh is extremely centralised

To meet the challenges discussed above, Bangladesh will have to overcome one over-arching challenge in particular: extreme centralisation. There are two major indicators that point to Bangladesh’s extreme centralisation compared to other countries. The first is the excessive concentration of people and economic activity in Dhaka city. The second is the extraordinarily high share of public expenditures allocated by the Central government. Thus, while many of our future development battles will take place in the different cities, towns, and districts of Bangladesh, the governments there will have neither the authority nor the capacity to meet these challenges.

Dhaka city is the capital of Bangladesh and by far its largest city, which makes it, in the urban economics literature, Bangladesh’s primate city. Although Dhaka’s two city corporations coexist along with the other nine city corporations and 329 municipalities of Bangladesh, Dhaka’s importance is overwhelming. It accounts for about 31% of the country’s urban population and by some estimates between a quarter to a third of the national GDP. In some ways this may be seen as natural: Bangladesh is a geographically compact country. Dhaka is located at the center and is a hub. Market forces may be producing this outcome due to scale and agglomeration economies. However, Dhaka is also by far the most densely populated city in the world. Costs of congestion in Dhaka are high: 2.6% of GDP (2013 estimate) – or more than $5 billion – in traffic costs alone. Pollution, urban slums, stagnant poverty rates in urban areas suggest that quality of urbanisation is extremely poor. Dhaka is regularly ranked among the least livable cities of the world.

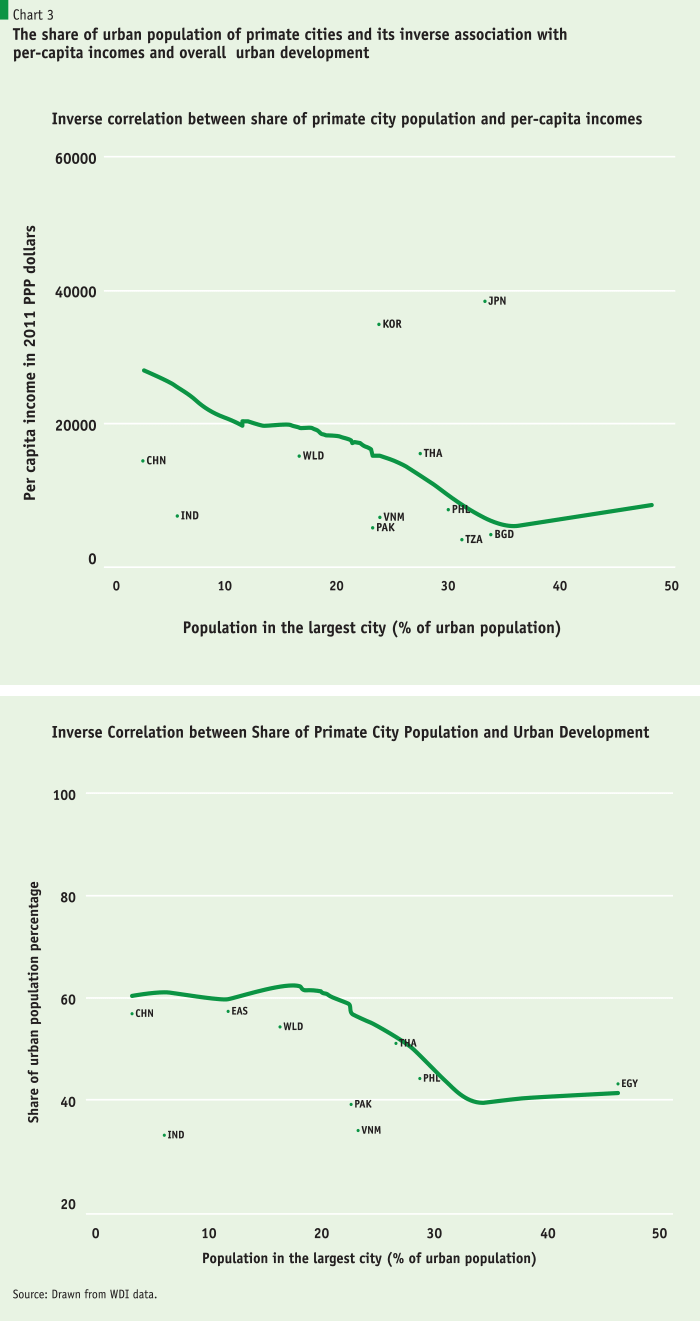

Bangladesh’s primate city Dhaka’s share of Bangladesh’s urban population at 31% is exceptionally high by international standards. This is especially so if we consider larger countries with population more than 50 million as shown in Chart 3. Following other research if we predict the population size of Dhaka, by using the country’s population, land size, and per-capita income levels then Dhaka turns out to have 70% higher population than predicted by international norms (Ahsan, 2018).

Bangladesh’s primate city Dhaka’s share of Bangladesh’s urban population at 31% is exceptionally high by international standards.

What are the consequences of an excessively large primate city? Data suggests that it probably means lower urban development and lower income levels. As the economist Vernon Henderson pointed out in the early 2000s, it is the size and growth of the primate city that matters for growth and development. This seems to be confirmed when we analyse recent international data from 2016 which suggests that while urbanisation and economic development are tightly correlated – as shown in Chart 2 – the primate city and income can be inversely correlated to income levels especially if the primate city is excessively large. Interestingly, one channel through which this effect may happen is the fact that an excessively large primate city impedes overall urban development. Chart 3 illustrates both these trends. The top panel shows per capita incomes becomes progressively lower in countries whose primate cities share of urban population becomes larger than 20-21%. The bottom panel is even more dramatic: urban population share of countries drop sharply once the primate city’s urban population share crosses 20-21 %. It is worth stressing here that while the figures below are scatterplot diagrams, regressions using panel data of 70 large countries with populations greater than 50 million suggest that increasing the population share of the primate city by one percentage point is associated with a decline of the share of urban population by more than 0.7 percentage point. (Ahsan, 2018). If this average result holds for Bangladesh, than the fact Dhaka’s urban population share is 31% of the urban population instead of the 21% predicted by international norms, may have lowered Bangladesh’s total urban population share by 7 % points. Thus, according to these results, the overgrowth of Dhaka may be significantly hurting overall urban development.

There are probably two reasons for Dhaka’s overgrowth. Economics literature suggests that a city can become overgrown beyond the benefits of agglomeration and economies of scale because the effects of “circular cumulative causation”. This means that as a city grows and attracts more industries, more services, more human capital, this process feeds on itself. Even though it may be more profitable for a group of firms or skilled people to move to another city outside Dhaka it is not advantageous for single firms or small groups. Thus, even though costs outweigh the benefits of growing the city, for individual or small groups of firms and skilled labour the benefits are more than the costs.

It is, thus, likely that Dhaka is overgrown, but less because of economic forces than by the concentration of power in Dhaka. Not only is Dhaka the political capital of the country, it is also the seat of decision making of all major public and private agencies in the country which are attracted there by the proximity to power. As a result, most firms find it beneficial to have proximity to power, and this causes more services and human capital to be located here than in other cities, resulting in lower overall urban development.

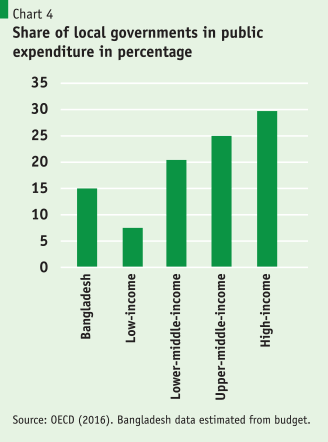

The second indicator – more widely used and intuitively persuasive than the first one –suggests Bangladesh is highly centralised in the share of Central government in all public expenditures. By this measure, our Central Government’s power is all-encompassing as it spends more than 90% of all government expenditures. This means that the nearly 900 other cities, municipals, and Upazila governments have less than 10% of the national budget for their use. Most of those expenditures go for salaries and as a result, local governments have virtually no role in development.

Across the globe as countries develop, decentralisation and the share of local government expenditures increase. As Chart 4 below shows, for high-income countries local government expenditures are 30% of all public spending. For the upper-middle-income group, the share is 25 % while it is 20% for the lower middle-income group to which Bangladesh belongs. Bangladesh is clearly an outlier in the lower middle-income group as the share of local governments in overall government expenditures have averaged between 7% to 8 % in the past years. As incomes rise, the demand for effective local governments from citizens rise and so does the capacity to decentralise with better education and institutions. Politically, the transition from authoritarian regimes to democratic governments, as it happened in South Korea and Indonesia in the late 1980s and late 1990s, also boosts decentralisation. The important takeaway here is decentralisation and economic growth for middle-income countries are likely to go hand in hand. To use jargon, they are endogenous.

It is neighbouring East Asia’s experience with decentralisation, however, that provides the most thought-provoking lessons for Bangladesh. There are at least three reasons for this. First, the East Asian Miracle – as the story of East Asia’s spectacular growth and progress is often referred to – gives highly relevant examples of how to sustain growth over decades for middle-income countries. Second, East-Asian economies are highly decentralised, especially among developing countries, and this gives lessons on the role that decentralisation has played in their development as well as lessons on the design of decentralisation. The experiences of East Asian development may have particular relevance for Bangladesh as many East Asian countries and Bangladesh share some features.

These countries are densely populated tropical countries, where agriculture has thrived and grown robustly based on small farmers producing chiefly high-yielding rice cereals. In recent decades, Bangladesh is also following East Asia in becoming an export-oriented manufacturing power for growth and bringing structural changes in the economy. Henry Kissinger in his magisterial book On China refers to two countries, Bangladesh and Vietnam, as now well placed to host the labor-intensive manufacturing that is moving out of China due to high wages. Bangladesh’s relatively impressive human capital development, greater female participation in the labour force, and rapid urban population growth all follow East Asia’s development trajectory. Historically also there are similarities: like several East Asian countries, Bangladesh was born out of liberation war that created a flatter, mobile society compared to other South Asian countries.

East Asian countries are among the most decentralised

During the last 50 years the developing countries of East Asia achieved historically unprecedented growth and poverty reduction. Between 1971 and 2016, when Bangladesh’s per capita income grew by three times, per capita incomes in East Asian developing countries grew by 13 times, i.e. 4 times faster. Because of this growth nearly 900 million people came out of poverty and their poverty rates fell to about 4%. 80% of global poverty reduction took place in East Asia. The middle class grew exponentially and now East Asia’s middle-class number nearly 1.5 billion people or about half of the world’s middle class. As the labor force became educated and government invested in technology and infrastructure, these countries have become sophisticated technology producers and now supply a third of the world’s capital goods.

The broad factors explaining the East Asian medical miracle have been widely discussed, including in an article in the first issue of Policy Insights (April, 2018). These countries saved and invested a very high share of their GDPs in building infrastructure, industrial capacity, cities and human capital. They created rules and regulations and supportive states under which private enterprise flourished. They also embraced globalisation with fervor and captured a dominating share of world trade and foreign investment flows that provided much-needed technology.

However, these explanations omit a critical detail: the role local governments played in creating the East Asian miracle. This feature has been especially true in the last 25 years after political and economic reforms started in East Asia in China, South Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, and later in Indonesia. Japan, whose heyday of growth was earlier in the 1950s through the 1970s, is also highly decentralised as we will see below. Decentralisation in East Asia often accompanied political reforms after the overthrow of authoritarian rulers such as Marcos, Suharto, Park Chung Hee. In China and Vietnam, they were an integral part of the reforms launched by Deng Xiaoping or the Vietnamese Communist party when they launched market economy “Do Moi” reforms in the early 1980s.

Today, governments of East Asia have decentralised significant parts of the economy to the local governments.

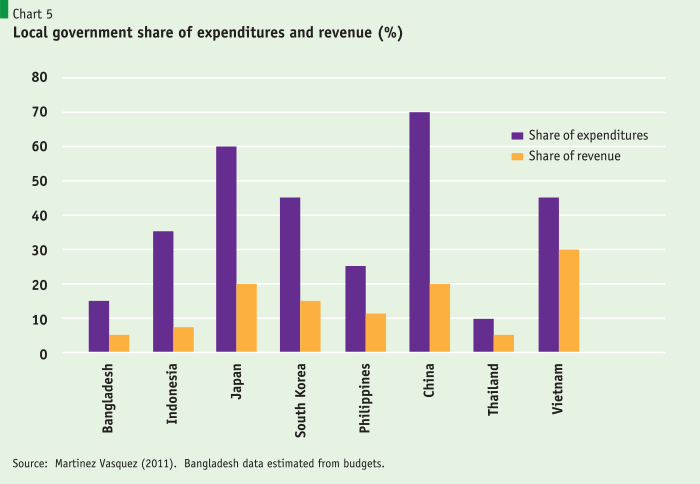

Today, governments of East Asia have decentralised significant parts of the economy to the local governments. Subnational governments in countries play a key role in deciding and implementing investment, fiscal, and regulatory policies. These countries range from the highly, fiscally decentralised economies of China and Vietnam to the relatively more centralised ones such as Thailand and Malaysia. Overall, however, a picture is clear from Chart 5 below. Except for Thailand, sub-national governments in Bangladesh have far fewer expenditure responsibilities than in any of the East Asian countries. Sub-national governments in China, South Korea, Vietnam, and Japan spend between 40% to 70% of all government expenditures (the taller bars on the left). Indonesian local governments spend more than a third of government expenditures while the Philippines local governments spend about a quarter of the general government budget. In China and Vietnam, provincial, prefecture, or county governments have the principal responsibility and budgets for agriculture, forestry, irrigation, fisheries, power, water, employment, education, and health. Provincial and county governments spend more than 80% of expenditures in health and education and about 70% of public investment expenditures. In Indonesia, District governments are responsible for health, education, environment, and infrastructure and in the Philippines for health, social services, environment, agriculture, public works, education, tourism, telecommunications, and housing.

Second, East Asian economies have also set up elaborate sub-national governments starting with provincial governments. China has 23 provincial governments, 9 provincial level administrative units– including the 4 large cities – and more than 3000 prefecture or county governments that equally share the 70% of the budgets allocated to local governments. Another large country, Indonesia, with a population of 261 million people, is governed by 34 provinces, 413 districts and some 98 municipalities. Even countries significantly smaller than Bangladesh, like South Korea (population 52 million), the Philippines (population 103 million), and Vietnam (population 95 million) have also set up an elaborate system of local governments. South Korea has 16 regional governments and 226 city, county and district governments where the heads and councilors are all elected. The Philippines has 81 provinces with elected governors and legislatures. In the case of Vietnam most of the public expenditures and administrative powers have been devolved to its 63 provinces and 710 cities, town, and district governments.

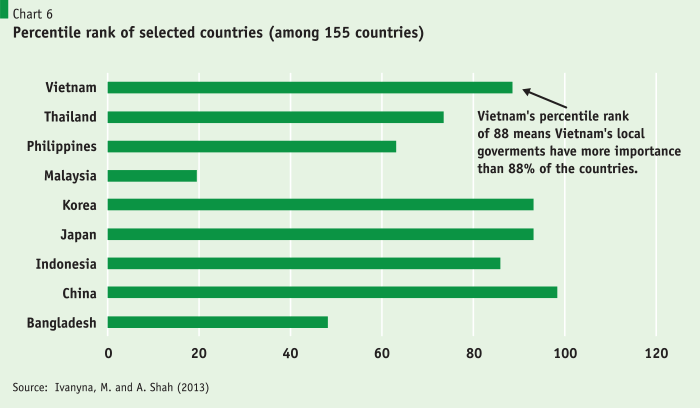

Research integrating government expenditure shares and the legal status of local governments to measure decentralisation in a more comprehensive way confirms East Asia’s decentralisation. As Chart 6 above shows, it ranks China as the 3rd most decentralised in a group of 155 developed and developing countries, while Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, and Korea all rank among the top one-fifth of the countries. Philippines and Thailand rank among the top third, while Bangladesh ranks in the middle. Bangladesh’s relatively higher rank here than when considered purely by fiscal decentralisation is due to its strong laws and elections underpinning Upazila and Union council governments. The one exceptional low ranking East Asian country here is the relatively small sized Malaysia which has a unique set of characteristics in being a resource-rich and racially highly heterogenous country. Ironically, however, Malaysia was created as a collection of princely states and designed as a federal system with elected leaders. Over the years, though, power was transferred away from the States to the center.

Concluding thoughts and a preview

This article, the first in a series of three articles, has tried to set the context for the argument why Bangladesh has to decentralise to sustain its growth and become an uppper middle income country. It has shown how Bangladesh is extremely centralised and how that is adversely affecting overall urban development. It has then provided evidence to show that some of the dynamic East Asian countries are among the most decentralised not only among developing countries but also among all countries. In the next article , we will explore five channels through which decentralisation has helped East Asian developments. These are- helping create ownership of the local economy and reforms, spurring intense competition among regions to grow, encouraging piloting of policy reforms and experimentation, helping develop and identify leaders, and finally promoting high quality urban development.

The third and final article will draw lessons from the East Asian experience and provide some forward looking recommendations for Bangladsh. The key lesson is decentralisation, while necessary, is not a panacea and good design will be critical for its success. Preparation and a gradual process focusing on some selected aspects – e.g. on expenditure decentralisation rather than the whole and preparation will be key. An important issue to address will be decentralising to the right tier of local governments. The lessons of East Asian experience suggests that decentralising to such a small tier of government undermines the effectiveness of local governments. Rather decentralising to the districts as the principal tier will create more effective local governments. Such a move will also restore the vision of the founder of the country.

Selected references

Ahsan, A. 2018. “What Does Bangladesh’s Economic Geography Imply? An Empirical Exploration,” ppt and forthcoming.

Ahmed, T. 2012. Decentralization and the Local State: Political Economy of Local Government in Bangladesh, Agamee, Prakashani.

Chibber, A. 2016. “Notes on Federalism”, ADB, mimeo.

Henderson, V. Journal of Economic Growth (2003) 8: 47.

Ivanyna, M. and A. Shah. 2013. “How Close Is Your Government to Its People?” Worldwide Indicators of Localization and Decentralization,” Mimeo.

Gadenne, Lucie and M. Singhal, 2013. “Decentralization in Developing Economies”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 19402

Kissinger, Henry. 2011. On China, Penguin.

OECD, 2016. Sub-national Governments Around the World: Structure and Finance, Paris.

World Bank, 2005. East Asia Decentralizes, Washington D.C. 2005.