Promoting competition for inclusive development

By

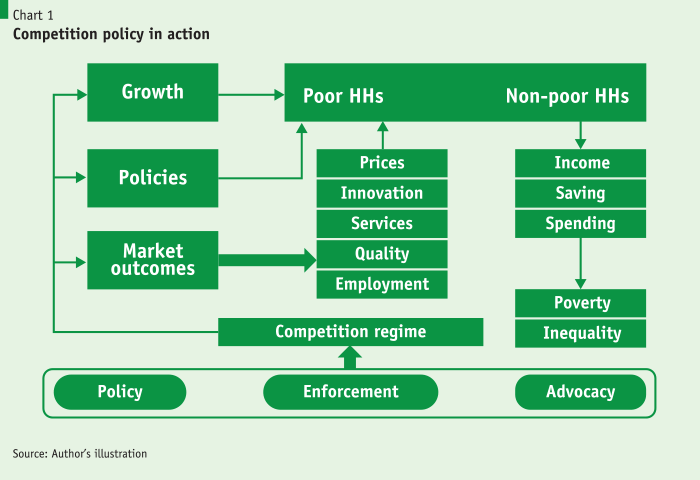

Competitive markets are widely regarded as a major force for driving economic growth, augmenting efficiency for enhanced productivity, and promoting consumers’ welfare. Because of various imperfections, markets often cannot generate desired outcomes and need interventions. Effective implementation of competition policy is one of the most recommended strategies for ensuring a healthy competitive environment.

A set of policies and instruments that are intended to preserve and promote competition among market players are generally referred to as competition policy. In practical terms, it involves efforts at tackling cartels or other collusive practices affecting prices and other market outcomes, preventing mergers that could result in significant lessening of competition, and dealing with actions including state support, which can exert undue market power by one or a small group of actors. Its major policy instruments include: a competition law specifying rules to restrict anti-competitive practices; an enforcement mechanism, usually backed by an authority; and competition advocacy raising awareness and advocating for reforms to improve competitive environment.

Generally, competition is known to have a positive impact on total factor productivity and thus growth. By lowering prices and improving market outcomes, it can help low-income households

Competition policy can act as a direct and indirect contributor to growth and inclusive development. Generally, competition is known to have a positive impact on total factor productivity and thus growth. By lowering prices and improving market outcomes, it can help low-income households (Chart 1). It has been argued that good governance, macroeconomic stability, investment in human development, and social policies to protect the poor are important for promoting economic growth and shared prosperity, but they may not be enough to improve the welfare of the poor (World Bank and OECD, 2017). In this context, competition policy and its effective enforcement can play a critical role. Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz thus aptly observes, “strong competition policy is not just a luxury to be enjoyed by rich countries, but a real necessity for those striving to create democratic market economies”. In the early-1980s, only 15 countries had enacted competition laws. This number increased to about 130 over the past three decades.

The need for a strengthened competition policy regime in Bangladesh

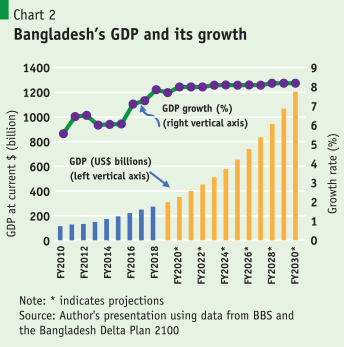

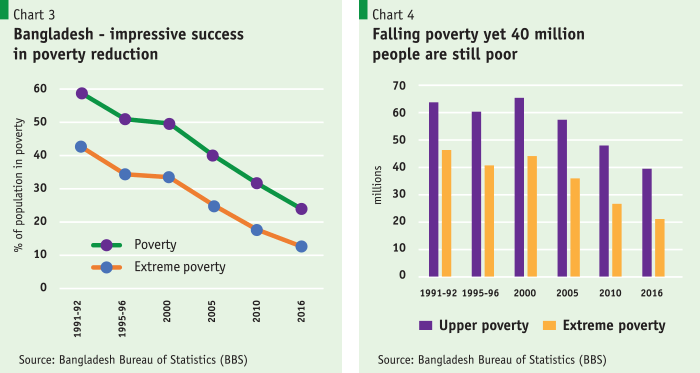

Bangladesh has made spectacular strides forward in its economic development. From a fragile socio-economic set up at independence, it has emerged as ’development surprise‘. Its economy has grown on average at an annual rate of 5.6% for the past three decades or so, with the comparable growth rate for the past 10 years being more buoyant at 6.3%. This means a mere $35 billion economy of the mid-1990s has grown to a sizeable $275 billion today (Chart 2).  During the same time, per capita income registered more than a five-fold rise from $320 to $1,715. The dependence on foreign aid declined from around 8% of GDP in the 1980s to just around 2%. While in the mid-1990s more than half of the population lived on less than the nationally determined poverty line income, it fell to 24.3% in 2016 (Chart 3). Compared with many other countries at a similar stage of development, Bangladesh has made faster progress in various social and human development indicators. The rising per capita income enabled Bangladesh in 2015 to move up into ’lower-middle income‘ from ’low-income‘ economies as classified by the World Bank. It is firmly set to graduate from the group of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) by 2024.

During the same time, per capita income registered more than a five-fold rise from $320 to $1,715. The dependence on foreign aid declined from around 8% of GDP in the 1980s to just around 2%. While in the mid-1990s more than half of the population lived on less than the nationally determined poverty line income, it fell to 24.3% in 2016 (Chart 3). Compared with many other countries at a similar stage of development, Bangladesh has made faster progress in various social and human development indicators. The rising per capita income enabled Bangladesh in 2015 to move up into ’lower-middle income‘ from ’low-income‘ economies as classified by the World Bank. It is firmly set to graduate from the group of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) by 2024.

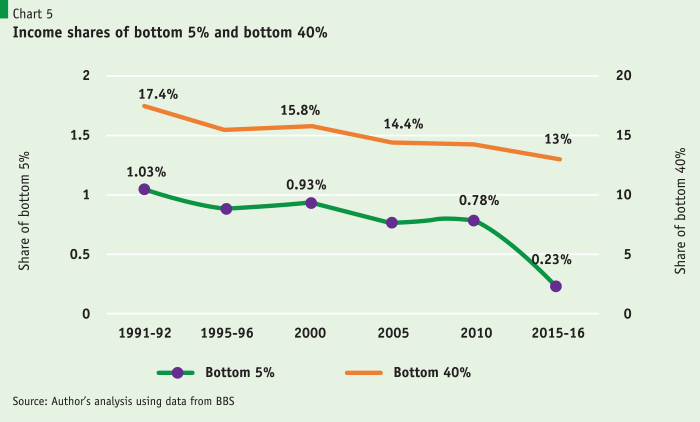

Notwithstanding the impressive achievements, for Bangladesh to sustain high economic growth as part of its inclusive development strategy, tackling inequality remains a challenge. Close to 40 million people still live in poverty (Chart 4) and another 30 million are considered ‘vulnerable’ given the risks and uncertainties they face in slipping back to poverty due to any modest loss of income from any sudden shocks. Along with this, equitable prosperity confronts a major challenge in the face of rising overall income and consumption inequalities. The income share received by the bottom 40% of the population has steadily fallen from more than 17% in the 1990s to 13%. The same share for the bottom 5% of the population has got squeezed to just 0.23% from 1% (Chart 5).

Because of rising inequality, the impact of growth on poverty is falling. It is estimated that during 2005-2010 a 1% GDP growth was associated with 1.8% fall in moderate poverty and 1.5% fall in extreme poverty. But, between 2010 and 2016, the corresponding rates fell to 1.2% and 0.8%, respectively. According to one recent analysis, if the growth had been more equally distributed, poverty incidence during 2010-2016 would have fallen by an additional percentage point (Hill and Endara, 2019).

It is true that policymakers strive for achieving higher economic growth and addressing the concern of rising inequality through various measures. However, one potentially powerful instrument that can help with both the objectives – competition policy – should be put to more proactive use. There is a general recognition of widespread and rising burden of non-competitive effect. For example, while the middle and affluent consumers’ class in Bangladesh is on the rise, it has been estimated that Bangladeshi consumers have to pay 70% above international prices for buying consumer goods in the domestic market with resultant excessive costs estimated at more than $14 billion (Sattar, 2018). This shows the opportunity costs in terms of savings for investment as well as increased demand for additional goods and services.

Lower-income groups are particularly prone to anti-competitive behavior by firms and regulative restrictions (World Bank and OECD, 2017). As they have to spend a greater part of their income on basic goods and services, any anti-competitive practices in these markets will have a disproportionately higher impact on them. By removing inefficiencies in those markets that are particularly relevant to them, competition policy can have a more direct impact on the level and distribution of household welfare. In the longer term, effective competition should boost overall economic growth (through the entry, growth, and expansion of more efficient firms, as well as higher productivity) from which lower income households will be able to benefit more.

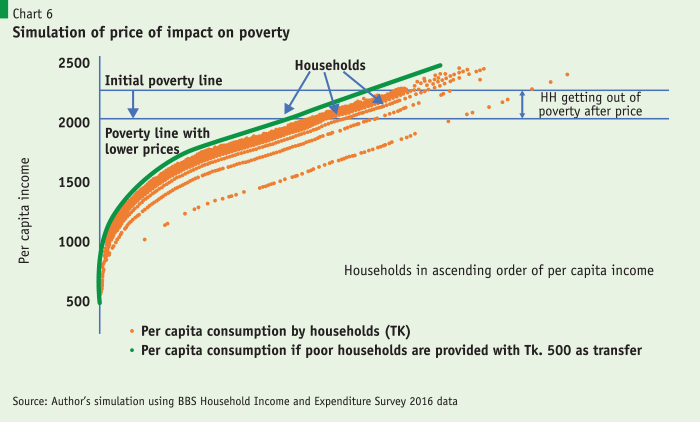

It then follows that competition policy enforcement can complement poverty reduction measures such as social protection spending by the Government of Bangladesh, comprising about 13% of the national budget or about 2% of GDP. Many of these schemes are direct cash transfers to the poor, who tend to use the assistance provided on basic goods. Dealing with anti-competitive behavior in these sectors is important to prevent these transfers from leaking to firms or other actors in the form of anti-competitive profits. Furthermore, if competition policy can help lower prices of goods and services consumed by poor households this can have a very robust impact on their welfare. A simulation exercise using BBS data shows that if prices of necessities fell by 10% along with a rise of monthly government transfers to poor households by Tk. 500, more than 16.5 million people from around 4 million households would be lifted out of poverty. This would also imply the poverty headcount ratio to fall from currently 24.3% to 14% with also an estimated impact of reduced income inequality. As mentioned above, the government is already providing social protection support to many poor and vulnerable households and there are plans for increasing the coverage and allowances. Therefore, the consideration of increasing the transfers by Tk. 500 per month is quite a reasonable one.

Bangladesh can draw lessons from the overwhelming international evidence showing the importance of competition policy in promoting inclusive growth. Using cross-country data, it has been shown that after taking into consideration such factors as macroeconomic environment, financial market development, and political stability, the impact of the intensity of local competition on per capita income lies in the range 2% – 12% (Mónago, 2013).1 World Bank and OECD (2017) provides a useful collection of several analytical and empirical exercises generating evidence from a large number of developing and developed economies. Some of the main findings are as follows.

Evidence on India, based on the variation in regulatory environment across states, finds competition policy elements in product markets to have a significant impact on labour and total factor productivity and thus on economic growth. For OECD countries, the estimated impact of competition policy on TFP growth for a large number of industries is found to be positive. Similarly, a report by the Australian Productivity Commission quantifies the expected benefits from competition reforms as an annual gain in real GDP of 5.5% and consumer welfare gains by AU$9 billion. For Croatia, eliminating anti-competitive regulation in energy, telecommunications, and transport would be associated with an increase GDP per capita by 1.35 –2.77% (De Rosa et al., 2009).

In addition to growth effects, there is also ample evidence of competition policy having positive impact on consumers’ welfare and pro-poor outcomes, and failure to apply it resulting in adverse consequences, particularly for poor households. For example, South Africa experienced a decline of approximately 27% in prices of health care products after an anti-trust intervention by the authorities (OECD, 2003). On the other hand, consumer welfare loss for Mexico due to weak competition in the telecommunication sector has been estimated at an average of about $26 billion per annum over the period 2005–09, equivalent to 1.8% of yearly GDP (Stryszowska, 2012). Again, an analysis of excessive market power in Mexico for a range of basic products finds the net consumer welfare loss for the poorest groups being 20% higher than that for the richest groups (Urzua, 2013).

Overall, World Bank and OECD (2017) estimates show economic harm caused by cartels that are already detected in developing countries is substantial as the affected sales to GDP ratio can reach up to 6.38%, while excess profits resulting from unjustified price overcharges reach up to 1% of GDP. If the consequences arising from the cartels that are not detected yet were taken into account, the total damage could be at least four times larger.

As Bangladesh economy is rapidly growing, failure to ensure a competitive environment could result in massive economic consequences. Major cartels prosecuted in developing countries since the mid-1990s include a variety of products and services, the demand for which is also growing apace in Bangladesh. These include, among others, bricks, cargo transportation, cement, energy, health care, cable tv services, generic drugs, security guard services, transportation, steel, bank interest rates, cooking oil, salt, plastic pipes, freight forwarding, sugar, internet service, sand and construction materials, soft drinks, etc. Along with cartels, there are many other forms of anti-competitive practices. The experience from the developing countries would thus suggest the need for putting in place an effective competition regime.

Salient features of the current policy regime

Bangladesh’s competition policy regime is relatively new. The Competition Act was enacted in 2012 (Act No. XXIII of 2012) to ensure competitive environment and to prevent, control and eradicate anti-competitive practices. Under this Act, the Bangladesh Competitive Commission was established, clearly delineating the duties and functions of the Commission.

The prohibition/regulation of three broad anti-competitive practices that have been specified in the Act are: anti-competition agreements (section 15); abuse of dominant positions (section 16); and anti-competitive combinations (section 21). Anti-competitive agreements are defined as direct or indirect collusions in respect of production, supply, distribution, storage, acquisition or control of goods or provision of services, which cause or are likely to cause an adverse effect on competition. These include, amongst others, price fixing arrangements, bid-rigging agreements, market share/allocation agreements, tie-in-sale arrangements, exclusive supply and distribution agreements etc. Section 15 also specifies that the prohibition/regulation will not apply in protecting intellectual property rights [section 15(4) (i)] and protecting the right of any person to export goods [section 15(4) (ii)].

One important feature of the Competition Act is that it allows the Commission to inquire into anti-competitive practices based on receipt of any complaint or its own initiative

Types of abuse of dominant positions are mentioned in section 16, which includes unfair or discriminatory conditions in purchase or sale of goods and services; limits or restricts production of goods and services or technical or scientific development relating to the goods and services; actions to restrict market access by others, etc. Abuse of dominance could result in such practices as charging excessive prices over intellectual property rights, price discrimination, predatory pricing to deter market entry or eliminate competition. Finally, section 21 deals with combinations that can cause adverse effect on competition. These combinations include mergers, acquisitions and consolidation schemes. The Act (section 22) also stipulates that if an anti-competition arrangement is committed outside of Bangladesh causing adverse effect in the relevant market within the country, the Commission can enquire into the matter in accordance with laws and rules of both the countries. With already a substantial import volume – close to $50 billion – growing strongly, this can also be an important area of anti-competitive practices that might need attention.

One important feature of the Competition Act is that it allows the Commission to inquire into anti-competitive practices based on receipt of any complaint or own its own initiative [section 8(b) and 8(2)]. Thus, proactive initiatives by the Commission are within its mandate. Another salient aspect of the Act is the recognition of the need for interactions with other statutory bodies and specifying the authority of the Commission. Section 14(1) states, “When any person raises any objection that any course of proceeding of any statutory body or any decision of such body is contrary or likely to be contrary to any of the provisions of this Act, such statutory body may, on its own motion, refer the issue, suspending the continuation of the proceeding to the commission for taking proper action on it.”

The Act provides guidelines for how complaints, inquiries, and punitive actions will be conducted (Chapter IV). Provisions for review of orders of the Commission and appeal procedures are also stated (Chapter V, section 29 and 30).

It is, however, important to recognise that given the scope of the mandate of promoting a competitive environment, the Commission’s work cuts across various policy arenas. For example, trade and industrial policies do have a direct influence on the competition regime in the country. Again, fiscal and monetary policies and sector-specific reforms also have profound implications. How the outcomes arising from these existing policies interact with the overall ambition of the competition policy regime is something that deserves serious consideration. The other issue is coordination and potential conflicts with sector-specific regulators.

The Competition Act quite appropriately emphasises on raising awareness. In specifying duties, powers and functions of the Commission, it states one task as to “take necessary plan of actions for developing awareness among the people about the matters relating to competition by the way of dissemination, publication and other means” [section 8 (g)]. It further mandates the Commission to develop mass awareness by conducting research, seminars, workshops and other means [section 8(h)].

Way forward for Bangladesh

International experience suggests convergence in the scope, coverage and enforcement of competition laws and policies worldwide (UNCTAD, 2010). This is due to such factors as (i) adoption of liberal policies and growing awareness about the importance of competition policies in promoting efficiency and thus more productive utilisation of resources, (ii) greater emphasis on consumer welfare, (iii) the universal condemnation of collusive practices, and (iv) a more prominent role for competition authorities in advocating competition principles in the application of other governmental policies. From these perspectives, it follows from the above that the existing Competition Act provides an important basis for developing a proactive competition regime in Bangladesh.

In any dynamic economy, the task for competition authorities can be quite involved given the interlinkages and interactions of different factors (including the national objectives of industrialisation and economic development promoting certain sectors) with the issue of competition. This is further exacerbated by the need for using economic frameworks in combination with empirical evidence in determining anti-competitive practices. Developing specialised knowledge for certain sector-specific complex issues is a prerequisite for effective regulation. Consequently, many countries have different agencies dealing with certain sectors.

Developing a modern and proactive competition policy regime therefore may be considered as work-in-progress through sustained capacity building in some identified priority areas and expanding the scope gradually. It has been argued that countries at different level of development and governance capacities require different types of competition policies (Singh, 2002). That is, a one-size-fits-all approach will be inappropriate. As it may not be possible for a developing country like Bangladesh to incorporate all aspects of competition policy, a staged approach may be helpful. At an early stage of implementation, competition authorities need to strengthen capacities and build the trust of the public. This can be greatly aided by placing concerned actions on those practices that clearly hinder competition. Given the national priority of inclusive development, there should also be efforts in dealing with those anti-competitive practices that disproportionately affect poor and vulnerable households.

The sequential approach, however, does not imply that the initial focus should only be in traditional areas, e.g. in those sectors in which today’s developed and/or advanced developed countries had experienced much of anti-competitive practices at their early stage of development. For example, because of technological revolutions, many service sectors are growing rapidly. Competition related issues with them could be a relatively new phenomenon both in advanced and developing countries. However, given the significance of the sector, even developing countries like Bangladesh may need to develop capacities to promote competitive environment in these sectors.

The cross-country evidence of widespread presence of anti-competitive behaviour could indicate that the severity of the problem in the context of Bangladesh has perhaps gone largely unnoticed because of lack of analysis with serious consequences inflicted on the economy and consumers. Under this very likely circumstance, the scope of the work of the Commission is truly enormous.

In going forward, the need for institutional capacity building of the Competition Commission can be hardly overstated. There is the concern of resource constraints of competition authorities not only in Bangladesh but also in many other developing economies. However, considering the potential gains from ensuring a competitive environment, competition-related capacity building should be given a priority. It is not about the capacity building of regulatory authorities only, the overall knowledgebase and expertise within the country on the relevant issues must be developed for effective implementation of the policy regime. It is in this context that the Commission can play a vital role by generating demand from research, advocacy material and other informed inputs. In the absence of rigorous economic analysis behind the cases under investigation, any decisions might be considered as discretionary in nature, affecting confidence of the stakeholders. It is one of the areas where the Commission can proactively engage with the universities, research institutes and other think-tanks to start generating knowledge products, exchanging ideas and identifying scope of research and policy work. While the Commission can demand resources from the government for undertaking specific research and analysis, its intent to be benefited from such work can also help universities and other research think-tanks mobilise resources from various donors and international channels.

In implementing competition policy, political economy factors must be given a serious consideration. Competition brings benefits to consumer groups and to many firms that do not/cannot actively pursue their demands for reforms facilitating their market access and business growth. On the other hand, vested interests favouring status quo can be well-organised to make authorities vulnerable to their pressure. It is thus critical to mobilise support for competition policy through advocacy. For this to be achieved, raising mass awareness amongst potential beneficiaries such as small and medium size enterprises, consumers, and civil society groups is extremely important.

Competition advocacy is also needed to sensitise the government as a whole including various ministries, departments and other regulatory bodies. Within its mandate, the Commission should be able to freely review, provide comments and make recommendations for bringing changes in any proposed laws and existing practices that would contribute to overall competition environment in the country.

Conclusion

Building on a solid track record, Bangladesh aspires to achieve higher economic growth with shared prosperity and sustainable development. The government is strongly committed to reducing poverty and inequality so that all population groups including those that are currently among poor and vulnerable can meaningfully benefit from the growth and development process. This commitment is reflected in Vision 2021, the Perspective Plan of Bangladesh 2010-2021 and in the 7th Five Year Plan FY2016-FY2020. Notwithstanding the spectacular success of the country, inclusive development remains a policy objective to be seriously pursued along with growth acceleration. Effective implementation of competition policy can be a complementary means for attaining these goals.

The Competition Act in place contains many useful provisions for promoting competitive environment. However, what is perhaps most important at this stage is to build capacity for effective implementation of the Act. The level of awareness surrounding competition-related issues among all stakeholders, including the government, private sector enterprises, academics and researchers, consumers’ groups and the general civil society is limited. Given its importance in achieving improved economic efficiency and distributional outcomes, it is high time the competition regime in Bangladesh was strengthened.

This paper is based on a keynote presentation made at a seminar titled “The Role of Competition Commission in Sustainable and Inclusive Development in Bangladesh”, organised by the Bangladesh Competition Commission, held on 9 March 2019.

References

Hill, R. and Endara (2019). “Agricultural growth, manufacturing and migration: assessing poverty reduction in Bangladesh from 2000 to 2016”, PowerPoint presentation slides, Dhaka.

Mónago, T. O. (2013). “Assessing Competition Policy on Economic Development”, Economia, vol. XXXVI, nO. 71, pp. 9-56.

Sattar, Z. (2018). “The Cost of Protection: Who Pays?”, Policy Insights, July issue, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Singh, A. (2002). “Competition and competition policy in emerging markets: international and developmental dimensions”, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development – UNCTAD and Center for International Development Harvard University, G-24 Discussion Paper Series Nº 24, September, New York and Geneva.

Stiglitz, J. (2001). Competing over competition Policy, (2001) https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/competing-over-competition-policy

Stryszowska, M. 2012. “Estimation of Loss in Consumer Surplus Resulting from Excessive Pricing of Telecommunication Services in Mexico.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

Urzua, C. M. (2008). “Evaluacion de los efectos distributivos y espaciales de las empresas con poder de mercado en Mexico.” Mexican Federal Competition Commission. http://www.oecd.org/daf/ competition/45047597.pdf.

White, L. J. (2008). “The Role of Competition Policy in the Promotion of Economic Growth”, New York University Law and Economics Working Papers, Paper 132, http://lsr.nellco.org/nyu_lewp.

World Bank and OECD (2017). A Step Ahead: Competition Policy and Shared Growth, World Bank, Washington, D.C.