Redistributive Fiscal Policies can help reduce income inequality in Bangladesh

By

Development Context

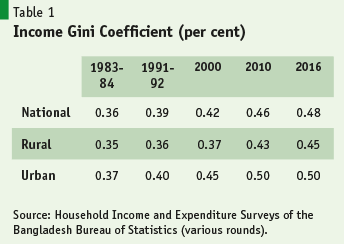

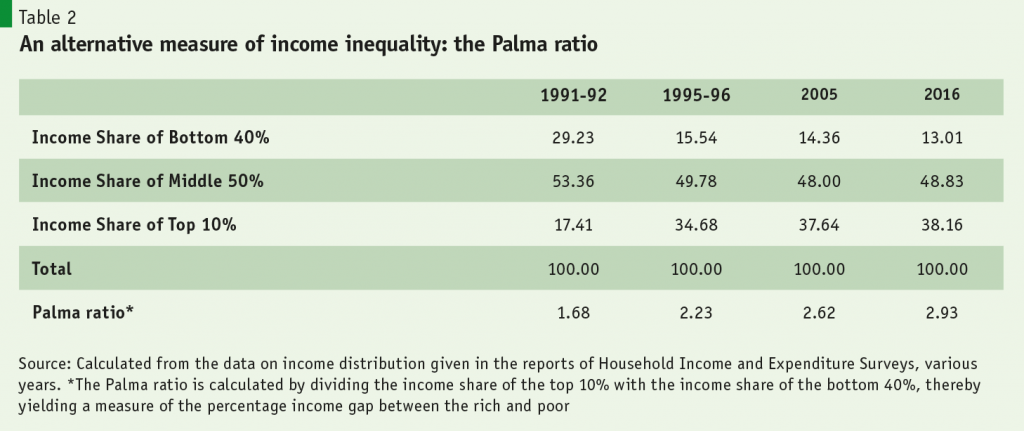

Bangladesh has made tremendous development progress since independence, which accelerated between 2009 and 2022. The progress is reflected in terms of GDP growth acceleration leading to rising per capita incomes, reduction in poverty, and improvements in human capital including literacy rates and life expectancy. Along with this admirable development outcome, a worrisome result is the rise in income inequality, indicated by both a rising Gini coefficient and an increasing Palma ratio (Tables 1 and 2).

Covid-19 seems to have worsened income inequality globally owing to the fact that it disrupted the employment and income opportunities for the poor and low-income group disproportionately more than the rich population.

While the effects of Covid-19 on income inequality across countries are still being calculated, early estimates predicted an increase in Gini coefficient of 1.2-1.9 percentage points per year for 2020 and 2021, signalling an increase in income inequality.

While the effects of Covid-19 on income inequality across countries are still being calculated, early estimates predicted an increase in Gini coefficient of 1.2-1.9 percentage points per year for 2020 and 2021, signalling an increase in income inequality.

Full evidence from Bangladesh is lacking owing to the absence of Household Income and Expenditure (HIES) for the post-Covid period, but partial evidence from independent survey results suggest that the poor and low-income group appear to have suffered proportionately more from the adverse economic effects of Covid-19 than the rich.

The recent surge in global inflation, caused by the combined effects of the Covid-19 disruption of global supply chains and the ongoing war in Ukraine, has put additional pressure on the real income of the poor and the low-income group. Global evidence is clear that inflation tends to hurt the poor more than the rich and Bangladesh is no exception.

Approach to Lowering Income Inequality

In a market economy, income inequality arises from the unequal initial distribution of physical and human capital that tends to get accentuated over time as a larger share of economic opportunities resulting from economic growth is captured by the rich owing to their initial distribution advantage.

The main solution to this inherent inequality of the market economy is for government intervention to re-balance the initial disadvantage of the poor, low-income and vulnerable population through the use of a redistributive fiscal policy.

The basic idea of the redistributive fiscal policy is to secure a proportionately higher share of the government revenues through higher taxation of the income of the rich and redistributing a part of that income to the poor, the vulnerable and the low-income group. This redistribution can happen through a range of social and economic policies including creating job opportunities for this group, giving them better access to health, education, and water supply, and through direct income transfers based on a targeted social protection program.

The best examples of successful use of redistributive fiscal policies come from the experience of countries of Western Europe. These countries raise considerable tax revenues based on a progressive income tax system and combine this with a strong social expenditure program focused on the poor, the vulnerable and low-income group.

Thus, the tax-to-GDP ratios in these countries tend to be in the range of 29% (Switzerland) to 46%, (Denmark) with a progressive personal income tax contributing to much of the revenues. Social spending on health, education, and social protection as a percentage of GDP ranges from 16% (Netherlands) to 31% (France). The results in terms of income inequality performance have been remarkably good. The Gini coefficient of income typically ranges between 0.26 (Belgium, Denmark, Norway) to 0.37 (UK).

Redistributive Fiscal Policies for Bangladesh

The Government of Bangladesh is aware of the need for putting greater focus on lowering income inequality. This is reflected in the fact that the introduction of a redistributive fiscal policy is a core fiscal policy reform underscored in the Perspective Plan 2041 (PP2041). The Eighth Five Year Plan (8FYP) aims at initiating the first phase implementation of this fiscal policy.

8FYP Strategy for Redistributive Fiscal Policy

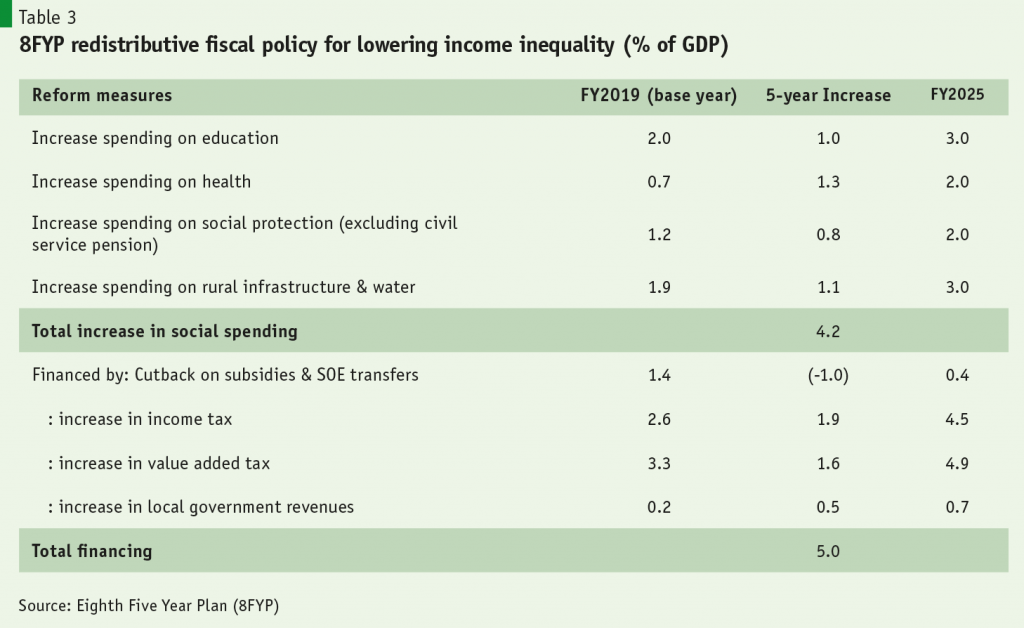

The combination of taxes and social spending that are proposed in the 8FYP to implement a redistributive fiscal policy is illustrated in Table 3.

Spending Priorities

The first and topmost policy priority of the 8FYP is to raise the share of public spending on education and health to at least 3% and 2% of GDP, respectively. The Plan also puts emphasis on the need for major improvements in the delivery of public education and health services through reforms in policies, governance, and institutions.

A second area where the Plan proposes to increase public spending concerns rural infrastructure–rural roads, rural electricity, irrigation, and flood control. Government spending in this area has helped increase farm productivity and food production. The near food self-sufficiency of Bangladesh despite rapid population growth is a testimony to the success of this policy.

Yet, much of the labour force remains engaged in low productivity and low earnings agriculture. There is a need to further diversify agriculture into higher value-added activities and to help transfer surplus labour from agriculture to non-farm activities in rural and urban areas.

Yet, much of the labour force remains engaged in low productivity and low earnings agriculture. There is a need to further diversify agriculture into higher value-added activities and to help transfer surplus labour from agriculture to non-farm activities in rural and urban areas.

This transformation will support both income growth and income distribution by helping increase labour productivity in the economy. Furthermore, the implementation of the water investments proposed in the Delta Plan (BDP2100) will benefit farm productivity and reduce the loss of rural livelihoods and property from flooding and riverbank erosion. Additional spending of 1% of GDP on rural infrastructure is proposed in the 8FYP.

The availability of rural credit is another important determinant of this transformation. The micro-credit revolution has helped the poor to build up assets and protect their consumption, thereby contributing to lower poverty. Nevertheless, the scaling up of formal credit to the rural economy remains a challenge. The 8FYP seeks to improve this.

A third area where public spending is proposed to increase in the 8FYP is social protection. Presently the government spends about 1% of GDP on social protection excluding civil service pensions. The 8FYP projects this to grow to 2% of GDP over the next 5 years.

Financing Strategy for Higher Social Sector Spending

Higher public spending on education, health, rural infrastructure, and social protection by an estimated additional 4.2% of GDP over a 5-year period is a tall order in the present environment of public resource constraint. The 8FYP advocated the following financing strategy.

In the first place, the government spends some 3.4% of GDP on subsidies and transfers, of which 1.4% of GDP is on subsidies and transfers to power and other SOEs including public banks. A core fiscal reform of the 8FYP is to convert the SOEs including the power sector and public banks to profit-making enterprises. These subsidies can, therefore, be drastically reduced and re-channelled to priority social spending as noted above.

Secondly, a major reason for the resource constraint is low tax collection, especially from personal income taxes. The effective income tax rate at present is about only 4%, which is extremely low. Increasing the effective income tax rate to even 10% in the next 3-5 years to the top 10 percentile who own 35% of the national income will yield 3.5% of GDP instead of 1.4% of GDP now.

The effective income tax rate at present is about only 4%, which is extremely low. Increasing the effective income tax rate to even 10% in the next 3-5 years to the top 10 percentile who own 35% of the national income will yield 3.5% of GDP instead of 1.4% of GDP now.

This will require the closing of loopholes that let capital gains escape the tax net, considering all sources of personal income for taxation purpose, and improving tax administration and compliance especially focused on the rich and upper income groups. So, along with corporate income taxation, the total tax on income and profit is projected to grow from 2.6% of GDP in FY2019 to 4.5% by FY2025.

The modernisation of VAT and improving its productivity can yield an additional 1.8% of GDP. Moreover, the introduction of a modern property tax and assigning this to the local governments can be a substantial boost for their fiscal autonomy while providing fiscal resources.

This combination of expenditure reallocation (1% of GDP) and additional tax effort focused on personal income, VAT, and local government revenues (4.0% of GDP) can finance the additional 4% of GDP required to fund critical social programs, while also leaving a surplus of 1% of GDP for additional investment in infrastructure.

This fiscal policy package can be a powerful instrument for improving income distribution as the incidence of this tax and expenditure package is likely to be progressive. In addition to a redistributive fiscal policy, the government can also help improve income distribution through better governance.

Implementation of the 8FYP Strategy for Redistributive Fiscal Policies in the FY2023 Budget

The advent of Covid-19 disrupted the implementation of the 8FYP redistributive fiscal policies. The main focus has been on economic recovery, although some additional spending was also provided for social protection to support the poor and low- income group.

Given the solid recovery of economic growth, greater policy attention could be given to social spending in the national budget of FY2022-23. Attention could also shift to improving the tax system of Bangladesh both to mobilise greater tax revenues as a share of GDP and to increase reliance on progressive personal income taxation.

Proposed Spending Reforms for FY2023 Budget

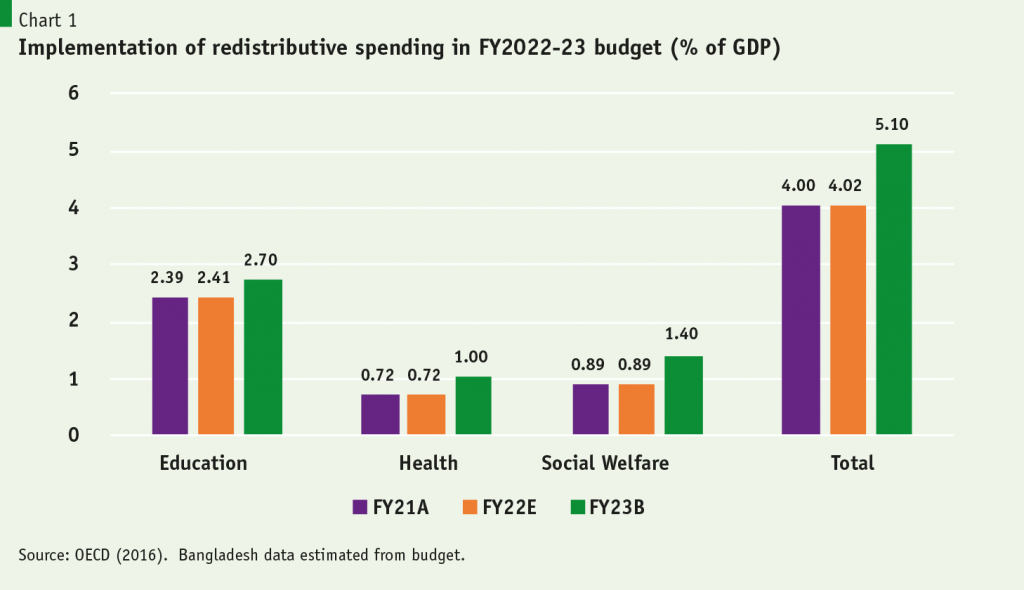

Since tax reforms will take time, immediate attention could be given in the FY2022-23 budget to significantly increase social spending in Bangladesh, as illustrated in Chart 1. Actual spending in FY2021 (FY21A) as a percentage of GDP on education, health, and social protection (excluding civil service pension) was 2.39%, 0.72% and 0.89% respectively, yielding a total social sector spending of 4.00% of GDP.

There was an effort to increase this spending in the FY2022 Budget. But actual spending in the first half of FY2022 suggests that as in FY2021, actual spending will be significantly lower. Applying the ratio of FY2021 actual to budget spending to FY2022 Budget, estimated allocations suggest that actual social sector spending on education, health, and social protection in FY2022 (FY22E) will likely remain unchanged over the FY2021 actual level.

The suggested strategy for the upcoming Budget (FY23B) is to make a major increase in all three sectors, with the largest increase in social protection. Thus, it is proposed to increase education spending as a share of GDP from 2.41% in FY2022 to 2.71%; health spending from 0.72% to 1.0%; and spending on social protection (excluding civil service pension) from 0.89% in FY2022 to 1.4%. These proposed increases amount to a total of 1% of GDP additional spending on social sector. These budget allocations will need to be protected from implementation shortfalls. Attention should also be given to improving the delivery of social programs to ensure that these are best targeted to the poor, the vulnerable and the low-income group.

Towards a Universal Health Care System

A particularly important spending reform that may help reduce income inequality will be to initiate the implementation of a universal health care (UHC) program, as has been done in several Asian countries, and more recently in the South Asian countries of Pakistan and India. The UHC is now embedded as a goal in the SDG. The SDG target 3.8 says: “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

In Bangladesh, the focus of public healthcare spending has been basically to contain and where possible eliminate the incidence of mass communicable diseases and provide basic rural healthcare for the poor.

There are also public curative healthcare facilities (hospitals) at the district level and more advanced hospitals at the national level. Much of the curative healthcare is provided through private clinics and hospitals. Out-of-pocket healthcare spending has been growing over the years and is estimated at around 4% of GDP.

The limited public spending (0.7% of GDP) has constrained the government’s ability to provide good health care in public facilities, forcing even the very poor to seek medical services from private providers. Private healthcare is expensive and successive Household Income and Expenditure Surveys (HIES) show that health shocks are a major source of vulnerability of the poor in both urban and rural areas.

Bangladesh aspires to attain Upper Middle-Income Country (UMIC) status by FY2031. Yet, the healthcare is highly inadequate to meet the needs of an UMIC. Apart from Thailand and Malaysia, many other UMICs like Argentina, Brazil and Mexico have adopted a UHC. India, a Low Middle-Income Country (LMIC), adopted an UHC in 2018 through the “Ayushman Bharat” scheme. Pakistan in January 2022 introduced a UHC scheme known as ‘Naya Pakistani Quami Sehat Card” with initial application in selected Provinces and Federally Administered Areas.

The main challenge for adopting UHC is the fiscal cost. Experience of countries that have adopted UHC shows that a range of programs can be adopted to implement UHC that is a mix of public and private financing based on income and public preferences. The private funding usually happens through employment-based health insurance co-financing. The health insurance is provided by private suppliers and is open to all including those who are self-employed. The public support can be provided either as subsidised access to private insurance or as subsidised access to a publicly managed health insurance plan such as the Medicare in USA.

There is no one size fit-all solution to medical insurance or approach to UHC. Bangladesh can learn from good practice examples of countries, especially from the UHC system in Thailand and Malaysia.