Using Padma Bridge to deal with regional inequality

By

With the completion of the Padma Bridge, Bangladesh has reached one of its milestones by connecting the relatively backward southwest region to Dhaka and the rest of the country. The bridge has far-reaching implications through a variety of direct and indirect effects. The benefits arising from this connectivity can play a pivotal role in addressing regional inequality. For this to happen, proactive measures must be taken through a big investment push, formation of cluster economies, development and making productive use of special economic zones (SEZs), promotion of the tourism industry, etc.

The benefits of the Padma Bridge and its importance in the context of regional disparity

The contribution of the Padma Bridge to the growth of the country’s GDP is estimated to be more than 1%. According to a World Bank report, about 30 million people in Bangladesh will directly benefit from the Padma Bridge as a result of increased connectivity. The direct immediate benefits come in the form of reduced time and cost of transporting goods and passengers as the distance by road between Dhaka and most of the south-western districts will be reduced by at least 100 km.

In an analysis using a model of traffic flow, the estimated total benefit over a three-decade period based on saved vehicle operation and travel time cost alone stood at TK 1,295,840 million ($13,658 million). The distance between Dhaka and any of the 21 districts would reduce by 2 hours on average.

The bridge will reduce the distance between Mongla and Dhaka by over 100 kilometers, making Mongla port closer to Dhaka than Chittagong port. There will also be a direct linkage between the Payra and Mongla ports. Using the bridge, Bangladesh will also be connected to the Trans Asian Highway and Trans Asian Railway, and this, in turn, is expected to open up new avenues of intra-regional trade involving both South and East Asian countries.

The bridge holds further profound significance for the southwestern region of Bangladesh. In terms of economic activities and employment generation, this region has lagged due to inherently being in a disadvantaged location. The Padma kept the south-western districts, including the third-largest city, Khulna, isolated from the major growth centres of Dhaka and Chittagong.

The river acted as a major barrier in transporting goods and passengers from that region to other parts. The average waiting time at ferry points was estimated to be around 2 hours for passenger cars and buses and a staggering 10 hours waiting time for trucks. The situation used to get even more severe under extreme weather conditions when the river becomes impossible to navigate. The trade and agriculture of this region was particularly a victim of this disrupted connectivity giving rise to huge economic loss in the form of lost hours and wastage.

Almost 30% of the total population of Bangladesh lives in the southwest in a total area spanning over 43,954 sq km to host the third-largest city of the country, Khulna, and 2 ports, Mongla and Payra. Yet, this region lags in terms of industrialisation. Due to inconvenience in transportation, the cost of doing business has been very for this region, limiting economic activities.

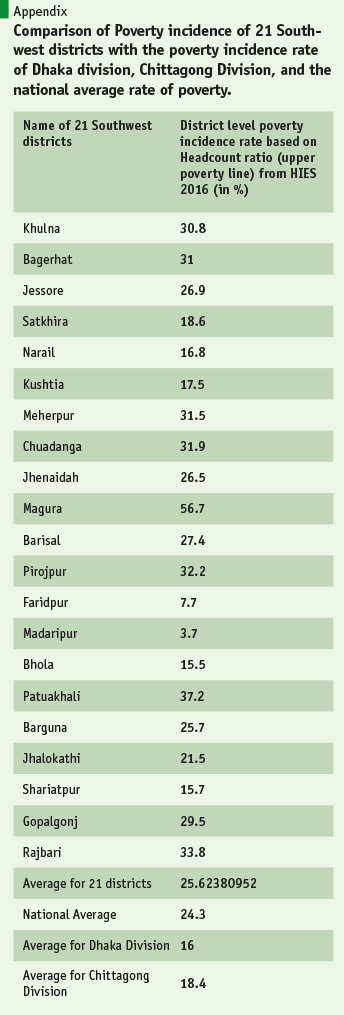

According to district-level poverty rate data from HIES 2016 based on the Head Count ratio (upper poverty line), it could be seen that the poverty occurrence in these 21 districts is 1.3 % higher than the national average, 9.6 % higher than the Dhaka division, and 7.2 % higher than Chittagong division. It is evident from these figures that cumulated over time; the geographical disadvantage has been translated into economic repercussions for the whole region.

It is now widely expected that the bridge will help address the inherent disadvantage. According to a study by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the southwest regional GDP is projected to rise by 3.5% due to the bridge. The region is expected to grow through rapid industrialisation and urbanisation.

There is a general belief that the bridge would lead to decentralisation and help in addressing the regional disparity. The benefit of infrastructural development, like bridges, in the growth of the regional economy, is well acknowledged. Countries like China and Indonesia provide evidence of the positive effects of bridges like Hangzhou Bay Bridge and Suramadu Bridge on the development of less advanced regions in the past. However, the bridge itself may not be sufficient to bring about all the desired changes.

The theory of the growth of large cities and why improved connectivity alone may not be sufficient to address the greater issue of regional disparity

To understand why there is a need for additional measures to reap the maximum benefit of constructing the bridge, it is important to explore the growth dynamics of a region. Understanding why certain regions grow more than others has always been a major concern for economists and policymakers.

There are important theoretical insights in exploring the growth dynamics of large cities. In the 1960s and 1970s, Nobel Laureate economist Gunnar Myrdal postulated that economic development in a region is often driven by some inherent locational advantage. Based on that advantage, a region goes through further transformations attracting different economic agents like buyers, sellers, and workers to concentrate in that location.

Later on, another Nobel Laureate economist, Paul Krugman, provided further insight into this matter. According to him, the emergence of big cities is largely dependent on the effects of agglomeration. Agglomeration economies refer to the benefits that firms enjoy by locating near each other. It results in a decline in the cost of production because the firms can benefit from externalities and economies of scale which arises from the improved backward and forward linkages.

The benefits come in the form of shared knowledge, technologies, services, specialised labour, factor prices, and infrastructural support. Based on these benefits, firms decide to concentrate their production in a particular geographic location. Those locations are usually places that are close to customers and markets. Moreover, many other firms related to them also grow simultaneously. This helps tremendously in reducing the transportation cost as suppliers and distributors are located nearby. When more firms start locating in a region, a diversified pool of labour force is also attracted to that place. This large influx of labour in search of varied working opportunities helps in increasing the market base as they are also an important section of the consumer group.

Overall, these lead to further opportunities for firms, as the increased customer base has specialised needs for a wide variety of products. Based on these developments, government and private investors invest further into new infrastructures and businesses. In this way, the system keeps on reinforcing the regional economy, leading to rapid urbanisation and the formation of vibrant, large-scale agglomeration economies.

Once such an agglomeration economy is formed, it is very difficult to attract businesses elsewhere other than these large cities. Neither the workers nor the businesses want to move out of such established cities and give up the facilities like easy access to a large and varied market, supplies and utilities, administrative and infrastructural supports etc. Special incentives are required to move them from the growth centres.

Over the past decades, as an outcome of industrialisation and urbanisation, Bangladesh has followed a non-uniform pattern of growth across the country. Most of the economic activities are concentrated in the two megacities, Dhaka and Chittagong. Investors have heavily invested in these two large cities and their outskirts. A huge number of workers from all over the country have moved into these cities. Their consumption demand has further attracted firms to locate in that vicinity.

Cities have expanded rapidly as a result of the benefits of economies of scale. Nearby districts which have easy access to these cities also grew as they became an important part of the supply chain. On the other hand, districts further away from Dhaka, e.g., the southwestern region, have struggled to generate agglomeration economies while their resources are being pulled into the already established growth centres. The connectivity challenges have fuelled regional disparities, particularly in southwestern districts.

The Padma Bridge would improve the connectivity of the southwestern region and remove some of the barriers that hindered economic development in the past. However, only having a bridge to ensure connectivity does not necessarily mean the growth of a region.

The general perception is that the bridge would benefit the southwestern region but looking through the lens of Krugman’s theory, it is also a possibility that the pull factor of the already established growth centres like Dhaka will be reinforced by the newly constructed bridge. With increased connectivity, it would be easy for people and businesses to move toward the growth centres. One immediate impact of the bridge could be such that people from that region would more vigorously explore working opportunities in Dhaka. Many firms might also think of relocating with the hope of serving a larger market.

As explained by Krugman, the occurrence of such incidents is very likely and has happened in many places in the past. To overcome the pull factor of the existing growth centres, the southwest region needs to offer incentives for locating and remaining in the region that should outweigh the benefits that investors currently enjoy at the growth centres.

That is, to eliminate the likelihood of the reverse effect of the expected net direction of resource flow and to help address the regional disparity by utilising the potential of the bridge, there is a need for taking certain proactive measures to boost the regional economy of south-west districts.

Proactive measures are needed to exploit the opportunities created by Padma Bridge to address regional disparity

A. Investment push to grow a broader economic base in the southwest region

An overarching policy strategy should constitute a big investment push toward the southwest region. Evidence from China shows that investment in public infrastructure can be both an explanation for regional inequality and thus part of a strategy for containing rising regional inequality. The bridge is a significant public investment, which must be complemented by other local projects. The land is already relatively less expensive in south-western districts but that may not be enough for developing mass agglomeration economies.

Along with the public sector investment drive, offering fiscal and financial incentives for private sector investment decisions should be very helpful. There are certain areas, for instance, travel and tourism, where public infrastructural development and private investment should go hand-in-hand. This should be one initial area of focus given that the tourism potential of the region has remained much less exploited due to erstwhile difficulties associated with transportation connectivity. Along with it, by providing improved supplies of natural gas power, and high-speed internet, the profitability of private sector enterprises can be enhanced. The investment push can be exerted through many different channels.

B. Promoting cluster economies

Helping build manufacturing clusters can be key to unleashing the growth potential of the region. Food/Agro-processing, jute processing, fish farming, leather, light engineering, or any other SME clusters could be viable options. Cluster economies refer to the concentration of interconnected firms and their supporting activities in a particular geographic area.

The formation of cluster economies is inherently spontaneous, but nowadays many clusters are also formed through government interventions. The relevant industries enjoy a lot of benefits from locating in a cluster. Government can help to boost up the existing clusters and create new ones by providing different incentives and organisational support.

According to the information given by Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation, around 500-1000 factories of different categories are likely to be established in areas surrounding Barisal alone after the construction of Padma Bridge. There had been also a sharp spike in demand for land beside the road at both ends of the bridge and their prices have increased.

All this signals that due to the bridge, the region is finally gaining attention from the local investors. But this will have to be consolidated and strengthened further and the best way the growth momentum can be sustained is through the development of certain manufacturing clusters. Support in the form of subsidies, tax exemptions, technical and administrative support, training, etc. can catalyse the formation of clusters. The region has an inherent comparative advantage in agricultural production. This can be utilised further by developing agri-based cluster economies to benefit local businesses. Several such clusters can then lead the way for the formation of an agglomeration economy in this region.

C. Investing in SEZs

Another related important tool is the development of selective Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Though there are ambiguous views on the effectiveness of SEZs as a tool for addressing regional disparity, SEZs in China has been particularly successful in terms of making an export-led growth strategy work and helping various regions to flourish. Similarly, Thailand and Vietnam also used SEZs to counteract the concentration of people and economic activity in the megacities of Bangkok and Ho Chi Minh City. The SEZs have been explicitly used as a tool to help stimulate backward regions.

Bangladesh had an elaborate plan for establishing 100 SEZs across the country and developmental activities in many of these zones are underway. However, despite the allocation of space for SEZs in the southwest, there has been apprehension about their ability to attract potential investors largely due to the transportation and energy constraints inflicted by the Padma. After the construction of the bridge, mobilising investments—from both foreign and domestic sources—should now have much better prospects provided that the enabling environment and complementary services are made available in the region.

Currently, there are plans for 17 SEZs in the southwestern region and some of those are in the advanced stage of completion. The reduction in transportation time and cost from the growth centre will surely benefit the producers and supplies located in these SEZs. And the access to interregional connectivity through the Trans Asian Highway and Railway can further create new avenues of trade with India and many East Asian countries including China. The decrease in distance of Mongla port from Dhaka, and the direct link between Mongla and Payra port, can incentivise export-oriented companies and foreign investors to consider the southwestern region for their production. However, the potential will remain un-/under-utilised if proactive concerted measures are not considered.

Based on the principles of agglomeration economies, the government can take an initiative to prioritise a few selective SEZs in the region and invest adequately to transform those into growth centres. The selected SEZs should be supported with all other necessary services in the form of institutional and financial support to enable businesses to grow. Through appropriate and scaled-up vocational and technical training programs in the region, the government can also help the firms have access to a readily available skilled workforce. That can further act as an incentive for the investors as the cost of labour and land would be cheaper in this region compared to other growth centres.

D. Attracting FDI

It is extremely important to be proactive in mobilizing foreign direct investment, especially for exports. Given the geographical location of the world’s two largest and most dynamic economies, India and China, there are tremendous opportunities for Bangladesh to expand export to and attract investments from them. China has promised foreign direct investment worth tens of billions of dollars under various projects while Indian investors have already been allocated two SEZs: one on Mongla and the other in Kushtia. One proactive initiative will be to work with India to operationalise the two SEZs and the other will be to channel some of the Chinese investments into the southwest region. Along with these, further investment opportunities should be explored.

E. Reviving the Tourism industry

Padma Bridge presents enormous opportunities for revving up the tourism activities in the southwest region through proper planning and implementation. If the environment could be made conducive for travellers, the tourism industry can evolve in this region based on such attractions as the Sundarbans, Kuakata, Bhola, small islands (char lands), etc. Like the Sabrang Tourism Park in Cox’s bazaar, a few similar tourism parks should be developed in the southwest region. The reduction in travelling time through Benapol is also expected to have a positive impact on the movement of tourists across the border and for the travellers to and from Kolkata, West Bengal in India, and the southwestern districts can emerge as important transit holiday points.

F. Formation of an economic corridor

The bridge is expected to enhance inter-regional connectivity and strengthen the different modes of transport linkages. Utilizing these facilities provided by Padma Bridge, an effective medium to long-term strategy will be to turn this region into an international economic corridor. Economic corridors are an integrated system of roads, rails, ports, and other infrastructural projects that connect various regions and countries. Through the interlinked centres of production, manufacturing hubs, industrial clusters, and economic zones, as well as centres of demand, such as capitals and major cities, these corridors act as gateways to the concerned subregions for regional and international trade. The bridge paves the way for promoting sub-regional economic integration in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Nepal and for a more extended scheme involving South-East Asian countries. In this respect, the policymakers should closely study the implementation of the Greater Mekong Subregion comprising the six countries of Cambodia, China (specifically, Yunnan province and the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam to derive any helpful lessons that can magnify the impact of Padma Bridge.

Conclusion

There is no denying that regional infrastructural development projects can promote inclusive growth. However, the benefits of infrastructure do not always translate into economic development automatically especially when established agglomeration economies tend to cause certain disadvantages for the lagging or backward regions. The greater success of the Padma bridge, in the long run, will largely depend on transforming south-western Bangladesh into a major national and regional growth centre. If the bridge and improved connectivity are not complemented with proactive policies to boost the regional economy, the so-called ‘backwash effect’, where people and resources move towards the prominent urban centres as cannot be prevented and actually can get aggravated as a result of the increased connectivity. Padma bridge has definitely opened up multiple windows of opportunities for the southwestern region. Only through prudent and focused development strategies, can the Padma Bridge play a critical role in addressing regional disparities within Bangladesh.