Propelling Development Through a Strengthened Taxation System

By

Domestic Resource Mobilisation in Bangladesh: The Context

Over the past decades prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Bangladesh achieved commendable socio-economic development with sustained economic growth, averaging 5.6% per annum since 1990 and 6.7% during 2010—2019; and brisk poverty reduction, as reflected in the proportion of the population, living below the poverty line, falling from more than 50% in the 1990s to just 20.5% in 2019. Compared to many other countries at a similar stage of development, Bangladesh achieved faster progress in various social and human development indicators such as health, demographic and gender equality outcomes. In 2015, Bangladesh moved from a low-income to a lower-middle-income country as per the World Bank’s classification of global economies. Even amid Covid-19 disruptions, it remained resilient by posting positive economic growth and securing the qualification for graduating from the group of the United Nations-designated Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in 2026. The policymakers in the country have set their sights on other aspirational targets, such as achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and becoming an upper-middle-income country by 2031.

The ongoing development transitions would require catering to the ever-rising demand for infrastructure including energy, education, health services along with their improved quality, social protection support, skill development for labour market opportunities, etc. It is in this context, that the extremely limited public spending capacity, within which the government of Bangladesh must manage the demand for resources, has become a major concern in fostering future socio-economic progress.

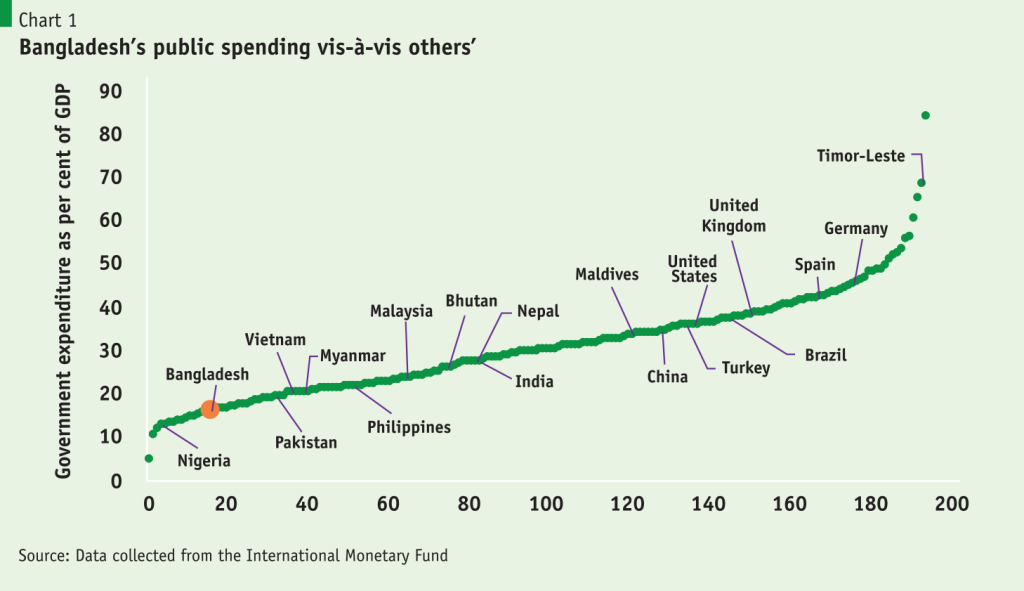

It is in this context, that the extremely limited public spending capacity, within which the government of Bangladesh must manage the demand for resources, has become a major concern in fostering future socio-economic progress.

• Bangladesh’s current public expenditure, about 15% of GDP, is much smaller than that of many other comparator countries such as Cambodia (24%), India (30%), Nepal (27%), Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines (25% for each) and Vietnam (22%).

• The low public spending is a direct outcome of a weak revenue-generating capacity. The tax-GDP ratio in Bangladesh is one of the lowest amongst global economies (about 8% of GDP).

Why is Domestic Resource Mobilisation more important now than ever?

First and foremost, given the low level of spending, the government’s fiscal space has become severely constrained to allocate additional resources to health, education and social protection.

• Based on a wide range of evidence and comparisons across countries, it is generally held that government spending on health should be at least 5% of GDP. In Bangladesh, it is just 0.7%, which according to the 8th Five-Year Plan (FYP), should be raised to 2% by 2025.

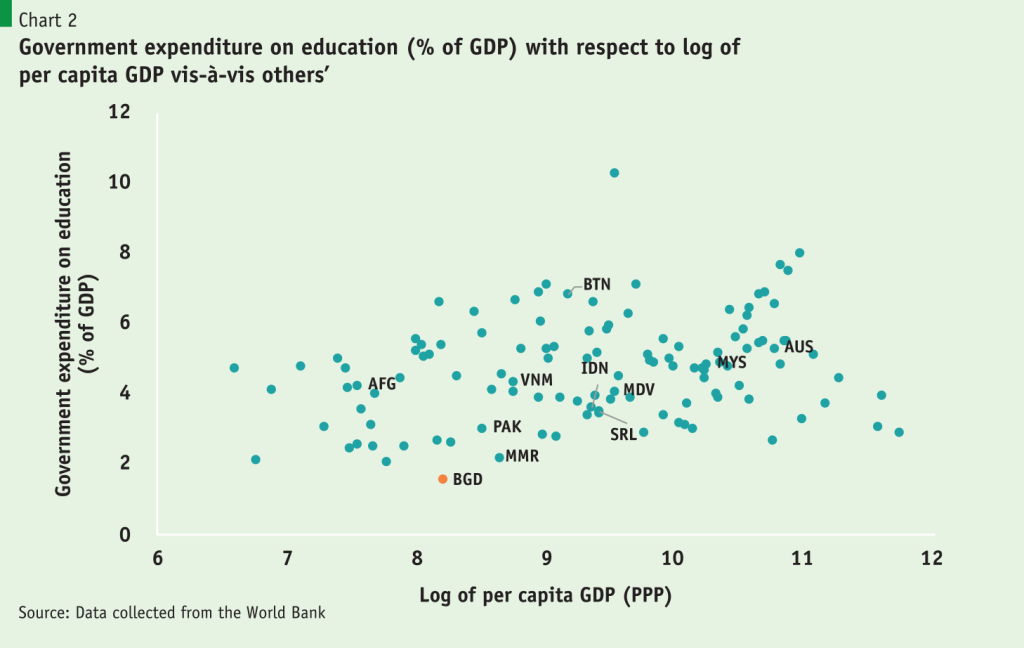

• The UNESCO’s Education 2030 Framework for Action stipulates a target of at least 4% of GDP as public spending in education. For Bangladesh, the corresponding spending is 2% and 8th FYP has proposed to increase it to 3% by 2025. With the current level of domestic revenue collection, the 8th FYP targets on health and education spending will not be materialised.

• The lack of financial resources means important social protection schemes such as allowances for elderly people, widows and destitute women, mothers and child benefit programmes etc., operate only at a far less than the comprehensive coverage that the National Social Security Strategy adopted in 2015 envisaged to achieve. Allowances provided to current beneficiaries have not been possible to increase for several years, despite the rise in price levels.

Therefore, one important issue Bangladesh should face is that sustained underinvestment in health, education and social protection may hamper human capital development, under- mining future socio-economic progress and productivity gains. Moreover, inadequate public investment in these areas can worsen socio-economic inequality.

Second, Bangladesh’s development transformation from a weak economic state to a fast-growing middle-income nation has an adverse impact on accessing external development support on concessional terms necessitating the need for enhanced Domestic Resource Mobilisation (DRM) efforts. Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) i.e. grants or loans with concessional terms, received both bilaterally and multilaterally, which has been an important source of development financing, is already being offered with higher interest rates and/or at less concessional terms because the country is transitioning from the group of low income to lower-middle income countries. After LDC graduation, accessing some of the LDC-specific funds will get discontinued or will be limited to only a few years.

Third, the ongoing unfavourable macroeconomic developments provide a renewed emphasis on relying more on domestic resources. Bangladesh, like many other countries, faces global economic shocks resulting in commodity and fuel price hikes. This has been accompanied by a surge in imports in the post-Covid economic recovery period, which contributed further to widening the balance of payments deficits, thereby putting pressure on foreign reserves and triggering a significant depreciation of taka.

…the ongoing unfavourable macroeconomic developments provide a renewed emphasis on relying more on domestic resources. Bangladesh, like many other countries, faces global economic shocks resulting in commodity and fuel price hikes.

• Although the overall external debt stock remained sustainable as a proportion to GDP (less than 25%), it recently grew faster, from less than USD 40 billion in FY2015 to about USD 96 billion in FY2022. The yearly public sector external debt service charges will rise from currently around USD 3 billion to USD 5.2 billion in 2030. If the private sector charges are added, the same will rise further to more than USD 8 billion.

• As the price of USD in terms of BDT has risen by more than 20% over the past few months, the government and private sectors will have to find considerably higher budgetary resources (in taka) to service foreign debt. With an already very low level of tax-GDP ratio, the increased provisioning for loan repayment will put further pressure on fiscal space.

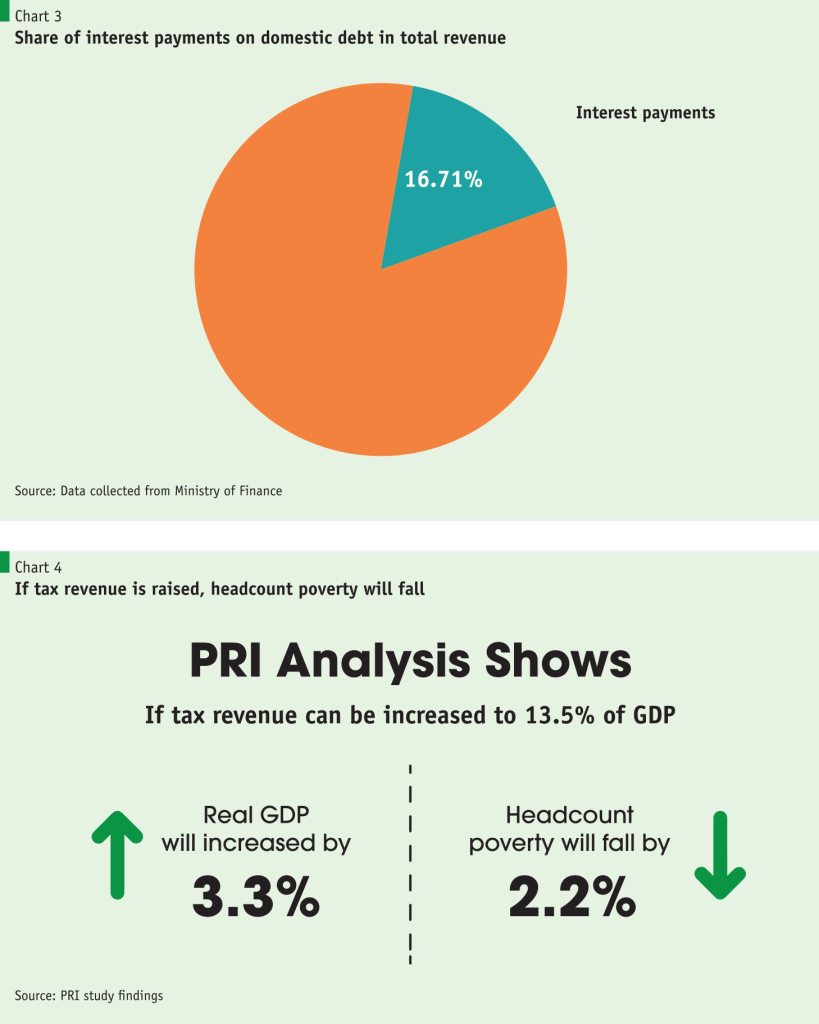

Finally, persistent fiscal deficits have resulted in the ballooning of government borrowing from domestic sources with interest rates much higher than that of external financing and requiring increasingly more resources to be found from domestic sources.

• Consequently, interest payments on domestic borrowing eat into the already constrained fiscal space. Interest payments on domestic debt is currently (FY2022) as high as 16.71% of all government revenue and 10.95% of total public spending.

• The government’s Annual Development Plan (ADP) budget is currently fully provided for by deficit financing, involving interest payments and debt servicing charges.

Therefore, development spending in Bangladesh is more expensive than necessary .

Tremendous opportunities for promoting development and tackling inequality through improved domestic taxation efforts

There is mounting evidence of a robust relationship between public spending and socioeconomic development. This is reflected in a steady rise in public spending over the past 150 years in almost all global economies. In OECD countries, spending is now at historically high levels of nearly 40% of GDP. Using historical data from 139 countries and rigorous econometric analysis, a 2016 IMF study finds that a tax-GDP ratio of 15% can serve as a ‘tipping point’ for shifting countries to a new equilibrium state of higher economic growth.

In Bangladesh as well, a broad-based consensus exists that enhanced DRM is critical for building upon the socio-economic progress that has been made so far. In this regard, the 8th FYP provides a realistic roadmap for raising the tax-GDP ratio from the current level (of around 8%) to 12.3% in FY2025 and the tax plus non-tax revenue-GDP ratio to 14.1%.

Despite the progress towards realising those targets being slower than expected, there exists an immense potential to boost the DRM drive.

• PRI research shows that if the top 10% of households in the country are subject to income tax rates of 10%—15%, the income tax-GDP ratio should rise from the current 1% of GDP to 3.8%—5.7%.

The government has taken significant initiatives to enforce tax returns by the people who were issued with taxpayer identification numbers (TIN). Personal income tax return submission has been just about one-third of the people with TIN (around 7.5 million individuals). Along with this, there are efforts to expand the tax net. Recently, in a high-level public consultation, the National Board of Revenue (NBR) set out a target to increase the share of direct tax to 70% of the total revenue (from the current level of around 30%). This is a welcoming initiative, as the increasing reliance on direct taxation can help tackle the growing inequality.

• Findings from an upcoming PRI research show that raising an additional tax-GDP ratio of 5-percentage-points from direct taxes and spending the same on social protection would increase the overall GDP by 3.3%, reduce the headcount poverty by 2.2-percentage-points and lower the income gini coefficient—a popularly used measure of income inequality—from the currently 0.48 to 0.46.

Raising revenue from domestic sources to support economic development and address inequality can be materialised through renewed revenue mobilisation efforts complemented by critical tax policy, administrative reforms and relevant institutional capacity-building initiatives. The needed reforms have long been discussed, and the 8th FYP provides an apposite outline. The current global economic turmoil triggering development challenges across the world should also be seen as an opportunity for a country like Bangladesh, for which improving the government’s fiscal situation has long been overdue and is widely regarded to be achievable given the extremely low level of current tax effort and should constitute a priority given the country’s ongoing economic transformation and further development aspirations.

Raising revenue from domestic sources to support economic development and address inequality can be materialised through renewed revenue mobilisation efforts complemented by critical tax policy, administrative reforms and relevant institutional capacity-building initiatives.

The importance of strengthening DRM cannot be overemphasised in propelling the development transition that Bangladesh is passing through. This is also reflected in the government’s policy statements and development strategies.