Instituting Greater Realism in Tax Revenue Targets

By

Bangladesh seems to have adopted a tradition to set unrealistic tax revenue targets in the National Budget and then underperform, knowing well that the tax targets are not achievable. This is baffling and unfortunate. Baffling because the rationale for doing so is not clear. Unfortunate because it undermines the credibility of the budget. It is also surprising that the National Parliament has not investigated this matter and directed government officials to do away with this practice or otherwise be held accountable for under-performance.

Some deviation from the target is always possible owing to a variety of factors, including adverse external developments, unforeseen domestic disruptions, and unanticipated implementation capacity constraints. But the deviations in tax revenue are large, recurring, and predictable. I hope the chairman of the NBR, the Finance Secretary, and the Finance Minister will look into this matter seriously, debate the value of this practice, and help set up a more transparent and realistic budget process. This will better serve the country and improve confidence in the budget-making process.

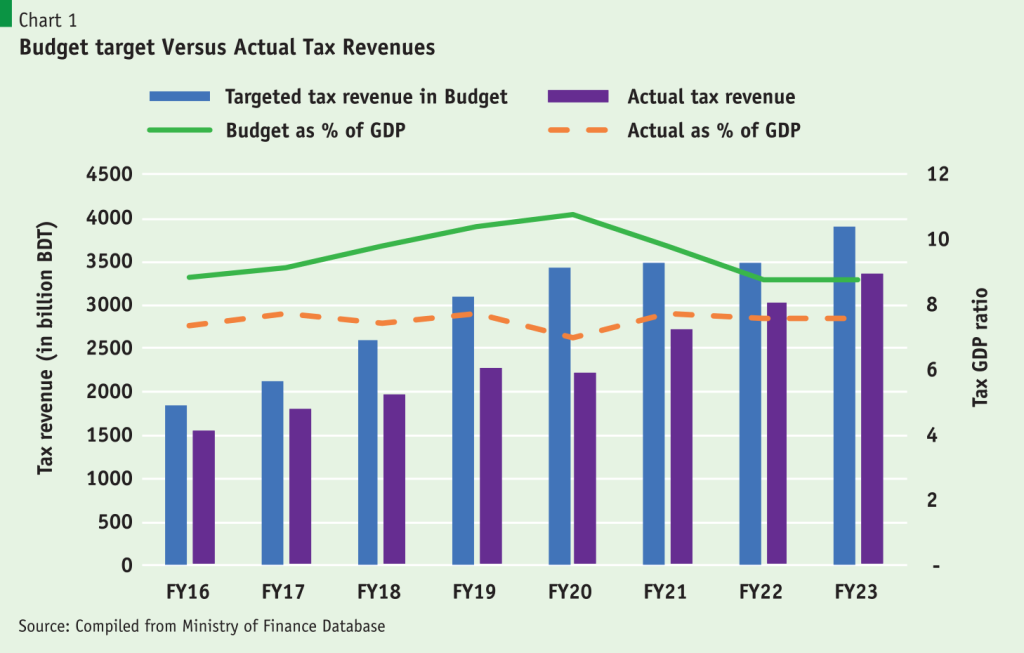

The magnitude of this unrealism in budget making is illustrated in Chart 1. Several results emerge from the chart. First, the actual tax/GDP ratio has remained virtually flat at around 7–8% over the past 7 years. This is very distressful in an environment where public spending needs have expanded progressively. Second, the gap between the budget target and the actual tax collection is large. The percentage gap between budget and actual revenue collection has ranged from a peak of 35% in FY2020 to 13% in FY2022. In absolute terms, the tax revenue gap was BDT 1.3 trillion in FY2020, which fell to BDT 484 billion in FY2022 and then climbed again to BDT 548 billion in FY2023. Third, the gap has been consistently above 10% over the past 10 years, suggesting that setting unrealistic tax targets has become a standard practice in budget making.

The non-transparency of budget making is further illustrated by the experience of the FY2024 budget that was approved by Parliament at the end of June 2023. Amazingly, the FY2024 budget kept the original target of BDT 3880 billion for tax revenue in FY2023 as the revised target and used it as the base for projecting the tax target for FY2024, even when the Ministry of Finance had actual revenue data for the first 10 months of FY2023 (July–April) that showed a huge gap in revenue collection over the budget. It then used this highly inflated and unrealistic tax base for FY2023 to project a massive tax revenue collection of BDT 4500 billion for FY2024. Since actual tax revenue collection in FY2023 was BDT 3332 billion, this suggests a ridiculous revenue target for FY2024, which is some 35% higher than in FY2023. When the average revenue growth over the past 8 years is only 11.8%, how can tax revenues jump to 35% in FY2024 in an environment of continued macroeconomic instability, falling GDP growth, import controls, and lower export growth?

When the average revenue growth over the past 8 years is only 11.8%, how can tax revenues jump to 35% in FY2024 in an environment of continued macroeconomic instability, falling GDP growth, import controls, and lower export growth?

Surprisingly, neither the cabinet nor the Parliament debated this matter to check for realism in the revenue collection target. It is true that the FY2024 budget incorporates some tax revenue measures. But similar measures were announced in every budget. Trying to mobilise an additional 2% of GDP in FY2024 is a herculean tax, which is highly improbable even with a major overhaul of the tax system that is not on the cards.

This type of wishful and non-transparent revenue target is harmful because the expenditure targets set with such inflated revenue targets are also misleading. Over 50% of government spending is a fixed-commitment type that cannot be adjusted to reflect revenue shortfalls. These include civil service salaries, pensions, the interest cost of public debt, supplies and materials, defence and security spending, and transfers to local governments. The remaining 45–50% of the budget is then subject to expenditure cuts to adjust to the realities of revenue.

This type of wishful and non-transparent revenue target is harmful because the expenditure targets set with such inflated revenue targets are also misleading.

The budgeted fiscal deficit is already large, and there is little room to wiggle, but the unrealism in revenue setting could also trigger a further increase in the budget deficit. The existing budget deficit is mostly financed through borrowings from the Bangladesh Bank (money creation), which is hurting the already worrisome near-double-digit rate of inflation. A further increase in the budget deficit financed through money creation would further aggravate inflation.

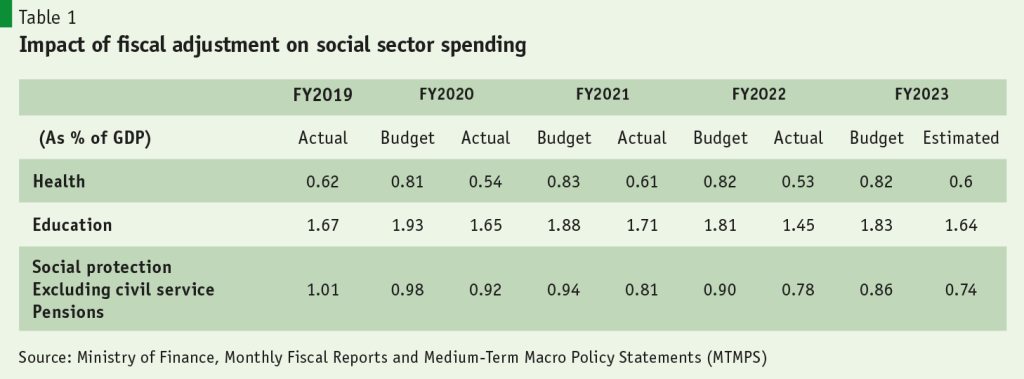

It is most likely that the government will try to adjust to lower tax revenues by instituting deeper cuts in development spending and social safety net transfers, as in the past. These levels of spending, especially for health, education, water supply, irrigation, flood control, and social protection, are already very low. Further cutbacks will constrain the recovery of growth and human development. Additionally, income inequality is rising in Bangladesh, and the government’s ability to lower income inequality by implementing a programme of redistributive fiscal policy, as envisaged in the Eighth Five Year Plan (8FYP), will suffer.

The impact of this expenditure policy on public spending on health, education, and social protection is illustrated in Table 1 below. Spending on these high-priority items has been low in recent years. Recognising this, the 8FYP sought to increase public spending on health from 0.7% of GDP in FY2019 to 2.0% of GDP in FY2025; education spending from 2.0% of GDP in FY2019 to 3.0% of GDP by FY2025; and spending on social protection (excluding civil service pension) from 1.2% of GDP in FY2019 to 2.0% of GDP by FY2025. Notwithstanding the 8FYP’s intentions, spending as a share of GDP on these priority areas has declined further. The annual budgets made efforts to get some modest increases in spending on these high-priority areas. But even these modest budgeted increases were not feasible due to revenue constraints. Thus, in FY2023, Bangladesh spent a mere 0.5% of GDP on healthcare, 1.5% of GDP on education, and 0.8% of GDP on social protection (excluding civil service pensions). As is obvious, these spending outcomes are far removed from the targets set by the 8FYP.

The only way out is to seriously rethink the government’s current ineffective tax policy and institute major reforms as identified in the Medium-Term Fiscal Framework of the 8FYP and the Perspective Plan 2041 (PP2041). Reforms of state-owned financial and non-financial enterprises will also help increase government revenues substantially. These reforms are all well documented and known to the government. Finally, a policy of fiscal decentralisation with greater fiscal and administrative responsibilities devolved to local governments will contribute to the domestic resource mobilisation required to finance higher public development spending.

The 8FYP and PP2041 have developed these revenue mobilisation themes quite elaborately. The government needs to focus attention on these reforms to get some real action, rather than set unrealistic revenue targets based on fiction.