Spurring the Growth of Micro and Small Enterprises Through Innovative Financial Solutions

By

Bangladesh successfully transited from low-income to lower-middle income country in 2015. Since then, rapid GDP growth averaging 7.6% per year brought Bangladesh per capita gross national income (GNI) to around the USD 2000 mark in 2019. This growth acceleration was paused by the advent of Covid-19 in March 2020. Nevertheless, economic growth remained positive in 2020 and there are welcome indications of economic recovery in 2021. However, even before Covid-19, there were worrisome signs of slowdown in the growth of employment in the organized sector, especially manufacturing. Covid-19 has further hurt employment growth in both organized and informal activities, and has also slowed employment prospects in the overseas markets. Overall, job creation has emerged as the foremost development challenge facing Bangladesh today.

Owing to the ongoing economic transformation, where the rapid GDP growth is led by the manufacturing sector and organized services, the GDP and employment shares of manufacturing and organized services have increased and exports of manufactured goods have surged. Yet, an estimated 79% of the workforce is engaged in low-income agriculture and informal service activities, while manufacturing exports are heavily concentrated in one-product group – Readymade Garments (RMG). Following solid growth in employment during 1995-2010, employment in RMG has stagnated at around 4 million workers.

International experience with micro and small and enterprises (MSEs) suggests that the sector can be an important driver of employment, investment, exports and economic growth. Evidence from Bangladesh shows that MSEs are the main source of non-farm employment and have played a very important role in poverty reduction. Yet, they lack dynamism and are performing much below potential. There are many constraints that adversely affect the growth of these enterprises. One binding constraint is the access to institutional finance. The microcredit revolution has sharply increased the credit access of microenterprises through the lightly-regulated micro-financial institutions (MFIs). Similarly, the adoption of supportive credit policies by the Bangladesh Bank (BB) in 2011 has significantly increased the supply of bank credit to small and medium enterprises. Nevertheless, the overall financing constraint for MSEs remains substantial.

The microenterprises face borrowing rate of 23-24% from MFIs, whereas the interest rate on banking sector credit has been capped at a mere 9%. Even at the higher MFI rate, there is a significant financing gap for microenterprises. When the 100% plus higher interest rate charged by the MFIs over the banking sector lending rate is considered, the financing gap is substantially larger. Available evidence shows that despite progress, the financing gap for small enterprises is also huge. For example, only 20% of the small enterprises have access to banking credit. On the other hand, data from the Bangladesh Bank shows that the medium enterprises are much better served by the banking sector and may not face a credit constraint.

Research findings suggests that several factors contribute to the present situation regarding the MSE financing constraint.

First, a strategic view and a road map for the development of the MSE sector are missing. As a result, multiple definitions of MSEs have prevailed. There is no baseline data on MSEs, which prevents a good assessment of its performance and a solid diagnostic study about the underlying constraints. The absence of a monitoring and evaluation framework has meant that there is no systematic assessment of how MSE support policies are actually performing, especially what has been the impact of improved financing from the banking sector on MSE performance in terms of enterprise growth, value-added, investment and employment.

Second, the regulatory framework for MSEs is not well defined. Rules and regulations for MSE registration and eligibility for benefits including access to institutional finance assume that MSEs function in the formal sector whereas in reality all microenterprises and most small enterprises function in an informal environment. Consequently, most policies and regulations tend to bypass these enterprises.

Third, for the small enterprises, the licensing and access to finance requirements include having a tax ID, which militates against the incentive for enterprises to enter the formal sector. The issues concern information requirements, the transaction costs of compliance, and the fear of tax harassment.

Fourth, there is no central institutional support point for harnessing the MSEs. Several ministries, their related entities, and the Bangladesh Bank are involved in promoting MSEs. In practice, the Ministry of Industry and the Bangladesh Bank are most active. The main arm of the Ministry of Industry is the Small and Medium Enterprise Foundation (SMEF). The SMEF has a broad mandate but lacks the capacity to deliver on that. The Bangladesh Bank plays the lead role in providing institutional finance to small and medium enterprises. There is inadequate institutional coordination, which is one reason why a strategic vision and a road map are missing.

The most prominent intervention by the government has been on the financing side. By supporting the spread of the microfinance revolution through the PKSF and the Microfinance Regulatory Authority (MRA), the government has changed the landscape on the access to finance by microenterprises. Yet, this credit is very costly (23-24% interest rate) and there is unmet demand even at this high rate. The Bangladesh Bank though a major policy initiative adopted in 2011 sharply increased the supply of credit to small and medium enterprises from banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFI). The evidence shows that most of the benefits of institutional credit went to medium enterprises. Access of microenterprises is negligible and only 20% of the small enterprises are served.

The most prominent intervention by the government has been on the financing side. By supporting the spread of the microfinance revolution through the PKSF and the Microfinance Regulatory Authority (MRA), the government has changed the landscape on the access to finance by microenterprises. Yet, this credit is very costly (23-24% interest rate) and there is unmet demand even at this high rate.

Despite very attractive terms, most banks and NBFIs do not have an incentive to service the MSEs and as such have taken the easy way out to channel credit to medium enterprises as a means to comply with the Bangladesh Bank requirement. The disincentive has to do with several factors. A number of structural constraints in relation to MSEs limit their ability to benefit from institutional finance: perceived high credit risk, absence of property-based collateral, inadequate data and knowledge to prepare bankable projects, and lack of credit information. Several constraints also work from the financial institution side: weak understanding of MSE business, inadequate staffing, inadequate field presence, inappropriate business model, and lack of strategic thinking and vision.

A particularly problematic issue is the virtual absence of institutional supply of startup capital for MSEs, both debt and equity. Much of this has to do with the inefficiencies of the credit infrastructure reflected by the weakness of the credit information system, absence of securitized transactions, lack of the credit guarantee schemes, the high-cost nature of enforcing contracts and resolving insolvencies, and the absence of institutional support for the growth of startup enterprises.

A particularly problematic issue is the virtual absence of institutional supply of startup capital for MSEs, both debt and equity. Much of this has to do with the inefficiencies of the credit infrastructure reflected by the weakness of the credit information system, absence of securitized transactions, lack of the credit guarantee schemes, the high-cost nature of enforcing contracts and resolving insolvencies, and the absence of institutional support for the growth of startup enterprises.

Based on the above diagnostic of the financing challenges faced by MSEs and drawing on the lessons of good practice international experience, several policy options emerge. These can be broadly grouped under the following heads: (1) improving the enabling environment for the MSE sector through regulatory reforms; (2) strengthening the credit market infrastructure; (3) strengthening the institutional arrangements for MSE; and (4) promoting innovative financial solutions for MSEs.

Improving the Enabling Environment for MSEs through Regulatory Reforms

Refocusing attention to serve the business needs of micro and small enterprises

The inclusion of medium- sized firms in the definition of enterprises for policy support tends to divert the government’s policy interventions away from micro and small enterprises towards medium-sized enterprises. Except for a few low-end medium enterprises, most of the firms in this group face a business environment similar to large enterprises. The evidence from BB data on the outstanding portfolio of credit to small and medium enterprises suggest that the medium enterprises mostly benefited from these loans. These enterprises have good access to institutional credit and do not likely face a generic credit constraint. By clubbing together these enterprises with micro and small enterprises, the effectiveness of the BB credit initiative has been reduced as evidenced by the fact that banks have chosen to disproportionately serve this group. Similarly, firm registration and licensing requirements and support services tend to be guided by medium enterprise environment rather than by the needs of the micro and small enterprises.

One option will be to redefine the policy focus to exclude medium firms and rename it to micro and small enterprises (MSE) support facility. To ensure that firms in the low-end of the medium cluster do not fall out of the service radar because they are closer to the small enterprises rather than the medium enterprises, the definition of small could be revisited as was done in the past to have a somewhat larger coverage. The main point is that regulatory and support policies must be tailored to meet the needs of the small business and close all loopholes that allow larger enterprises that do not face similar constraints as the micro and small enterprises to hijack the gains from these policies, as seems to have been the case with BB’s financing policy for small and medium enterprises.

Adapting regulations to serve informal MSEs

The MSEs are characterized by a dominance of informal firms that are not registered with the government, do not have official business licenses, do not have a tax identification number (TIN) or a value-added tax (VAT) registration and do not pay taxes. As a result, they cannot benefit from policy initiatives intended for MSEs. This is a serious policy challenge with substantial political economy implications and must be handled with care. Most informal firms do not have any incentive to register irrespective of possible benefits including access to institutional credit due to the fear of being roped into the tax net and facing harassment and /or high transaction cost.

The underlying policy challenge emerges from the following dilemma. The MSEs should expand to create new employment and grow the economy. At the same time, the tax net must be widened to raise public resources for development. In principle the two objectives should be a part of the virtuous policy cycle. In practice, though they are in conflict. Bangladesh experienced this conflict in the case of the extension of the VAT to the informal retail sector. Owing to the political sensitivity of agitating the informal retail sector, the government decided to postpone the implementation of the VAT law. Learning from this political economy experience, a pragmatic option may be necessary to adapt the regulations regarding the support services for MSEs including access to finance in a way that reconciles the MSE expansion objective with tax regulations. An expert team of the National Board of Revenue (NBR), the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and the BB could be formed to look specifically how best to reconcile the two objectives. The government could also learn from the experience of other countries regarding how this policy dilemma could be best addressed.

Simplifying business procedures for MSEs

Similar to any business, the case for deregulating and simplifying the business licenses and clearance processes for MSEs is very strong. The main objective should be to encourage MSEs to become a part of the formal business environment and voluntarily comply with the regulatory requirements. The SMEF should also review the clearance procedures for manufacturing based MSEs. The application of the full range of regulations for medium and large manufacturing enterprises to micro and small enterprises would be an overkill. The objectives /of the simplification process should be to sharply reduce the transaction costs for MSEs with the removal of duplicate clearances, institution of low-cost and simplified online applications and award of clearances, and flexible labor laws.

Strengthening the Credit Market Infrastructure

The strengthening of the credit market infrastructure is a high priority reform to benefit the economy. The efficiency of credit market needs to improve sharply to enable better lending decisions and to reduce the incidence of non-performing loans. A stronger credit market infrastructure will be especially beneficial to MSEs owing to the information asymmetry they face in the financial market.

Improving the efficiency of credit market information

Bangladesh has limited experience with a credit information system (CIS) based on the BB-supported Credit Information Bureau (CIB). The reach of the CIB is limited and not helpful for MSE transactions. The main policy objectives for strengthening the credit reporting systems should be to have a robust and competitive credit markets through a credit-reporting system that is safe and efficient, and fully supportive of data that is relevant, accurate, and timely, and considers consumer rights. The governance arrangements of credit reporting service providers and data providers should ensure accountability, transparency and effectiveness in managing the risks associated with the business and fair access to the information by users. There should be an overall legal and regulatory framework for credit reporting, which should be clear, predictable, non-discriminatory, proportionate and supportive of data subject and consumer rights. The legal and regulatory framework should include effective judicial or extrajudicial dispute resolution mechanisms. While allowing credible privately managed credit reporting system, it is necessary to ensure effective regulation and oversight by BB or other relevant authorities. BB and other relevant authorities should have the powers and resources to carry out effectively their responsibilities in regulating and overseeing credit reporting systems. In strengthening the current CIS, Bangladesh can look at the structures of private credit information agencies in India, Philippines, or any other relevant country that has instituted a good credit information agency.

Enact law to set up Secured Transaction Register

Secured transactions play an enormously important role in a well-functioning market economy. Laws governing secured credit mitigate lenders’ risks of default and thereby increase the flow of capital and facilitate low-cost financing. Immovable property based collateral requirements in Bangladesh not only constrains the access of MSEs to formal credit, they also prevent the establishment of a secured transactions registry. Bangladesh faces a severe challenge in establishing land property rights, particularly in the lengthy and sometimes non-transparent process linked to establishing land title. This often limits the banks’ ability to fully enforce property rights received through collaterals. Therefore, in order to establish a well-functioning Secured Transactions Register the legal framework for secured lending should address the fundamental features and elements for the creation, recognition, and enforcement of security rights in all types of assets—movable and immovable, tangible and intangible— including inventories, receivables, proceeds, and future property, on a global basis, including both possessory and non-possessory rights.

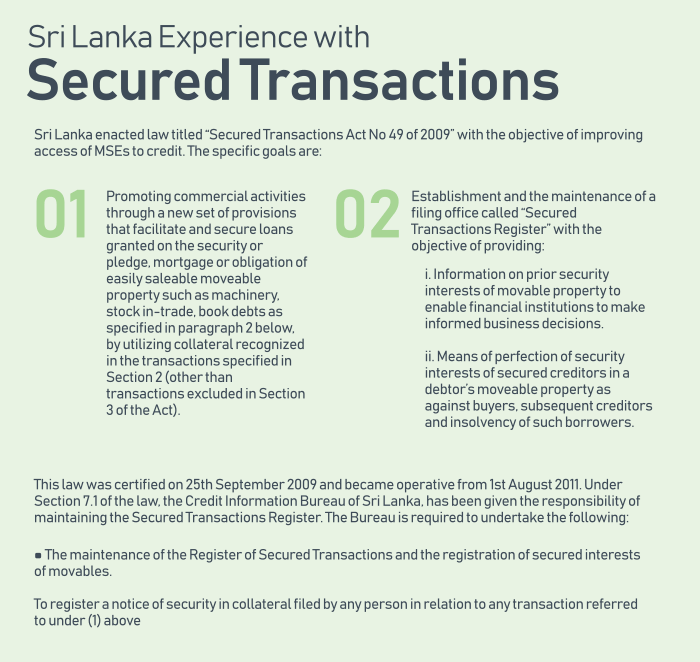

Bangladesh does not have any secured transaction register; efforts were made through different development partners (e.g. USAID and ADB) in having a law to facilitate forming of a Registry. Bangladesh could learn from other similar countries and use it to frame its own law and set up Registry. It can also learn from the experience of Sri Lanka (Box 1).

Strengthening the Institutional Arrangements for MSEs

Actions are needed on several fronts.

Establish a central coordinating agency to promote MSEs

The absence of a central support agency for MSEs suggests the need to consider ways to improve the institutional support system for MSEs. Presently, the two primary agencies for MSEs are the SMEF under the Ministry of Industries and the Small and Medium Enterprise Finance Department under the BB. Ideally, it would be best to have one stop shop arrangement like the Small Business Administration (SBA) in the USA to promote MSEs. In the USA, the SBA coordinates finance, regulations and technical assistance all under one window. Given that there are two institutions already in place in Bangladesh and to avoid the dislocation effects of rebuilding under one window, a second best and pragmatic option would be to assign the regulation, research and monitoring and evaluation functions to the SMEF and keep all financing issues under the Small and Medium Enterprise Department of the BB. As suggested earlier the BB financing window should be renamed Micro and Small Enterprise Financing Department by excluding medium enterprises and refocusing the entire facility to micro and small enterprises. The working of these two institutions should be jointly coordinated by the Ministry of Industry and the BB. The specific arrangements of this coordination mechanism could be worked out by the government. Other relevant ministries, like Finance and Commerce, should be represented as members in this coordinating committee.

Develop capacities of the banks and NBFIs to better service the financing needs of MSEs

Drawing on the successful experiences of the Brac Bank, the Prime Bank and IDLC, the Bangladesh Bank (BB) should ask each bank and NBFI for business plan about how they will move forward their MSE portfolio. The strategic business plan should include human resource plan, the MSE outreach plan, and the business model. BB should institute incentive measures for genuine structural/organizational changes to move forward the extended small enterprise agenda.

Establish small claims court

Bangladesh needs to review its Small Causes Courts Act 1887 and amend it to bring it in line with the Small Claims Courts in other countries (e.g., USA, UK, Australia, Singapore, and Kenya) for adjudicating small claim disputes between banks/NBFIs and micro and small enterprises. The jurisdiction of small-claims courts typically encompasses private disputes that involve small amounts of money. A small-claims court generally has a maximum monetary limit to the amount of judgments it can award, often in the thousands of dollars/pounds in those countries. Bangladesh could set an appropriate Taka limit for such cases.

Promoting Innovative Financing Solutions for MSEs

The availability of startup financing is a serious challenge for MSEs. The BB effort to strengthen the capacities of the banks and NBFIs to lend to MSEs will help but will not be enough. The active promotion of innovative financing options will be crucial.

Strengthen startup capital financing through the BB refinancing schemes

An important start-up instrument that has good prospects for growth in Bangladesh is start-up debt-financing from NBFI in the spirit of the US Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) model. There is already some good experience on this in Bangladesh pioneered by the Industrial Development Leasing Company (IDLC), the largest NBFI. The IDLC uses refinancing money from BB to finance start-ups and growth of micro and small enterprises at low interest rates. These features include: loan limit of up to 25 lacs; loan tenure of up to 5 years; grace period of 3 to 6 months; and repayment method could be equal monthly installment or structured payment. The IDLC approach can be mainstreamed by BB by establishing a similar window as the SBIC where the BB could pool together all donor funding along with some funding from the government to be used exclusively for financing NBFIs who are willing to provide start-up financing to micro and small enterprises. This can be a huge step forward in supporting the growth of MSEs even without any fundamental change in the credit market structure. So, this initiative can run alongside with reforms to improve the structure of the credit market.

Mainstream Credit Guarantee Scheme (CGS)

Bangladesh should institutionalize the CGS to improve access to finance. Bangladesh could use the World Bank suggested principles for CGS and learn from the models of India, Thailand and its own experiences with past efforts with CGS. There needs to be an effective institutional structure for a more broad-based Guarantee Scheme. There must be learning from previous failed government sponsored scheme involving the public-sector banks and there should be market tests for it. The choice of vehicle is a very important issue in this regard. Given governance concerns and the moral hazard problem, the best option would be to have a professional company funded by the government and participating banks/ NBFIs to run the guarantee scheme on a self-financing basis with full transparency of operations and full disclosure. The guarantee should be a partial risk guarantee with higher coverage for lower amounts and the risk premium should be adequate to ensure self-financing.

Promote digital financial services

BB needs to review its strategy and policy relating to digitization of financial services (DFS) and making the eco-system supportive for the growth of FinTech. A very important offshoot of a functioning DFS is e-commerce. This has potential to make the MSE sector grow and be a conduit for creating quality jobs. There already are many such companies in business – e.g. Daraz.com, Food panda, Bikroy.com, Chal Dal.com, Uber etc. to name a few. They are using the mobile and internet technology, which provides them the platform. These are startup firms that need to be nurtured to grow through adequate policy, regulatory and infrastructure support. At the same time, adequate safeguards should be in place to protect clients from fraudulent practices.

A critical supportive element will be to enable access to finance through FinTech and having in place an effective payment system. BB has been bringing in regulatory changes and has issued directives to the banks for starting e-Commerce activities. BB has permitted fund transfers up to BDT 5,00,000 from one clients account to another client’s account within the same bank using internet/online facilities subject to the fact that it will fully comply with prevailing Money Laundering Prevention legislations and related circulars. This area must be revisited as necessary to support the growth of e-commerce, DFS and FinTech. Different countries, including India and Pakistan, have already initiated changes to promote FinTechs. The focus should be to develop the right eco-system for FinTech evolution to be in place by changing any laws and regulations that impede a competitive DFS with opportunity for cashless transactions for e-commerce.

Promote FinTech options

On the FinTech side, the commonly cited challenges include an unfavorable attitude of incumbents for partnerships, a challenging regulatory environment, difficulty in modifying consumer behavior and lack of early-stage funding. The BB could issue necessary Circulars for FinTechs working with banks and those working independently to mitigate the challenges. BB should consider forming a dedicated FinTech Support Department that should collaborate with the National ID issuing authority, the Security Exchange Commission and BTRC to educate, observe and guide FinTechs, create FinTech regulations and participate in developing a regulatory framework.

Crowd funding, Angel funding and venture capital for MSEs

Bangladesh is still not well-placed to benefit from several other startup financing options like Crowd funding, Angel funding and more broadly Venture Capital. There have been limited efforts by private entrepreneurs to launch venture capital. A major problem is the weak financial infrastructure, especially the difficulties of enforcing contracts. Another problem is the mind set of small entrepreneurs who may not want to allow other people’s equity to enter into their business through venture capital for the fear of losing control. Learning from the US experience, the expansion of SIBC-type financing in Bangladesh will lay the foundations for the growth of venture capital for MSE start-up financing.