Shared Global Prosperity Calls for Revamping Governance of International Trade

By

A. The backdrop

Emerging out of the 1930s Great Depression and the Second World War, global economic prosperity was driven by a rapidly expanding regime of trade openness. That regime was launched following the Bretton Woods Summit in 1945 of leading global economies. In essence, what was launched was a cooperative scheme of geopolitics and geoeconomics, with endorsement of the leading powers that be. That Summit saw the making of several international institutions that last to this day. The World Bank was entrusted with financing postwar reconstruction and economic development, the international trading system was to conform to a rules-based order, initially through the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and its successor, the World Trade Organisation. The International Monetary Fund was charged with ensuring global financial stability, and organisations such as the United Nations offered frameworks for addressing geopolitical tensions.

The largely cooperative spirit of leading economic powers was able to maintain peace for several decades, a scenario that created the grounds for global economic prosperity. That cooperative spirit led to the evolution of intensifying cross-border integration of production, consumption and international trade in goods and services. The presumptive trend of international cooperation for globally distributed progress was what produced the inexorable forces of globalisation to a degree unimaginable in the 18th and 19th centuries.

But, even before the outbreak of the Russo-Ukraine war, deep fissures had appeared in this mosaic of international cooperation in the spheres of economics and geopolitics. Serious cracks appeared in the mirror of globalisation giving rise to bipolarity and multipolarity with the consequential outcome of multiple regional or ideological blocs that seemed to promote their own ideas of global security and prosperity. Cross-border integrated supply chains that evolved in an atmosphere of hyper-globalisation during the first decade of the 21st century were soon weaponised to become the economic instruments of de-globalisation. A recent IMF study found that global value chains (GVCs) accounted for 73% of total growth in global trade between 1993 and 2013. Since trade growth accounted for 70%of global GDP growth, GVCs were a critical driver of such growth.

The supply chain – the integration of fragmented components of production, assembly and distribution – has become the platform of the modern global economy. Designed interruption of supply chains has now become a new source of instability in an interdependent, globalised world economy. Indeed, the networks of globalisation, once a powerful force of economic, financial, and political integration, are now at risk of becoming new sources of fragmentation and divisiveness.

Global economic prosperity was cooperatively generated through the rules-based trade within a framework of international trade governance that was designed in the postwar years. Evolution of the structure and form of international trade over the past 75 years coupled with the latest fissures in the geopolitical landscape has made it imperative to revisit the format of international trade governance that appears to be out of synch with 21st century global flows of goods, services, capital, and digital information. A delicate but effective balance would have to be forged between democratic decision making in international forums and ensuring sovereign status of national policies. That is the challenge before the international community entrusted with guiding the international economy towards global financial and macroeconomic stability for future prosperity.

B. Trade openness and globalisation gains for 70 years

The missteps and perverse beggar-thy-neighbor policies during the Great Depression imparted critical lessons to the leading economic powers emerging from WWII. Leading economists of the time (e.g. John Maynard Keynes) along with global leaders were convinced that promoting trade openness was the way out of the Great Depression as well as the pathway to future prosperity. They were also cognizant of the need for workable institutions guiding the global governance of a rules-based trade order.

In this brief paper the focus is on the global governance of international trade relations as can be found in the operation of the apex multilateral trade institution – the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO – and its predecessor, GATT – emerged from the ashes of the Great Depression of the 1930s where, in the absence of any rules-based global trade institution, nation after nation resorted to beggar-thy-neighbor tariffs leading to the collapse of global trade and consequent deepening of the depression. It was global chaos unfolding in a world still steeped in poverty and rising from the devastation of a global war. Such a catastrophe had to be prevented for the future. So world leaders and leading economists of the world got together in 1945 at Bretton Woods and launched several multilateral institutions, one of which, i.e. General Agreement for Tariffs and Trade (GATT), was missioned to reduce tariffs and facilitate world trade. It is a matter of record that GATT and its successor, WTO, have been instrumental in reducing trade barriers around the globe, boosting trade growth for nearly 70 years, thereby fostering economic growth and lifting billions out of poverty.

The WTO has greatly extended its reach into non-traditional areas of trade policy. This has taken place against the reality that the WTO is only part of a more global structure of international agreements with overlapping objectives and commitments, many of which now find their place on centre-stage at the WTO. These commitments serve to shape domestic policy choices and constitute a principal feature of global governance. The WTO has a principal role to play in determining the borderline between domestic policy choices and international commitments. While the extended reach of the WTO is lauded by some as one of the greatest achievements in international cooperation, others see it as anathema, and an encroachment on national sovereignty.

Let us acknowledge that the WTO is not a perfect multilateral institution but if one reviews the progress in fulfilling its principal objectives there is much to cheer for. Though imperfect, a rules-based international trading system has evolved over the past 70 years after the second World War. It was the multilateral trading system that brought order to a chaotic world. World average tariffs are now down to a mere 6% and non-tariff barriers are down significantly (though not completely) such that world trade grew faster than income growth for almost 60 of the past 70 years, implying that trade was a driver of global income growth and thereby poverty reduction as well. Finally, WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism (DSM), with an appellate court, has been the most sought after international court and recognised as the jewel in its crown.

Sadly, over the past decade, multilateralism per se and trade multilateralism in particular has been under serious threat. The problem of course lies in its current system of governance. A prime example of this can be seen in the current state of the DSM. It has an appeals “court” that is the final arbiter on trade disputes and which has become dysfunctional because 2 of its 3 judges retired in December 2020 and the USA will not let them be replaced. And the court needs 3 judges to function. Though more than 100 members called for appointment of judges, the US alone said no. It’s the only country that has objected at any stage during this stand-off. And that effectively rendered the appellate court inoperative.

Lately, more insidious pursuit of a pattern of deglobalisation appears to be taking hold even among those states that were the postwar champions of free trade. Whereas the world is experiencing an inflationary spiral there are geopolitical moves to herald a new world that could be split into competing rather than collaborating trading blocs. This is evident from the idea of “friend-shoring” which is basically a strategy to steer trade to friendly nations (under some form of regional or global alliance) while hobbling trade with others. According to most trade economists these are protectionist moves in another name that would become the classic recipe for not just freezing global trade but also global economic growth in the future.

C. Post-war geopolitical order challenged

However, there is also the need for a close examination of the evolution of postwar governance institutions that emerged from the ashes of WWII. Global peace that followed the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Second World War presented an opportunity for the longest period of postwar reconstruction and prosperity. A liberal political order emerged out of the democratic process in the victorious power – the United States of America. Being the largest and most powerful economy emerging out of WWII, the dominance of USA in the global scene was all but guaranteed. Its allies, the liberal Western economies, joined forces to create governance institutions that reflected that liberal geopolitical order – built on foundations of political democracies, capitalist free market economies, and open trade. However, the Great Depression had produced a New Deal Keynesian economic order that encompassed government intervention in markets to combat deficiencies in demand and help stimulate growth and employment. That system underwent some change during the 1980s, under the presidency of US President Ronald Reagan.

US President Reagan added another dose of free market laissez faire economics (sans government intervention) that gave a new label – neoliberalism – to the prevailing dictum of geopolitics that was essentially based on western methods and conceptions of human society. In this order, private firms and the private sector were considered the key drivers of economies, not just in the USA but across the world. Private firms and companies gained an upper hand in mobilising resources and finding the most cost-efficient destination for investment. That provided the stimulus to evolution of cross-border production integration and GVCs in a new world of ‘hyper-globalisation’ during the 1990s and early 21st century. Private firms and multinationals (MNCs) in Europe, North America and East Asia began to feel a sense of ‘global citizenship’ that gave them the confidence to invest and operate any segment of production and distribution in locations far and wide. Cross-border GVCs generated tremendous efficiency dividends that reduced input costs and output prices in the global marketplace buttressed with corporate profits whose sources were hard to decipher except in the parent company, most of which were located in Europe and North America, but slowly and surely, were gaining ground in the East Asian markets.

But globalisation was primarily about cross-border integration in movement of goods, people, data, capital and financial flows, knowledge and information, technology, and research. Above all, the driving force behind globalisation was the augmentation of trade which, however, does produce winners and losers. Trade economists around the world, with few exceptions, feel strongly about the gains from open trade and investment to boost global prosperity. In theory, the case for winners to compensate losers is watertight, but in practice that is difficult to achieve, neither globally nor nationally. When winners and losers can be national entities or groups within particular economies, the compensatory principle becomes rather complex if not practically infeasible in application. That ruffles a lot of feathers in the political sphere giving rise to loud protestations against trade openness and globalisation as witnessed in the last decade when voter polarisation and shifting political power could be perceived as the consequences of the spread of globalisation. In consequence, the retreat of the forces of globalisation could be seen as good politics even in leading western economies wedded to the neoliberal order.

Global analysts doing in-depth research on the eventual costs and consequences of the new trend towards protectionism have described such schemes as ‘re-shoring’, ‘friend-shoring’, or‘strategic globalisation’. Some have even gone to the point of calling this trend as “shooting oneself in the foot” because of the signal abandonment of efficiency dividends for the world population arising out of open trade and globalisation. In particular, they point to the ‘China factor’ in ensuring low product prices and sustained low inflation for almost three decades during which China was accepted in the world community as a critical participant in producing global growth, low inflation, as well as poverty reduction. With tectonic shifts appearing in the geopolitical order following the outbreak of the Russo-Ukraine war, that perception of a perpetual trend in the growth and inflation trajectory is facing ‘unpredictability’ to say the least.

D. China’s role in global growth since the 1980s

Critiques of globalisation need to be looking in the rearview mirror to get a good sense of the process of evolution of this driving force of economic progress in the 21st century. The one socialist political leader, not wedded to western capitalism, who recognised the potentials of international trade as the immutable driving force of rapid economic progress was Chinese Premier, Deng Xiaoping. With China’s 1.3 billion population, most of whom were mired in poverty at the end of the Cultural Revolution, how could he ignore the galloping industrialisation and growth scenarios occurring in his neighbourhood – export-led prosperity of the Asian Tiger economies of SouthKorea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, subsequently labelled as the East Asia Miracle by the World Bank.

China under Deng was in a hurry to grow out of poverty. Deng changed the course of Chinese economic history with effect from 1978, thereby also changing the path of global growth by launching a system of global economic interdependence as a strategy for global prosperity. Deng opened China, a socialist inward-looking economy, to the world for trade and investment. Mutually reinforcing trade-investment-growth was the consequence – a win-win for China as well as the global economy. That arrangement lasted without much interruption for nearly three decades. However, what began as a trading relationship justified by Ricardian comparative advantage eventually transitioned into a complex multi-country assembly and production platforms with integrated supply chains or GVCs. GVCs have effectively transformed China from the factory of the world to the assembly line of the world in about three or four decades. Can this trend be reversed without heavy cost to the world citizens or global economy?

Of particular geopolitical and geoeconomic implications was the rapid rise in US-China trade and investment relations. When Deng first visited USA in 1979, US-China trade was only USD4 billion, miniscule in comparison to the USD 662 billion amount in 2018. More notable is the trade deficit of USD419 billion with China which accounted for 32% of US total trade deficit in 2018. China is still the third largest destination for US exports (9%) after Canada and Mexico, but the top sourcing country for imports (USD450 billion at 15%). Chinese imports from US which amounted to only 2% of US exports in 2000 grew at an annual average of 12% since then reaching 9% of total exports by 2021.

US needs China to buttress consumer purchasing power and business profits, while also relying on China for export demand. US lacks the domestic saving it needs to fund its budget deficit, fixed investment, and, ultimately, economic growth. China is essentially lending its surplus saving to a saving-short US, which is broadly reflected through its trade and current account deficits.

How should this economic relationship be defined? Interdependence or economic codependency? Over the years the Chinese economy has become tightly woven into the fabric of an increasingly globalised world—a strong manifestation of codependency of China’s broader relationship with the rest of the world.

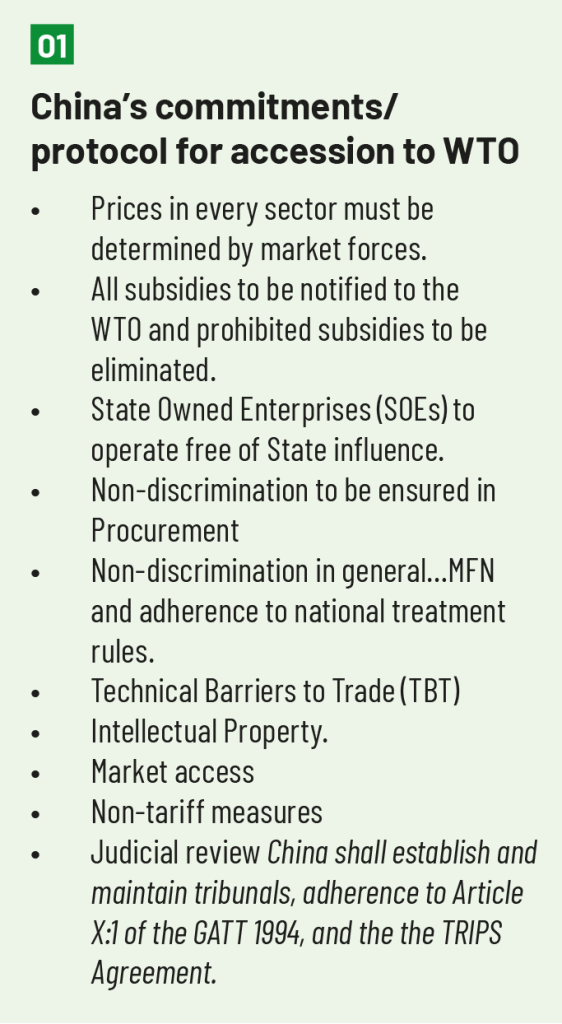

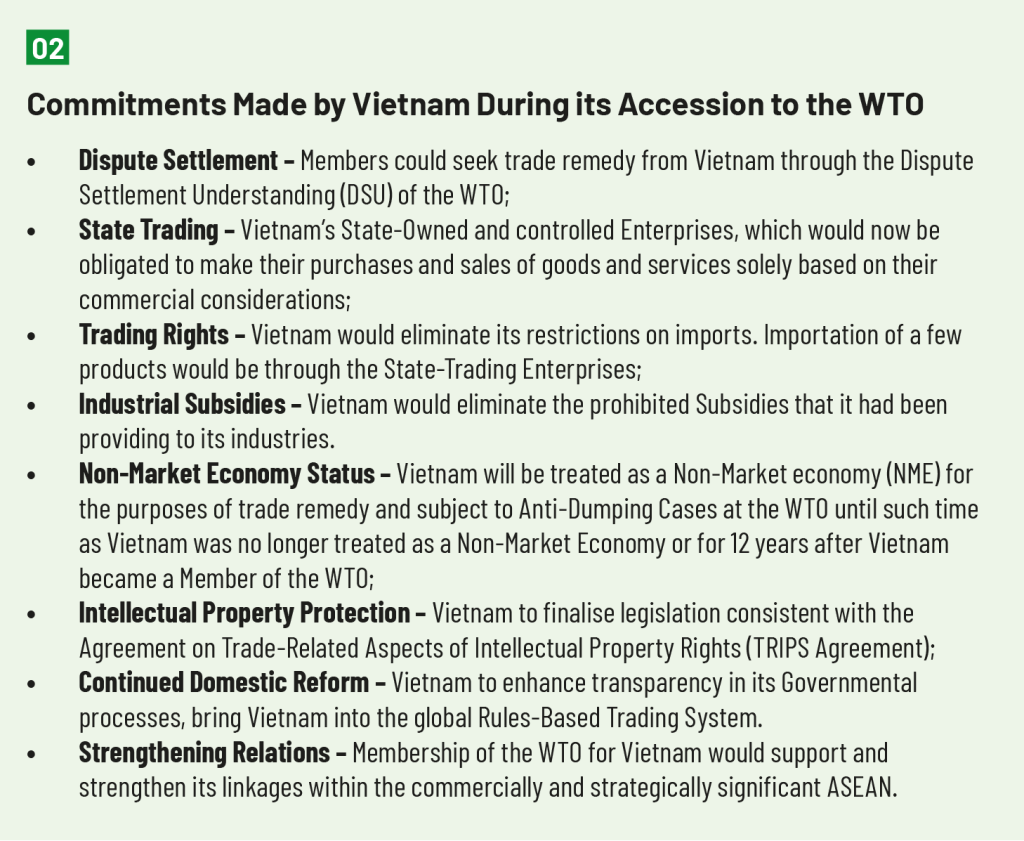

The codependency and economic interlinkages between China and the rest of the world was established through its accession to the WTO in 2001. Soon, another communist/socialist economy, Vietnam, joined the WTO club in 2007. These two communist countries found the benefits emerging from global rules-based trade too good to pass. So, they started negotiating for entry to the WTO that lasted 10-15 years for each of them. Given that they had economic systems at variance with the free market capitalist economic regimes, the two countries had to submit to stringent conditions for membership (protocols and commitments, see Boxes 1&2).

Prior to the accession of these two communist economies, the trading world was also splintered into the communist and non-communist groups of countries (Cold War grouping) where the communist bloc essentially managed inward looking closed economies that lacked significant trading relationships with the western world, particularly the OECD member countries. The fact that the two communist economies eventually gained accession to the WTO is a testimony to the cooperative spirit embedded in global governance of international trade. The overarching objective of maximising and sharing the gains of global trade that encompassed such a large economy as China eventually won the day. Entry of China, and then Vietnam, was considered to be mutually beneficial to these economies as well as the wider world community of 180 developed and developing economies that now make up the WTO.

Nevertheless, China’s accession documents reveal how unprecedented and complex the terms of accession were, with multiplicity of specific commitments, including many deviations permitted in order to facilitate accession (US Congress 2002,70). To open up to international trade and investment, China had to cut average tariffs and agree to bind them at a much lower level than what prevailed prior to accession. Additionally, China had to eliminate subsidies, quotas, licenses, and other nontariff barriers within a short period. It is only realistic to presume that gaps remain between China’s accession commitments and actual implementation. Once the spirit of cooperation (or rise in trust deficit) wanes these deviations could give rise to endless bickering that could stymy global trade.

While China had much to gain from the rules-based international trading system, it also had much to contribute to the world economy, with its large working population and competitive wages. Leveraging the global marketplace through international trade gave China over three decades of double-digit economic growth, something no economy in history was able to do. By 2015, China’s output was contributing to a third of global growth. As China suffered from lowering of its GDP growth figures, with its rebalancing strategies and the onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020, global growth also lost momentum from which it still has to pick up.

With an evolving global geopolitical landscape where China’s economy is being targeted as a source of the problem rather than the solution, can the world economy expect to continue on a path of low inflation and high growth that characterised economic progress over the 70 postwar years? That is a legitimate question that will need answers as global leaders meet in 2023 (G20 summit) to recast the geoeconomic map for coordinated policies that meet the goals of a contemporary world economy on a path of macroeconomic stability and sustainable growth.

E. Receding globalisation with decoupling trends

One cannot simply wish away the broad populist/nationalist backlash seen in advanced economies against globalisation, free trade, offshoring, labor migration, market-oriented policies, multilateral authorities, and even technological change. All of these forces have contributed to reduction in wages and employment for low-skill workers in labor-scarce and capital-rich advanced economies, while raising them in labor-abundant emerging economies. Consumers gained purchasing power in advanced economies from the reduction in prices of traded goods; but low and even some medium-skill workers lost income as they lost jobs or experienced lower wages.

Nevertheless, there is a strong realisation among international analysts that economic progress in the world, in particular, economic prosperity in the leading economies of the world – USA, China, EU – rests so much on the interlinkages and codependency built over the years between China and the rest. Then why let the trade war rage and leading economies start to abandon the hard-earned productivity and efficiency dividends of globalisation in a world challenged by repeated episodes of macroeconomic instability and the inexorable forces of climate change.

Perhaps the seeds of impending discord and conflict lay in the nature of the codependency itself. All the earlier enthusiasm to bring two communist economies – China and Vietnam – into the fold of market-oriented open capitalist economic systems is now proving in vain. The presumption that economic governance in these economies would eventually conform to the pure market mechanism and even lead to trends towards democratic political movements has not materialised. Perhaps this applies to China more than Vietnam as the latter has thus far been much more accommodating to the open trade system, capital flows and consumer demand. China’s commitments to embrace the neoliberal market economy and follow the norms of a competitive rules-based trading regime is being questioned on many grounds, some real and some perceived.

A sample of the related case for and against China’s economic governance as it relates to its posture in international trade is briefly presented here.

China became the 143rd member of the WTO on December 11, 2001. The key commitment that China made to gain accession was to embrace the WTO’s open, market-oriented approach and embed it in its trading system and institutions by swiftly removing trade barriers and open its markets to foreign companies and their exports. WTO members expected China to dismantle existing state-led, mercantilist policies and practices, and they expected China to continue on its path of economic reform and successfully complete a transformation to a market-oriented economy and trade regime. There were numerous other China-specific commitments like provisions to address issues related to injury that US or other WTO members’ industries and workers might experience on account of import surges or unfair trade practices, particularly during the transition period for China to move from a non-market to a market economy.

What is the record of China’s implementation of its commitments while joining the WTO? According to Pascal Lamy, the former Director general of WTO, it appears okay. If China did not comply, and it sometimes happened, it was taken to dispute settlement. China lost cases, and then abided.

One would have thought China was reneging on its commitments made at the time of its accession to WTO. But it is not like that. A closer review of the range of critique against China’s failure to fulfill its accession protocols leads one to the conclusion that the principal target of the critique lies with the Chinese brand of state capitalism and its role in the international trading system. Despite China’s decades-long reform process, the visible hand of the Chinese state remains strong. Though state ownership of industrial enterprises has declined in absolute terms the government has kept complete control over a small number of sectors that it regards as strategic. Chinese SOEs have grown in terms of asset value and revenues as well as presence on the international stage. Since SOEs as economic entities typically lack budget constraints (losses could then be equated with subsidies) their significant presence in international trade raise concerns about fair trade and competition.

Foreign business circles have consistently drawn attention to Chinese policy measures – subsidies, local content and technology transfer requirements, disregard for intellectual property rights and discrimination against foreign companies in favor of domestic actor that could violate WTO regulations. Then there are the WTO’s institutional limitations in regulating China’s industrial policy measures, especially the ineffectiveness of the WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. The narrow definition of what constitutes a subsidy with the focus on the financial contribution by ‘a government or public body’ allows SOEs to escape scrutiny.

As for the second critique, to consider China, now the second largest economy in the world and soon to become the largest in nominal GDP terms by 2030, as a developing economy raises issues of fair play in international competition. Even more intractable is the issue of China (or Vietnam) being a non-market economy, a departure from the kind of market economies expected to be members of WTO. With Chinese SOEs now playing significant role in export trade with access to government subsidies raises pertinent questions of fairness in international competition in the global marketplace. At bottom, these are agonising factors that are holding up US approval of appointment of judges to the appellate court.

Against these critiques, Maichael Lennard, a UN expert on interpretation of WTO laws, opines that the Accession Protocol for China contradicted the legal principle of in dubio mitius, that states are sovereign over their own territory, and was ‘inherently one sided in that it imposes special burdens on one side (China) as the ‘price of admission’ to the WTO’(Lennard, 2003, Interpreting China’s accession protocol: A case study in anti-dumping in China and the World Trading System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). The idea that if Chinese prices were lower than those of a comparable market competitor, such as Malaysia, this was deemed to be unfair competition and so subject to possible sanction, defies market logic. Lennard further noted that for fifteen years after accession, Chinese exporters of goods imported by a WTO member were required to show that ‘market economy conditions prevail in the industry producing the like product’ (Lennard, 2003). These were harsh conditions, to say the least.

China responded to recent critiques through a position paper, as follows: (a) economies differ from each other, so there is need to ‘respect members’ development models;’ (b) on the procedural issue of subsidy notifications, China was willing to conform and advised developed countries to lead by example with their notifications as well; (c) with regard to S&DT, this is an ‘entitlement’ that China ‘will never agree to be deprived of’. At the same time, China also indicated its willingness to ‘take up commitments commensurate with its level of development and economic capability’.

After 40 years of Cold War 1.0 during which global trade remained split into the socialist camp and the rest of the world, the governance of international trade under WTO launched a major experiment – incorporating two socialist economies into the fold of global trade early in the 21st century. Convinced that their entry into the world trading community would fuel high growth and poverty reduction the two socialist members – China and Vietnam — enthusiastically joined the WTO and were prepared to commit to stringent accession requirements. That arrangement paid off handsomely, to the new members as well as the world community. China got three decades of record double-digit growth to become the top exporter in the world while Vietnam has become an export powerhouse with export-GDP ratio reaching 100% in 2021. The two economies now account for 25% of world trade of about USD 25 trillion. The world economy saw rapid growth fueled by fast-paced trade growth and a long period of disinflation in product markets resulting from cheaper imports from China and East Asia.

That honeymoon period seems to be turning a corner with revisionist thinking about the benefits of such globalisation. Geopolitical cracks have appeared on US-China codependency built up over four decades. The trade war that was launched during the Trump administration continues without any sign of abating, hurting both sides. In fact, it has morphed into a tech war that threatens to be even more inhibiting to global progress in the future. Protectionism has raised its ugly head in the garb of “friend-shoring” and “re-shoring” even in those economies that were the champions of free trade.

Is globalisation dead or just in temporary retreat? Leading defenders of globalisation argue that it is too deeply entrenched in the world ecosystem to be abandoned anytime soon. But trends in US-China or China-West decoupling are noticeable and further compounded by the ripple effects of the Russo-Ukraine war. The costs in terms of inflationary impacts and loss of consumer purchasing power, even macroeconomic stability, will be high by any measure. The costs in terns of future global progress and sustainability are even more unpredictable.

With tectonic shifts in geopolitics in the aftermath of the Russo-Ukraine war, there is no doubt that globalisation will have to change but leading economic historians are of the opinion that globalisation has taken hold enough to belie any pessimistic predictions about its lasting power.

F. China factor goes global

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1990 marks the end of Cold War 1.0 thus launching a period of peace dividend that lasted some thirty years and created the forces of unbridled globalisation in which socialist and neoliberal market economies could prosper under one roof of rules-based trade. The rise of China and Vietnam as export powerhouses showed the world the latent potentials in socialist economic systems once they embraced doses of market economy. But it also sowed the seeds of competition that could morph into conflict as signaled by the US-China trade and tech war. A grim reminder of ancient history reveals the dark side of conflict between a rising power and an incumbent super power – which Henry Kissinger, architect of the Sino-US friendship breakthrough in the 1970s, reminded us as approaching the so-called Thucydides trap. The initial frictions of a trade war has morphed into a tech war that seems to be catapulting into a 21st century version of a cold war (Cold War 2.0) with perilous consequences of such a clash for humanity: economic inefficiencies, geopolitical tensions, and even growing risks of a broader world war. The China factor has global implications, now and in the future.

In the late 1970s and 1980s both USA and China needed each other. China sorely needed a way out of massive poverty of its vast population and savings-starved USA needed investible resources to fuel productivity and growth. US economy provided consumer demand to buttress Chines exports for three decades creating larger US trade deficits over time that was then financed by surplus Chinese savings. Chinese preference for dollar denominated assets, as they accumulated reserves from trade surpluses, produced the capital inflows to finance trade and current account deficits. It was a marriage of convenience – a codependency – that worked fine for a savings-short US economy. But such codependency also produces the sources of conflict that began to be seen in political movements like Make America Great Again (MAGA). While Chinese exports produced disinflation and higher purchasing power to US consumers, it came at the cost of closure of high cost industrial units across middle America wiping out industrial belts around the country. The China factor appeared to be a mixed blessing as China was then blamed for the rising trade deficits and this deindustrialisation trend.

Unfair trade, non-compliance with WTO commitments, dominance of SOEs in China’s export trade, state-directed targeted industrial development (China is hardly alone in the art and practice of industrial policy), were some of the arguments put forth in the USTR’s Section 301 filings with WTO. While some of these arguments may be plausible, the search for a balanced narrative is required to reach a workable understanding that could save the world from being hobbled by US-China trade discord. It is not clear to me that the Chinese economy, which sticks to being a socialist economy, only embraces the market economic system with Chinese characteristics. If converting the Chinese economy into a full-fledged capitalist economy was expected to be the ultimate goal of accepting China’s accession to WTO, by the neoliberal powers managing governance of international trade, then one has to come away with the feeling that, in the end, this would be an exercise in futility. Because this would constitute an encroachment in the sovereignty of a member country and its pursuit of a distinct development model, unlike any other.

In sum, the China factor is hobbling the WTO? One would have thought China was reneging on its commitments made at the time of its accession to WTO. But that is not it. There appears to be two fundamental bones of contention between the US and China in terms of rules and practices: (a) calling China a developing economy that entitles it to S&D treatment accorded to developing economies, and (b) China’s non-market economic practices (enormous role of SOEs that are heavily subsidized) that are shielded under existing rules and dispute settlement mechanism.

To consider China, now the second largest economy in the world and soon to become the largest in nominal GDP terms by 2030, as a developing economy raises issues of fair play in international competition. Even more intractable is the issue of China (or Vietnam) being a non-market economy, a departure from the kind of market economies expected to be members of WTO. With Chinese SOEs now playing significant role in export trade with access to government subsidies raises pertinent questions of fairness in international competition in the global marketplace. At bottom, these are agonizing factors that are holding up US approval of appointment of judges to the appellate court.

All of these are significant issues impinging on global governance of international trade and resolution require strong commitment to cooperative endeavours.

G. World needs a different brand of globalisation

After decades of globalisation, the judgment is clear. Within limits, globalization has been good economics but its impacts have not led to good geopolitical trends worldwide. But the answer to this trend does not lie in global economic fragmentation but in modernisation of global governance institutions in line with evolutionary trends of the 21st century. If global economic fragmentation becomes the dominant theme cooperation on issues and policies affecting global stability, crisis prevention and resolution may become more challenging. So it is in the interest of the world community to sustain the intrinsic benefits of globalisation by suitably adapting to a changing world economy and polity.

All indications are that the era of hyper-globalisation, which had its beginnings in the early 1990s, is over. That has important implications for the effectiveness of governance of international trade relations. But that doesn’t mean that we stop thinking about global trade in the backdrop of some form of global cross-border interlinkages of goods, services, capital, energy, data and information flows, which will perhaps constitute another variant of globalisation. After decades of heightened connectivity, economies cannot suddenly become islands. Technological advance will not permit that from happening. In which case global rules, global agreements, and global institutions will have to be newly crafted, or old rules revamped under changing or evolving patterns of international trade relations. That is, governance of international trade will continue to be the global public good in demand, such that a more effective and revamped WTO might become absolutely essential for a prosperous shared future of mankind.

A revamped WTO of the future must be able to address some of the fundamental critiques of past globalisation:

The new globalisation must be more inclusive ensuring a better distribution of the gains from trade. There cannot be huge divergence between winners and losers from globalisation. In the last, winners were the global top 1%, the middle class in newly emerging economies, and high-skilled workforce. The bottom, middle, and working classes in advanced countries were the losers. A mechanism must be in place for redistribution of gains from winners to losers, across countries and within countries.

A better balance between the prerogative of national sovereignty (in different economic systems) and the requirements of an open economy must be ensured to enable inclusive prosperity at home and peace and prosperity abroad (Dani Rodrik, 2016, The False Economic Promise of Global Governance, in Project Syndicate). Absence of this is what created conflict between the state interventionist policies of China Inc. and liberal principles enshrined in the world trading system. With different economic systems in play (socialist vs capitalist) at a world forum like WTO, countries would like to safeguard the integrity of their regulations under their own specific institutions presenting the ultimate challenge of cross-border coordination. The value of policy autonomy must be taken into account.

Some international analysts have blamed the Bretton Woods system for pursuing the global economy as the end that would bring employment, prosperity, and equity within the domestic economies. Which is why we find so much domestic divide and inequality arising out of international integration forces of globalisation.

If sanity prevails in geopolitics of the future, the so-called Thucydides Trap is not necessarily a fait accompli. Whereas US-China economic interdependence was built on the understanding of mutually beneficial codependency, a positive-sum approach to China’s economic and technological advance has the potential to yield higher productivity and the disinflationary trends that the world needs today. But then the US would have to first accept the idea of multipolarity in global leadership.

At the end of the day, it appears that the rise of China as a geopolitical rival of the US has pushed strategic competition above economic principles and market analytics. In recent times, the positive-sum logic of cooperative global governance espoused under the Bretton Woods era has taken the back seat to be replaced by the “zero-sum logic of national security and geopolitical competition” (Rodrik, 2016). Sadly, the forces of escalation have become self-reinforcing, and quite possibly self-defeating. The world community must come together and put a stop to this trend.

To conclude, while geopolitics will determine the success or failure of global governance institutions like the WTO, global leaders have the extra responsibility to rise above the immiserising tendencies to move towards a trading architecture that restricts rather than propels the flow of cross-border movement of goods, services, capital, energy, and information. Regardless of the degree of globalization that is congenial for the world, the global community, with diverse economic systems, has the unenviable responsibility of leaving a more dynamic trading architecture that fuels prosperity with inclusiveness and environmental sustainability for future generations. In particular, the new trade architecture must have mechanisms in place such that globalisation’s potential losers experience the gains from trade and join the ranks of winners.

It is important to recognise that by and large globalisation has been a boon to the world’s population as it helped improve living standards in many countries, with over a billion people lifted out of extreme poverty over recent decades. The legacy and benefits of globalisation are worth preserving.

Only the future can tell us if the global community is headed in the right direction this time as they did in the post-War period. But none can deny that international trade and economic interconnectedness and interdependence of economies is a reality of the past, the present, and much more so for the future, something that cannot be ignored. It is a global imperative that a suitable system of global governance of international trade evolves in the interest of promoting shared prosperity around the globe in the 21st century and beyond.