Measuring cost of violence against women

By

Introduction

Referring to a paper by Fearon and Hoeffler (2014), Lomborg and Williams in an op-ed in The Washington Post recently concluded that the ‘the cost of domestic violence is astonishing’. Fearon and Hoeffler (2014) found that the cost of domestic violence was 11.1% of world gross domestic product (GDP). Costs related to violence against women and girls (VAWG) and child abuse have also been high, respectively, at 5.3% and 4.3% of global GDP. These numbers seem plausible given the high incidence of VAWG referred to by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank.

VAWG is an epidemic affecting one in three women worldwide in their adult lifetime (WHO, 2013). Globally, women aged 15–44 are more at risk of rape and domestic violence than of cancer, motor accidents, war and malaria combined (World Bank, 1994). In addition to being a major violation of human rights and a significant public health issue, VAWG exerts a significant cost on the economy. In recognition of its impact on society, advanced economies have undertaken research to measure the economic cost of VAWG and thereby adopted strategies to tackle it. Following the first attempt to measure this economic cost, carried out in Australia in 1984, based on data from only 24 female victims, a growing number of studies have been conducted. Most of these studies are based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and have for the most part measured the direct economic costs (costs associated with services).

Our literature review identified the use of four types of methods to estimate the economic cost of VAW. Three of these—namely, the econometric method, the ‘willingness to pay’ method and Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYS)—require a large amount of data and parameters. These three methods have been used in OECD countries, where such information is more readily available. The fourth approach, known as ‘the accounting type method’, is much simpler to comprehend and implement. 1

Although prevalence of VAWG is high in developing nations, measuring its cost so as to be able to adopt strategies to tackle it has been hindered by the lack of availability of an appropriate toolkit. Against this backdrop, the Commonwealth Secretariat launched a project to develop an implementable toolkit to measure the economic cost of VAWG in developing nations or countries with weak statistics. This article presents the key features of the toolkit and the outcome of its application in a member country—Seychelles.

…the Commonwealth Secretariat launched a project to develop an implementable toolkit to measure the economic cost of VAWG in developing nations or countries with weak statistics. This article presents the key features of the toolkit and the outcome of its application in a member country—Seychelles.

A costing toolkit for developing countries

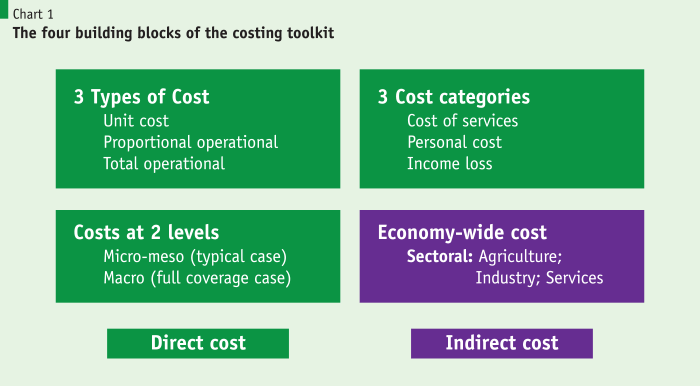

The costing toolkit consists of four building blocks. There are three building blocks for the direct cost component and one building block for the indirect cost component.

Considering the features of these four methods, and in particular the data need, the accounting type method has been deemed most appropriate for developing countries, as other methods require more information on data and parameters, as noted above.

The direct cost component has three blocks.

- Three types of cost approaches: The estimated costs are based on three types of approaches—(i) the unit cost approach; (ii) the proportional operating cost approach; and (iii) the total operational cost approach. The first estimates the cost of a certain service package provided to a survivor in a certain case (e.g. per day hospital cost or medical service package for grievous wound survivor). The second is based on identifying the share of survivors in the total number of service recipients (e.g. 30% of the total social services budget spent for survivors). The third is applicable to 24-hour 7-day services (such as a telephone hotline for survivors of violence).

- Three categories of costs: The estimates are produced for the following potential three categories of costs: (i) services provided in response to violence and assistance for survivors. These may be in health care, law enforcement and the justice system, penitentiary institutions for abusers, social and specialised services for women affected by violence, etc.; (ii) personal material losses and cash expenses of survivors owing to violence; and (iii) lost economic output owing to irreversible population losses such as premature death of women, temporary and permanent disability and reduced work productivity of survivors, leading to a loss in output or income.

- Costs estimated at two levels: An important observation is the high latency of offences against women and girls according to official statistics (for obvious reasons such fear of being stigmatised, of being blamed for provocative behaviour or of retaliation by the abuser). Thus, estimates based only on official statistics may significantly underestimate the economic cost of violence (since the official data misrepresent the real magnitude). Thus, a sensible approach may include costs estimated at two levels or using two scenarios. First is a cost estimation based on official or survey data (in other words based on micro- and meso-level data)—in other words an economic cost estimate based on a ‘typical’ scenario using the official police statistics on offences. Second is a ‘full coverage’ scenario based on a simulation model using the violence prevalence rates and features of survivors contained in population-based surveys. This may also be referred to as a macro-level cost estimate.

Indirect cost: We live in a highly interdependent economic system where the impact on a group of individuals (the directly affected group) transmits to other, indirectly affected, groups. The empirical economic literature has found that total indirect impacts are also substantial if not higher than the value of the direct impact. The direct cost component does not capture the indirect cost of VAW.

The concept of the direct and indirect impacts can be illustrated using the example of a pond into which a pebble has been thrown. Where the pebble hits the pond is the epicentre. The impact also creates impulses (or series of waves) around the epicentre. The extent of impulses varies with the severity of the impact at the epicentre. The epicentre may be considered the direct impact (or in this case the direct cost of VAW). The waves (or impulses) are the indirect impacts. The sum of all these waves constitutes the indirect impact (or in this case the indirect cost of VAW).

To assess the indirect cost of VAW, we use a simple economy-wide framework. Consider an economy with earnings and spending. We earn our income from various types of activities (i.e. agriculture, manufacturing, mining, construction and services, etc.) by investing our financial resources (or capital) or through participating in the labour market (i.e. in economic jargon, capital and labour are known as factors of production). The vast majority of what we earn is spent (or consumed) on various types of commodities and services. Spending or consumption generates demand for commodities and services, which stimulates supply of various activities where these are produced. Stimulated supply employs labour and capital and thus creates income for spending again—and the loop continues.

The estimated cost of VAW

The costing framework for VAWG was numerically specified to 2016 data and parameters.

Total estimated cost of VAW

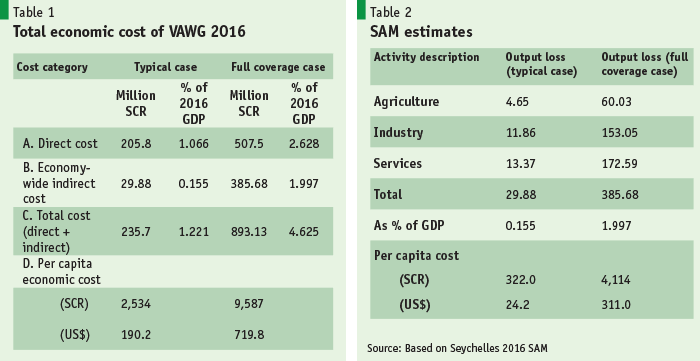

The estimated economic cost of VAWG in Seychelles is high. The estimated total cost in 2016 under the typical case is SCR 235.7 million. The estimated direct cost is SCR 205.8 million and the economy =0wide indirect cost is SCR 29.9 million. GDP in 2016 was SCR 19,014 million. Hence, the total cost under the typical case is 1.221% of 2016 GDP. The direct cost and indirect cost as a share of 2016 GDP is 1.066% and 0.155%, respectively.

The total cost under the full coverage case has been estimated as SCR 893.1 million. The estimated direct cost is SCR 507.5 million and the economy-wide indirect cost is SCR 385.7 million. In terms of GDP, the total cost is 4.625%; the direct cost is 2.628% and the economy-wide indirect cost is 1.997%.

Economy-wide indirect cost

The economy of Seychelles for 2016 is delineated by an economy-wide dataset known as the Social Accounting Matrix (SAM). The SAM consists of 16 activities, 2 factors of production and 4 institutions. The data SAM is converted into a SAM multiplier model by defining endogenous accounts (i.e. in this case 16 activities) and exogenous accounts (i.e. including private consumption demand vector). Thus, the SAM multiplier model is composed of 16 x 16 accounts.

To carry out the consumption reduction shock on the economy using the SAM multipliers model, the 2016 consumption values are adjusted downward for each of 16 activities. Following this approach, two consumption shocks were set up—one for a typical case (i.e. reduction of consumption or spending by SCR 15.8 million) and one for a full coverage case (i.e. reduction of consumption or spending by SCR 239.8 million). These shocks are then used with the multiplier model to simulate output loss under the typical case and full coverage case. The simulated results by three broad sectors are provided below.

Typical case

The simulated output loss under the typical case is SCR 29.8 million or 0.155% of 2016 GDP. The services sector is found to be the most affected among the three broad sector categories, with a bill of SCR 13.4 million. The output loss for industry is simulated at SCR 11.8 million, with other manufacturing and food processing bearing the major loss. Agriculture is least affected, with an output loss of SCR 4.7 million.

Full coverage case

The simulated output loss under the full coverage case is SCR 385.7 million or 1.997% of 2016 GDP. Again, the services sector is the most affected among the three broad sector categories, with a bill of SCR 172.6 million. Industry may experience an output loss of SCR 153.1 million. Agriculture is least affected, with an output loss of SCR 60 million.

Key findings

- The total economic cost of VAWG in Seychelles is almost 1 percentage point higher than the total education budget for 2016, which was SCR 663 million, or 3.5% of GDP. The implication is that, if VAWG were eliminated in Seychelles, the education budget could have been doubled, with far-reaching salutary effects on productivity, poverty and welfare.

- The economic cost of VAWG for every person in Seychelles is also high. The per capita economic cost of VAWG under a typical case is SCR 2,534, or $190. Per capita economic costs of VAWG under the full coverage case escalated to SCR 9,587, or $720.

- The private sector is not immune to the cost of VAW. The use of an economy-wide model reveals some interesting implications for the private sector. Almost all of these 16 activities or sectors are run by the private sector. Per year output loss to the private sector owing to VAWG is SCR 385.7 million, or almost 2% of GDP. This is a large figure for any private sector group. Given this high loss, elimination of VAWG in Seychelles should also be a priority for the private sector.

…1 percentage point higher than the total education budget for 2016, which was SCR 663 million, or 3.5% of GDP. The implication is that, if VAWG were eliminated in Seychelles, the education budget could have been doubled, with far-reaching salutary effects on productivity, poverty and welfare.

Interventions

The research concludes that the estimated economic cost of VAWG in Seychelles is high. This aspect, coupled with the high economic cost of VAW, requires immediate and effective actions by the national authority. Some of the recommended actions include:

Enabling policy

- Engaging policy-makers, officials and programme stakeholders to acknowledge VAWG as a priority development issue by preparing and implementing an adequately funded plan of actions;

- Implementing a multi-sectoral and inter-ministerial response to VAWG through establishing mechanisms focusing on coordination and accountability;

- Designing and implementing a comprehensive communication strategy involving communities, individual stakeholders including men and boys, government, non-governmental and civil society organisations and the private sector.

Strengthening capacity

- Strengthening capacity of the national statistics office and administrative agencies in data collection on VAWG for designing effective strategies and monitoring of progress;

- Designing a data collection protocol for front-line service providers (e.g. health care, police, judiciary, etc.) using computer enabling software for faster collection, processing and sharing;

- Buttressing the capacity of front-line service providers such as police, social services and health care for effective service delivery as well as to improve collection and maintenance of records in a suitable format and environment;

- Providing training and capacity-building for health service providers, police, judiciary, managers and policy-makers to equip them with the skills and knowledge necessary to address VAWG as part of a multi-sectoral rights-based response.

Scaling up the budget

- Operationalising dedicated shelters for VAWG survivors providing support such as medical care, accommodation, food, counselling and legal aid;

- Establishing and operationalising a dedicated hotline for VAWG;

- Scaling up investments in primary prevention and establishing a dedicated budget to address VAWG across ministries as well as providing sustainable funding to specialist women’s organisations.

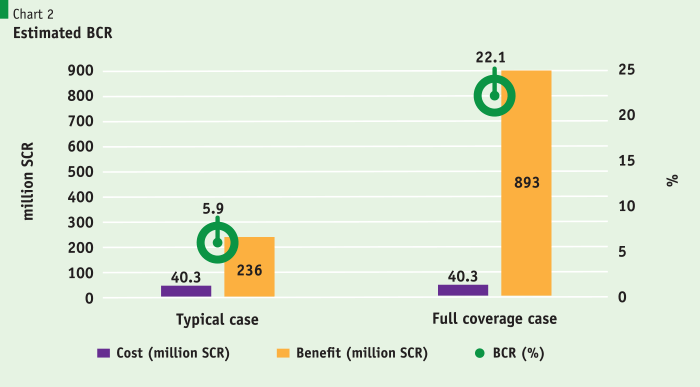

The estimated resource needs to carry out the above-mentioned interventions is estimated at SCR 40.3 million at 2016 prices. The benefit-cost ratio (BCR) contrasts the estimated present value of all benefits against the present value of all costs to assess the feasibility of a project from both a financial and an economic perspective. A project is feasible if the BCR is greater than one (1).

BCR = (Present value of benefits) / (Present value of costs); Project viable is BCR > 1

To estimate the BCR, along with intervention amounts (cost of interventions), benefit amounts are also needed. Reducing or eliminating the costs of VAWG are the expected benefits of the interventions outlined above. Since we consider two estimates—a typical case and full coverage—we also provide the expected benefits of these. Those under a typical case are SCR 236 million at 2016 prices. Under the full coverage case the benefits are SCR 893 million at 2016 prices. Thus, the estimated BCR for the typical case is 5.9 (=236/40.3). The estimated BCR for full coverage is higher, at 22.1 (=893/40.3).

The Seychelles costing toolkit is based on official data and covers several important services, such as health care, law enforcement, social services and specialised services.

Conclusion

The costing toolkit developed under the aegis of the Commonwealth Secretariat has been numerically specified with data from a member country—Seychelles. The Seychelles costing toolkit is based on official data and covers several important services, such as health care, law enforcement, social services and specialised services. It also includes out-of-pocket personal costs incurred by VAWG survivors and the cost of learning time loss at schools. Moreover, income loss because of absence from paid work and household activities is also estimated. The effort could not include important costs related to emotional intimate partner violence and work place violence, etc.

The major advantage of this toolkit is that it is developed in an MS Excel environment and thus can be transferred to government counterparts (as well to other stakeholders) with focused training. A modular approach was considered in developing it such that multiple developers can work simultaneously on different model components. The most important merit is that it is a live product—it allows updates, modifications and extensions to be carried out with ease.