WTO Agreement offers lifeline to Marine Fisheries Development in Bangladesh

By

Overfishing from marine is a crucial issue around the world. Due to overfishing, fish depletion drastically reduces stock size, which can ultimately reduce global fish production if higher reproduction rates are not in place. Thus, the contribution of this sector to global food and nutrition security may hamper enormously.

Overfishing occurs due to providing some harmful subsidies to lower the cost of fishing operations which encourage illegal, unreported, & unregulated (IUU) fishing and fishing in high seas (the open ocean, especially that not within any country’s jurisdiction).

Due to overfishing, fish depletion drastically reduces stock size, which can ultimately reduce global fish production if higher reproduction rates are not in place. Thus, the contribution of this sector to global food and nutrition security may hamper enormously.

Following several years of talks at different World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Conferences (MCs), the UN General Assembly (2015) provided an additional impetus for the elimination of harmful subsidies taking into account the importance of this sector to development priorities, poverty reduction, and food security concerns for developing and least-developed countries (LDCs). Despite intense negotiations, members were unable to reach an Agreement at the 11th WTO MC in 2017. Instead, ministers mandated prolonged discussions based on emerging consolidated texts and set a deadline for the talks to be completed by the next MC.

Finally, after huge textual proposals, in 2022 at the twelfth MC, for the first time, WTO reached a multilateral Agreement to provide sustainability by giving new rules and prohibitions on some harmful fisheries subsidies. But as a special and differential treatment (S&DT), the developing and least-developing countries will be exempted for two years. The key provisions of the Agreement are as follows:

First one is the prohibition on subsidy to a vessel or operator engaged in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing or fishing-related activities mentioned in Article 3. The second, mentioned in article 4, prohibits subsidies for fishing or fishing-related activities regarding overfished stocks and the third one mentioned in article 5, states that WTO members shall not grant or maintain any subsidy for fishing in the unregulated high seas.

Now, the question is how an LDC like Bangladesh will be benefited or be hampered by the given WTO fisheries subsidies Agreement.

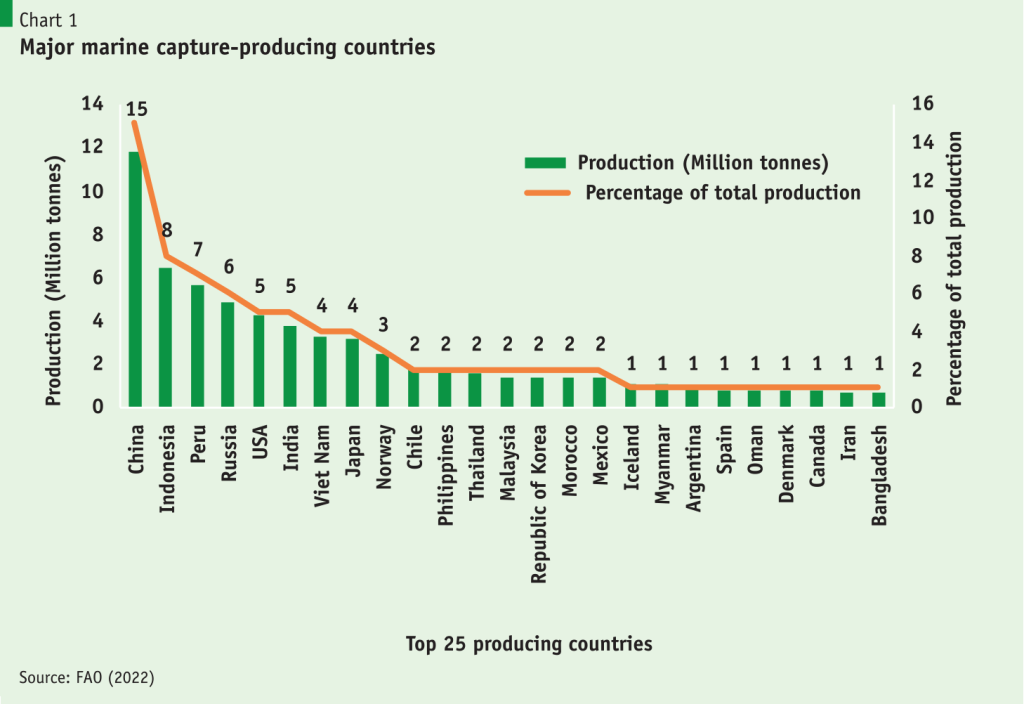

Before investigating we need a brief understanding of the fisheries sector in Bangladesh. Fisheries and aquaculture play a key role in the economy of Bangladesh directly and indirectly by reducing poverty and improving livelihoods and contributing to food security, employment, and economic empowerment. It contributes 3.57% to GDP, accounting for 26.50% of agricultural GDP, and 12% of national employment. According to the Department of Fisheries (DoF), the fisheries sector is divided into three sub-groups inland aquaculture, inland capture, and marine capture. Marine aquaculture is underdeveloped in Bangladesh. Marine capture currently contributes only 15% of the total fish production in Bangladesh and 1% of the total world marine production, which is far behind the other top-producing countries (Chart 1).

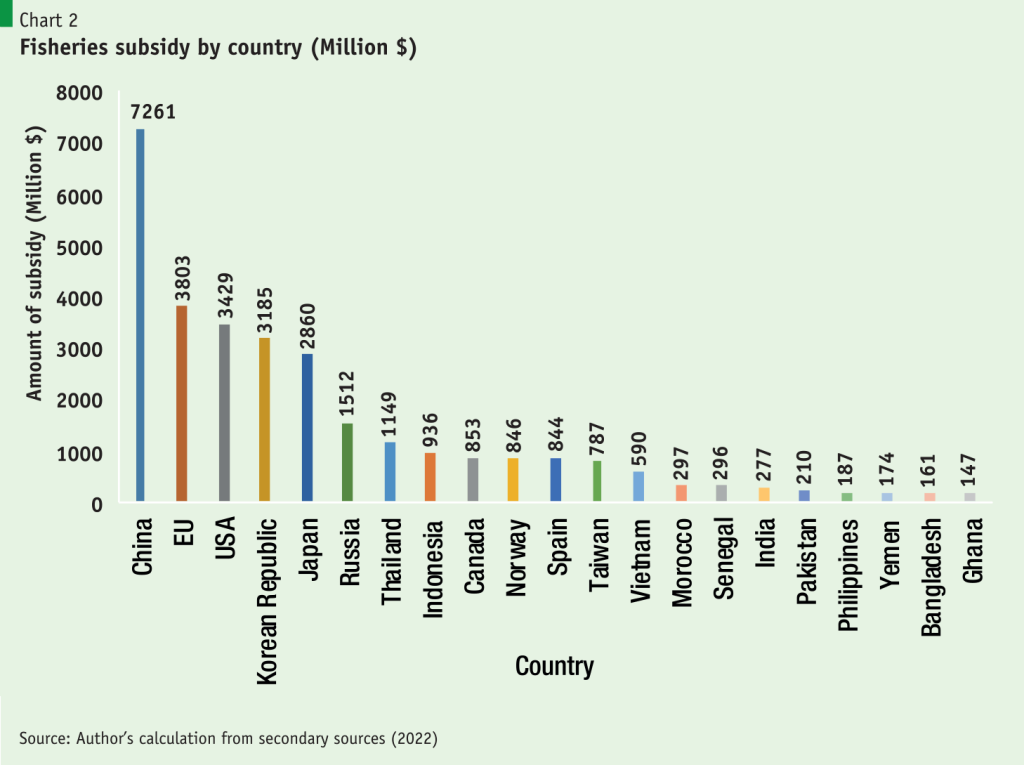

Marine Policy, is an international peer-reviewed leading journal in ocean policy that published several studies on fisheries subsidies from which the author showed top-producing countries have allegedly reached their level by enjoying subsidies (see Chart 2) on fuel cost, vessel construction, illegal and unregulated vessels, and price support to keep market prices artificially high.

On the other hand, insufficient subsidies in Bangladesh are not capable to purchase modern technologies (i.e. modern fleets, boats, and trawlers) that can sustainably harvest a lot from the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and high sea. It is evident from Chart 2 that the government of Bangladesh provides no special assistance to the sector (which provides only 161 million dollars).

In Bangladesh, the only tangible incentive provided to the sector is a value-added tax refund from fuel at a rate of 15% per liter or USD 0.04, following fish export (based on 1998 diesel prices of BDT 12.67 per liter). The sector benefits from general export-industry incentives such as duty-free imports of capital machinery and raw materials, fiscal incentives for export, income tax rebates, expedited customs clearance, and subsidized credit.

The WTO Agreement puts an embargo on some harmful fisheries subsidies such as illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU), fishing or fishing-related activities involving an overfished stock, and fishing in high seas that will undoubtedly decline the more subsidized country’s production tremendously. As a result, they will not be capable to meet the demand for fish and fishery products from the importer. Whereas, under the S&DT provision of WTO, Bangladesh will be able to continue subsidies up to 200 nautical miles for the next two years under an EEZ.

In these circumstances, this opportunity should be seized by Bangladesh, particularly in the case of industrial fishing (large-scale commercial fishing). Because Bangladesh is far behind in industrial fishing (17% of total marine production) than artisanal (small-scale traditional fishing) fishing (83% of total marine production).

That is to say, there is a huge scope to explore largely industrial fishing in Bangladesh. More fish could be harvested sustainably if the Bangladesh government provides more subsidies on fuel costs, boats, and fleets that are capable of fishing from the EEZ and high seas, as in other countries. With this, Bangladesh can harvest the fish species like Rup Chanda, Kolombo/Moricha, and White Poa which are not presently being depleted/overfished from the territorial areas.

More fish could be harvested sustainably if the Bangladesh government provides more subsidies on fuel costs, boats, and fleets that are capable of fishing from the EEZ and high seas, as in other countries.

If we can do it, the contribution of marine fisheries will be enhanced in the country’s total production and the total world’s production as well. No doubt, Bangladesh will be capable of earning more foreign currency than present (earns USD 405.21 million) by exporting quality fish and fishery products (frozen fish, frozen shrimp, chilled fish, dried fish and salted fish) as the requirement of the importers, particularly in the EU markets (It is better to say that here, unfortunately, no direct estimate of the country’s sectoral fish export is readily available. But, the lion portion of harvested marine fish is exported as the people of Bangladesh prefer to consume less marine fish).

But the concern is that subsidies could be given only for two years as a special and differential treatment for Bangladesh’s marine fisheries. Therefore, something different, such as non-subsidized measures (e.g. low-cost loans, duty-free import of marine fishing trawlers and etc.) needs to be encouraged to catch more fish in a sustainable manner (i.e. by keeping favourable environment for a higher reproduction rate of fish) from high seas and Exclusive Economic Zones in order to increase supply in the global fish market.

Acknowledgement: The author is expressing his gratitude to Dr. Zaidi Sattar, Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI) for his proper and immense guidance.